A Masterpiece of Education: Flatbush’s Erasmus Hall Academy and High School

One of the most important 18th century buildings in the city, Erasmus Hall Academy now sits at the center of a grand early 20th century high school.

Eramus Hall Academy in 1966. Photo via the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission

When the Dutch and then the English established settlements and towns in Brooklyn in the late 1600s, aside from homes, the first three buildings to go up were usually a church, a tavern and a school. (Not necessarily in that order.) It was felt that it was important for a free man to be able to read the Bible, sign his name, and do simple arithmetic. Farmers as well as townspeople needed to be able to “do sums,” as mathematics were called, and have the basic reading skills needed to function in their society.

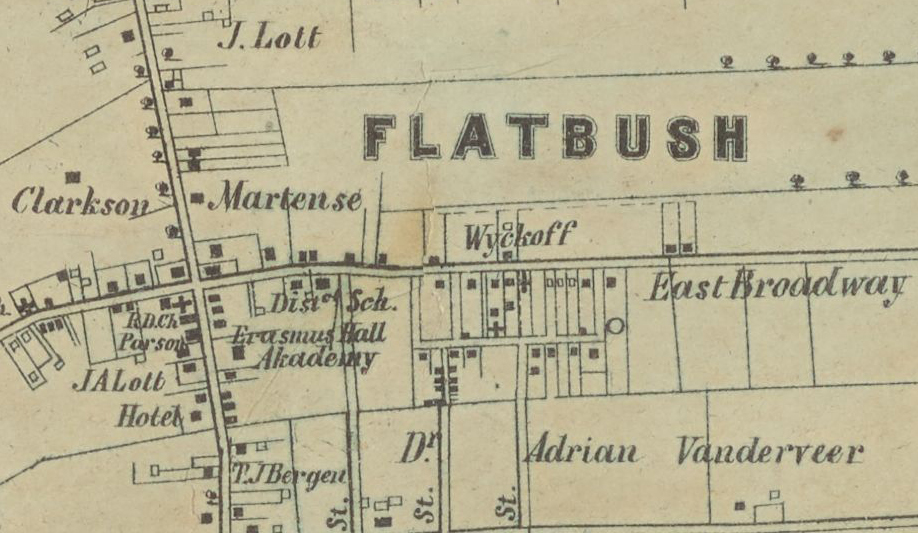

The earliest schools were established and run by churches. In 1659, Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch governor of New Amsterdam, mandated that a school be established in the village of Midwout, now Flatbush. A one-story stone building was built on a parcel owned by the Dutch Reformed Church, already established just across the street. Today, that’s the corner of Flatbush and Church avenues.

The school was directly tied to the church. The first headmasters of the school were sextons in the church, served as choristers, and were called on to conduct services and deliver sermons, should the pastor for some reason be unable to do so. Church records show that an early teacher named Johannes Van Eckellen, who served from 1682 to 1700, had much more in his day than simply teaching a few classes.

In addition to the above functions, his contract required him to begin school at 8 a.m., break from 11-1, and then continue to 4 p.m. He was required to ring the school bell in the morning. Children were required to read the morning prayer and close with prayer before lunch and repeat after lunch. He taught catechism, answered theological questions, and prepared students on Wednesdays and Saturdays for the service on Sunday.

Van Eckellen had to keep the church clean, serve as a chorister, ring the church bell three times before a service, and read a chapter of the Bible in the church between bell ringing. He had duties regarding being present for baptisms, for which he was paid extra, and to top it off, he was the grave digger and tolled the bell at funerals. And presumably he taught his students reading, writing, and arithmetic somewhere in there. Whew!

A hundred years later, in 1786, Reverend John H. Livingston and Senator John Vanderbilt founded Erasmus Hall Academy on the site of the original school. It was the first secondary school chartered by the NY State Board of Regents. The school was intended to be an elite private school for boys. Livingston was the first principal. The land for the school was donated by the Dutch Reformed Church, which still held title to the land where the original school was located.

The two-and-a-half-story school was a wood-framed Georgian/Federal-style structure, with a pitched roof, an impressive columned porch, dormers, and clapboard siding. It was named for Dutch humanist, priest, and scholar Desiderius Erasmus, who lived from 1469 to 1536. He was an early advocate of education for children, among his many accomplishments. He was the author of the famous quote, “In the kingdom of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.”

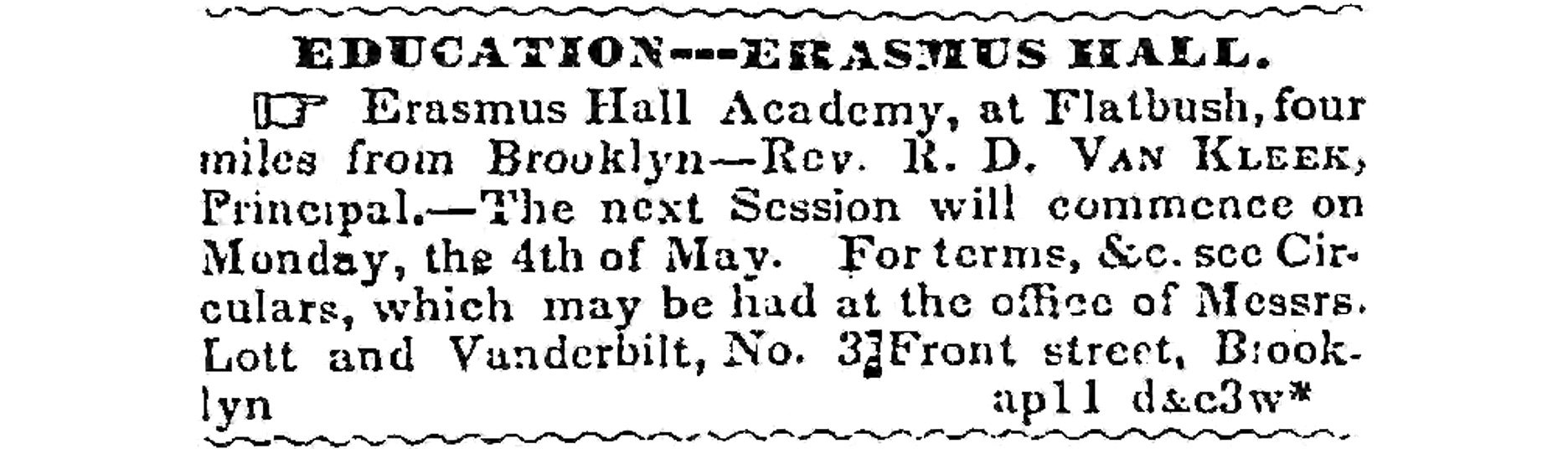

The school was not just for day students, it also housed boarders, most likely under the eaves. The money for the school came from the church and elite sources, including Reverend Livingston, Aaron Burr, Peter and Jacob Lefferts, and Alexander Hamilton. It opened in 1787 with 26 students. The Academy began accepting female students in 1801, and two years later it incorporated the village school of Flatbush.

Over the course of the 19th century, the school cycled through many principals and teachers, including one Jonathan Kellogg who became principal in 1823. He is credited with establishing what were then modern methods of teaching and was in place for the construction of the first of several annexes added to the original building. He was in charge for 13 years but had to resign in 1834 after “falling victim to the habit of drinking the good rum of the old Dutch farmers,” according to the Brooklyn Daily Times.

But at the turn of the century, enrollment was down and expenses were rising. The Board of Trustees wanted to unload the school, which was now considered a “white elephant,” to Brooklyn’s Board of Education. One might think that it wouldn’t be hard to transfer the title, but there was a great deal of drama involved, money of course, and disagreements over what kind of school the building should house. The Board of Ed wanted a high school, which was a relatively new concept in education. The Board of Trustees felt that the school was too removed from public transportation and too far from the population centers of Flatbush. But the deal was finally struck.

In 1896, just two years after Flatbush was annexed to the city of Brooklyn, and two years before Brooklyn became part of greater New York City, Erasmus Hall Academy became Erasmus Hall High School. The Trustees’ agreement stipulated that the Board of Ed build a new high school on the site. Twenty architects submitted plans for the new school, but the costs would be over a million dollars, which was too expensive, and the plans for the new school were dropped. The architects were not paid for their work and threatened to sue, and the Board of Education had to authorize a $200 payment to each of them.

A series of renovations and repairs were made in the interim. Everyone had high hopes for the school, but it was immediately apparent that the building, even with its annexes, was nowhere large enough to accommodate the number of students expected to enroll. Then in 1898, Brooklyn became part of New York City, and the Board of Education of the City of Brooklyn was no more as an expanded NYC Board of Education took over. Erasmus Hall was now their problem.

A new Erasmus Hall High School

In the beginning years of the 20th century, the expanded Board of Education was facing a massive influx of new students as more and more immigrants settled throughout New York. Records show that between 1900 and 1904, 132,000 new students were added to the school system. The entire city needed new elementary, intermediate, and high schools. The Board of Ed authorized the construction of one new, larger high school for each of the boroughs. Brooklyn would get a new Erasmus Hall High School.

Its design would fall to Charles B.J. Snyder, in charge of creating and maintaining all schools in the entire city.

Born in Saratoga Springs in 1860, Snyder moved to Manhattan in 1878 at the age of 18, according to “From Farm Factories to Palaces,” by Jean Arrington with Cynthia S. LaValle. He attended Cooper Union at night while working by day, apprenticed with a master carpenter, graduated in 1881 with Certificate in Practical Geometry, and later earned another in Elementary Architectural Drawing.

As early as 1882, before Brooklyn merged with greater New York City, Snyder was filing plans for building alterations with the Manhattan Department of Buildings. In 1891, he was chosen almost unanimously to be the Superintendent of School Buildings for Manhattan and the annexed Bronx, succeeding George W. Debevoise.

After the 1898 consolidation, he handled the same duties — design, construction, and maintenance — for all school buildings across the city. New construction was not his only task, although that certainly would be enough for three people, but he also had existing schools under his control, and was in charge of their upkeep, additions, or replacement. He had a cadre of deputy superintendents who reported back to him, each responsible for a single element of each school, such as planning, plumbing, heating and ventilation, electricity, furniture, and records.

The need for new schools was so great in this early part of the century that Snyder would often use the same basic design for several schools. He is best known for his innovative “H” plan schools, which created two interior courts, allowing light and ventilation in the classrooms. This also cut noise from the street. His ideas and innovations were widely published and were adopted by school builders across the country.

Snyder is credited with introducing the Collegiate Gothic style of architecture to public school architecture in New York City. Collegiate Gothic was just being introduced in other parts of the country. The style was used in universities but never before in public schools. Snyder’s greatest school designs are in that style, borrowing elements of the buildings in England at Oxford and Cambridge universities. The architects of other American schools, colleges, and universities adapted the style as well, so much so that Collegiate Gothic became synonymous with learning institutions. Snyder designed many beautiful Collegiate Gothic schools during his tenure, but his design for Erasmus Hall High School is perhaps his masterpiece.

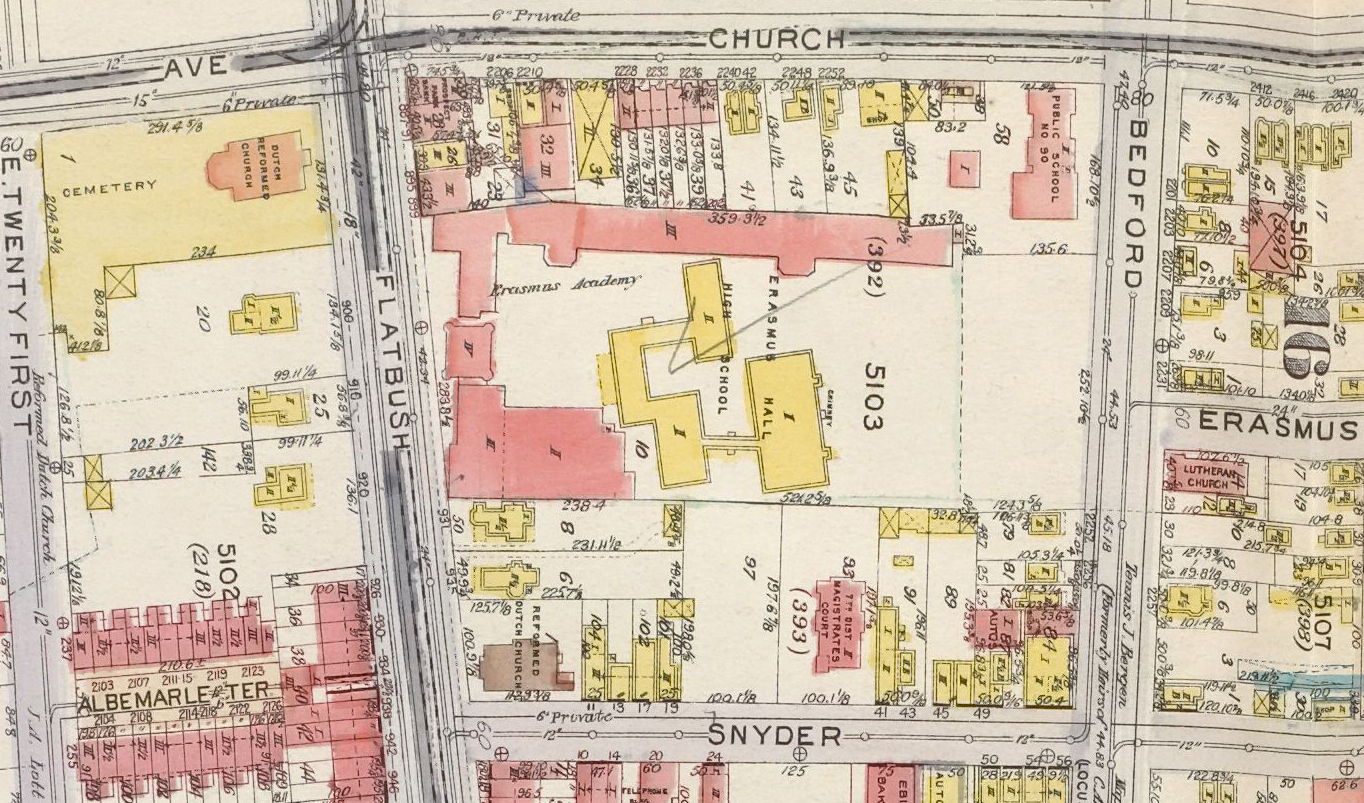

The Board of Education owned a large plot of land located on the northern end of the square block of Flatbush, Snyder, Bedford, and Church. They already had to build temporary classroom buildings on some of it. The new school was designed in the shape of an enclosed quadrangle built on the perimeter of the large lot. Part of the genius of Snyder’s overall design was the decision to leave the 1786 clapboard school in the enclosed green, so that students could still have classes there while the new building was under construction. It is hard to imagine trying to teach and learn with construction and noise all around, though.

The school quad is a collection of separate but connected three- and four-story buildings. With an address of 911 Flatbush Avenue, the complex spans the entire block between Flatbush and Bedford and is longer than it is wide. Construction of each section was staggered, allowing for the availability of funds and the needs of the institution. Each separate building was designed with carefully delineated functions in each connected wing.

The school was built in four stages, two of which were designed by Snyder. The others were designed by his successors, William Gompert (with Snyder) and Eric Kibbon. The later designs fit into Snyder’s quad seamlessly, although with less detail. The dates are 1905-6, 1909-11, 1924-25 and 1939-40. The first building and the tower along Flatbush Avenue serve as the entrance to the complex. The large arched and gated Tudor entrance provides the campus with a center entrance on Flatbush, but also cuts the noise on what was even then becoming a busy commercial street.

Gothic style and Tiffany windows

The school is constructed with buff brick and limestone and features Tudor-arched doorways, Gothic-style windows, a central tower with stone finials, and castle-like crenellation at the roofline. A plethora of stone and terra-cotta ornamentation has a scholastic theme. There are lots of owls.

The interior is also quite fine. The school’s library is two stories tall with large arched window with stained-glass details. It could easily be a study room at an Ivy League college. There are also some beautiful education-themed stained-glass panels and a magnificent Tiffany window with a center panel. It depicts the personification of knowledge flanked by two simpler windows, all in shades of green and blue, using the Tiffany studio’s signature opalescent glass.

There’s also a huge stained-glass window in the school’s auditorium that may be even more impressive. The auditorium itself resembled a great opera house, with a wraparound balcony held up by columns and Tudor arches, and a vaulted and coffered ceiling. Located behind the stage curtain at the back of the stage is the huge window featuring 21 stained-glass panels, each of which depicts some aspect of the life of the school’s namesake, Erasmus. The panels are topped by Gothic tracery and more decorative stained glass. You’re not going to see this in your average high school.

Did I mention there’s also a pool?

The school may have resembled a medieval Gothic institution, but it was constructed with very modern materials and engineering. Underneath the Gothic facade is steel skeleton frame construction. Not only was it more economical, but it was practical. The framing allowed larger and more numerous windows, which allowed fresh air and light into the buildings. Snyder utilized terra-cotta blocks in floor construction for fire prevention and developed new methods of air circulation.

Synder was not just interested in creating beautiful buildings, he had a lifelong interest in education itself and how schools functioned in society. His schools were aspirational. They were part of the assimilation process that introduced immigrant students, and by extension their parents, to America. How it must have felt for them to enter through the grand gates of any of his schools, seeing the beauty, detail, and fine construction created for them in a public school that welcomed all. America was indeed a land of riches and students could aspire to greater heights if they stayed in school and learned. Students lived not only nearby but came from other Brooklyn neighborhoods as well as Manhattan.

As the 20th century progressed, this Flatbush high school produced more graduates who went on to fame and fortune in the arts, sciences, sports, academia, and government than perhaps any other city school. Famous alumni include Clara Bow, Neil Diamond, Mae West, Beverly Sills, Stephanie Mills, Mickey Spillane, Clive Davis, Mort Drucker, Earl G. Graves, Elaine de Kooning, Barbra Streisand, and Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, the first Chinese woman in the U.S. to earn a PhD in Economics, and a well-known figure in the suffrage movement. There were, of course many, many more.

Like many city schools, the latter part of the 20th century saw a decline in academic standards, and the school was broken up into smaller, separate entities in 1994. Today, there are five separate high schools in this massive building under the name Erasmus Hall Educational Campus. They have separate administrations and teachers and hold classes in different parts of the complex. They do share the lunchroom, gymnasium, library, and auditorium, but at different times of the day.

The schools are the Academy for College Preparation and Career Exploration: A College Board School; the Academy of Hospitality and Tourism; the High School for Service & Learning at Erasmus; the High School for Youth and Community Development at Erasmus; and the Science, Technology and Research Early College High School/Middle School at Erasmus.

Large rooms were subdivided to accommodate the separate entities, including the library that holds the Tiffany window, which now has dividing walls that obscure a total view. Unfortunate, but at least it’s still there. The school’s swimming pool, which was built in the 1920s, had deteriorated so much that it was closed for several years. It was important to the community as well as to students, and after a million-dollar-plus renovation, it reopened in 2001.

Crumbling clapboard restored

So what happened to the wood framed Erasmus Hall Academy building? It still stands in the courtyard. The added wings had to be removed for the 1939 additions and the main building was moved out of the way and placed in its current location. The work was done by the WPA, but everything stopped for World War II, and did not start again until after the war. It was used as an administration office and as a museum. One of the first structures to be landmarked after the 1965 passage of the NYC Landmarks Law, Erasmus Hall Academy was designated in 1966.

The following years were hard on the building, so much so that it was closed and allowed to just sit there. The paint was fading, the roof was leaking, the shutters were falling off, and it was home to a clowder of feral cats that entered through broken windows. The landmarked building looked like a candidate for eventual demolition by neglect. Since it couldn’t be used for classrooms or any other school function, the Board of Ed did not want to put any money into upkeep or repair, even though it’s one of the most important 18th century buildings left in the city and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The abandoned building still contained exhibit cases with quill pens and other artifacts from its museum days. By 2017, it had been closed for over 10 years and was in rough shape. There were numerous attempts to find new uses for the building and spark repairs and restoration, but all efforts were rebuffed. Alumni of the school organized vigorously and appealed to the New York Landmarks Conservancy, which paid for condition surveys, and both put pressure on the mayor’s office and the Board of Education to save it.

It wasn’t until then-Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams was able to secure funding that positive steps were taken. The Conservancy, working with the Division of School Facilities, embarked on a restoration plan, working in two phases. The first phase replaced the chimneys, roof, and gutters. The second phase reconstructed the front and back porches, eliminated the shutters, repaired the windows and clapboard, and painted the exterior.

Phase 1 kicked off with $675,000 in funds. More money was obtained by the alumni and other sources to complete the facade repairs, which were revealed in 2019. The completed renovation highlights the building’s elegant Georgian lines, quoins, dentil moldings, restored 12-over-12 windows, and other architectural details. The state of the interior and present use of the building are unknown. Today, one can look through the iron gate and see the 18th century school building, a unique feature in an educational complex that has been preparing students for life and work since 1787.

Related Stories

- Decorator William Payne and His Collection of Colonial-Era Lefferts Houses

- Our Beautiful Brooklyn Blocks

- How Innovator Robert Gair Built an Empire of Boxes in Dumbo

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

I was a student at Erasmus 1971-1973. The original building was the guidance counselor’s offices. Mr. Israel was principal in 1971 and Mrs. Oxman took of in 1972. Mr. Pollack was my guidance counselor and once of the assistant principal’s. The pool was closed when I went there. Recently I have run into some former classmates (but the school was so large we did not know each other when there).

Thank you for sharing your memories!