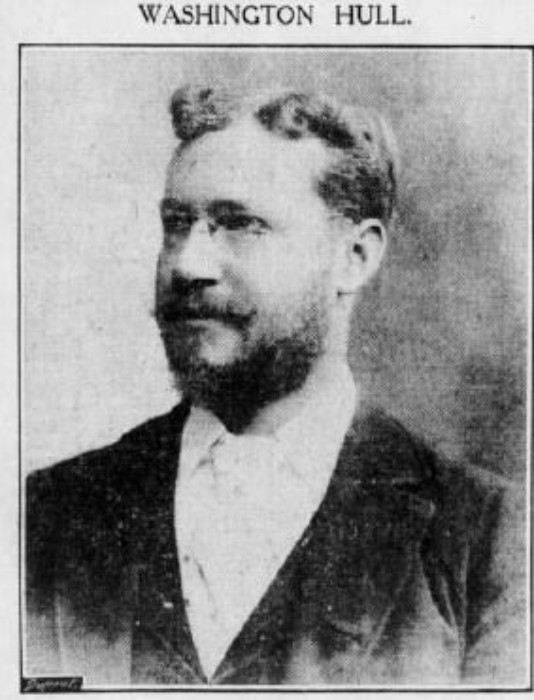

Walkabout: Washington Hull — Brooklyn’s Forgotten Architect, Part 3

Read Part 1, Part 2 and Part 4 of this story. In 1903, a young Brooklyn architect named Washington Hull won a competition to design the new Municipal Building for the borough of Brooklyn. His design was deemed the best, with competition from the Parfitt Brothers, William Tubby and other important Brooklyn architects. The Borough…

Read Part 1, Part 2 and Part 4 of this story.

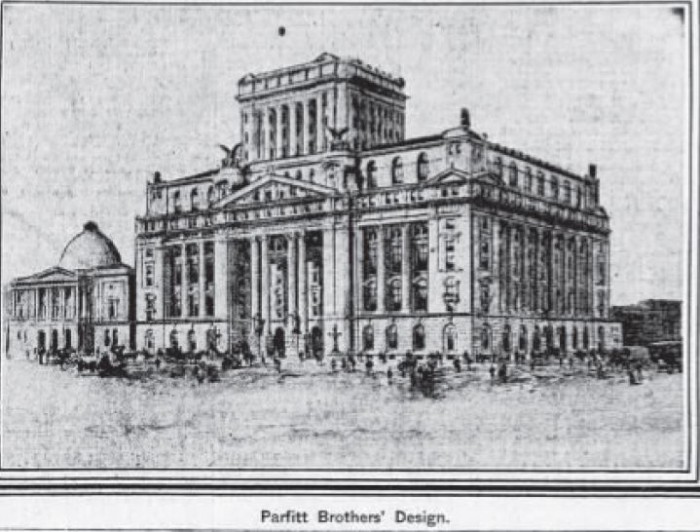

In 1903, a young Brooklyn architect named Washington Hull won a competition to design the new Municipal Building for the borough of Brooklyn. His design was deemed the best, with competition from the Parfitt Brothers, William Tubby and other important Brooklyn architects. The Borough President at the time, J. Edward Swanstrom, made the announcement at the end of November, 1903. Unfortunately, he had not been returned to office by the voters, and a month and a half later, Swanstrom was gone, and new Borough President Martin Littleton took over.

Littleton had great ambition, and a larger ego, and he immediately put out the notice that he would be reviewing everything that his predecessor had put into effect, and he would be making changes if things didn’t meet his exacting standards. One of those projects was the new Municipal Building. Three months after taking office, Littleton made the announcement that he didn’t like Hull’s design, and he wanted to void the prize and Hull’s signed contract and have a do-over.

Littleton held a press conference where he announced that he was going to get a better design. He owed it to the people of Brooklyn, he said. The story of this competition can be found in Part 2 of this story. Needless to say, this did not go over well with Washington Hull, who was left holding a lucrative contract that wasn’t worth the paper it was printed on.

Former Borough President Swanstrom was interviewed on the topic, and he was not happy with the decision either. He noted that Hull had won the competition fair and square, and that his design had been chosen by a judge with impeccable credentials. The sole judge, Professor Despredelle from M.I.T., was not even from New York, and therefore was not swayed by any local politics or other influences. The professor had chosen Hull’s design because of his functional and economical use of space within the building, as well as the beauty of the building’s façade.

The architectural community was also in an uproar. If a politician or city official could simply decide to not honor a contract, fairly negotiated and awarded, then this was a precedent that did not bode well for them in other projects all over the city. Both Swanstrom and the architectural community, as represented by the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects, wanted the award to stand. If Littleton had changes to the plans, or even demanded a new design, then he should have Mr. Hull execute those changes, and remain on the job. Littleton should not be allowed to simply toss the architect along with his winning design to the curb.

The project was stalled. Littleton told reporters that he had rejected Hull’s plans because he didn’t like the design very much, but mostly because Hull had misrepresented and miscalculated how much it would cost to build the new Muni Building. Hull responded that since time had gone by, some things may no longer have the prices he quoted, but he was more than willing to change his design in order to make the numbers work. Littleton had no intention of giving him the chance. As the project lay in limbo, Hull had other problems to worry about. The endless journey that was Senator William Clark’s mega-mansion in Manhattan was still going on.

As covered in Part 1 of the story, Hull and his former business partners, Lord & Hewlett, were still trying to finish what would end up being a 121-room mansion for one of the country’s richest men, copper mining tycoon William A. Clark. The project had brought out some serious acrimony between Hull and Hewlett, and the disagreements had landed in court. On the face of it, the relationship between the former partners was like a bad marriage.

The offices of Lord, Hewlett & Hull were at 14 East 23rd Street, in Manhattan. Since the breakup, they had split the space, with “Lord & Hewlett” on one door of one part of the office and “Washington Hull” on the door of the other. They had different clients, were fierce competitors for jobs, and the only thing keeping them together in the same space was the Clark job, which they were contractually obligated to both do. Besides which, neither one of them was going to give up the big bucks Clark was paying them to the other.

They ended up in court. But not for what one might think. A third party, Kenneth Murcherson, was a draughtsman for the project, working for the firm of Lord, Hewlett & Hull. Mercherson’s daughter was a friend of William Clark’s daughter, and allegedly, Lord, Hewlett & Hull got the job on the mansion because of that connection. In return, LH&H had agreed to pay Mercherson 10 percent of their commission to him as a finder’s fee.

This went against the story that Clark had given them the job because of their winning the contest to design his mausoleum in Woodlawn Cemetery. Hull refused to pay his share of the fee to Mercherson, but the other two men obliged. The court case arose out of Lord and Hewlett attempting to get Hull to pay up. In the process of discovery it was learned that the plans finally approved by Clark for both the mausoleum and Clark’s mansion were drafted by a French architect named M.H. Deglane. The Americans had tweaked the plans, changed them as Clark ordered, made local code other changes, and then carried them out. Mercherson had been hired specifically to draft the changes and alterations.

Hull had been project manager for Clark, and had gone above and beyond in getting the project done. It was he who secured the land next door to Clark when the tycoon had decided his art gallery wasn’t big enough. Hull had not only arranged the purchase, he had to have the two mansions on that property razed so the Clark house could be expanded. He personally had also arranged for Clark to buy a limestone quarry and a bronze company to produce materials for the enormous mansion when Clark balked at the prices other outside vendors were charging.

So what that Mercherson had drawn up some plans? That was what he was hired to do, and was on salary for. Hull did not think he should get ten percent, especially considering the amount of work Hull had put into the project, work that went well above what any supervising architect had ever had to do. It was a matter of principle. If Lord & Hewlett wanted to pay him 10 percent of their take, that was their decision. He wasn’t going to. Besides, they were no longer partners.

The courts didn’t agree, and sided with Lord & Hewlett, forcing Hull to pay his share of the 10 percent. Hull appealed, and the Appellate Court reversed the decision. It allowed for the dissolution of the firm of Lord, Hewlett & Hull and made Kenneth Mercherson pay Hull the third of the commission that had he had previously been awarded. Hull was pleased. It was one of the few pleasures he had, since the mess with the Municipal Building in Brooklyn was not going his way.

By 1905, Borough President Littleton had made his decision. He did not hold a new contest, and he did not allow Hull to modify or change his winning design. There had been early talk of combining the Hull plan with elements of other top rated designs from the contest. Hull had been amenable to that, anything to avoid losing this prestigious and lucrative job. But Littleton just wanted him and his plan gone. In 1905, he announced that he was going to give the contract for the Municipal Building to the most famous firm of architects in the country – McKim, Mead & White. They had drawn up plans, and would be building Brooklyn’s new Municipal Building. They were also Washington Hull’s old bosses.

But fate intervened. Littleton was not re-elected. His successor, Bird S. Coler, won the November 1905 election. When he came into office on New Year’s Day, in 1906, Coler was not obligated to carry out Littleton’s plans any more that Littleton felt he was obligated to respect Swanstrom’s plans. Needless to say, Coler decided he didn’t like the McKim, Mead & White plans, and tossed them into the wastebasket too. Brooklyn was not going to get a new Municipal Building anytime soon.

He lived rather modestly in Fort Greene, with his wife and children, and enjoyed club membership and the other perks of an upscale lifestyle, including a summer home on Long Island. His wife was a well-loved Brooklyn’s Society Lady, and was a gifted pianist and musician. She was involved in many charitable and social events in Brooklyn, especially revolving around music. Hull had his own hobbies and loves. One of them was yachting. He owned a sloop, which he took out whenever he could. The sea gave him peace, something his career and relationships with colleagues and clients did not.

In 1909, while still working on the Clark mansion, as well as other projects, Hull’s life came to an abrupt end. His death was a tragedy and a great mystery. Read on in Part 4 of this story.

Read Part 1, Part 2 and Part 4 of this story.

Top photo: Sketch of Parfitt Brothers’ design for the new Municipal Building. I love the Parfitts, but no wonder they did not win. Yeesh. Photo via Brooklyn Eagle, 1910

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment