Architect Benjamin Driesler and the Building of Brooklyn

Benjamin Driesler was a busy man, designing hundreds of homes in Flatbush and Long Island, while also contributing to the architectural landscape of brownstone Brooklyn.

Photos by Susan De Vries

Editor’s note: This story is an update of one that ran in 2013. Read the original here.

Quite a few of Brooklyn’s most prolific and successful architects have a German background: the Berlenbachs, father and son; Rudolph Daus; William Schickel; and the most prolific of all, Theobald Engelhardt. To this list, we can add another: Benjamin Driesler. His work appears mostly in Flatbush and Long Island, and he was a busy man, designing hundreds of homes in those areas while also contributing to the architectural landscape of brownstone Brooklyn. He also was quite active in Brooklyn’s architectural enclaves, leading architectural organizations, and contributing to the general public’s knowledge of just what it was an architect did. This is his story.

Benjamin Driesler came from Bavaria, and was born there around 1867. He came to the United States in 1881. We don’t really know what he was up to until 1895, when his name appeared as a builder, with an office in Flatbush, on Avenue C and Flatbush Avenue. By 1896, his name starts appearing as an architect in the Real Estate Record and Builder’s Guide, which tracked the building trades in the New York City metropolitan area.

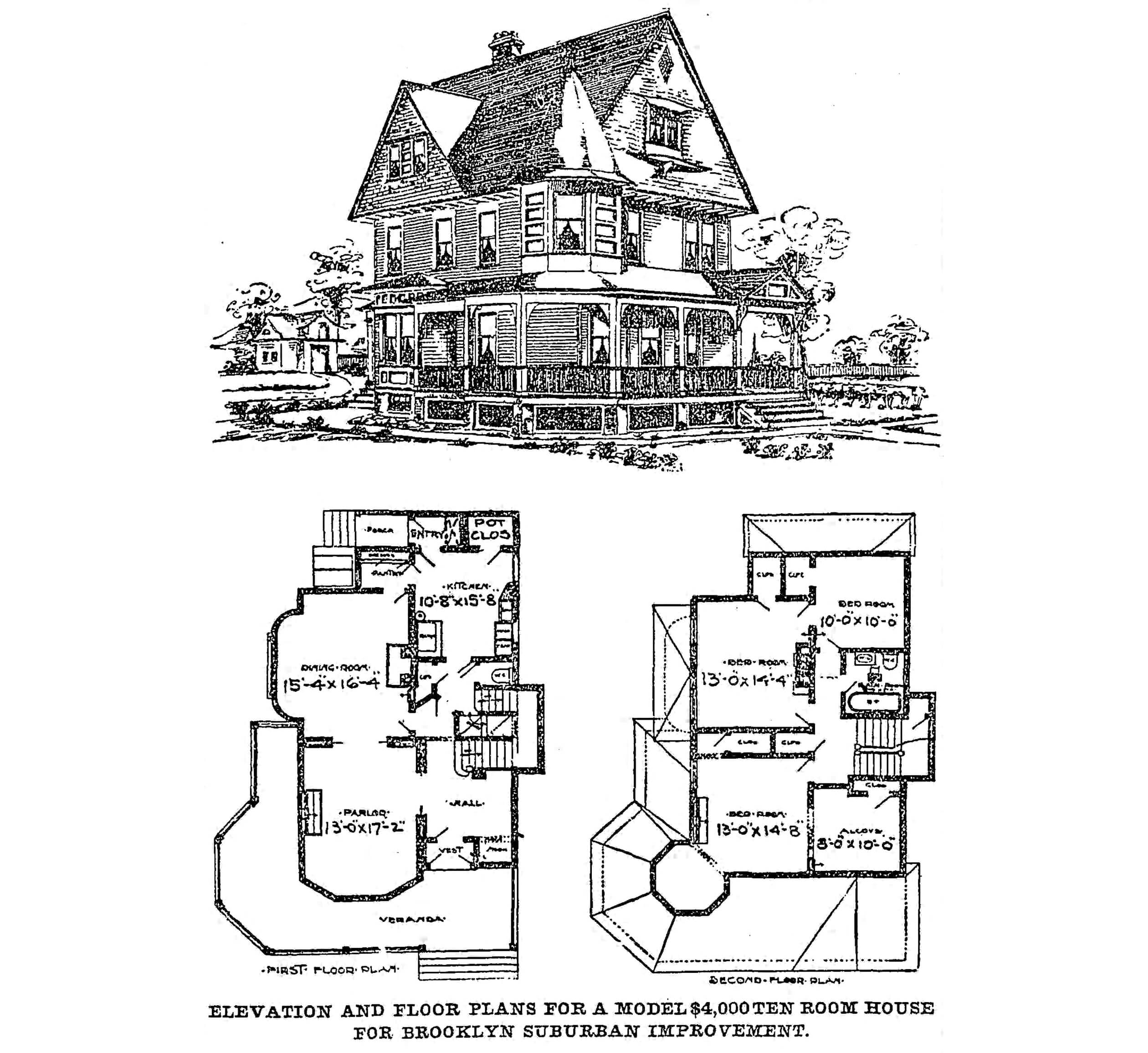

A great deal of Driesler’s work was in Flatbush. Between 1899 and 1911 he designed 16 homes in Dean Alvord’s Prospect Park South. His homes also appear in other parts of what we call Victorian Flatbush. In Midwood South alone, he designed 20 frame cottages, all typical of his suburban-style middle-class housing work. In a newspaper advertisement, he wrote that he had designed more than 400 such cottages across Flatbush, Long Island and New Jersey, all modest and modern suburban homes, reasonable in cost. A group of 10 homes in Kensington was described as being for “clerks and other skilled workmen.”

The book “Flatbush of To-Day,” published in 1908, lists Driesler as one of Flatbush’s leading citizens. The author says that Driesler called Vanderveer Park his home, a neighborhood that no longer exists today. The architect claimed to have a folder of almost 4,000 buildings that he had designed and built over the years, of which he said over a third were in Flatbush alone. The list also included other important buildings that Driesler designed, including Holy Cross Parochial School on Church Avenue, the Chapel of the Nativity in Kenilworth Place, the English Lutheran Church at Newkirk Avenue, the Vanderveer Park Methodist Episcopal Church on Glenwood Road, the Cortelyou Club, and the Borough Park Club buildings.

By the turn of the 20th century, Driesler was designing in brownstone Brooklyn. Contracted by developer William Reynolds, he designed several rows of houses on Sterling Place: Nos. 268-288, 263-391, and 364-396. These were built in 1899. A row of limestone row houses in Park Slope followed in 1903. In Prospect Lefferts Gardens, Driesler was responsible for designing more buildings in that neighborhood than even the more well-known architect Axel Hedman. He began with frame houses on Fenimore Street in 1905, similar to his work deeper in Flatbush, but was soon back to working in brick and stone.

Between 1907 and 1910, he designed the limestone rows on Lincoln Road to Fenimore Street, between Bedford and Rogers, and on Sterling between Rogers and Nostrand. They are all classic two-story and a basement limestones and brownstones in the Renaissance Revival Style, with rounded bays.

In 1906, Driesler was back in Prospect Heights, designing two freestanding homes on Park Place, both handsome limestones with columned porches.

He also designed more houses on Park Place, as well as on Underhill that year. No dust settled on Dreisler; in between his work in brownstone Brooklyn, he was also involved in designing rows of houses in the new suburbs of Mineola, Long Island, and in Borough Park and Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn. In Flatlands, he designed a 28-building plant for the William Becker Aniline and Chemical Works Company. This complex, built in 1916, took up more than three blocks. All of this activity no doubt prompted his colleagues to elect him president of the Brooklyn Society of Architects in 1908.

As the years passed, well into the teens and ‘20s, Driesler kept up his amazing pace. In 1913, he found time to write a column for the Brooklyn Eagle on “The Architect and His Client,” which explained the role each had in the design process. It was a rather pretentious piece of advertising in which he explained that women were only interested in seeing pictures of the house, and in the size of the closets and rooms, and were uninterested in the specs of the building. He also conceded that most men didn’t look at the specs either, and were more concerned about costs than the specifics of design. It all boiled down to trusting the architect to know what was best. Of course.

Driesler worked steadily through to the Great Depression. His name appears in the Builder’s Guide with projects mostly in Long Island and New Jersey as the years pass. Brooklyn was all built up. His son, Benjamin Driesler, Jr. also became an architect and worked in the same genre, designing buildings in Queens and Long Island as well.

In 1949, Driesler died. He still lived in Flatbush, but had been sick for over a year. He died in Kings County Hospital at the age of about 82. His survivors mentioned included two of his five children. His former wife, Anna M. Driesler, and son had already passed away before him. He was a Mason, and they held the funeral service for him, and he’s buried in The Evergreens Cemetery. He had an amazing career, and left behind an impressive legacy of buildings, many of which are in historic districts and still stand. He never achieved the fame of some of his contemporaries, but he certainly exceeded their volume, and his name now is used to sell the houses he designed. He would have liked that a lot, I think.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- 15 Architects Whose Designs Shaped the Look of Historic Brooklyn

- From Woods to City in 18 Months: Fiske Terrace-Midwood Park (Photos)

- Old House Lovers Will Drool Over These Vintage Architecture Trade Catalogs

Sign up for amNY’s COVID-19 newsletter to stay up to date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment