Walkabout: Calvert Vaux, Architect, Part 3

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 4 of this story. In 1859, a commission was formed by the New York State Legislature, charged with finding locations for parks in the rapidly expanding city of Brooklyn. James S. T. Stranahan, a wealthy Brooklyn businessman, was president of this Brooklyn Board of Park Commissioners. Washington Park,…

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 4 of this story.

In 1859, a commission was formed by the New York State Legislature, charged with finding locations for parks in the rapidly expanding city of Brooklyn. James S. T. Stranahan, a wealthy Brooklyn businessman, was president of this Brooklyn Board of Park Commissioners.

Washington Park, in Fort Greene, was the city’s first park, but the city needed more. They wanted the equivalent of Central Park, the enormous greensward which had just been completed across the river in Manhattan. The commission wanted something big, and after looking at six different locations, they thought they had just the place for it.

The glacier that cut through Long Island millennia before had left a terminal moraine that sliced through central Brooklyn, creating its highest points. One of them was Mount Prospect, the site of the city’s main reservoir and its water supply.

Nearby was Battle Pass, the site of the Battle of Brooklyn, during the Revolutionary War. What a great place for a park for the people, a landscaped reserve that would protect and celebrate these important locations. The park would also protect the reservoir from being surrounded by too much development.

The eastern portion of the park, surrounding Battle Pass, would be perfect for attracting wealthy people to a new upscale neighborhood that could be built for them. It was perfect.

Stranahan and his commissioners went to the engineer/designer who had crafted the original plans for Central Park, Egbert Viele. Mr. Viele had been replaced by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in Central Park, and he was eager to gain some respect and credit in his design for Prospect Park.

In 1860, he presented them with a plan for Prospect Park which included the Mount Prospect Reservoir, as well as Battle Pass in its footprint. Flatbush Avenue cut through the center of it, but that was an acceptable trade-off for including both sites. The plans were approved.

The City of Brooklyn began acquiring the land, through outright sale and eminent domain. Then the Civil War started, and everything was placed on hold until the war’s end. In 1865, the war was over, but those five years had given Stranahan some time to think about his park, and he wanted a second opinion.

Like just about everyone else, he greatly admired Central Park, so he turned to the men who had designed it, and invited Calvert Vaux to look over Viele’s plans for Prospect Park.

Vaux and his co-designer, Frederick Law Olmsted, were now quite famous for their brilliant design of Central Park. Olmsted was a well-known horticulturist and naturalist, and Vaux was also well-known in artistic circles as an architect and artist.

In 1857 he had published a very successful book of architectural designs called “Villas and Cottages,” which helped codify the Victorian Gothic architectural revival. Although Olmsted was of a front man for the park, Vaux had actually recruited him for the project, and was the more experienced man.

The story of their meeting, and Calvert Vaux’s early years and design influences can be found in Part One and Part Two of our tale.

Vaux looked over Viele’s plans and found room for improvement. He wanted to move the park to the west, so that Flatbush Avenue, a major thoroughfare, did not bisect the park. That cut out the Mount Prospect Reservoir.

He did want to have a considerable lake, and since the land they were considering had more than its share of swamp, he suggested moving the park’s boundaries into Flatbush at bit, to take advantage of natural springs.

The city had already bought the land in Viele’s plans, and Vaux wanted them to buy even more, including land owned by Edwin Litchfield.

The land on which Prospect Park would stand had already been laid out in a street grid. Litchfield, a wealthy real estate baron, owned much of what would become Park Slope and Prospect Park, a huge swath of land between his home, Litchfield Manor, built near 9th Avenue, (today’s Prospect Park West) down towards Gowanus, and ending at the piers at water’s edge in South Brooklyn.

Litchfield knew what he was sitting on, and if they wanted it, the city was going to have to pay. Vaux’s plans would totally upset the plans Viele had made, and would necessitate abandoning a great deal of the land already bought, and buying more. That was even before a single tree was planted. It was madness.

But Stranahan loved it, and convinced his commissioners that Vaux’s ideas were better, and worth the added time and expense. Poor Egbert Viele got booted out again.

Calvert Vaux contacted Frederick Law Olmsted, who had moved to California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains to work as manager of the Rancho Las Mariposas-Mariposa mining estate, and told him to come home. When Olmsted came back, he and Vaux went into a legal business partnership, and began working on the formal plans for Prospect Park.

In 1866, they presented their plans to Stranahan and his Parks Commissioners. The plans were presented in January, accepted in May, and work began on Prospect Park in June of 1866.

Work on the park commenced for over a year, and in 1867, it was opened to the public, even though it was nowhere near finished. They worked on it for another six years, until it was basically completed in 1873, although some of the original plans were never implemented.

The engineering and landscaping of Prospect Park was a monumental project. Like Central Park, nature would be molded to Olmsted and Vaux’s vision, and in the end, look as if it was always like that. One would think they had only to enclose it, and tweak it a bit. That was the nature of their genius. In reality, it was years of back breaking work.

The park has three sections; the meadow, the lake and the wooded ravine. They were not there before Olmsted and Vaux. They created these features, working with specific aesthetic and philosophical principals in mind. The Long Meadow brought to mind the pastoral scenes of England.

Pastoral landscape architecture was very popular in mid-19th century America, and had inspired the design of nearby Green-Wood Cemetery, which before Prospect Park, was the most popular park in Brooklyn. The meadow was created from the hilly landscape of peat bogs, pasture land and woods.

Trees were cleared from the site, and moved elsewhere or replanted singly or in groups around the meadow. Soil was brought in to level the field, and turf planted to create an English style landscape.

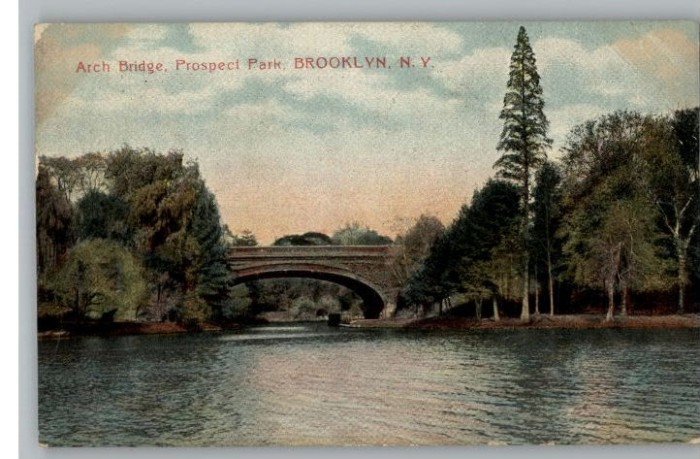

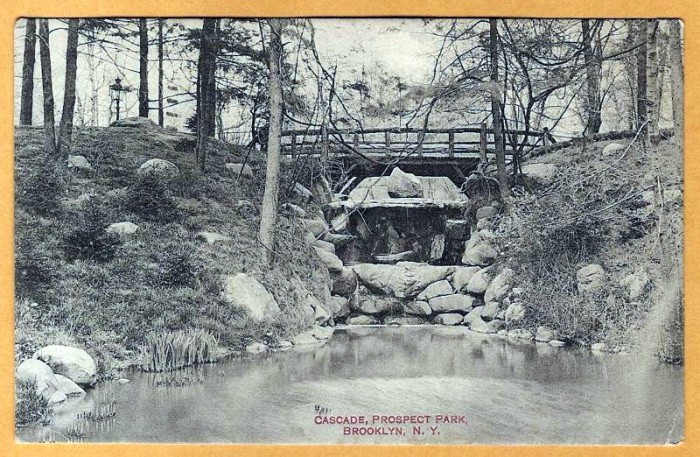

The watercourse was created to meander through the park, creating a sublime naturally beautiful scene, as if the park goer had been the first to gaze upon the water. Olmsted and Vaux took advantage of the natural ponds and swampy land in the park and created a grand watercourse.

All of it is man-made, and was all dug by hand by hundreds of workers, using early digging machines and thousands of hours of manual labor. The winding stream open up into a series of ponds, into the Lullwater, and finally down into Prospect Lake. It was gorgeous.

The crowning achievement of the park, from a naturalistic perspective, was the Ravine. It is the heart of the park, deep in its interior, and is Brooklyn’s only remaining natural forest.

Olmsted and Vaux saw the Ravine District as a steep, hilly landscape reminiscent of the Adirondack Mountains, with a running stream, deep woods, and hilly terrain. The Ravine is considered to be the masterpiece of the park, their greatest example of landscape architecture.

All along its pathways, trees and boulders were moved or arranged to best advantage, and here, as in all of the park, plants, trees and flowers were placed in the most naturalistic and visually appealing way, giving park goers what Olmstead believed was a “sub-conscious” experience of nature within a city, necessary for the nourishment of the urban soul.

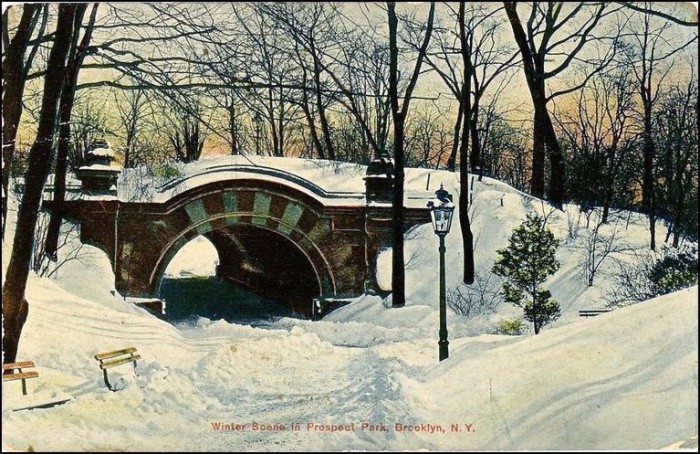

Vaux was the builder. His bridges, pathways and naturalistic buildings within the park were designed to enhance the natural elements, not overwhelm them. His pavilions, bandstands, and rest stops peek out from the trees, and were delightfully wrought in many different architectural styles.

Some were influenced by the Adirondack camps becoming popular upstate; others were fanciful excursions into Eastern and “Oriental” follies, capturing the fascinations of the Aesthetic Movement. His bridges and tunnels were genius, ushering park goers into his world.

As they emerged from these tunnels, the landscape spread out before them, like in a dream of heaven. Prospect Park was an utter and total success.

Next: Calvert Vaux did not sit on his laurels. Central Park had given them a reputation. Prospect Park secured their fame for the ages, and Olmsted and Vaux were wanted everywhere. Our story continues next time.

(Prospect Park Postcard, 1907)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment