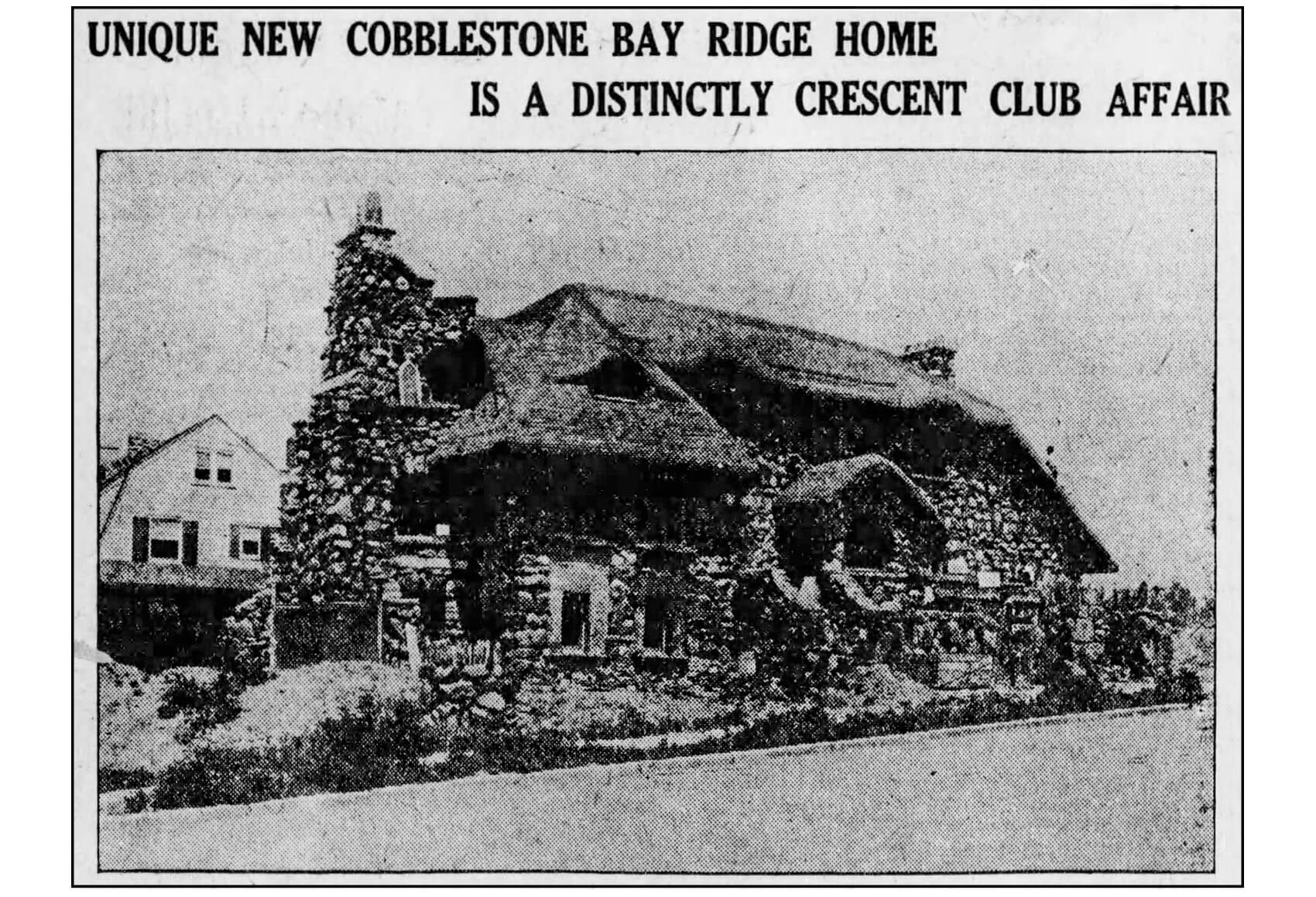

The Story Behind Bay Ridge's Famous Gingerbread House and How It Came to Be

Sometimes it can be hard for a creative person to be defined by only one work, but when that one work makes you a household name, who can argue?

Photo by Susan De Vries

Editors note: This post originally ran in 2011 and has been updated. You can read the previous post here.

Sometimes it can be hard for a creative person to be defined by only one work, but when that one work makes you a household name, who can argue? For James Sarsfield Kennedy, a gifted architect working in the early 20th century, that one work would be the house he designed for Howard and Jessie Jones, at 8200 Narrows Avenue, in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn.

Today, accurately or not, that home is known around the world as the “Gingerbread House”, because it looks like a fairy tale cottage, something out of the world of Hansel and Gretel and European folk tales. In reality, the house is a rare American example of the Arts and Crafts style, originating in the fertile minds of a group of English artists and reformers.

Bay Ridge was originally a part of New Utrecht, one of the six original towns that would one day be Kings County. The Dutch settled this part of New Utrecht in 1657, calling it Yellow Hook, because of the color of the clay found there. A yellow fever epidemic in 1848 and 1849 caused people to change the name to Bay Ridge, after the high glacial ridge rising above the shoreline. The town remained an agrarian community until the late 19th century, when the expansion of the city of Brooklyn finally found it.

Because of the beautiful scenic nature of the shore and surrounding heights, stretching along the Lower Bay and the Narrows, Bay Ridge became a popular suburban retreat, with large mansions stretching along the Shore Road, and on the steep ridge overlooking the bay. Ferry service to Manhattan, to Staten Island, and transit service to downtown Brooklyn made the area quite attractive to wealthy businessmen, who could still commute to work, and then come home to their palatial homes. By the early 1900’s, estates like those belonging to E.W. Bliss, a wealthy manufacturer, and the infamous Diamond Jim Brady enjoyed the magnificent views of the bay.

Another famous and influential “resident” of Bay Ridge was the Crescent Athletic Club. It began as a football club for young Ivy League alumni in 1884, and grew to become Brooklyn’s most prestigious men’s sporting club, attracting many of Brooklyn’s most important, and wealthy men.

The main headquarters was in Brooklyn Heights, but the club expanded to Bay Ridge to be able to have room for more fields for team sports, golf, boating, and other summer activities. They bought the old Van Brunt mansion and grounds near 80th Street and the Shore Road and built a new clubhouse and boathouse, both of which were widely photographed and sold as popular postcards.

The boathouse was a large two story Shingle Style building, surrounding by verandahs, anchored by circular towers. It was designed in 1904 by an architect named James Sarsfield Kennedy.

J. Sarsfield Kennedy was born in Barrie, Ontario, near Toronto, the son and grandson of architects. He came to Brooklyn in 1898, and two years later is on record for his design of 169 Westminster Road in Prospect Park South, one of the earlier houses in Dean Alvord’s upper-middle class enclave in Flatbush. That house is a handsome, but not outstanding Four Square suburban house.

He would also design two more homes in that neighborhood, one being 152 Stratford Road, in 1905, a very similar house to the Westminster Road house, with more Colonial Revival styling. In 1909, he designed a beautiful Beaux Arts townhouse for Charles Meads in Park Slope, and was the architect for several other suburban homes in what is now called Victorian Flatbush.

Perhaps after seeing the Crescent Club’s Boathouse, shipping tycoon Howard E. Jones decided to give this young architect a chance to show his stuff on his own new home. Jones was president of the large shipping firm James W. Elwell & Co, a position he held for almost 23 years. Mr. Jones was also a director of the Maritime Association Board of New York, became vice president of that organization in 1932, and was also an administrative chairman of the local Brooklyn Civilian Defense Volunteers Organization. He and his wife Jessie were also very active with the Victory Memorial Hospital, an organization for which he was president.

In 1915, Kennedy designed a garage for Howard Jones on 81st Street near Colonial Road. Could this have been his “audition” for the Gingerbread House? The Real Estate Record and Builder’s Guide for September 1, 1917 lists the following: “J. Sarsfield Kennedy, of 157 Remsen Street, Brooklyn, N.Y., has plans in progress for the two-story residence, about 40 x 36, at the northwest corner of Narrows Avenue and 83rd Street, for Howard E. Jones, c/o James W. Elwell Co. 17 State Street, Manhattan, owner.”

The architect and his client must have bandied around some ideas, and decided to expand, because by the time the Builder’s Guide announced on September 29th, 1917, that the Rupp Brothers, contractors located on Montague Street, had the building contract, the building had gone from 40 by 36 to 59 by 75. It would cost $25,000. A year later, in 1918, Jones would buy a 100 by 100 foot plot of land on 8nd Street and Narrows Avenue from the Crescent Hill Improvement Company. It cost him $15,000, and gave him ample grounds for the building of Bay Ridge’s most famous house.

Kennedy designed an unusual and magnificent Arts and Crafts Style house for the Joneses. By this time, the Arts and Crafts movement in the United States was in full swing, spurred in part by many of the ideas of Henry Hobson Richardson, masterpieces on the West Coast by Greene & Greene, Gustav Stickley’s picturesque bungalows on the East Coast, and the Prairie Style of Frank Lloyd Wright and others in the Midwest. But Kennedy’s inspiration went to the source: the English Arts and Crafts styles of architects like Richard Norman Shaw and the writings of John Ruskin and William Morris.

They, as well as their followers in America, wanted to return to the ideals of handmade craftsmanship, lost in the mass production of the Industrial Revolution. They advocated the use of natural materials and a return to the land by way of rustic architecture, furnishings and living. What could be more rustic than a house made of stone and rubble, with a naturalistic and organic roofline, mimicking the thatched roofs of the English countryside?

The rambling house is made of uncut stone, in varying shapes, colors and sizes. It uses the topography of the lot, conforming to its rises and falls, and does not force the land to conform to the design of the house. The porte-cochere seems to buttress up the house, while the striking wall of chimney on the southern end of the house, on a higher elevation than the other side, holds the house up on that end.

It’s a brilliant and organic way to make the land work for the design. The main entrance is under a charming archway, and the house just rises in irregular lines, with irregular and wonderfully placed windows, capped by an organic and charmingly undulating asphalt shingle roof, which must be a roofer’s nightmare, in polychrome shingles that wrap around rounded edges and up under eyebrow windows.

It may be a storybook design, but the common appellation “the Gingerbread House” masks the subtlety and nuance of this design. This is not a silly folly of a house. Amidst the stone and shingles are elements of a modern, almost Prairie Style stucco house, best seen on the northern and southern sides, where rows of casement windows add a measure of order to the otherwise organic growth.

From photographs used in recent sales listings, the interior of the house appears to be in the Craftsman mode, with classic bungalow style beamed ceilings and wainscoted walls.

A 1918 article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle described the interior as “English oak.” The garage once had a turntable that allowed a car to always face the entrance without backing in, but that feature no longer works.

The house is also graced with another Arts and Crafts feature, a wealth of whimsical hand-wrought ironwork, in the form of the fences and ornate gates, as well as the lanterns and downspouts.

The house sits on a large lawn, with a back extension, an enclosed garden and the garage. Other wonderful little details include the traditional English garden fence in the back, the red chimney pots and the perfectly unexpected window smack in the middle of the chimney wall. Absolutely brilliant!

The Jones’ must have been thrilled with their house, although it was probably a tourist attraction from the day it was finished. Kennedy would go on to design a very Wrightian, Prairie School meets Italian villa, at 109 Rugby Road, in Prospect Park South.

This 1920 house again combines disparate design elements, showing the workings of a mind that saw connections between styles that many other architects did not. Some of his efforts are a bit jarring, but they are all interesting.

Kennedy died in 1946, with a decent portfolio of work, but never again achieved the level of brilliance achieved in the Jones house. How do you top that? It’s simply one of a kind, and very, very good.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless where noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- J. S. Kennedy and the “Modernization” of Brooklyn Heights

- Building of the Day: 109 Rugby Road

- Gingerbread House Drops Price Again

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment