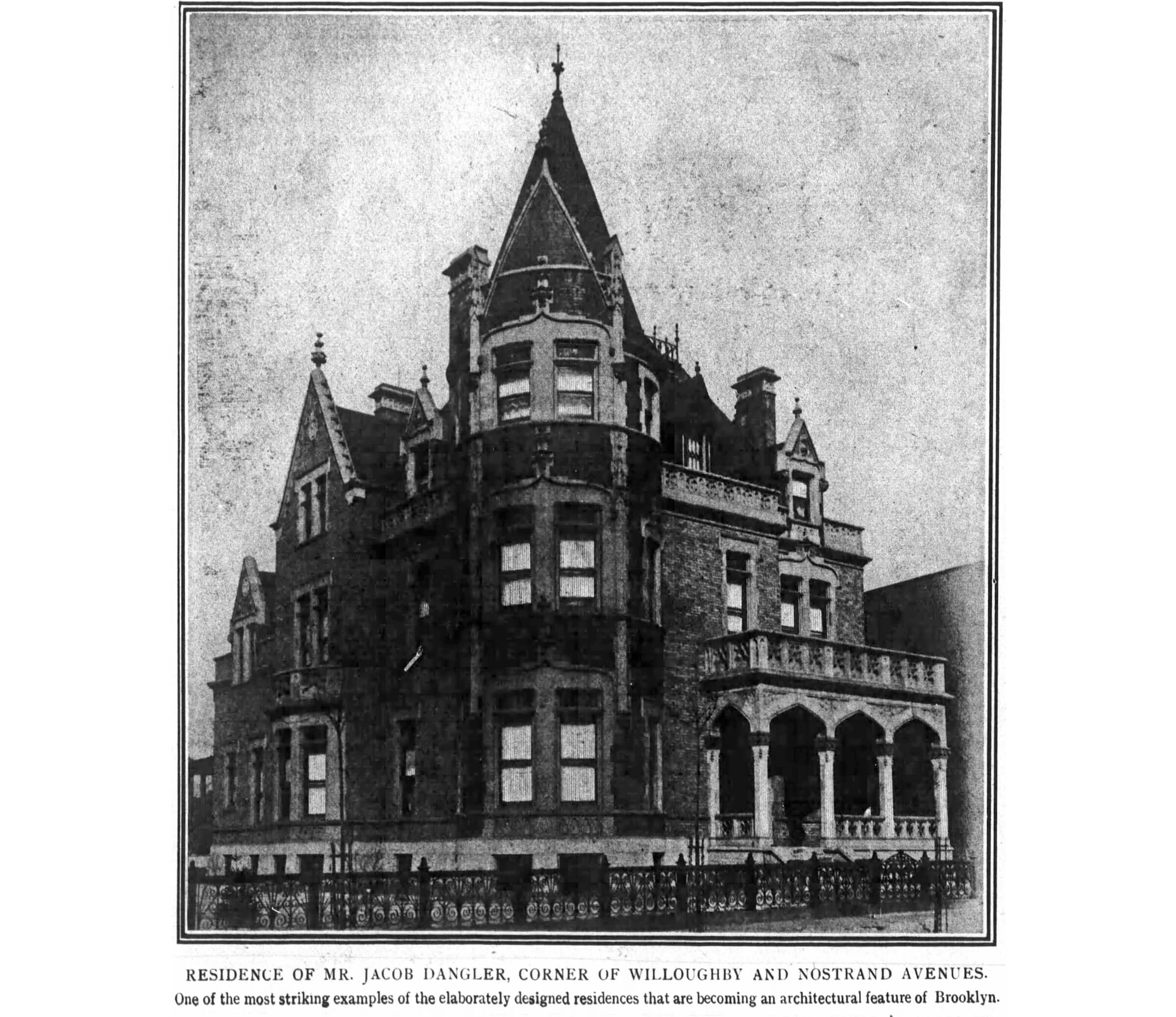

The Grand and Mysterious Willoughby Avenue Mansion of Grocer Jacob Dangler

The golden brick and limestone French Gothic pile is an unusual style for Brooklyn and incongruous with the much more modest brownstone neighbors on the block.

441 Willoughby Avenue. Photo by Susan De Vries

Editor’s note: This story is an update of one that ran in 2013. Read the original here.

The house sits on the northeast corner of Willoughby Avenue at Nostrand Avenue, seemingly empty, sprawling behind a chain link fence. It’s on a large lot, and the house itself, a golden brick and limestone French Gothic pile, is totally incongruous with the much more modest brownstone neighbors on the block. A block away and across the street is the Bedford Stuyvesant branch of Home Depot, and for thousands of people visiting the store, or waiting for the Nostrand Avenue bus across the street, this house may be a fleeting mystery, glanced at when passing through the neighborhood. Even those who don’t care about these things wonder what it was, or how it came to be there. Was this a rich family’s mansion? Who were they? Why did the house sit here, and what’s it being used for now? Is it abandoned? Empty? Has anyone ever been inside?

Well, I’ve been asking those questions for more than 30 years. I saw this house on my first trip down Nostrand Avenue coming into Bedford Stuyvesant, when all of Bed Stuy was a mystery to me, and I’ve long been curious about its former and current inhabitants. Since I fantasize about rescuing houses the way some people rescue stray animals, I’ve always wondered what it would be like to live there, rattling around in that huge house like a rich old recluse, while the neighborhood around you changes over the years. Did anyone actually do that? It turns out the answer to that is no.

I’ve also wondered about how much money it would take to restore a mansion like that, and what are the chances that will happen? How would it look with the porch opened up again, with the windows repaired and the stained glass transoms re-created? How much would it cost to replace the slate roof? What about landscaping around the grounds and the chain link fence replaced by a proper black wrought iron fence, perhaps one with an ornate gate, as befits this French fantasy? And inside? Who knows? This house is a whopping 58 by 85 feet, with over 12,000 square feet of house. Who the heck lived here?

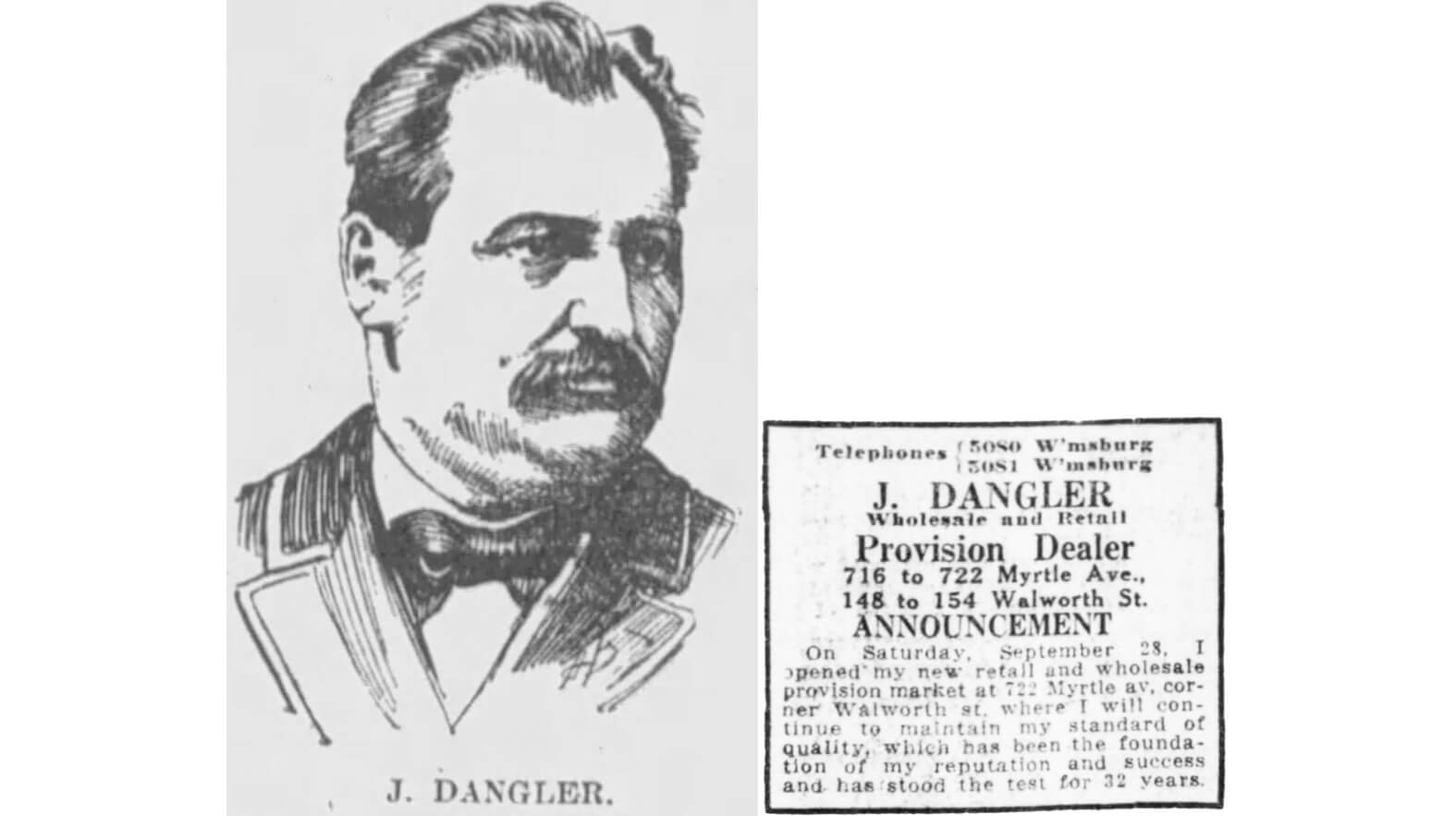

That question was relatively easy to answer, and given that the house is in the Eastern District, on the far northern side of Bedford Stuyvesant, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the man who commissioned the house was of German ancestry, as were most of the wealthy men in this part of town. This was the home of Jacob Dangler and his family, and he was a very successful purveyor of meats and provisions. At least that’s how his empire and long career started.

Jacob Dangler was born in Alsace-Lorraine in 1851, the son of farmers. At that time, this border state belonged to Germany, although now it is a part of France. Dangler came to the United States, landing in Brooklyn at the age of 17. He had an aunt here in Brooklyn and was soon able to gain employment in the grocery business under Henry Meyer, another German grocer who would end up being one of the largest tobacco manufacturers in Brooklyn and Queens. I wrote about him for Brownstoner Queens, here and here. After a year with Meyer, Jacob Dangler moved on to work for Andrew Harman, who had a provisions store on Broadway, in Williamsburg.

Young Jacob discovered he liked provisions, which are what we today call deli meats and cold cuts. He worked for Harman for 10 years, learning the meat processing business, and how to make the finest processed meat products, especially from pork. Like many German immigrants, Dangler saved his money, and during this time, got married, and bought a house in Williamsburg, on South 5th Street. He also began plans to start his own business, and in 1880 opened his own meat and provisions establishment at 734 Myrtle Avenue. Louise Dangler was not just a stay at home wife; she also helped him in the store, and was the bookkeeper for his business. The couple also began a family, and had three sons.

In 1884, his establishment on Myrtle was just too small for his rapidly growing enterprise, and he moved to a larger facility on the corner of Myrtle Avenue and Wallworth Street. In time, he greatly expanded on this facility, using Brooklyn’s most prolific German American architect, Theobald Engelhardt, to design all of the additions, garages and other changes to his property. The family also moved to 734 Myrtle Avenue, just down the block from the business.

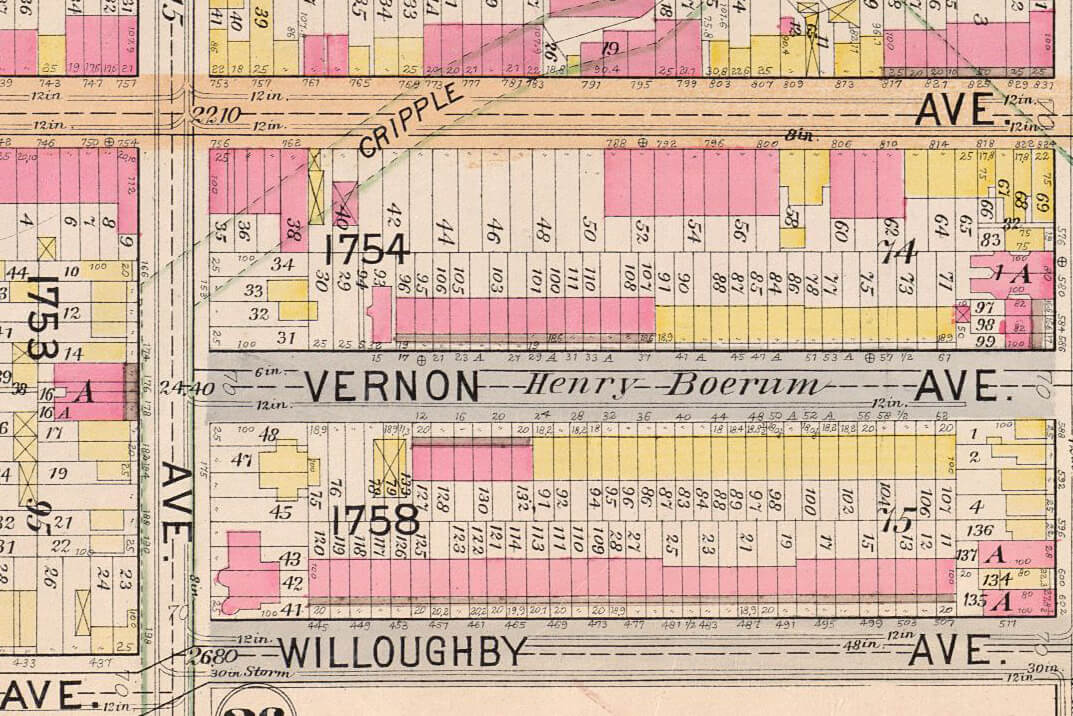

By the turn of the 20th century, Dangler’s business had grown to the extent that he was a wealthy man. Like many such men, he had been approached to join the board of at least one bank, and he was also a real estate investor and landlord, with many residential properties in the Eastern District that he both rented out and bought and flipped. But he was still living in a rather nondescript home on Myrtle Avenue. It was time for new digs worthy of his status. He commissioned a mansion for a piece of property he had bought on the corner of Willoughby and Nostrand avenues.

I tried to find the architect of this house everywhere in my online resources in 2013, but came up empty. But since Theobald Engelhardt designed not only Dangler’s factory, but also several houses on property he developed, I thought it likely Dangler came to him for this project as well. Engelhardt was certainly able to come up with this design and oversee the execution.

Records now available online show that this was correct. Plans for the house were filed in 1897 with Thomas Engelhardt listed as the architect behind the house. It was to cost an estimated $18,000 to construct.

The house is rather interesting in many ways. First of all, the location. It’s only a short walk to Dangler’s business, and I think that was very important to him.

This neighborhood was never upscale. In fact, by the time this house was built, industry was well established on all of the blocks west of here. There were all kinds of factories near here, making all kinds of products. There were lots of homes, as well, with streets of row houses, as well as tenement and flats buildings. There were enough children in the area that a large school, a beautiful Snyder school, would go up a block or two away only a short number of years after the house was built.

The block the house sits on is full of Neo-Grec brownstones on both sides of the street, built in the mid to late 1870s. It was a nice, middle class row, but not the location where one would think a fine mansion would be. A few blocks east of here, on Willoughby, were the large houses of other successful German businessmen, but down this way, Dangler’s house stood alone in its splendor.

The style of the house is interesting, as well. Perhaps Dangler wanted a building that reminded him of that part of Europe that he called home, an area that was pulled between Germany and France with great regularity. When his father had been born in Alsace-Lorraine, it was French. By the time Dangler came along, it was in German hands again.

The design is pure French Gothic, not a style that you see all that often in Brooklyn, although there are other great examples. This was around the same time Montrose Morris designed the French Gothic Clermont Apartments on Decatur Street in Stuyvesant Heights. Also in Stuyvesant Heights on Decatur Street and in the St. Marks District on Park Place, Axel Hedman and Magnus Dahlander had designed some very lovely French Gothic row houses in the 1890s. Perhaps Dangler had admired these as well.

Dangler was also a very pious and religious man. He was a dedicated churchgoer, and a leading member of his Lutheran house of worship, St. Peter’s Church, on the corner of Bedford and DeKalb avenues. Jacob had been a member for many years, and was president of the board of trustees there. One of his sons, Henry, even married the pastor’s daughter. The very Gothic elements of the house’s design could also reflect his religious side. The exterior abounds with trefoils, quatrefoils and other “churchy” elements so familiar to Gothic architecture. But then, I could just be over-thinking it. Perhaps Jacob Dangler just wanted a French castle on his little corner of the universe, where he could be king.

By 1900, the family appears in the census at this address. The Danglers’ activities began to be noticed in the papers around this time. An extensive article in The Brooklyn Citizen in 1898 describes the interior of the house in detail, from the bowling alleys in the basement to the trim in the attic. The finished house was estimated to cost at least $50K. A photograph of the exterior of the house appeared Brooklyn Life in 1901.

In 1903, two of the Dangler brothers got married in a double ceremony. Their choices of brides would warm the heart of any romantic. George Dangler married Louise Humbert, a young woman who had come over from Germany only four years before, and was employed as the housekeeper at the Dangler home. Emily Lohmeyer, the bride of Albert Dangler, was an orphan. She lived with her aunt on Lafayette Avenue and had met Albert while working as a cashier in Jacob Dangler’s store. Both girls were around 23, and were said to be quite pretty.

The wedding took place in Williamsburg at the Knapp Mansion, on Bedford Avenue at Ross Street. The happy couples were going on their honeymoons at Niagara Falls, and when they returned, George and Louise were going to live here at the mansion, while Albert and Emily were moving to 722 Myrtle Avenue, above the family store, where they had met. Today, that building is a health clinic, and has been extensively renovated from the factory/retail space it once was. The third Dangler brother, Henry, married the preacher’s daughter. His wife, Emma Julia Heischmann, was the daughter of Rev. Dr. John Heischmann, the longtime rector of St. Peter’s Lutheran Church, located at Bedford and Dekalb avenues. Henry would go on to become a well-respected doctor.

Jacob Dangler had a very long life, filled by a busy career and a long association with his business, his later banking businesses and with his church. Like many wealthy and successful men, he was asked to be a trustee at a bank. He joined the board of the newly founded Fulton Savings Bank in 1903. Most of the trustees and officers in the bank were fellow German-Americans. In 1935, he became a second vice-president, and a year later, he was made first vice-president. He was on hand to open a new branch of the bank on Flatbush and Caton avenues in 1931, and is in a photograph below. He’s No. 10 in the photograph, holding a portfolio.

He was very active in his church and other charitable activities. Jacob Dangler was president of St. Peter’s church board of trustees, and was also a trustee of the German Evangelical Home for the Aged and a member of the board of trustees of the Williamsburg Hospital, which he also helped found. He also was involved with the funding for Wagner College in Staten Island.

Dangler was obviously a workaholic. His business, which he ran with his son George, grew over the years, as well. He had problems with strikers in 1912, but in spite of that, he survived. His meat products, especially his bologna, were highly regarded and sold well to the growing number of delicatessens and food markets, as the eating habits of Americans changed in the 20th century, and sandwiches became an American necessity for working folks and school children alike.

A busy man needs an automobile, and in the early days of the car, Jacob Dangler shows up on the Automobile Club’s book of registered car owners in New York City. In 1916, his chauffeur, 22 year old Harold Benson, was arrested for felonious assault and reckless driving. He hit a 6-year-old girl on Willoughby Avenue, fracturing her leg. The papers did not mention if anyone else was in the car at the time. The girl was taken to Cumberland Hospital and treated.

Albert Dangler, the son who lived above the store, rescued an entire household of people from a building nearby. The building was owned by his father, who had a lot of real estate in the neighborhood. He was in the building and smelled gas, and broke into an apartment where everyone had succumbed to the fumes. He was able to turn off the gas and get everyone out. They were revived and taken to the hospital. Albert saved the lives of six people.

In 1911, Albert left his father’s business and set up his own business in the Sunset Park area. His business also packed and produced pork and other meat products. He was not as successful as his father, but he did well. Unfortunately, he was never in great health, and died well before the other members of the family. His mother, Josephine, died in 1929, after a long illness.

Jacob Dangler died in 1939, at the age of 87. He had been sick for only a few weeks. Up until that time, he had carried on his usual routine, getting up at 5 a.m. in the morning and walking over to 722 Myrtle Avenue to his business to conduct a full day’s work. He never retired. The funeral was held at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church, and he joined his wife and son in Green-Wood Cemetery. He left behind his other two sons, their wives, eight grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

The house went to George and his wife, who had been living there since they had gotten married. Dr. Henry and his family now lived in suburban Flatbush. The neighborhood had long since changed from when the Danglers built the house, and they were now surrounded by factories and an economically and racially changing neighborhood. Most of the long established Christian German families were long gone, their mansions now home to wealthy German Jewish families.

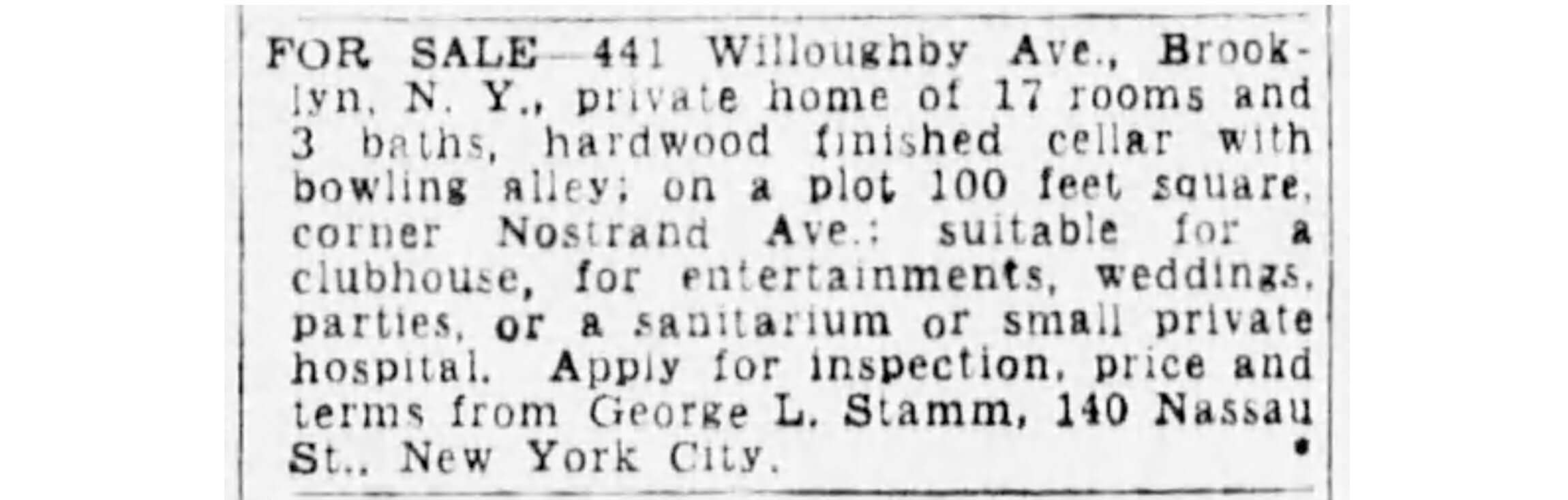

Down on this end of Willoughby, the neighborhood was becoming ethnically diverse, with Jewish, black, Irish and other families moving into the brownstones. Nostrand Avenue had become a noisy and busy vehicular roadway. Two years later, in 1940, the mansion was put on the market. A large ad was placed in the papers, touting the house as an ideal location for a home, club, nursing home, school or funeral parlor.

By 1943, the house was serving as Willow Temple, a lodge of the Knights of Pythias. In 1967, the building was purchased by the Oriental Grand Chapter of the Eastern Star, a masonic organization founded in 1850, for both men and women, although now it is almost exclusively for women. Orders of the Eastern Star are usually founded in conjunction with a male Masonic counterpart. The Order has owned the house ever since.

Over the years, the house underwent many changes. Walls were taken down and the house expanded into large rooms for meetings and parties. A reader commented he had been in the house, and large rooms take up the entire ground floor. An extension was built on the back, further expanding the public space. From advertisements on the Internet, it seems that several Masonic lodges and other organizations use the space. The Dangler family was the only family to ever live here, by all accounts. Totally forgotten today, they left behind only a large mysterious mansion on a busy corner of Bedford Stuyvesant, a monument to success and hard work.

[Photos by Susan De Vries except where noted]

Related Stories

- An Inventive Architect Designs a Bank With Industrial Grit in Williamsburg

- 19th Century Mansions for the Masses in Bushwick

- The Offices of Theobald Engelhardt, Architect

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment