Preservationists Protest Demolition of Landmarked Buildings Across City

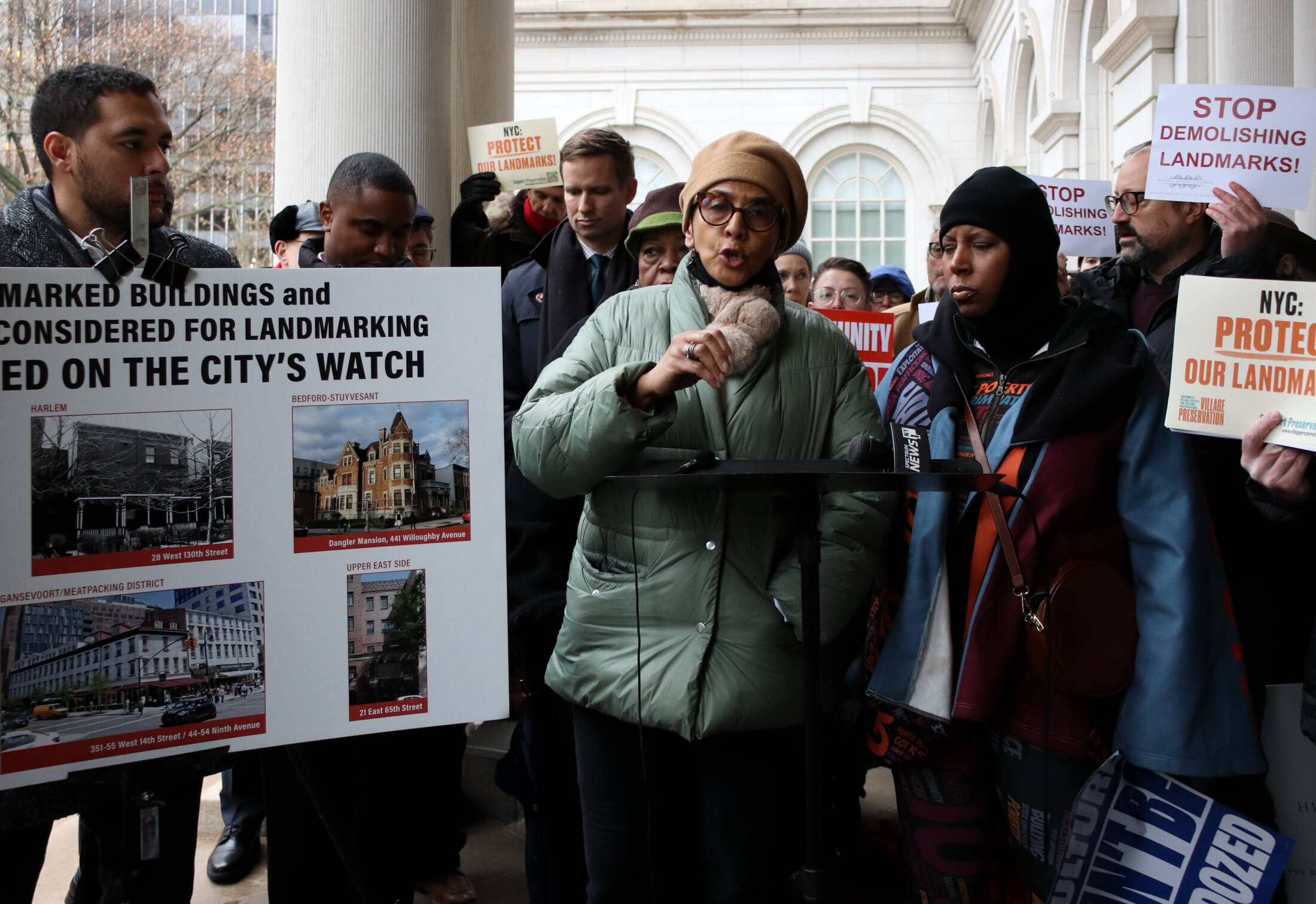

Angered by the razing of landmarked and calendared properties throughout New York City, dozens of preservationists, pols and neighborhood activists called for change at a gathering on the steps of City Hall Thursday afternoon.

Bed Stuy resident Michael Williams spoke about the loss of 441 Willoughby Avenue. Photo by Susan De Vries

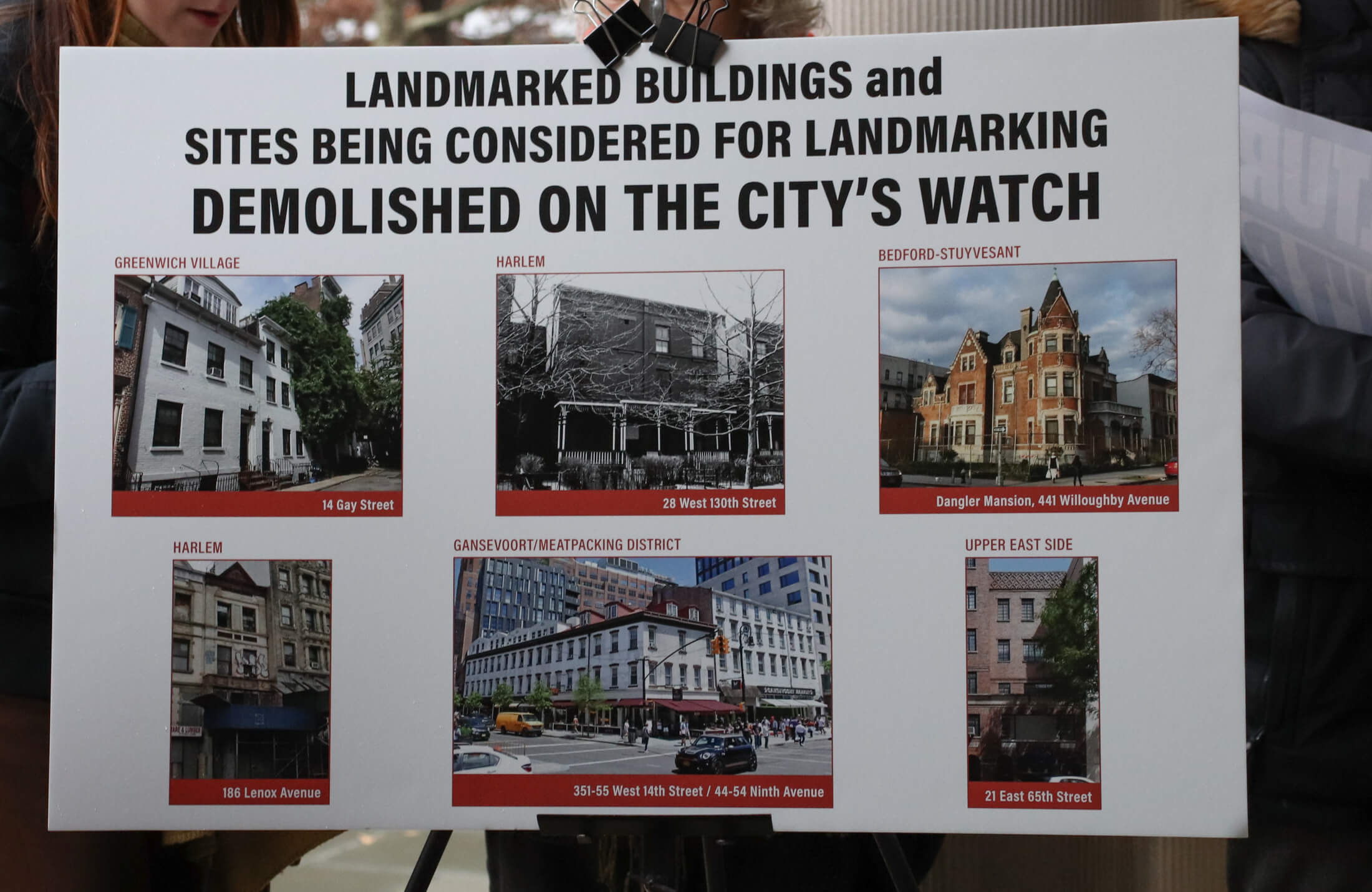

Angered by the razing of landmarked or calendared properties throughout New York City — including the Jacob Dangler mansion at 441 Willoughby in Bed Stuy and literary landmark 14 Gay Street in Greenwich Village — dozens of preservationists, pols and neighborhood activists called for change at a gathering on the steps of City Hall Thursday afternoon.

“To lose these buildings is a deterioration of our culture,” said a member of the Mount Morris Park Community Improvement Association. “We’re not only speaking about physical structures. We’re speaking about the soul of Harlem. The soul of Black people.”

An 1886 row house at 186 Lenox Avenue in the Mount Morris Park Historic District and an 1882 house at 28 West 130th Street in Astor Row in Harlem recently were both ordered demolished by the Department of Buildings after years of owner inattention.

“Those buildings matter because they tell me who I am and where I am every day,” said another member of the Mount Morris Park Community Improvement Association.

Lifelong Bed Stuy resident Michael Williams said of the Dangler mansion: “That building meant a lot to me and people in the community. To see it’s no longer there on the corner of Willoughby and Nostrand is horrible. I cry every day when I walk by.”

While the razing of protected historic buildings is by no means unheard of, typically due to neglect, it has in the past been relatively rare. In the last 18 months, more than a dozen such structures have been demolished, according to preservation nonprofit Historic Districts Council, which helped coordinate Thursday’s event. Reasons vary and include construction mishaps that appear either careless or calculated and, in the case of the Dangler mansion, a city error due to a lack of communication between the Landmarks Preservation Commission and the Department of Buildings.

City agencies, including LPC and DOB, are breaking the Landmarks law by allowing demolition to occur, contend preservationists. Some even go so far as to accuse the city of “collaborating” with developers to destroy New York City’s heritage.

The Landmarks law is the the only means to protect “our beloved landmarks that people from all over the world come to see,” Executive Director of Village Preservation Andrew Berman told the crowd Thursday. “There have been 14 demolitions in a year. There is no excuse. The system is broken and the system must be reformed.”

“We’re all here today because we’re outraged at what we’re seeing in New York City,” he continued. “All you have to do is neglect your building…and city agencies will turn a blind eye…or work with you to demolish your building. That is unacceptable.”

Berman cited a case where records accessed via a Freedom of Information Act request showed the LPC was coaching developers on what to say during landmark hearings. City Council member Chi Ossé of Bed Stuy and Crown Heights and neighborhood group Justice for 441 Willoughby Thursday called for Landmarks chair Sarah Carroll to resign. Council Member Erik Bottcher of District 3 in Manhattan and Councilman Christopher Marte of District 1 in Manhattan were other elected officials who spoke at the event.

Several speakers said they do not oppose construction of new buildings and they welcome affordable housing, but they also want to see the city’s heritage protected.

The groups will discuss and present a list of reforms in the future, Historic Districts Council Executive Director Frampton Tolbert told Brownstoner. Meanwhile, some of the attendees at Thursday’s gathering have already proposed a variety of ideas. Options being discussed include better monitoring by LPC, improved communication and transparency between city agencies and with the public, mandating the city to appoint an administrator when a landmark owner does not respond to violations (as the city already does to safeguard tenants from landlord neglect), and creating a public database of at-risk properties.

The city should require developers who destroy landmarks to “rebuild the building as it was before, which would obviously be much more expensive than if they just kept it,” Berman told a neighbor of 14 Gay Street in November, Brownstoner sister pub The Villager reported.

Landmarked buildings currently at risk in Brooklyn include the Wyckoff-Bennett house, the abolitionist house on Duffield Street and the Duffield Street houses.

The Duffield Street houses, empty and deteriorating for years, have just sold for $10 million, according to a temporary Instagram post from a commercial real estate agent. In May, he posted the site comes with “100,000 buildable square feet” for a buyer who is “landmarks savvy.”

“If you are a developer with landmarks experience you are a buyer for this + will get paid for your skill set via a heavily discounted land basis. call…to discuss or email at…for materials and to set an intention to learn more.. this could be “the project” that changes a career,” said the post.

The marketing and sale of the Duffield Street houses as a development site perhaps indicates the degree to which developers in recent years have been able to work around the Landmarks law by building around, inside or on top of landmarked structures. Such projects carry risk to the historic buildings. In a number of cases, development has resulted, intentionally or not, in the destruction of adjacent landmarks. An 1881 row house at 21 East 65th Street in the Upper East Side Historic District recently was demolished by the city after construction of an adjoining tower cracked its facade.

“Cases like 21 East 65th Street illustrate the real structural risk of projects which preserve only superficial facade elements, and clearly point to the inadequate LPC and DOB oversight and approval process for such complex, surgical work,” said Rachel Levy, executive director of Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts, in a statement. “Reform of these agencies’ processes is critical, or we will continue to see more unnecessary losses citywide.”

In 2015 in Brooklyn, a Greek Revival wood frame house with Italianate details at 69 Vanderbilt was torn down by the city after years of owner neglect. But in the past, other threatened landmark structures have sometimes fared better, including a trio of row houses on MacDonough Street where unpermitted foundation work caused a partial collapse, the Susan B. Elkins house at 1375 Dean Street, and a once-neglected property at 173 St. James Place.

Last month in Greenwich Village, 14 Gay Street was demolished after a contractor hired by the owner removed a large section of one of the house’s masonry walls. The catastrophe also threatened the landmarked house next door at 16 Gay Street, which has been saved. LPC has reportedly required the developer to preserve 14 Gay Street’s building materials to use to rebuild the structure.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission and DOB said in a joint statement published by NYI they are both working to identify at-risk properties and better monitor them when needed.

“The Adams Administration is working to identify other landmarked properties around the city that could be at risk of suffering a similar fate, and working to intervene with additional supervision to prevent situations like this from happening in the future,” according to the statement. Brownstoner has reached out to the LPC for further comment but has not yet heard back.

[Photos by Susan De Vries except when noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- Bed Stuy Locals Rally to Stop Sale of Dangler Mansion Site, Call for LPC Chair to Resign

- The Deteriorating Details of the Empty Little Landmarks of Downtown Brooklyn

- What’s Next for the Landmarked House at 227 Abolitionist Place-Duffield Street?

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment