Shaken by Recent Decisions, Preservationists Say Landmarks Commission Is Not Doing Its Job

Recent decisions by the Landmarks Preservation Commission have caused members of the preservation community to question the agency’s commitment to preserving the architectural heritage of the city.

Recent decisions by the Landmarks Preservation Commission have caused members of the preservation community to question the agency’s commitment to preserving the architectural heritage of the city.

Sources close to the situation say that since Mayor de Blasio appointed Meenakshi Srinivasan as the chair of the LPC in 2014, what constitutes historic preservation within the commission has changed. The LPC has allowed major alterations to landmarked structures, including additions and extensions you can see from the street, under what some claim is a less rigorous standard and with more frequency.

“The LPC has become increasingly permissive in recent years in terms of the size, scale, and design of new construction and additions they will allow in historic districts and on individually landmarked sites,” said Andrew Berman, the executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. “They are more willing than ever to approve larger buildings and additions, and ones which are non-contextual in design.”

Some believe that these modifications to the approval process are emanating from the mayor’s office.

“I think this commission is laboring under some fairly hostile environmental conditions and that doesn’t make it easy on them,” said Simeon Bankoff, the executive director of preservation nonprofit Historic Districts Council.

Those hostile conditions involve what many see as Mayor Bill de Blasio’s courting of developers — despite some initial anti-development campaign rhetoric — partly under the guise of his stated promise to bring 200,000 affordable homes to New York City before 2022.

“This is complicated by an active and rapacious real estate development market which reflexively brindles at regulation,” Bankoff adds. “This creates a very pro-development climate for the LPC to work in.”

And as the city continues to grow and neighborhoods are under constant threat of redevelopment, these changes bring into focus the nature of historic preservation — what does it mean to preserve or landmark if a building can be altered? And what are the implications for the future of historic districts?

“The whole point of historic district/landmark designations is to preserve and protect the special historic character of an area,” said Berman, echoing a familiar sentiment. “When large, out-of-context new buildings and additions are allowed in such areas, that special character and those special qualities are diminished.”

When Dan Houser, the creator of the popular Grand Theft Auto video game, purchased the Brooklyn Heights home where the writer Truman Capote once lived at 70 Willow Street, the initial proposal that went in front of the LPC in 2015 called for a number of alterations, including demolishing the existing rear porch.

At first, this was not approved. But it wasn’t denied either. No action was taken, which invited the proposal to come in front of the commission again. On the second time around, the plan was approved with only small changes — a pattern that many contend is part of the current problem. The historic porch, a point of contention, was allowed to be removed.

Some believe that, under the guise of “no action” decisions, the LPC is merely presenting a false formality. According to one preservationist who wished not to be named, developers are aware that a “no action” means they are on the right track. In the past, many of these “no action” decisions would be denied, or the LPC would require substantial changes before approval was granted.

Then there are changes made under the guise of adaptive reuse, many of which have well-regarded architects behind them and tend to breeze through the approval process.

When it came to what was then the Brooklyn Heights Cinema at 70 Henry Street, the longtime owner hoped to demolish the 19th century one-story commercial structure and build a five-story building with condos above the cinema, but the proposal went before the LPC twice and seemed to be stalled, with no action taken. In 2014, he sold the building to developers Madison Estates and JMH Development. In 2015, under new leadership, the LPC approved a new design by architect Morris Adjmi that added three stories of condos to the existing one-story building.

While preservationists argued that the former movie theater should be saved, Randy Gerner, the architect for the longtime owner told DNAinfo that because the one-time butcher shop had been renovated numerous times since it was built, it had lost a fair amount of its historical significance.

At the LPC’s public hearing on June 16, 2016, Judy Stanton of the Brooklyn Heights Association argued that the building’s “surviving historic bones” would be overshadowed by the new construction on top. “Blended too seamlessly into the new structure as a base, the old building would essentially disappear,” she said.

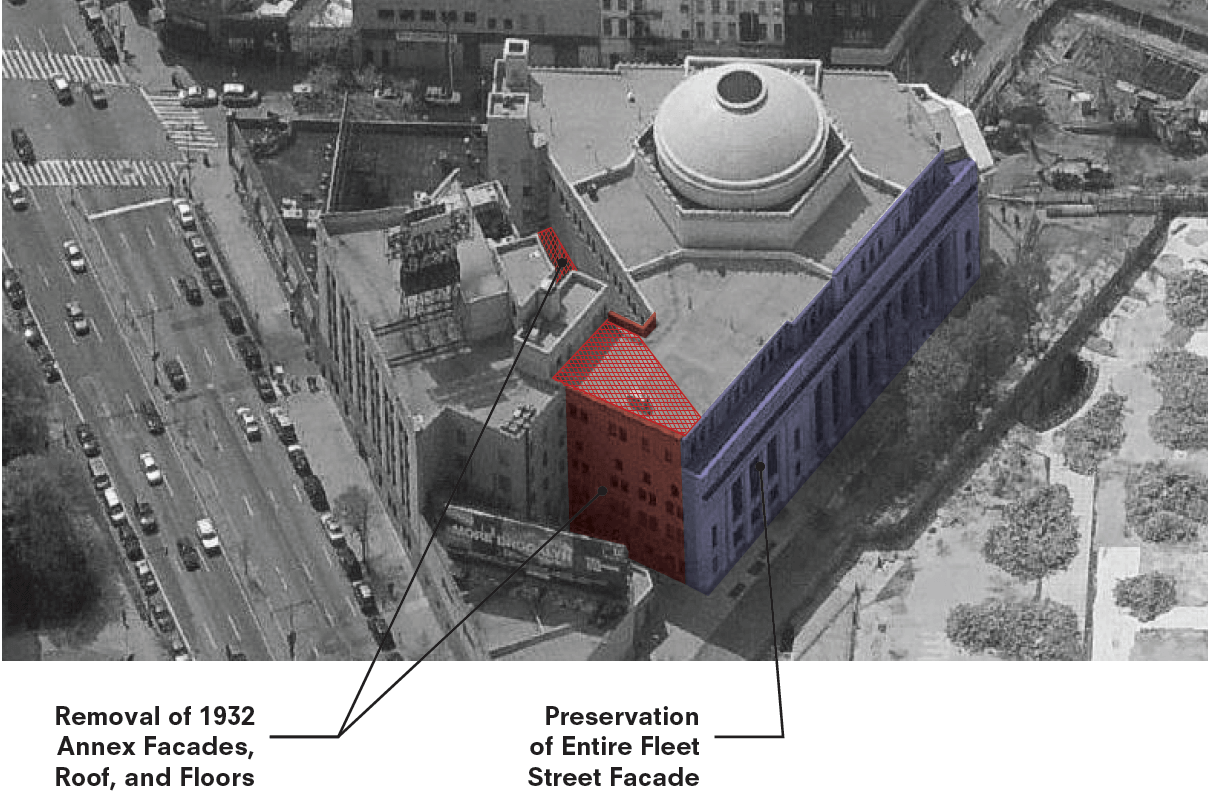

Similar examples can be found elsewhere: at the former Arbuckle Brothers Sugar Refinery at 10 Jay Street, where, after requesting some minor changes, the LPC approved a striking and controversial ODA-designed crystalline facade for a restoration of the 19th century factory in 2015, and at the landmarked Dime Savings Bank building in Downtown Brooklyn, which the LPC allowed to be structurally connected to the borough’s future tallest tower at 9 Dekalb Avenue, calling the proposal “flawless.” The Domino Sugar Refinery at 292 Kent will lose its roof and innards to accommodate a glass-walled building inside the original structure, turning it into a “ruin,” in the testimony of one dissenting commission member, to adapt it as an office building.

The more these type of proposals are approved, it sets a precedent moving forward for developers to propose more egregious changes to landmarked structures, according to some.

“The LPC won’t designate buildings because they are too altered, but will allow alterations to buildings that are designated,” said a preservationist who wished not to be named.

In Manhattan, there is the Robert and Anne Dickey House at 67 Greenwich Street, built circa 1810 and the only remaining house of what was once a fashionable residential neighborhood. It was considered for designation in the 1960s but designated as an individual landmark only in 2005.

Just last year, the LPC voted to grant a Certificate of Appropriateness to remove a non-historic rear addition and incorporate the building into a new mixed-use 35-story tower to be built adjoining it.

In the Meatpacking District, plans to construct a new 111-foot-high building at 70-74 Gansevoort Street, went in front of the LPC twice with very minimal changes before being approved, despite significant opposition from local advocates. Critics of the move say the scale of the approved proposal disregards the area’s designation report in favor of new development, no matter what the cost.

In the above cases and elsewhere, the LPC seems to evaluate proposals more on architectural merit than preservation merit, according to one observer. “This has resulted in some wonderful and exciting designs, especially in Brooklyn, but I worry about the implications for preservation,” she said.

For example, the designs at 10 Jay Street, Domino, and 9 Dekalb are thoughtful, innovative, distinctive, and seem to be about more than just the biggest bang for the developer buck. And like many of the proposals that come before the commission, they make an effort to relate to surrounding context and history.

When SHoP Architects revealed its design for the supertall at 9 Dekalb, they claimed they were using materials — white marble, crystal gray vision glass, bronzed metal and blackened stainless steel — inspired in part by the bank’s origins, and made strides to not alter views of the bank’s iconic dome. While these kinds of comments have become standard practice for architects proposing similar types of projects before the LPC, the commission quickly approved the design, calling it “enlightened urbanism at its best,” and said it “improved the vision of this historic landmark.”

At the same time, some sources claim that this kind of response represents the LPC kowtowing to well-known architects and developers at the disservice of the preservation.

In response to preservationists’ concerns, LPC Director of Communications Zodet Negron emailed Brownstoner this statement: “Historically, the Landmarks Preservation Commission has allowed for new development and contemporary designs, as well as rooftop and rear yard additions. That has not changed. In regulating landmark properties, the commission’s mandate is to ensure any proposed changes are compatible with the scale and character of the buildings or historic districts, not to prevent changes. All applications that come before the commission are considered within this context.”

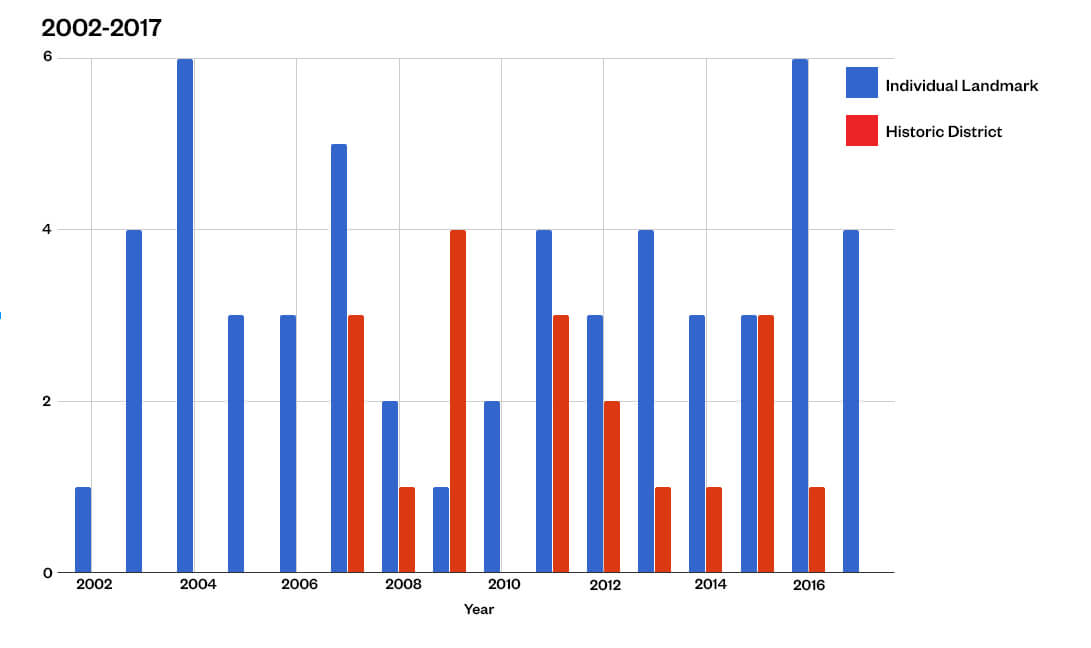

But at least in Brooklyn, the number of individual landmarks that have been designated is on the rise. Between 2002 and 2013, when Robert B. Tierney was the chair of the LPC under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the commission designated 24 individual landmarks in the borough.

In the four years since Srinivasan became the chair, they have already reached almost half that number, with 16 individual designations in Brooklyn. As for historic districts, five have been designated in the last four years, which puts them roughly on track to meet the 14 that were designated under Tierney. The clearing of the backlog — a major feature of Srinivasan’s tenure — boosted the numbers, with eight structures designated as a result.

Some of the important landmarks in Brooklyn under the current administration include the Chester Court Historic District in Prospect Lefferts Gardens, the Huberty House at 1019 Bushwick Avenue in Bushwick, the Bedford Historic District Extension in Bed Stuy, St. Barbara’s Church in Bushwick and the Forman Building in Williamsburg.

In December, East New York received its first designation in 36 years with the Empire State Dairy complex at 2840 Atlantic Avenue.

Yet, as positive as these developments are, some LPC watchers say they don’t alter the pro-development environment, whereas others say they are a smokescreen to cover up a pro-development agenda.

“The landmarks law depends a great deal upon the expertise and judgment of the commission to faithfully carry out the mission of preserving and protecting New York City’s special architectural and cultural heritage and history,” Berman said. “That is obviously open to a certain degree of subjective interpretation, so that independent, impartial experts can decide what that means and the best way to carry it out. But if that charge is being interpreted laxly or overly broadly, it makes the landmarks law increasingly toothless and meaningless.”

Related Stories

- Preservationists Thrilled East New York’s Empire State Dairy Landmarked, Say More Needs Saving

- Montague Street Row House Looking for a History-Inspired Makeover

- Brooklyn Treasures St. Barbara’s Church and Forman Building Are Now Landmarks

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment