From Pakistan to Brooklyn: A Quick History of the Bathroom

Topped only by the kitchen, the bathroom is one of the most important and frequently renovated rooms in any house or apartment.

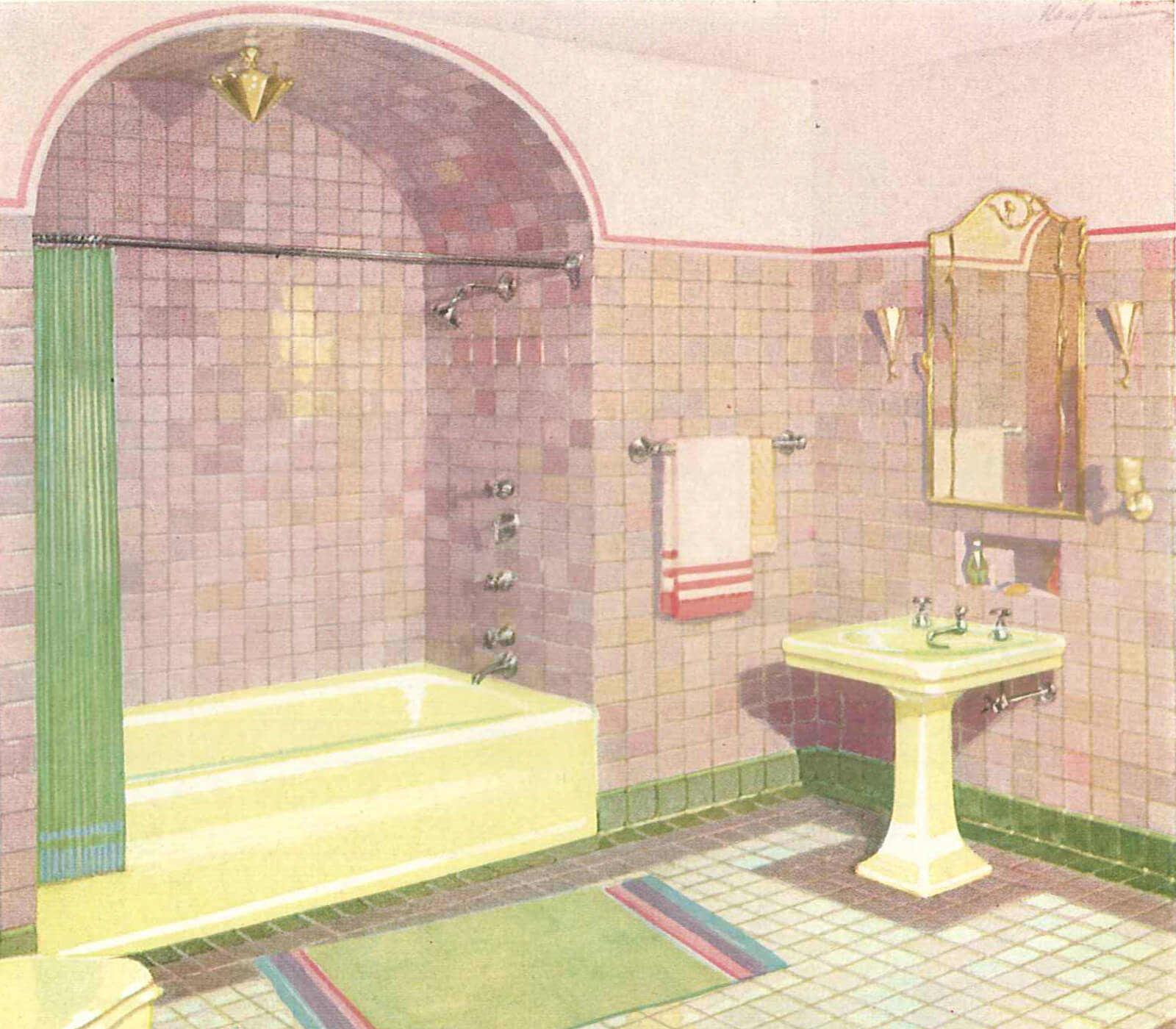

1940s bathroom. Illustration via American Standard Plumbing Fixtures Catalogue

Editor’s note: This is an update of a series that ran in 2012. Read the originals here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5.

Topped only by the kitchen, the bathroom is one of the most important, and therefore most installed or renovated rooms in any house or apartment. Twenty-first-century Americans LOVE their bathrooms. We love them so much, we want to have lots of them. Full baths, half baths, powder rooms, en suite baths, master baths, steam rooms and saunas.

It’s rather amazing to realize plumbed bathrooms with toilets existed in the ancient world. Incredibly, the bathroom did not return until the 1850s.

Before the Bathroom

The need for personal cleanliness knows only the limits of space and cash. Most of us know about the famous Roman baths, so we know this obsession goes way back.

Early man first visited the bushes, and then took himself to the river to clean up. So from the first, we really have two hygienic functions to talk about in the bathroom, and they weren’t joined together for a long time. The first bathtub was a body of water, with man/woman first splashing to get clean, and then discovering the ability to swim.

There is not a culture on earth that does not value being clean, however they have to go about achieving that. Cleanliness is both a physical and spiritual state, so the first known bathtub or basin was a ritual pool where people cleansed themselves before worshipping, getting both their bodies and spirits clean.

By the third millennium, B.C., man had invented indoor plumbing for both bathing and sanitation. Remains of ancient toilets and sewers show up in the ruins of ancient cities in the Indus Valley, in what is now Pakistan, dating from 2800 B.C. Drains removed wastes to cesspits or drainage systems.

These same cities also had bathing rooms, which drained through pipes in the walls to a municipal drainage system. Indoor plumbing. Ancient toilets can be found in the ruins of Rome and her colonies.

The earliest known bathtub was found in Greece, and was found in the Palace of Knossos, in Crete, dating from 1700 B.C. Excavations of Greek cities have turned up alabaster and ceramic tubs, as well as sophisticated hot and cold water systems providing indoor plumbing to the bathers. We are more familiar with ancient Roman baths, where bathing took on great societal and public importance.

Wealthy Romans often had private baths, but the grand public thermal baths were not only a place to get clean, but were also social gathering spots, where friends gathered, meetings and business deals took place, and entertainments were enjoyed. Today, especially via Hollywood, we find the Roman baths salacious and carnal, but for them, it was an important societal function and ritual. It wasn’t the bath that brought Rome down.

The bath was equally important to the societies of the Middle East, with ritual bathing, the mikveh, an important part of Jewish culture. Such baths were found in the ruins of Masada. The traditions of the hammam, or “Turkish bath” is equally well known throughout all of the Arab world, giving rise to bathing chambers of great beauty, admired to this day.

And in the East, the steam baths of Japan have been in use almost as long as the baths of the ancient Western World. Everyone loves a good bath.

That didn’t change for many centuries in the West. Although we like to think that the people of the Middle Ages were as filthy as the pigs the peasants kept, evidence has shown that they loved a good bath, as well. Bathing was encouraged by Gregory the Great, the first monk to become pope.

Medieval royalty was encouraged to wash up daily, wash their hair and hands, and clean their mouths and teeth. Scholars tell us that the wealthier classes in Europe often bathed together, sometimes in the old Roman baths left behind after the fall.

They stayed in the baths, soaking while eating and being entertained. Men usually left their hats on, and women kept their jewelry and headgear on, a veil on a woman indicating her status as a married woman.

Of course, there were certainly the moralists and those who screamed “sin” and hedonism at the whole affair. Depending on where you were, or who you were, bathing in the Middle Ages could be enjoyed or condemned, and as time went on, public bathing, especially in mixed company, was seen more and more as a prelude to sinful behavior, and the bath came indoors, or stopped altogether.

Some towns in Eastern Europe passed laws enforcing a bath at least once a week. If one did not, he had to pay a fine. Yet other populations could go for years without bathing, especially the poor and those in colder countries.

Bathing in winter became very suspect, as steam baths were seen as a source of contagion. As plague ravaged the lands, public bathing stopped, as people thought that bathing with others would cause the plague to enter through “miasmas” of steamy hot water. This continued throughout the Renaissance. As time passed, steam baths, if possible, replaced soaking baths, and for the wealthy, perfume became the bath of choice.

Most of the public baths at this time were shallow rectangular pools, often side by side, where bathers sat and soaked, often eating, reading, or playing board games. A more portable bath was usually wood, similar to a Japanese soaking bath, or in the manner of a wine cask, with wood held together by metal staves, made waterproof with pitch, and usually lined with a cotton or linen cloth.

These baths would be filled with water heated on a separate fire, poured by servants or family members. Depending on social status and local custom, women would bath nude, or in thin chemise dresses. Men would also take care to cover their privates.

Throughout histories and cultures, herbs, flowers, salts and scented oils were used to make baths more fragrant, and help clean the body. Soap was in use by the Romans, the Gauls, and the Celts, but took a hiatus for several centuries, and did not appear in Europe again until the Middle Ages, centering in Marseilles, then Genoa and Venice.

Most Eastern and Central European countries didn’t see soap again until the 1500s. Soap at this time was made with animal fats, lye, and ashes and could peel flesh. Scented soaps did not appear until the 16th and 17th centuries, and the formulas and recipes for fine scented soaps were a well-guarded trade secret, keeping prices up, so that these mild hand and face soaps were the property of only the rich.

Bathing (or not) is only half the equation in the bathroom. Eliminating waste is the other half. Depending on where one lived and his or her station in life, this necessary function was either a nasty problem to solve or a veritable goldmine.

Urine has long been used as a tanning agent for leather, and in the production of saltpeter, a component of gunpowder. People had businesses, going about collecting from wherever animals and man relieved themselves, storing it and selling it. It could be quite lucrative, although never very socially acceptable. There was good reason leather tanners were usually banished to the outskirts of town.

Night soil, however, did not have very much resale value. Meat eaters like humans don’t produce good fertilizer. So from the very beginning of civilization, there have always been those whose job it was to collect and cart waste somewhere else.

Most medieval castles or wealthier homes had garderobes; privy rooms in closets, where waste materials fell into a pit or midden, or worse, into a body of water. People who didn’t have these rooms often dumped their waste from the chamber pot into the streets.

It’s a wonder they didn’t all die of plague, and but for the night-soil men, they might have. These individuals cleaned both animal and human waste from the streets, alleys, middens, sewers and trenches, and carted it out of town. Far out of town. Outside of London, one pile o’ poo was seven and a half acres wide, and was called “Mount Pleasant.”

As time went on through the centuries, the aristocracy in Europe began to once again embrace the bathtub. We find elaborate and costly tubs carved out of all kinds of stone in the palaces, country homes and city mansions of royalty and the gentry.

Very chic, and very hedonistic and naughty! By the 17th century, when Europeans began settling in North America in large numbers, the bathtub for your average home was a portable tub made of wood, lined with steel. It was brought out before the fire and hearth, and filled with heated water.

The whole family would take turns bathing in the same water, which would only then be dumped. This was usually a once a week affair, usually Saturday night, and everyone had a bath, if they needed one or not.

The homes of this time had privies in the back yard. By the beginning of the 19th century, when homes were being built in Brooklyn Heights, Greenwich Village, and the other early settlements of New York City, there were no bathrooms in these houses.

There was the tub stored in the pantry, and a chamber pot under every bed, and the privy out back. This would not change until the dawn of the miracle of indoor plumbing, in the 1850s.

The Beginnings of the Bathroom

Before the 1850s, the three parts of the bathroom were in separate rooms. If you needed to wash up, splash some water on your face or hands, or sponge clean yourself, you needed only a basin and a container of water, preferably heated.

If you were middle-class or wealthy, you had a wash basin or washstand in the bedroom. Otherwise, it was probably the family basin in the kitchen. When you wanted to take a bath, a portable tub was carried out in front of the fire, water was heated, and you took a bath.

The rich may have had the luxury of a tub in one’s chambers, but for most people, that infrequent bath took place in the kitchen by the hearth. Houses had privies out back.

By the mid-1800s, the connection between waste and health had finally been made, and the great municipalities of the world — London, Paris, New York — began to build elaborate sewer systems to flush the wastes from the city.

With knowledge comes technology, and it was the great technological advances of the industrial age that both supplied the problem — too many people and too much waste in a relatively small space — with the solution: modern plumbing and the flush toilet.

The first flush toilet was actually invented by Queen Elizabeth I’s godson, John Harrington, way back in 1596. It was seen as a great novelty, but it didn’t catch on. One can just imagine the Queen and a bunch of courtiers standing around flushing and watching what happens, like 5-year-olds. Or a cat. But there was no system of pipes or pressurized water, so not all that much happened.

In 1775, the first patent for the flush toilet was awarded to British inventor Alexander Cumming. He and another inventor, Samuel Prosser, in 1777, made great strides in figuring out the modern toilet. But there still wasn’t really any way to hook it up to a water source, or a waste-pipe system.

By this time, another slang word for the toilet had been coined: the water closet, so called because early indoor privies, really fine furniture pieces made of wood, were often put under the stairs, in a closet.

The first flush toilets in the U.S. were in hotels. In 1829, the Tremont Hotel in Boston was the first hotel to have indoor plumbing, with eight water closets built by architect Isaiah Rogers.

They were on the ground floor of the hotel, and were powered by a water storage system on the roof, gravity fed to flush the toilets into a sewer system. It was simple, but it worked. There was still the problem of the back flow of sewer gases and methane to take care of. This would take a few more years, but the idea of the modern toilet was almost here.

In 1834, Rogers surpassed himself by designing the Astor House, in Manhattan, a large six story building (no elevators yet) with 17 bathrooms on the top floors which served 300 guests. In addition to water closets, baths with running water were also available.

These bathtubs had little gas furnaces and tanks attached to the side, or above, which would heat the water. Both the W.C. and the bath drained into the sewer system, and were filled by huge water tanks on the roof. Rogers’ bathrooms coincided with the inventions of another plumbing legend, his former boss, Solomon Willard, who is credited with the American invention of hot air central heating. The two features would come together 50 years later in the late Victorian bathroom.

Finally, someone figured out how to deliver pressurized water that had sufficient power to flush wastes into a system of pipes that led outside of the house, to the sewer. Englishman Thomas Crapper usually gets the credit for this, but he did not invent the modern toilet.

Thomas Twyford actually holds that honor. In 1885 he invented a valveless toilet made out of vitreous china. Previous models had been made of wood and metal. Thomas Crapper owned a plumbing supply company, and he bought a patent for a “Silent Valveless Water Waste Preventer,” and began making toilets. The rest is history. As we know, the slang phrase “in the crapper” comes from his name.

It was brought to the United States by American soldiers after World War I, after seeing Crapper’s name all over toilets in the U.K. If Thomas Twyford had stamped his name all over every other toilet in England, we might be saying “in the twyford.” Doesn’t have the same ring.

None of this would have been possible had engineers and inventors not come up with modern plumbing. Ancient Greeks, Egyptians, Romans, Japanese and East Indian cultures had all managed to come up with plumbing systems, but much of the knowledge of those inventions was lost.

The first pipes in America were wood. They were bored out elm or hemlock tree trunks, joined together with pitch. The first piped water in Boston was a system of wooden pipes leading from Jamaica Pond to Boston Harbor. Wooden pipes were used until the early 1800s, when cast iron pipe was developed.

Even today, on occasion, remains of the wooden pipes are still dug up in city excavations. Philadelphia was the first American city to develop and use a system of cast iron pipes, drawing power from windmills to force water through the system.

New York City also had an early wooden pipe system, and switched to cast iron in the early 1800s. After the disastrous fire of 1835, which showed the inadequacies of the system, New York developed the huge mains of the Croton Aqueduct System, developed in 1834 to pump water into the city and to smaller reservoirs at 42nd Street and at Central Park, from the reservoir at Croton, N.Y.

In 1857, engineer Julius Adams revamped Brooklyn’s water system, creating the first modern city sewage system, and in the process, developing formulas for determining sewage needs for a growing city. He made modern sanitary engineering possible.

He also printed his findings, providing the blueprint for towns and cities across the country. While this was going on, a group of men in the growing profession of engineer/plumbers were figuring out the correct way to vent sewer gases up out of homes. They figured out standards in waste pipes and drains. Through trial and error, they figured out angles, size of pipes needed and other details for plumbing the modern city home. Fittings, valves and fixtures were figured out.

Manufacturers on both sides of the Atlantic worked out the details of the toilet, its shape, size and materials. Vitreous china became the preferred material, perfect for both cleanliness and possibilities of pleasing design. They also worked out details in sinks and bathtubs and the fixtures that would deliver the water. Everything was finally coming together for the indoor bathroom, and by the height of the High Victorian Age, it was all in place. Let the spending and the decorating begin!

The Victorian Bathroom

Like a cosmic event where all of the stars and planets line up, the phenomenon that we know as the modern bathroom all came together in the late 1800s: The city sewer systems, central heating, hot and cold running water, the perfection of indoor plumbing and pipes, the invention of the flush toilet, the invention of the stationary bathtub and sink, the realization that all of these things could best be utilized in one room, and new social programs promoting personal cleanliness and hygiene gave us the bathroom.

And what bathrooms they were! When the Victorians got an idea right, they ran with it. Money and manufacturing was easy to come by, and soon hundreds of companies were turning out all kinds of things for the new bathrooms.

Necessity was indeed the mother of invention here, and as the idea of an indoor bathroom became not just a novelty for the rich, but a necessity for everyone, new innovations and inventions were coming fast and furious. New companies, many of which are still in business, started in the second half of the 1800s.

Take Kohler, for example, one of the largest makers of toilets, tubs and sinks. They started in 1873, when an Austrian immigrant named John Michael Kohler bought the Sheboygan Union Iron and Steam Foundry.

They were making farm implements and castings for ornamental fencing, urns and cemetery crosses. In 1883, Kohler had the idea to bake an enamel coating to one of his horse trough/pig scalders, and the first Kohler bathtub was born. They never looked back.

The Standard Sanitary Manufacturing Company, founded in 1875, was a small company making plumbing fixtures. In 1899, they merged with several other similar companies, and became the foremost makers of plumbing fixtures, bringing such new innovations such as hot and cold water mixers, the one piece toilet, and corrosion-free bath plumbing fittings.

By 1929, they were the largest maker of bathroom fixtures. They became American Standard in 1967, after a merger with the American Radiator Company.

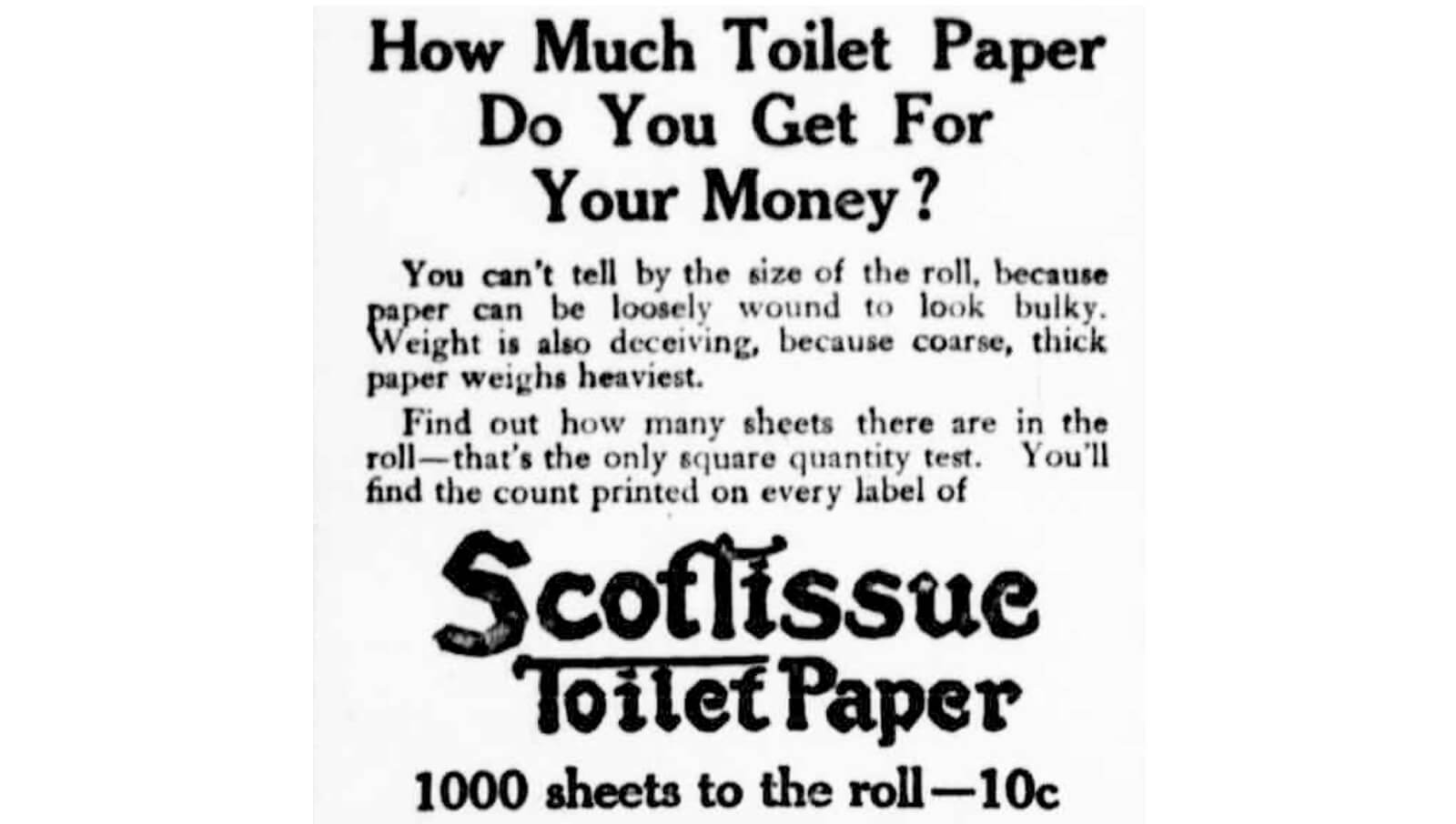

In 1857, New Yorker Joseph Gayetty produced the first packaged toilet paper. It was called “The Therapeutic Paper”, and had aloe mixed into the paper mixture. It was not on a roll, but stacked sheets folded in a box, and each sheet had Joseph Gayetty’s name printed on it.

In 1890, Scott Tissue came out with the first toilet tissue paper on a roll. They had a hard time selling it, as it was an “unmentionable” that couldn’t be advertised. Chemists sold it by bringing it up from under the counter, as people were too embarrassed to ask for it, or be seen picking it up from the shelves. They sold both small rolls, and folded tissues. As far forward as 1935, Northern Tissue advertised its tissues as “splinter-free.” Ouch.

There were many more success stories, all making money from the bathroom. There were the people who invented the white toilet seat, a wood frame coated in hard rubber, a change from the natural wooden seat of old.

This was in 1904. Another company, the Olsenite Company, was in the plastics business, manufacturing steering wheels for vehicles. Right around World War II, they came up with a coating process that used plastic instead of rubber, and they became one of the first companies to make plastic toilet seats.

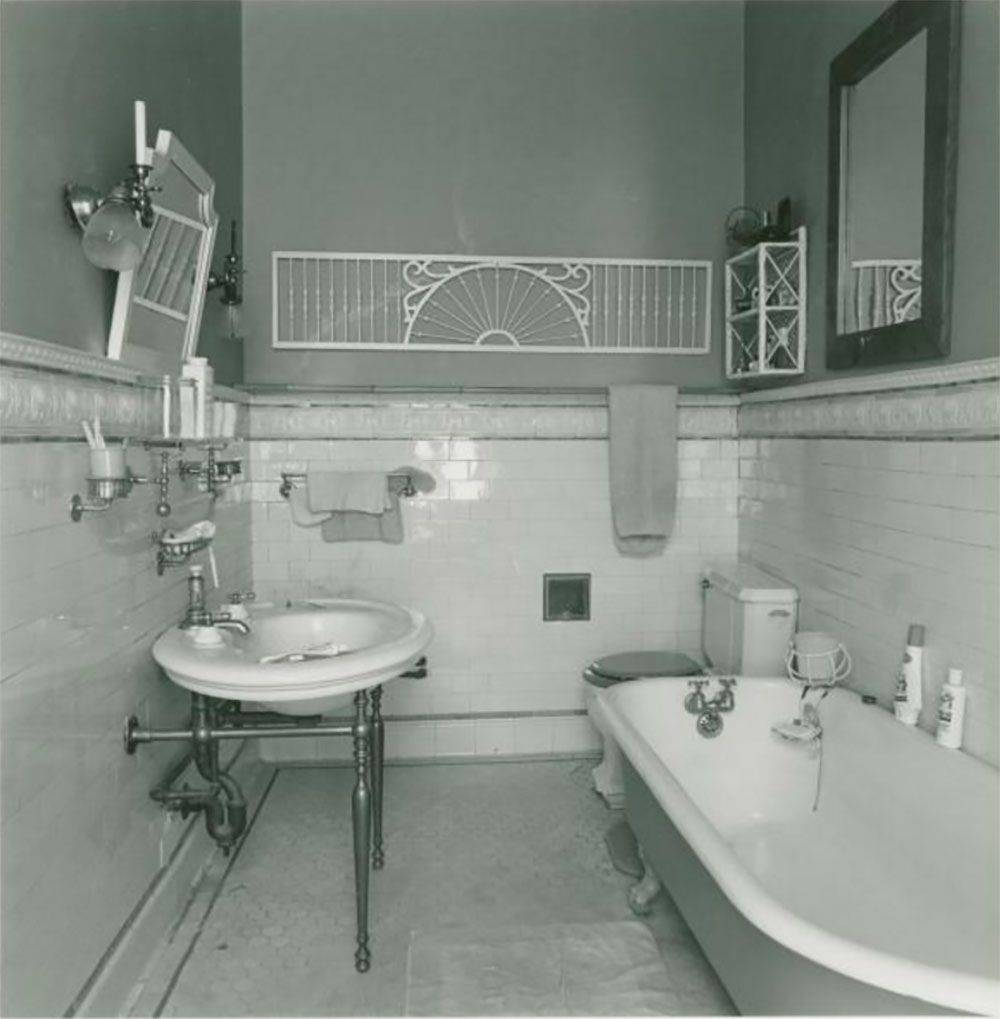

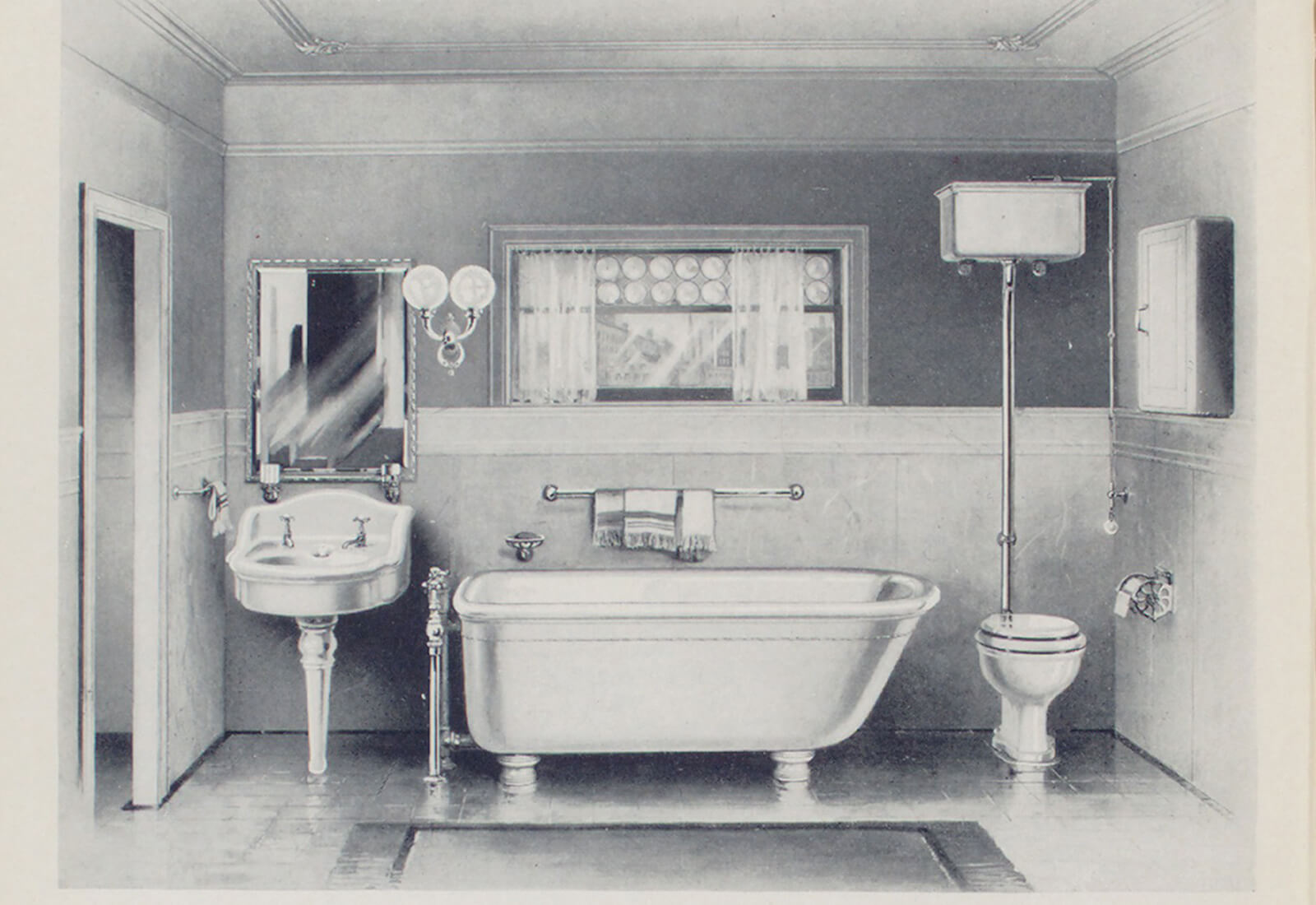

For many old house lovers, the Victorian bathroom is the quintessential bathroom, bar none. There aren’t too many period photographs of actual bathrooms from the Victorian era, because it was seen as terribly gauche and unrefined to take pictures of this room. But lots of examples remain in our homes, and manufacturers of bathroom fixtures and features had illustrations galore in their catalogues, and from them we can get a lot of information.

Let’s talk about the room itself. In wealthier homes, the toilet was often in a room by itself, in a corner, or an anteroom with a door. This was the ideal, still a water closet, and for many people, then and now, the only way to have a proper bathroom. Unfortunately, that didn’t work out too well with the smaller spaces of our cities. Very few bathrooms in Brooklyn row houses have separate toilet closets.

The room itself was always relegated to the bedroom floor, above the parlor floor, away from the public rooms of the house. Many houses had a servant’s toilet off the kitchen, often outside in a shed, or in an attic. The modern powder room was pretty much unheard of in the beginning.

The bathroom usually had wainscoting made of either tile or bead board. As the Victorian age progressed towards the 20th century, tile became the wall covering of choice, heralding a rage for sanitary-ness, and tile, especially plain white tiles, were the best sanitary materials available, the glazed surfaces perfect for frequent and relatively easy cleaning. So-called “subway tiles,” as well as other size tiles were very popular, and still are.

Often the tiles were matched with decorative bands of colored or embossed tiles in pastel colors, as accents. These can still be found in period brownstone bathrooms today. In the homes of the rich, a combination of tile and white marble was often used, with wall panels of marble, marble sinks, and even marble floors.

The toilet was often on a marble slab, as was the tub. If there was a separate shower cubicle, it could be marble, or tile. In more middle-class homes, unglazed white tile, often hex tiles, or square tiles, sometimes with black accent tiles, was the material of choice for bathroom floors.

If the bathroom did not have tile from ceiling to floor, the walls were usually painted or wallpapered above the chair rail. The ceiling was plastered as well. The Victorians were hyper sensitive about privacy; so many intact Victorian bathrooms have stained glass windows, often really beautiful and intricate ones, for privacy. Opaque patterned glass was the other glass of choice, especially in more modest homes.

The earliest Victorian tubs were not claw-foot tubs, as most people think. They were oval tubs, some with wooden rims, some made of zinc, tin, or copper, and inset into wooden casings. It wasn’t until John Michael Kohler began marketing his enameled pig scalder that the idea of enameled cast iron tubs came about, and Kohler made the first in 1883.

Other manufacturers soon followed, and by 1885, the cast iron claw-foot tub was the tub of choice for the Victorian bathroom. It would last until the 1920s, when the double walled enameled tub became the next new thing.

By that time, there had been many innovations to the claw foot, including the installation of shower heads and shower curtain rods. Half tub enclosures that came up like a clamshell around one end of the tub, with shower heads, had a run of popularity, and today those are rare and highly prized.

The fancy ones in catalogs and illustrations are almost never seen today. They just didn’t survive the constant change for the newest thing.

Bathroom fixture companies came out with all kinds of fancy carved tub enclosures, feet for cast iron tubs, shower enclosures, and all kinds of goodies to make the bathing experience longer and more enjoyable. The days of avoiding a bath were over.

Brooklyn Bathrooms

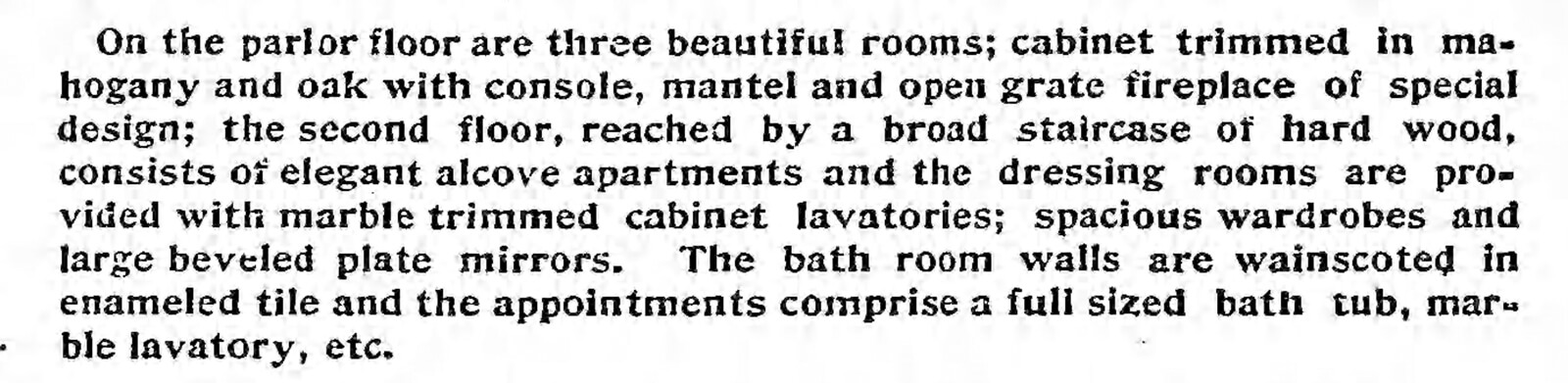

The Brooklyn Eagle ran a large real estate section touting all of the newest neighborhoods and homes that were in development, or for sale, on October 12, 1897. Part of the sales pitch for any property, be it a row house, flats building or stand-alone suburban house, was to talk up the newest in bathroom facilities.

The description of a new row of houses on Bergen Street, between Brooklyn and Kingston avenues, is a good example. Here’s what they said regarding the bathrooms: “The second floor, reached by a broad staircase of hard wood, consists of elegant alcove apartments, and the dressing rooms are provided with marble trimmed cabinet lavatories, spacious wardrobes and large beveled plate mirrors. The bathrooms are wainscoted in marble tile, and the appointments comprise a full sized bath tub, marble lavatory, etc.”

Another ad boasts, “The plumbing is of the most modern, with handsome tile bathrooms.” Yet another ad lists that property’s attributes with “…all lead pipe and exposed nickel plumbing, hard wood trim, tiled bath, extra servant’s bath, dumb waiter, refrigerator, electric lighting with burglar alarm with clock attachment…” The bathroom had arrived.

Full indoor plumbing allowed for not only the bathroom, but the dressing rooms that were built into every single-family row house from the late 1870s on. Most single-family row houses had at least two main bedrooms with two back-to-back dressing rooms between them, accessible through a pocket door between them.

These dressing rooms, as described in the above ad, usually had a built-in sink, often marble clad, around a woodwork base, surrounded by mirrors. Around the sink would be cabinets, wardrobes and often built-in chests of drawers.

Depending on the house, some of these dressing rooms were quite large and spacious, others more utilitarian and sparse. But they all had hot and cold running water. These dressing rooms were invaluable for washing up, as there was only one bathroom in an entire house.

The bathroom itself was a wonder for Victorian eyes. Because it was all so new and impressive, it was important that the workings were seen, hence the copy, “exposed nickel plumbing,” in virtually every ad in the paper.

Unlike today, where we like to hide the workings of everything, from plumbing to electrical cords, the Victorians exposed their pipes. It also made it easier to repair, in case of imperfections in the systems. And there would potentially be a lot to repair.

The upper-class Victorian mindset insisted that there was a tool or an object for every function. This was not because of any kind of expediency, it was because they had money to burn, and companies manufacturing goods figured out that if they made it, it would sell.

And they were right. Take silverware, for instance. Where the Colonial household had a fork, knife and spoon for daily service, the Gilded Age home had at least four or five of each needed for a full course meal. There were dinner forks, luncheon forks, dessert forks, salad forks, fish forks, asparagus forks, pickle forks, olive forks, and on and on, for each utensil.

That doesn’t even include serving utensils, which were even more complicated. One was expected to know which utensil was for what dish, and how and when to use it, and servants were required to know as well, in order to set the table. Woe betides a gauche homeowner who got it wrong.

The well-appointed bathroom was operating from a similar mindset. Manufacturers put out a huge amount of products, each designed to be used for specific purposes. The average brownstone bathroom did not have all of this stuff, but as houses grew more grand, you can often find bathrooms from the late 1880s and after, with a multitude of appliances, in both mansions and upper-class speculative houses.

In addition to a sink, toilet and tub, the deluxe bathroom of the era could have a bidet, a foot bath, or a fancy ribbed shower attachment on the bathtub, or that same ribbed shower apparatus in the separate shower. The bathtubs came in several shapes and sizes, from a child size 3-foot-long tub, to the classic 5-foot-long size, and a highly desirable 6-foot-long model. Plumbing for these tubs included front mounted fixtures, coming out of holes in the top of the tub, as well as front or side mounted fixtures that came out of the floor and hung over the tub.

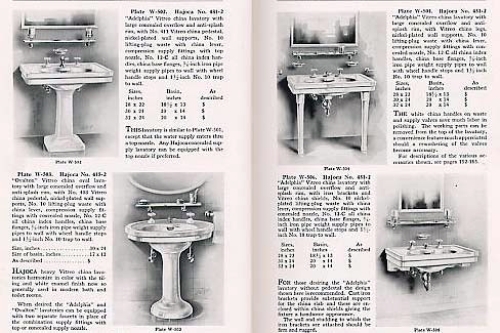

Earlier sinks were usually flat marble tops with a drop-in porcelain sink, in a multitude of sizes. The sink could be plain, or often was decorated with a painted pattern, often floral, baked into the porcelain, just like dishes. Many of these still exist, and can be quite pretty.

The marble tops often had marble back splashes, these also ranging from a few inches high to a huge decorative element. The sinks were wall mounted, with ornate brackets and nickel stands, allowing all of the plumbing to be displayed.

As the 20th century approached, the marble top sink was replaced by a vitreous porcelain sink, in white. These sinks were free standing, or wall mounted, and often hid the plumbing behind a pedestal of some kind. The variety of style and size of these sinks was limited only by one’s wallet and room in the bathroom.

The toilet had also changed. The first toilets depended on a high tank to help gravity drive the water through the system. The tanks, often made of wood, lined in lead or other metal for waterproofing, were attached to the bowl by long pipes.

The bowls were most often plain white vitreous porcelain, but these too, were often decorated with flowers and other decorative motifs. Some very ornate bowls were sculpted with designs and shapes, all of which was fired into the bowl itself.

Today, these bowls are extremely rare and quite expensive, but there are still a few around. Many here in the modern bathroom are European, salvaged there. By the turn of the 20th century, innovations to the flushing system enabled manufacturers to join the tank and the bowl, developing the modern toilet.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the bathroom is as we know it today. So too is the attitude towards cleanliness and privacy. Community is now out. For the middle-class or above, the sanctity of the bathroom was established. Poor people still had to share facilities.

Tenements in our cities were not required to have indoor bathrooms until the early 20th century, and many still had outdoor privies in the back of the buildings. If there was a toilet, there might be one on each floor, shared by several families.

Bathtubs were also not a requirement in each apartment, and many tenements had communal tubs. Even the most “enlightened” tenements, such as Alfred Tredway White’s Riverside Apartments, in Brooklyn Heights, built in 1890, had communal bathing facilities in the basement.

The New Tenement Law of 1901 stated that indoor toilets had to be introduced into all new tenement apartments, as well as bathtubs. Older apartments were supposed to be retrofitted, and toilets and tubs put in. Tubs remained in the kitchen for many years, but at least they were there.

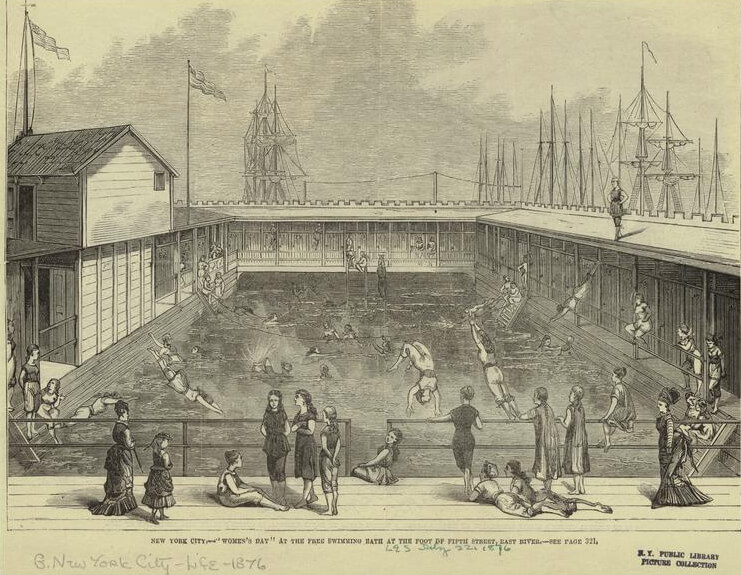

Because sanitary facilities were so bad for poor people, especially when thousands of immigrants flocked to our cities, public baths had been established.

The Bathroom in the 20th Century

By World War I, the bathroom of the average American home looks very similar to the average bathroom in most American homes of today. Every new home was fitted with at least one bathroom. In fact, bathrooms are so cool, many houses opted to have more than one.

The manufacturers of bathroom products such as fixtures, tile, lighting, accessories and plumbing fixtures got creative and gave the customer more variety to choose from for the ideal bathroom.

America became absolutely obsessed with the bathroom. And that continues to this day.

The typical bathroom around this time consisted of a toilet and attached tank, porcelain sink, often wall mounted, and a bathtub with a wall mounted shower attachment. Shower curtains kept the water from pooling on the floor, which was tiled in small black and white hex or square tiles. The walls were also tiled, especially from the chair rail to the floor, as wainscoting, although a fully tiled bathroom was not uncommon.

White tile bathrooms were seen as especially sanitary, which was very good. But by the 1920s, it became popular to start having wall paper and pattern in the bathroom, taking it from a clinical exam room to a more feminine and family-friendly place.

By this time, the Victorian claw-foot tub was going out of style. Most homes no longer had cleaning staff to do the dirty work, and cleaning up under an open claw-foot may have hastened its demise more than any stylistic fad. First came the bathtub on a solid pedestal base, and then came the two-sided enclosed tub, resting on the floor. No more worries about cleaning under the tub.

Other lifestyle changes were worked out in bathroom styles and preferences. The shower, which was more of a novelty than a necessity, was gaining in popularity. As the automobile allowed people to move farther away, into the new suburbs surrounding our large cities, commutes became longer, and one’s morning ablutions became more rushed. A shower is quicker and easier than a bath, and by the 1930s, every middle-class home, and above, had a shower, either as separate fixture, or a wall mount in the bathtub.

In 1927, the Kohler Company introduced the bathroom set: matching sinks, toilets and tubs. It was not only a great marketing tool, it heralded the beginning of the acceptance of the bathroom as not only a sanitary necessity, but an important room to be decorated, with care and an important expenditure of funds.

All of the leading bathroom appliance manufacturers followed suit, and began making a multitude of products for the modern bathroom. Their Victorian forebears had multiple lines of products, and there were many kinds of lavatory sinks, several basic toilet designs, and some variations in bathtubs, but they were geared towards a higher end market.

The modern era would mean something for every income bracket, offering a large variety of products. If white wasn’t your thing, they would offer color.

Today we view some of the colors offered with horror. Hunter green, dark pink, burgundy, black, light pink, light blue, and tan toilets are now fodder for the dumpster or salvage yard, except to those who love retro.

But then, they were seen as cutting edge in bathroom chic, a matching set coordinating with similar colored 4-by-4-inch tile walls, usually with a contrasting color as trim. We’ve all seen those pink and black bathrooms somewhere in our lives. The dark colors were especially popular in the 20s and 30s, and the lighter colors later in the 50s and 60s, but that was not a hard and fast rule.

It seems hard to believe, but the rest of the world, including most of Europe, is way behind us in advances in bathrooms. London only became completely indoor plumbed 50 years ago, and old privies can still be found in the backyards of row houses there.

By the 1950s and 60s, the new suburbs were being developed, the Levittowns of America. The smaller houses may have had only one full bathroom, but as houses began to get bigger, so too did the number and size of bathrooms. New terminology had to be developed.

The ensuite bathroom and the master bathroom became de rigueur in many circles. As the housing boom of the post-World War II generation continued, it was no longer acceptable to have only one full bathroom. A powder room was needed for downstairs, and for guests, with a toilet and sink.

Now the master bedroom, that is, the parent’s room, needed its own bathroom, with another for the rest of the house. Ensuite bathrooms are those that are only accessible from a bedroom, perfect for the master bath. A proper master bath had everything: a tub, separate shower stall, toilet, and a double sink.

A shower room is a bathroom with only a shower. It is sometimes called a three-quarter bath in real estate parlance. Today, many apartments no longer have tubs, just shower stalls. A Jack and Jill bathroom is one that has two doors, usually accessible to two bedrooms.

Some larger bathrooms have a separate toilet cubicle, and many have double sinks. A wet room is a bathroom that becomes a shower stall. These used to only be in very small apartments, but are becoming popular again.

A floor drain allows the water to drain away, and most are designed to spare at least one side of the room in order to hang towels, accessories and toilet paper without them getting soaked.

The modern era has seen a remarkable plethora of bathroom goodies. Cast iron has been replaced by acrylic and fiberglass, making today’s tubs much lighter and, some would argue, much cheaper in quality. If you have the money, a bathtub can be a modern glass egg, a Japanese wooden bath, or an ancient Italian marble soaking tub.

Even Victorian claw-foot designs are back. Jacuzzis, whirlpool tubs and massaging baths make cleanliness an experience. Sinks have gone from the white vitreous china or enameled porcelain to glass, metal and stone vessels that sit on top of a table. Non-traditional materials abound, as anything that can hold water has become a sink or a tub.

Fixtures have changed as well, with all kinds of shapes and materials imaginable, from vintage Victorian to ultra-modern. Toilets are now space-aged devices, springing from walls, or perched like sculpted objects. Showers can be double and triple sized spaces, with hundreds of directional jets, or an overhead waterfall or shower.

Tile is no longer just tile, you can line your bathroom with all kinds of stone, metal or coated surfaces. The possibilities are only limited by budget.

Today, it seems that it is expected that every bedroom in a house is now supposed to have its own bathroom, plus a couple extra for downstairs. Real estate ads that list more bathrooms than bedrooms are not uncommon.

This is not feasible in most of our brownstone homes, however, because there just isn’t the room. Yet we try to squeeze another bathroom wherever possible: in a bedroom, a closet, or under the stairs.

The highest form of bathroom chic is to be able to devote an entire room to the bath, with a large tub in the middle of the room, often in front of a fireplace, for that ultimate, private bath experience. We’ve come full circle. Except now we don’t have time to enjoy it.

For many, Victorian bathroom fixtures are the only way to go in outfitting a period house. Period tubs, sinks, and even toilets, as well as accessories like towel bars, soap dishes, and the like are still available via salvage stores. Reproductions also abound.

Related Stories

- Walkabout: Let’s Talk About Bathrooms, Part 1

- From Open Hearths to Open Plan: 350 Telling Years of Kitchen History

- 7 Fabulous Victorian Bathrooms Keeping It Old School

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment