Past and Present: The Brooklyn Eagle Building, Housing the Eyes and Ears of the City

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. The Brooklyn Eagle newspaper began as the paper of record for a growing city, and was at its finest as the city grew into a great metropolis. The paper reported about Brooklyn life, events and people continuously for 114 years. The Eagle began back in 1841 as the…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

The Brooklyn Eagle newspaper began as the paper of record for a growing city, and was at its finest as the city grew into a great metropolis. The paper reported about Brooklyn life, events and people continuously for 114 years.

The Eagle began back in 1841 as the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and Kings County Democrat. Its owners were Isaac Van Anden and Henry Cruse Murphy. The two men had originally planned to publish the paper as a morning paper, which along with news, would be an arm of Democratic Party politics.

In 1842, Henry Cruse Murphy became Mayor of Brooklyn. The paper continued to grow, covering not just local news, but extending its range to international and national news as well. That was rare for most morning dailies.

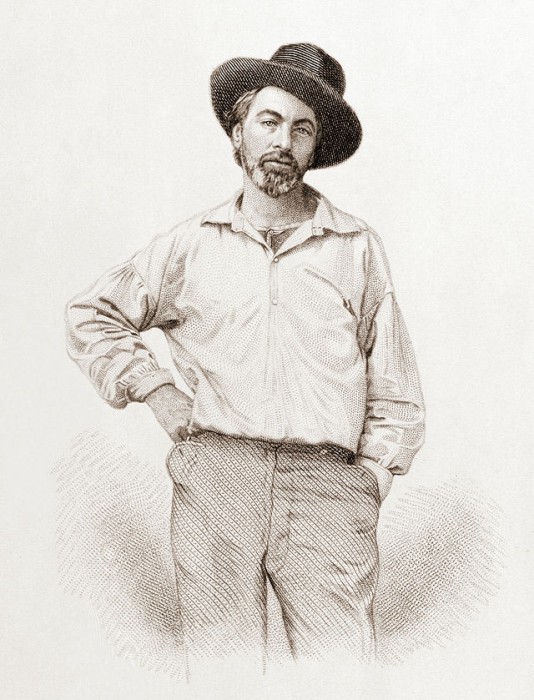

The editor of the Eagle between 1846 and 1848 was poet Walt Whitman. Whitman was a printer by trade, in addition to being a writer and poet, and had worked for several different newspapers in NY and Long Island before coming to the Eagle.

He only lasted two years at the paper because he fell out with Isaac Van Anden. Whitman was a supporter of the “Free-Soil Movement” wing of the Democratic Party, and Van Anden was a strong supporter of their opposition, the more conservative wing of the party.

Crossing one’s boss over politics is never a good idea, and Whitman was encouraged to move on. During the Civil War, the paper continued to support the Democratic Party, quite a stand in what would be a very Republican city in later years. That would later change, as the times changed.

The paper’s glory years were really the years between the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883 and the consolidation of Brooklyn with the rest of New York City in 1898. During that time, Brooklyn took its place as one of the most important and prosperous cities in the country.

The Eagle was there with the news of the day, but also was the city’s publicity arm. They printed a yearly almanac which touted the greatness of the city, its organizations and people. They also printed several series of picture postcards featuring the great buildings of the city, everything from governmental buildings to schools, banks, houses of worship, mansions and charitable institutions.

As the paper approached the 20th century, it was the most read afternoon paper in the country. With its big city boosterism, small town and neighborhood gossip, as well as national and international news, the paper had something for almost everyone.

Up until the 1890s, the paper’s offices and publishing presses had been in a building at 26 Fulton Street, down near Fulton Landing. They had been growing tremendously since the Civil War, adding more and more presses, and had reached the building’s capacity. They needed a new headquarters.

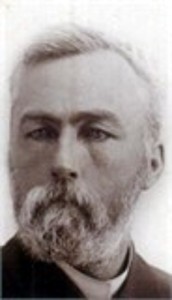

By 1890, George L. Morse was one of Brooklyn’s most respected and successful architects. He was responsible for civic and private buildings throughout the city, with churches, commercial buildings, houses and apartment buildings, throughout the city. His most important contributions were still yet to come.

He was also the president of the Architectural Department of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, which today is the Brooklyn Museum. The Institute back then was not only a museum, but a university-like setting, with various departments in the arts and sciences teaching and mentoring students. Mr. Morse was a highly respected man.

That made him perfect as the designer of a new Brooklyn Eagle building. Brooklyn’s civic and business center had moved up from the harbor, and was now centered on Fulton and Court Streets, so that’s where the paper of record wanted to be.

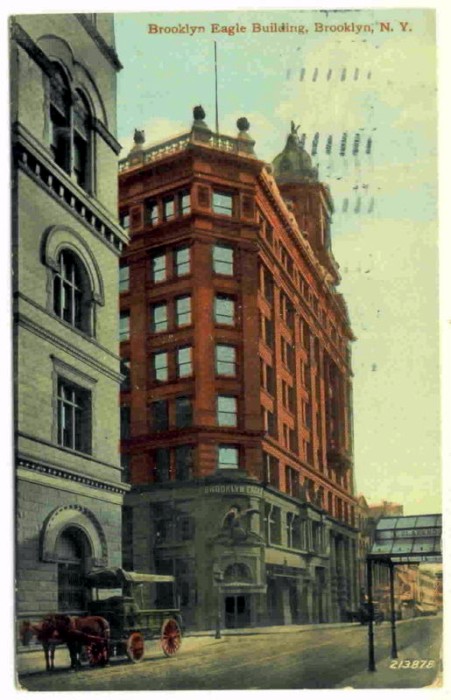

The land they bought was home to the Brooklyn Theater, which had its last performance on June 2, 1890. The theater was torn down, and the new Brooklyn Eagle building soon rose on the site, at the corner of Johnson and Washington Streets. The eight story building, plus tower, was finished in 1892.

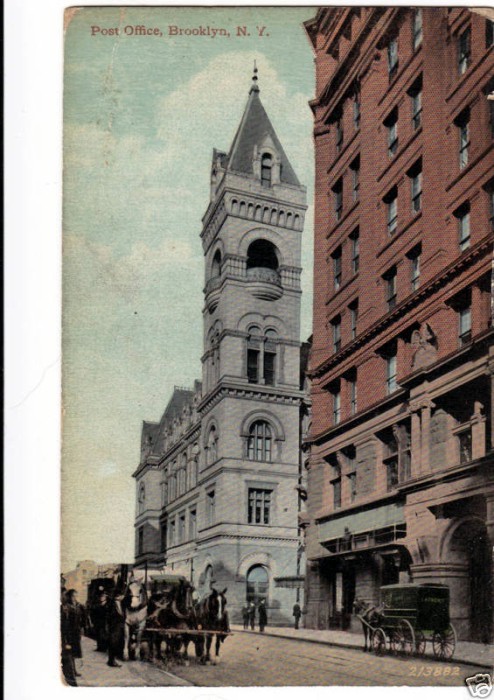

The Eagle building was just across the street from Brooklyn’s grand and gleaming new General Post Office. The two buildings would often appear together in post cards and photographs, both examples of the grand civic pride of Brooklyn.

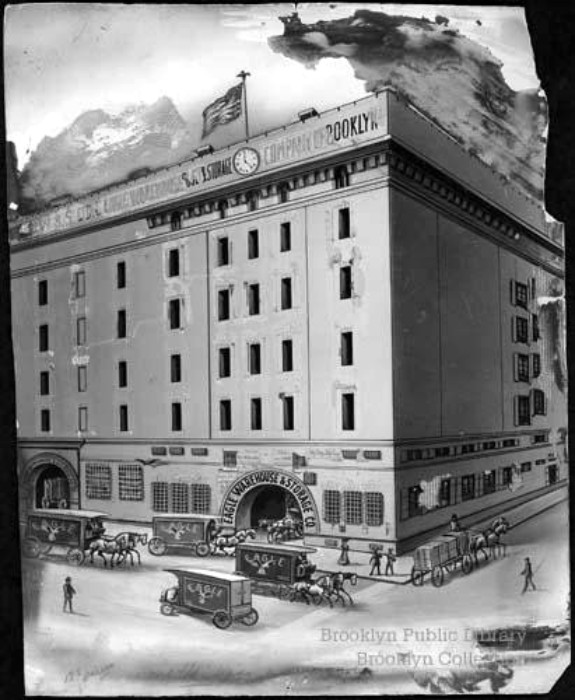

The space abandoned by the Eagle on Fulton Street became the site of the Eagle Warehouse and Storage building, architect Frank Freeman’s most famous building. The warehouse was named in honor of the paper’s long history at the site.

Back at the new Eagle offices, the paper continued to grow, but it didn’t occupy the entire building. The Eagle presses and offices only took up part of the building, the rest was office space. George L. Morse established his own offices here. What better advertising for an architect?

The Brooklyn Eagle initially was not in favor of the consolidation of the city, “the Great Mistake,” as many would call it. They hated Tammany Hall, which ruled Manhattan. They also knew that once Brooklyn became a borough, much of the greatness of the independent city would be phased out. Brooklyn would lose its autonomy. It could have lost its paper, too.

But it adapted, merged with other Brooklyn dailies, and remained a vital part of Brooklyn life. It never tried to be a tabloid for the entire city. It remained Brooklyn-centric for the rest of its run.

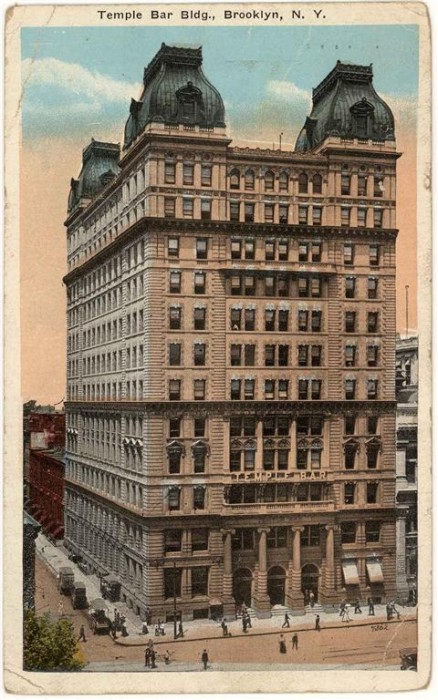

After the Eagle building, George Morse went on to design some of his greatest accomplishments, such as the Franklin Trust Building on Montague Street, the Temple Bar Building on Court Street and the Old First Church in Park Slope, among others.

The Brooklyn Eagle changed over the years, modernizing as all papers did, adding photographs, larger print, and different layouts over the years. They provided essential coverage of both world wars, especially World War II. So many of Brooklyn’s young men were overseas; so many died and were wounded. The Eagle was the only paper interested in their stories and the stories of their families.

The paper was far from perfect, and reflected the good and bad of American society throughout its entire run. Minorities, non-English speaking immigrants and the poor were never their favorites, although sometimes there were brilliant bursts of understanding and positive coverage.

But by 1955, the paper was in trouble. A protracted American Newspaper Guild strike was its death blow, after the owner had been searching for a buyer anyway. That was it. The last edition of the paper was printed on January 28, 1955. A public sale of all of the Eagle’s assets followed.

That fall, the Dodgers won the World Series of 1955. The Eagle would have loved that. But two years later, they would have had to report that the team was leaving town. Many people remarked that they were glad the paper had died before having to print that headline. Today’s Brooklyn Eagle publication has no relation to the original newspaper.

The paper’s archives and morgue were donated to the Brooklyn Public Library in 1957. This included clippings, photographs and negatives and other archival information. The entire run of the paper, from 1841 to 1955 has now been digitized and is available on line. Photographs from the paper’s vast collection are available on line from the library’s Brooklyn Collection.

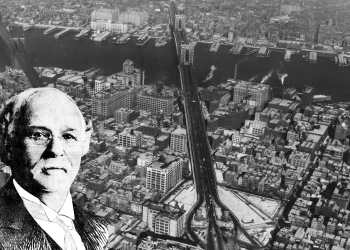

Even as the paper was going out of business, plans were in the offing to create a vast new civic plaza with a new Supreme Court building. Since the Eagle building was no longer home to the paper, it was on the chopping block along with all of the other buildings crowded into the area now known as Cadman Plaza.

Robert Moses and his team tore down all of the buildings on Washington Street, south of the Post Office. Washington Street became Cadman Plaza East. The Eagle building site is now part of the 1957 New York State Supreme Court Building, designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon; the architects of the Empire State Building.

It is gone, but not forgotten. The zinc eagles that once stood guard above the entrances are now permanently ensconced in the main branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, at Grand Army Plaza, home of the Brooklyn Collection and the Eagle’s morgue. Those eagles still guard Brooklyn’s greatest newspaper.

i nearly shed a tear of brooklyn pride!