Walkabout: The German American Stores Fire in Red Hook, Conclusion

By Suzanne Spellen (aka Montrose Morris) Read Part 1 of this story here. The afternoon of October 24, 1898, started out as usual on Pier 39 in Red Hook. This was home to the German American Mutual Warehousing and Security Company, aka the German American Stores. They operated one of Red Hook’s larger storage and…

By Suzanne Spellen (aka Montrose Morris)

Read Part 1 of this story here.

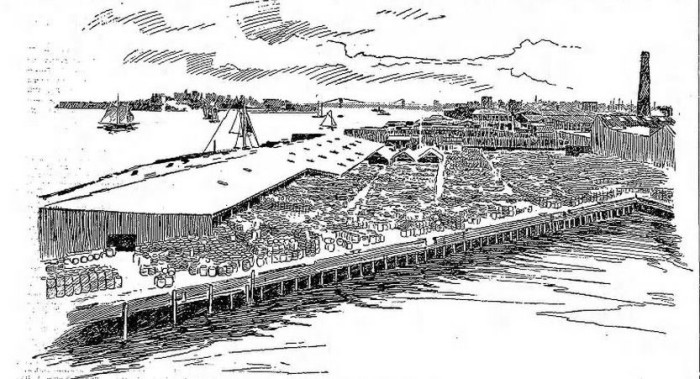

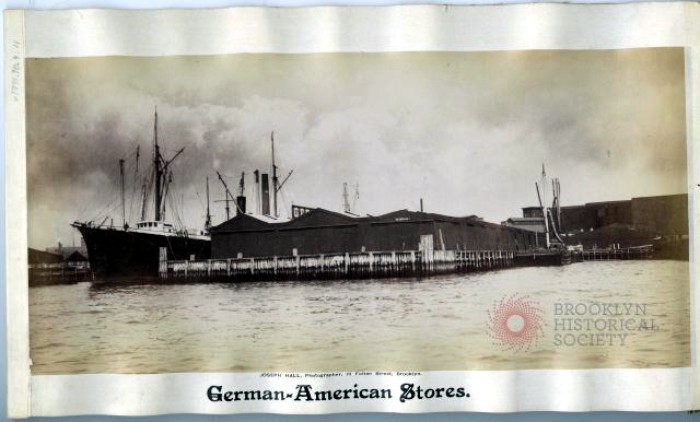

The afternoon of October 24, 1898, started out as usual on Pier 39 in Red Hook. This was home to the German American Mutual Warehousing and Security Company, aka the German American Stores. They operated one of Red Hook’s larger storage and warehousing facilities; receiving, storing and shipping goods from all over the world.

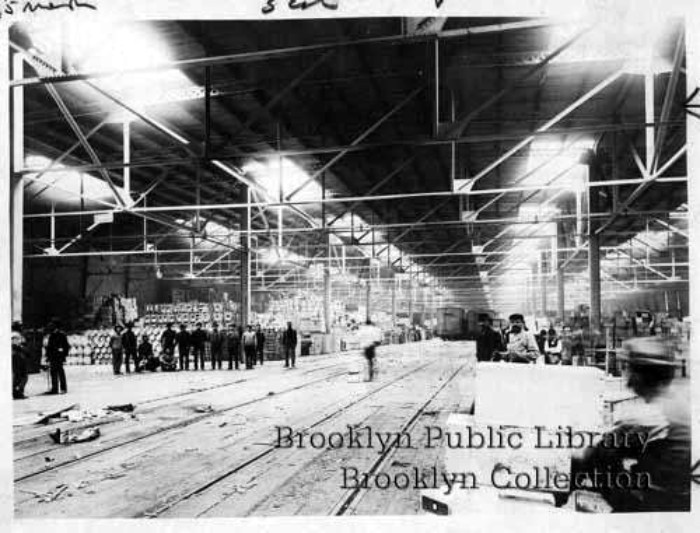

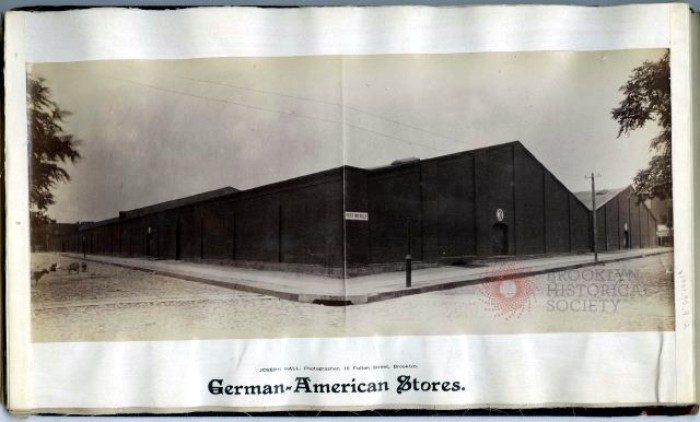

They were one of Brooklyn’s largest cotton warehouses, and also stored vast quantities of jute, silk, sugar, and other commodities. Their vast storage space included brick warehouses, covered sheds, and two long piers with covered storage buildings running the length of the piers.

Like all of Red Hook’s warehouses and factories, they stored extremely flammable goods right next to equally flammable accelerants. Apparently there were no laws preventing such practices at the time. All of the dusty plant matter stored also caused spontaneous combustion. Consequently, fire was not uncommon along Brooklyn’s shoreline and in her adjacent factories.

Because the threat of fire was so great, the local fire houses were staffed with a lot of men and equipment. Over the years, a fleet of fire boats had also been established to fight fires from the water. They would need them all this day.

The details leading up to the fire can be found in Part One. A British sailing vessel named the Andorinha had been moored at Pier 39 for two weeks. They had sailed from Calcutta with the holds bursting with thousands of bales of jute, as well as silk, shellac and tons of potassium nitrate, more commonly known as saltpeter. This substance was extremely flammable, and is a component of fertilizer and gunpowder.

The boat was being off-loaded by two smaller vessels called lighters, open sailboats that acted as water bound pickup trucks. They delivered the bales and barrels to the pier, where the stevedores stacked them on the pier. On that day, Pier 39 was loaded with jute as well as bales of cotton from another ship.

The fire probably started on the Andorinha, around 3:15 in the afternoon. A spark came from somewhere. The dusty dry jute exploded into flame, and quickly spread from the ship to the lighters and onto the pier. It was so fast, and burned so hot, that efforts to put it out failed, and many of the sailors had to jump overboard to escape the heat and flames.

The wind picked up in anticipation of disaster, and in ten minutes the fire was raging through the jute and cotton on the pier. The loosely packed burning jute and cotton sent puffballs of fire into the air which travelled to both sides of Pier 39 and set Piers 38 and 40 on fire as well.

The fire alarm quickly went out, and went out again and again. The fire was a four alarmer in the space of ten minutes. The call also went out to the fireboats, which raced to the scene from the Fulton Ferry station and from other locations in Manhattan.

The jute and cotton were burning fiercely, setting the dock below on fire. The fire was threatening to move inland to the German American Stores’ other buildings, mostly filled with bales of cotton. Over on pier 38, the fire was consuming the pier itself. Thick black smoke began to rise, making it difficult to see.

Pier 40 was the home of the Union Naval Stores. Their dock was huge, with loading space and large covered sheds on the pier itself sheltering thousands of barrels of flammable resin, turpentine and benzene. Moored to her dock was a ship just arriving from North Carolina called the Wacamore. She was full of even more of the same substances.

The arriving fire chief was quickly apprised of the situation. He had only minutes to act before the barrels on Pier 40 began exploding, or the Andorinha blew up in a massive saltpeter-fueled inferno. As he assessed his options, a few isolated barrels of benzene on Pier 40 began to blow.

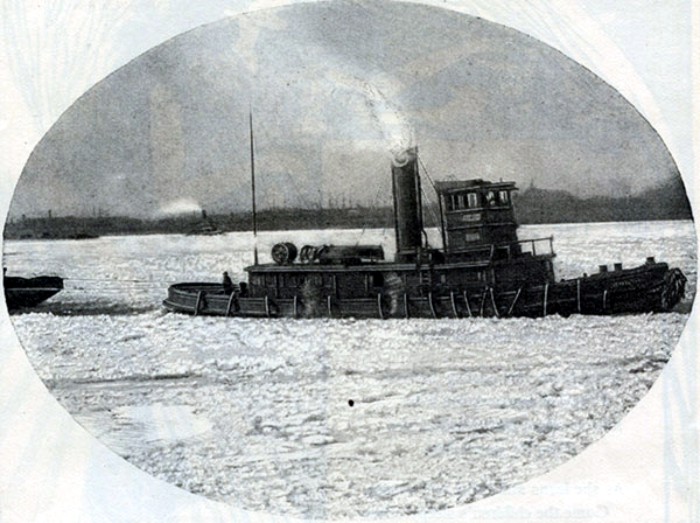

As the fire grew, about ten tugboats in the bay converged on the site, drawn to help and to salvage, if possible. They proved invaluable.

Quick thinking saved the Wacamore. Tugs pulled the schooner pulled away from the dock into the bay, where the crew was able to put out the small fires and stop any explosions. She suffered only minor damage.

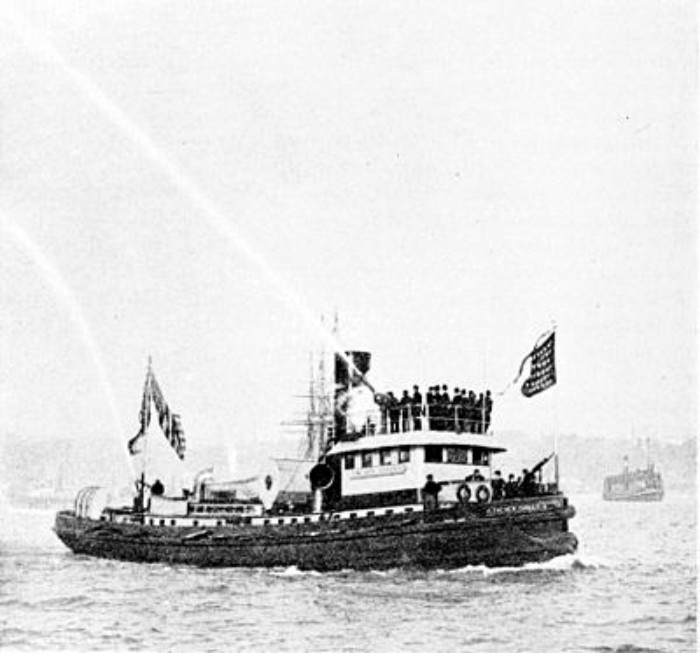

The fireboats approached the scene. Somehow, the Andorinha was loosed from her moorings, and towed by tugs out into the Erie Basin. As she was towed, her sides, deck and rigging blazed with fire. As the vessel continued to burn, the fireboat Zophar Mills took control and directed tons of water onto the barque.

It took a half hour of furious firefighting, but at last the Andorinha’s fire was mostly out, and the threat of exploding saltpeter was neutralized. She was towed to the head of the Gowanus channel and beached far from anything flammable. But back on shore, things were taking much longer.

The flames on the piers shot 200 feet into the air, burning hot and furiously as the cotton, jute and wooden structures fueled the flames. Battalion Chief James Doyle sent out more alarms, as the fire continued to spread. Men from 16 engine companies joined the fight. The Deputy Chief of the entire department, Chief Dale arrived, and took control.

As the firemen poured water on the flames on Pier 39, the barrels of benzene stored on Pier 40 continued to explode. The turpentine and resin followed. Thick black smoke rose from the new fires, making it next to impossible for the firemen to see. 1898 was long before protective gear or oxygen tanks. Men were blinded by the heat and smoke, while others vomited. They had to pull back.

Out on the water, the fireboat Zophar Mills was joined by the Seth Low, David A. Boody, Robert Van Wyck, Havemeyer and the New Yorker. The Seth Low and David Boody were from Brooklyn, the others from Manhattan. They attacked the fire from the water, spraying seawater on the docks and buildings on the piers.

They also had to contend with burning resin. Barrels of the stuff had exploded on Pier 40. Some of it accelerated the fires on land, but a great many of the barrels had been launched off the piers by the explosions, or had been thrown off the Wacamore, and had caught fire on the water.

The burning resin floated on top of the water, clung to debris, or threatened to stick to the fireboats, setting them on fire. The boats tried to avoid the burning stuff, but were hampered from getting as close to shore as possible, due to the flaming water. They did what they could, but had to wait until after dark to get in close, as the resin and other flammables burned themselves out.

The fire department decided to let Pier 39 burn. After about an hour, the floorboards and supports of the wooden pier burned through and collapsed. What was left of the burning jute and cotton fell into the water and drowned. Also destroyed were two large wooden hoists used in transporting goods from ship to shore.

They did not want the larger German American warehouses behind the pier to burn. One was filled was filled to the rafters with cotton, the other, a brick building, was full of jute. A contingent of firemen and two of the fireboats directed their hoses on these buildings, and after several close calls, were able to prevent them from catching fire.

The fire burned for over six hours. The thick black cloud that rose from the scene traveled northward across lower Manhattan and northern Brooklyn. At times, it was so dark that people thought a storm was coming. Offices and homes in the area had to turn on their lights in the afternoon. No one had ever seen anything like it before.

Across Brooklyn Heights and along the water, people gathered on the roofs of buildings to watch the fire. People took the Staten Island Ferry just to see the fire as they passed. Men and women could be seen standing on shore and on buildings on Governor’s Island, in Lower Manhattan and even on the Brooklyn Bridge.

Curious gawkers, tourists and opportunists headed for the scene. Fortunately over six precincts had turned out, with over 80 men, most of whom ended up in crowd control, keeping the spectators away from danger and trouble.

In addition to the main fires, many smaller ones burned. One was in an empty lot used by Union Navy Stores as storage for resin. The 100 barrels there were far away from everything else. When they caught fire, they were allowed to just burn. Other small fires were identified and put out.

Firemen saved the wooden Ligerwood Iron Manufacturing Company building, a block from the shore. The fire ended up spreading in various ways and places, about one block in from the water, and across the space of three or four blocks across. Considering, they got off easy.

After the fires were put out, the next morning the damages were accessed. There were conflicting accounts as to where the fire started. The witnesses and the newspapers were split 50-50 between Pier 39 or aboard the Andorinha. In any case, it was deemed to be spontaneous combustion, and no one was arrested or charged. Spontaneous combustion was an all too familiar fire hazard in the stores.

Pier 39, Pier 38, the two lighters, and the Andorinha were toast. Pier 40 was heavily damaged, and 30,000 barrels of turpentine, benzene and rosin had been destroyed by the fire. The owners of the cotton and jute shipments were out a thousand bales of each, but both had much, much more saved by the firemen and boats.

The Wacamore had a burned deck and rigging, but was not seriously damaged. A $25,000 pile driver, which had been on one of the piers was also destroyed. All in all, it was estimated that about $680,000 worth of damage had been done. In today’s money, that would be around $19 million.

Miraculously, no one; not the sailors, dockworkers, firefighters or anyone else was seriously hurt. All of the companies involved were insured, and recouped their losses. They all rebuilt and carried on business as usual. In the years to follow, German American Stores began subdividing their large warehouses and installing fire walls to insure that any future fires would not be able to spread easily.

A few weeks after the fire, the Andorinha was salvaged from where she had been beached, and was pumped out and taken away. The once handsome 4-masted barque had been sold, and was to be stripped down and converted into a barge. She was, in a way, the most tragic loss of this fire.

Top picture:Interior of one of German American Store’s covered piers. Brooklyn Public Library

This article was sourced from the Brooklyn Eagle, New York Times, Brooklyn Standard Union, NY Sun and the New York Tribune. Many of the period drawings and photographs, as well as other background information came from that invaluable Red Hook family journal compiled by Ms. Maggie Land Blanck. Her blog maggieblanck.com is a Red Hook and South Brooklyn bible.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment