A Sentinel Overlooking Brooklyn Heights Promenade Has Seen Some Ghosts in Its Time

Attracting artistic residents for at least a century, a Neo-Grec brownstone mansion facing the Brooklyn Heights Promenade played a leading role in a 1977 campy occult thriller.

Attracting artistic residents for at least a century, a Neo-Grec brownstone mansion facing the Brooklyn Heights Promenade played a leading role in a 1977 campy occult thriller, counted among its inhabitants the creators of “I Left My Heart in San Francisco,” and is today a co-op whose members are close enough to occasionally host a building-wide party. Despite changes and conversions over the years, 10 Montague Terrace retains a remarkable number of features original to its 1875 construction — even a coat closet with the original hooks in a shared hall, now deeded to the occupant of the former library.

In the opening scenes of “The Sentinel,” a realtor describes 10 Montague Terrace as standing on “one of the nicer tree-lined blocks in New York,” and by nearly anyone’s standards – let alone a realtor’s – the compliment is an understatement. As for the building, a classic of brownstone architecture, its imposing presence and magnificent interior made it the perfect setting for an atmospheric horror film. And if the “The Sentinel” mostly left critics cold, the film still does a wonderful job of showcasing one of Brooklyn’s grand mansions.

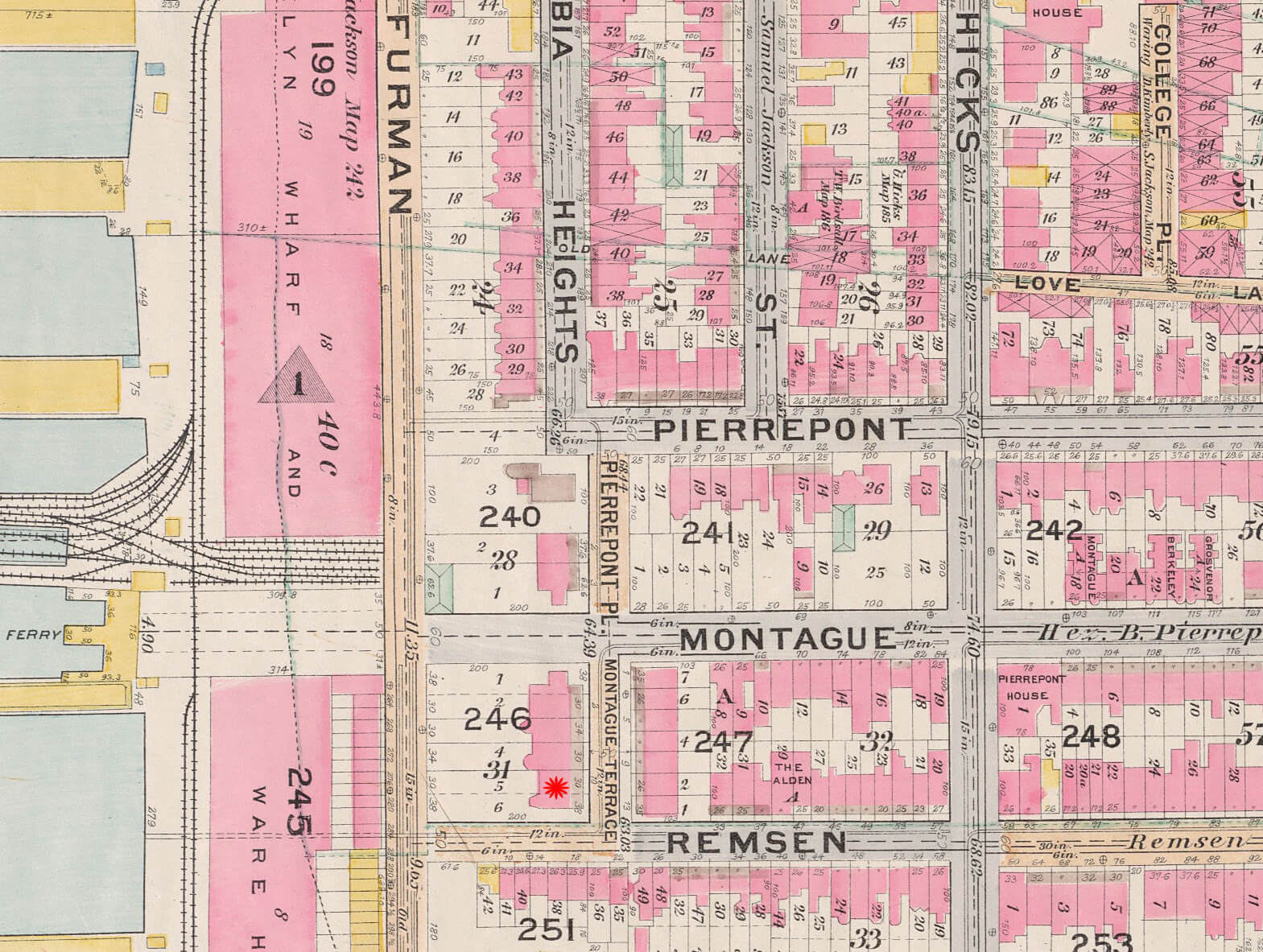

The street now known as Montague Terrace stands on the site of the former Pierrepont estate, which was gradually subdivided by Hezekiah Beers Pierrepont beginning in 1816. The houses that line the block-long street were constructed in the 1870s (a pleasant Colonial Revival apartment building replaced two houses in the early 20th century). In 1872, prominent citizens Henry Sanger and his wife, Mary (née Requa), acquired two adjacent lots; their new house was built on the corner of Montague Terrace and Remsen Street, affording waterfront access and garden views of New York Harbor.

The brownstone at 10 Montague was designed by Ebenezer L. Roberts, whose output included the striking South Brooklyn Savings Institution at 160 Atlantic Avenue and the Charles Pratt House, now St. Joseph’s College Founders Hall, at 232 Clinton Avenue. Reported in the Brooklyn Eagle as costing “about $175,000” to construct, the house was praised as “a palatial new residence” and is a striking example of Neo-Grec architecture that also includes some Italianate and Queen Anne elements.

The house’s exterior incorporated classically derived window hoods, a dentilled cornice and a massive stoop sweeping up to the parlor floor (the last feature was removed some time after 1940). Front, side and rear gardens surrounded the house, and the interiors are finished with cherry, oak and bird’s-eye maple cabinets, mantels, pocket doors and shutters. A monumental staircase winds around a wide central hall connecting the parlor floor’s grand rooms.

The Sangers were prominent members of Brooklyn Heights’ elite, drawing their considerable fortune from Mr. Sanger’s dry goods business. This later blossomed into a profitable partnership with merchants William Cary and Samuel Howard to become one of the most luxurious stores in Manhattan, the firm of Cary, Howard & Sanger. Housed in a now landmarked masterpiece of cast iron architecture in TriBeCa, the store boasted more than $3 million in annual sales of “the taste and ingenuity of three continents” with “1,500 different kinds of domestic and fancy goods” available, according to a contemporary business chronicle of the time quoted by Daytonian in Manhattan.

The Sangers entertained frequently at their grand home, where they also raised five children, two boys and three girls. The Brooklyn Eagle records numerous instances of Mrs. Sanger’s “at-homes” while Mr. Sanger served terms as the president of the old Brooklyn Academy of Music (then nearby on Montague Street) and on the board of directors for the Brooklyn Hospital, the Packer Institute and the Art Association. In addition to their architectural legacy in Brooklyn Heights and Manhattan, the Sangers were one of the seven families to commission the Seven Sisters in Montauk, the famous Shingle-style development by Stanford White, and spent their summers there and in Saratoga.

Mr. Sanger died in 1886; of his children, the most prominent was the diplomat and lawyer Colonel William Cary Sanger, who, after a stint with the National Guard, served as Assistant Secretary of War under both William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. A tireless advocate for Republican causes and a proponent of the draft, Sanger ran twice for assemblyman and served as the president of the delegation to the Geneva Convention in 1906. Married to Mary Ethel Cleveland Dodge and father to a large family, he constructed a vast estate near Albany called Sangerfeld and, as time went by, spent more and more of his time there.

In his absence and after the death of his mother in 1910, his unmarried sister, Lillian Sanger, became the principal full-time resident of 10 Montague Terrace. She lived there with five servants and a visiting friend or relative, Isabelle Grantham, a nurse, with whom she occasionally traveled to Santa Barbara. Colonel Sanger died in 1921, leaving his sister life residency at the Brooklyn house, where she continued to oversee a number of social events in the genteel style expected of her clan. These soirees included various entertainments given for her two nieces, the colonel’s daughters, including a reception for the elder, Mary, when she married in 1923.

Such entertainments would become increasingly rare on Montague Terrace; the arrival of the subway in 1908 had changed the exclusive character of the Heights, and listings for furnished apartments in the row opposite the Sanger House began to appear as early as 1912. Apartment buildings sprouted up and the grand villas began to be demolished or cut up into rooming houses. By 1925, literary critic Edmund Wilson wrote disparagingly of what he saw as the physical and social decay affecting the Heights: “The pleasant red and pink brick houses…seem sunk in a final silence. In the streets one may catch a glimpse of a solitary well-dressed old gentleman moving slowly a long way off; but in general, the respectable have disappeared and only the vulgar survive.”

Miss Sanger surely would have argued otherwise, but she was an increasingly isolated holdout. When she died in 1932, the house was advertised the following year under “Rooms for Rent – No Board” as providing “immense studios, bath, overlooking harbor.” The address was still thought a respectable one; the Brooklyn Eagle was happy to report the 1940 betrothal of Miss Eileen Lovett to Mr. John M. P. Wallach “of 10 Montague Terrace” – but from the ‘30s through the ‘50s the neighborhood acquired an air of decline.

Along with this, however, came a new popularity with artists and writers — particularly those seeking cheap rents. Opposite 10 Montague, the British poet W.H. Auden lived at No. 1 Montague Terrace, author Thomas Wolfe at No. 5 (misidentified as No. 10 in a memoir by his secretary) and playwright Henry Miller at 92 Remsen Street. The infamous “February House” stood at 7 Middagh Street, and Norman Mailer, Marilyn Monroe, Hart Crane, Truman Capote, Richard Wright and Gypsy Rose Lee were among those who frequented or lived in the neighborhood.

10 Montague itself lays a claim to this era of what Capote called “splendid contradictions” in the works of George Cory, a composer who lived in relative obscurity but who wrote the music for the ballad “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.” Later made famous by Tony Bennett, the song was composed in 1953 when Cory lived at 10 Montague Terrace with his boyfriend Douglass Cross, who wrote the lyrics. Cory and Cross were desperately unhappy in Brooklyn and Cory was homesick for life in California. He and Cross wrote more than 200 songs together but only 30 were ever published, and “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” was their only commercial success. They left Brooklyn for California, never to return, in 1956, just a few years after the Brooklyn Heights Promenade and the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway opened right outside 10 Montague Terrace’s back windows.

The building was at that time owned by the brother of Democratic party councilman George Swetnick, who maintained an apartment there. According to Joseph Wolfson, a tenant of more than 50 years, Swetnick had a plan to knock down both 10 Montague and the house next door at No. 8 to construct an apartment house. Refusal on the part of his neighbors to sell put paid to that idea, and the house subsequently passed into the hands of a man whom George Cory might have kicked himself a few times for not sticking around to meet, the celebrated arranger Milt Okun, whose work included collaborations with Peter, Paul & Mary, John Denver, Placido Domingo and Jim Henson’s Muppets. Both Okun and his parents lived at 10 Montague, where, Wolfson told Brownstoner, Okun was a benevolent landlord.

Certainly the same could not be said of the fictional owners of 10 Montague Terrace in “The Sentinel.” (Oddly enough, in the movie, the building is identified by its actual address.) The film implies the building is owned by the Catholic Diocese and represented by the obsequious Miss Logan (Ava Gardner), who immediately lowers the rent on a suite of fantastic high-ceilinged rooms when Alison Parker (Cristina Raines) balks at the $500 monthly price tag. Alison is seeking a refuge from her Manhattan life with her possessive boyfriend (Chris Sarandon). But nothing is what it seems: Strange sounds and grisly dreams trouble her nights. Could the sightless priest on the top floor be holding back some terrible secret – perhaps even the forces of capital-D Darkness?

Well, duh. Alison finds herself besieged by ghosts and pestered by annoying neighbors, who then turn out to be more ghosts. Warhol fixture Sylvia Miles makes an appearance as a phantom ballerina while a party-hat-wearing cat pops up to devour Satan’s canary. Brains are munched, cymbals clashed and the gateway to hell yawns open, pouring forth shambling ghouls. In a touch that many found offensive, Wolfson among them, some of these were played by people with chronic deformities; in his biography British director Michael Winner claimed he was giving them the spotlight while also pointing out that he saved a bundle on makeup effects.

But for all its wrought-iron hokum and politically incorrect ickiness, the film is an unexpected trove of appearances from both established stars and the up-and-coming New Hollywood generation, balancing out roles for Gardner, Miles, Burgess Meredith (amusingly avuncular as Old Scratch himself), Jose Ferrer, Jerry Orbach and Eli Wallach with early screen appearances by Christopher Walken, Chris Sarandon, Jeff Goldblum, Beverly D’Angelo and Tom Berringer, in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-him walk-on role.

Past that, the star of the film is 10 Montague itself, which takes its big-screen place among such great spooky New York locations as The Dakota (Rosemary’s Baby, 1967) and 55 Central Park West (Ghostbusters, 1984), with creaking stairs, shadowy landings and swinging chandeliers galore – all still intact and in place to this day. Wolfson recalls that for the shoot, the entire building, fully occupied by renters, was emptied of furniture after each room was photographed extensively so that movers knew precisely where to return every object. “I bought a BMW with what they paid me,” he said. “But [I] had to ask them to leave after they violated their agreement not to use my apartment as a waiting room for staff.”

The building went co-op in 1986 and again appeals to a creative cross-section of New York; current tenants include architects, interior designers, artists and musicians. A recent arrival says of the place: “I couldn’t believe my eyes when I stumbled across the listing. It’s such a unique and beautiful space—the high ceilings, architectural detail, endless bookshelves, fireplace, giant bay window. And to have all that looking out over the New York Harbor seemed too good to be true.”

Co-op board chair Andrew Zeif says his introduction to 10 Montague came through his wife, who saw a listing. “The elegant proportions, amazing garden, virtually original interiors were too much to pass up. There’s an incredible esprit de corps in the building; it’s a wonderful group of lovely and caring neighbors. You have proximity to the Promenade, one of the most wonderful urban jaunts anywhere. And then the preservation and viewshed conditions ensure sight lines and respect for timeless design. We’ve become big believers in living in landmarked areas.”

The Promenade is facing a potential threat from plans to rebuild this section of the BQE, but Wolfson, who has lived in the house for over a half a century, believes the special qualities of the house will endure. “I can’t think of a more lovely location in the entire city.”

— Additional historical research by Susan De Vries.

Related Stories

- The Story of Brooklyn’s Grand Stage, the Brooklyn Heights Promenade

- The House That Hats Built, a Queen Anne Manse in Brooklyn Heights

- Past and Present: The Pierrepont Mansion

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment