Growing Pains: Park Slope-Based Cartoonist Adrian Tomine Contemplates Life and Work

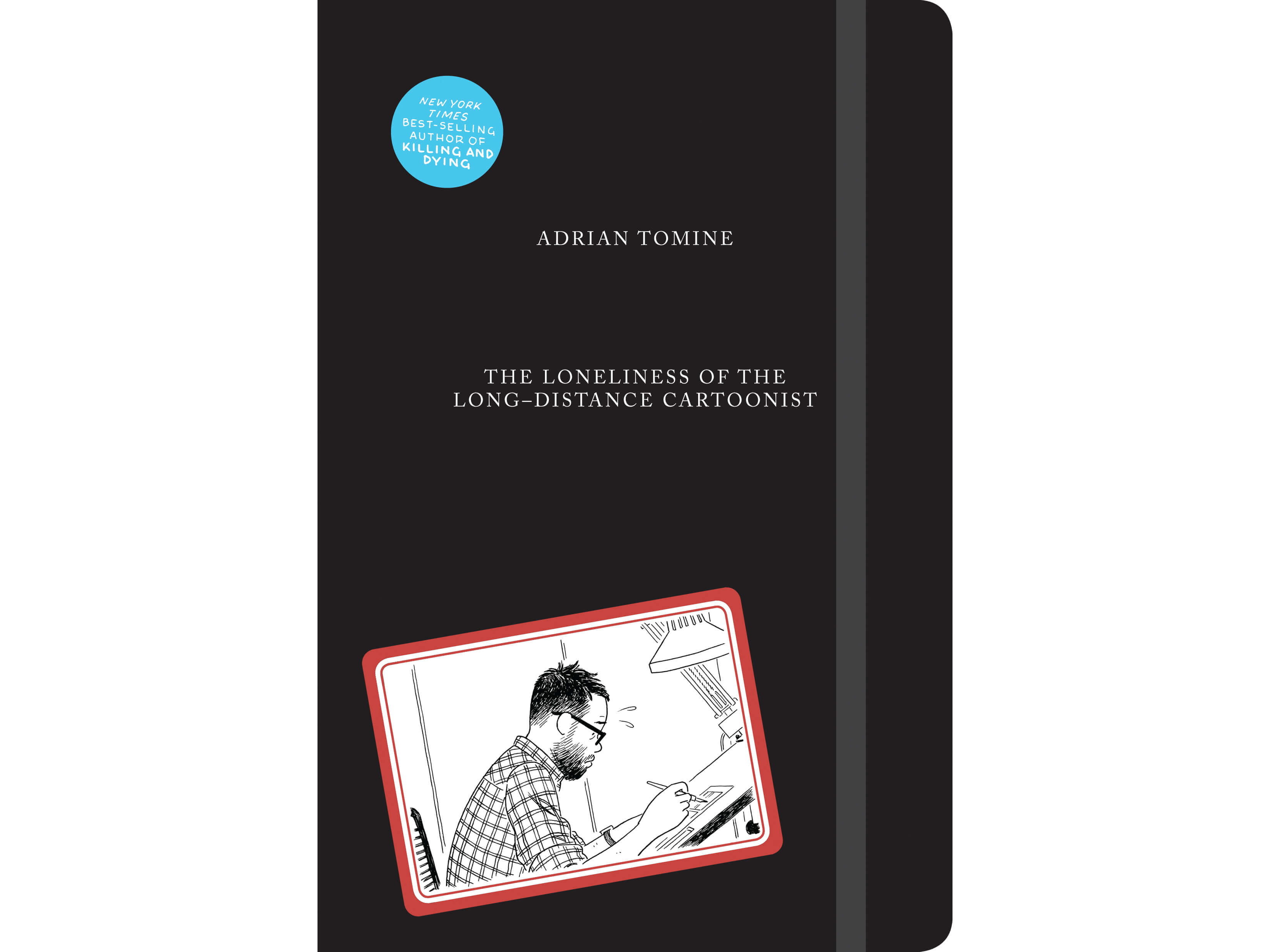

The well-known New Yorker cartoonist reveals the creative process behind his latest graphic novel and comedic memoir, “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist.”

Photo by Susan De Vries

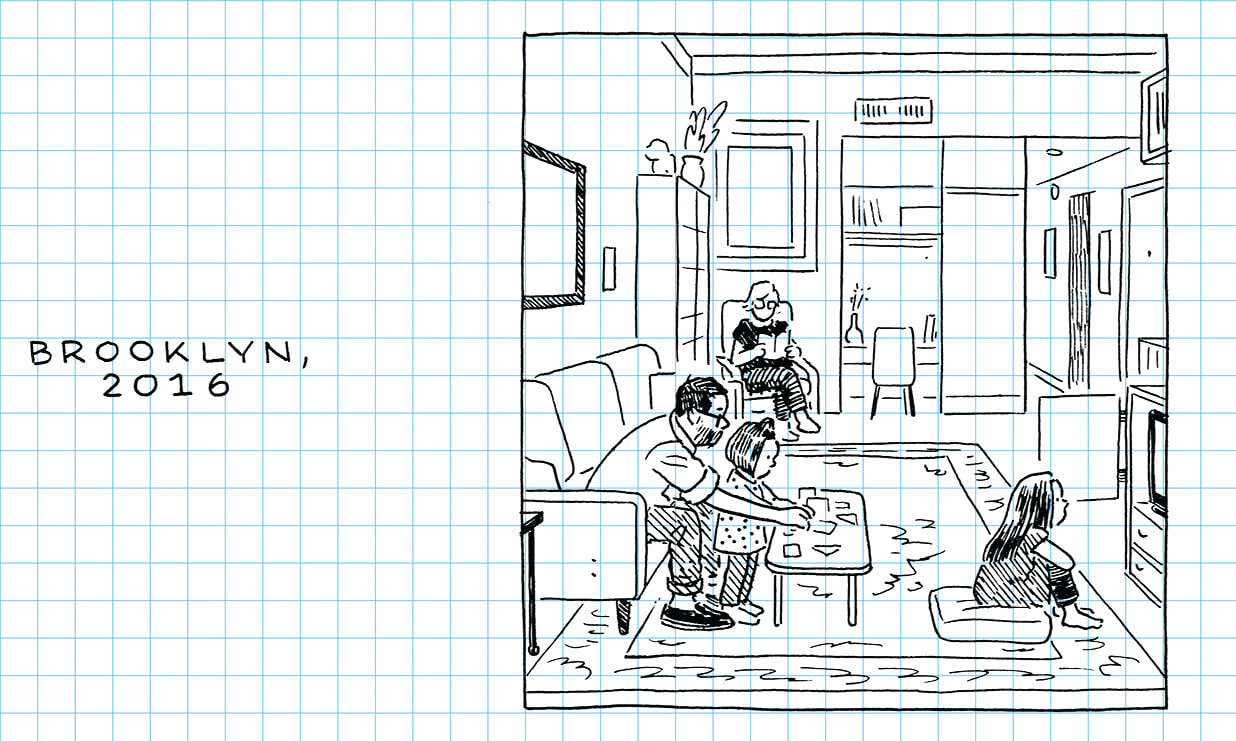

Adrian Tomine had a problem. The artist, known for his popular graphic novels and illustrations for The New Yorker, needed to figure out a new way of working for his next book. The last one, 2015’s “Killing and Dying,” while one of the most well received books of his career, had taken a long time to finish. It was a book that he started after moving to Park Slope in 2004. In the process of completion, he got married and had children. The freedom he had to focus on his work, along with the methodical, time-consuming methods of drawing he had developed over a number of years, had been interrupted by more pressing matters: familial responsibilities.

“It definitely was a grueling setup I found myself in and I was happy to move away from that as soon as that book was finished,” Tomine said. So when beginning “The Loneliness of a Long-Distance Cartoonist,” his latest graphic novel, he needed to find a way of working in harmony with his new life.

“There was a very conscious attempt to almost trick myself into working in the way that I had worked in the early days,” Tomine said. “Some of it was a complicated mental trick of blocking out thoughts of a readership, or critics, anything like that. And some of it was as simple as getting rid of any extensive or fancy or delicate tools. I found that just using cheap paper and pens, things that if they broke I could throw away and get another one easily, really freed me up. The new book is an intentional regression, in a way.”

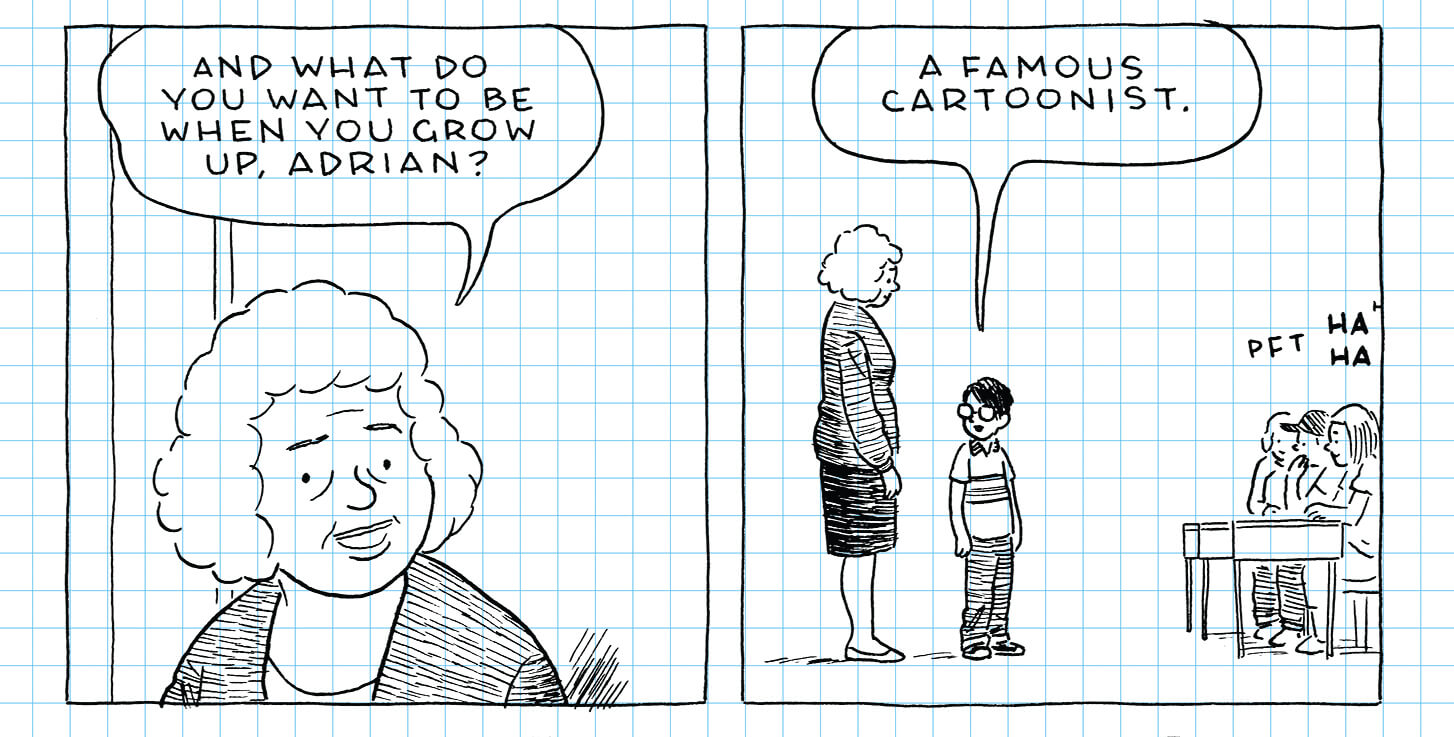

Despite the difference in approach, readers of Tomine’s previous work — including his comic Optic Nerve, which he started publishing in 1991 at the age of 17, and the graphic novels “Sleepwalk,” “Summer Blonde,” “Shortcomings,” “Scenes From an Impending Marriage,” and “Killing and Dying” — will quickly find a familiar vision. Few working in any medium are able to combine the same level of self-effacement and tender emotion. Loneliness takes this to greater extremes, his pen trained to a series of moments throughout his life that, together, tell the story of an artist coming to terms with his profession and the strange twists of modern life.

Has the way you make your work changed over time?

It’s been a crooked path to get to the point I’m at now. The earliest comics of mine that are in print were done when I was a teenager, and they were done with a completely unselfconscious approach. I wasn’t thinking of an audience in any way. Over the years, when I started working in a more professional capacity and having my work distributed more widely, I certainly got more self conscious, more perfectionistic, and very focused on how the work would be received. So I think that really started to slow me down. In “Shortcomings,” I was doing about a page a week, going out and taking reference photos for the backgrounds, doing layers of pencils on tracing paper and then tracing it back before inking it. I don’t think all that work even shows up. Nobody ever says, “Oh, that’s the book you spent a lot of time on.”

Is each book created as a response to what came before?

It’s always a bit reactionary to what I did just before, in terms of content and style. But also “Killing and Dying,” and definitely this new book, are influenced by the practical matters of my life—having kids, how much time I’m going to have to work, what level of interruption I’m going to have to expect. Most of “Killing and Dying” was made just as my kids were being born, and it was tough. It was a hard book for me to get done, but at least it was short stories. So I felt like, “I just need to get through these eight pages and then this chunk will be done and I can move on to something else.” With this new one, I knew I wanted to do one complete book, but I wanted to have a style where I could get a page done in a day and work with distractions. Basically, I was freer to be a parent.

Is it difficult to dredge up memories, some of which, as presented in the book, were quite embarrassing or humiliating?

There’s a certain amount of research that was required. My memory is not perfect when it comes to dates and details. In some cases, it involved doing some math and looking up old journal entries. I’ll be the first to admit that the book gets more precise and accurate as it gets closer to the present day. The earliest stuff in the book is vague, very filtered memories. I tried to be forgiving of myself if it wasn’t journalistically precise.

Was the move from the West Coast to the East Coast reflected in the work?

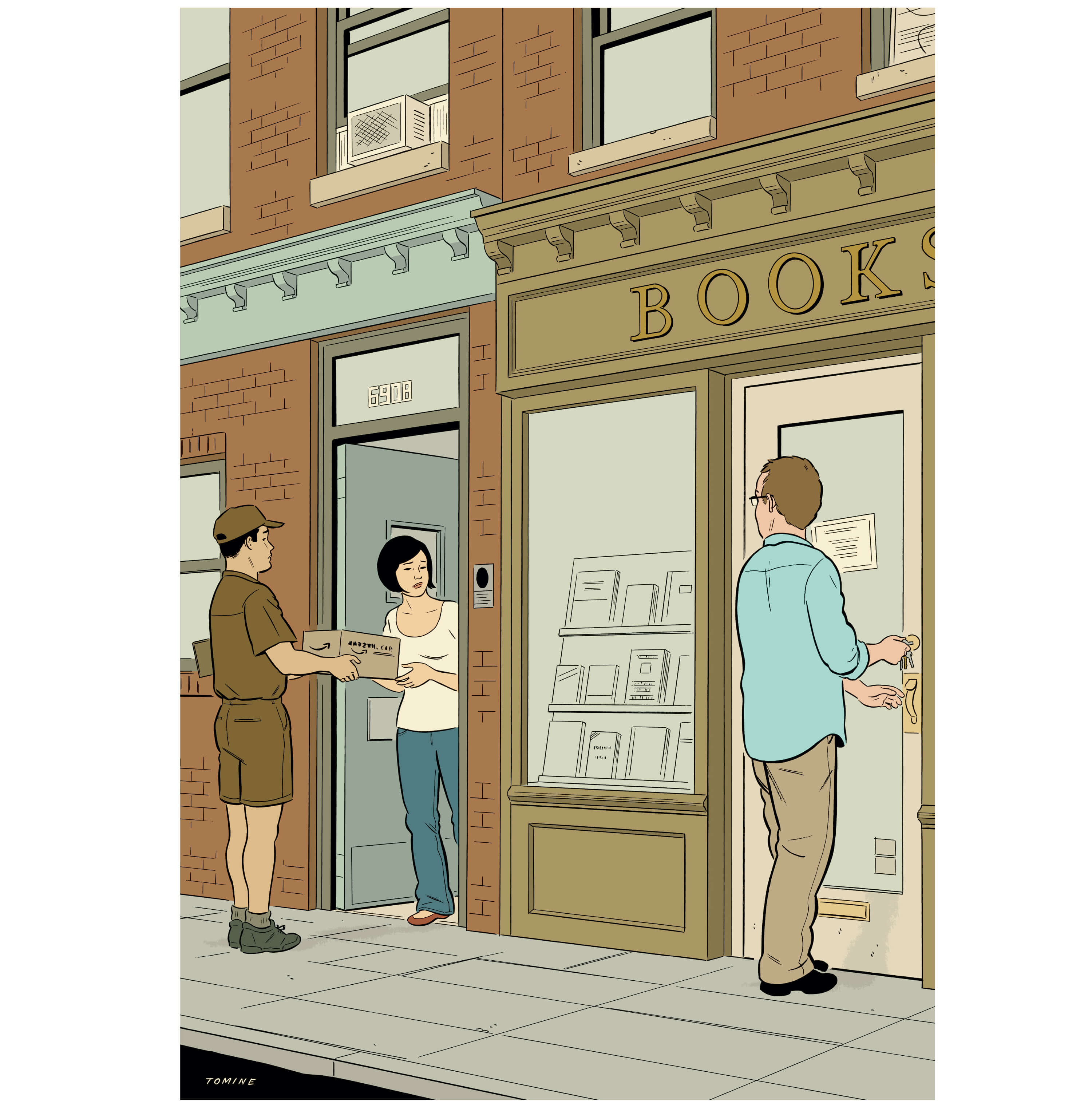

I think there is a lot of that emotion and atmosphere in “Shortcomings.” That was a book I started in California and finished in New York, which coincidentally is reflected in the subject matter. I also started doing a lot more work for The New Yorker when I got here. I was doing a lot of location-specific assignments, where they would send me to a restaurant to draw the inside or send me to The High Line. If you look at the illustration work, I think it gets more specific to New York.

Did working at The New Yorker and getting those types of assignments allow you to feel more comfortable living here?

It definitely helped. I basically moved to get married and start a new life here. So working for The New Yorker helped a lot with the introduction of me to my in-laws. To them, The New Yorker meant something. I wasn’t just a cartoonist; I worked for The New Yorker. And I get to know things, people, and locations by drawing them. This was before I had kids, so I did a lot more walking around and drawing in sketchbooks. Some of that was on assignment, some of that was just something that I did because when you don’t have kids you have so much free time. That was, I think, serving two purposes. It was easing me into these new surroundings, which were a little overwhelming. I don’t think I achieved it but I think it was a vague attempt at getting a mastery or comfort over the unease that I was feeling. It was also a very blatant attempt to look like a real artist to my wife—the guy who is walking around with a sketchbook and drawing. That’s not something I normally do very much.

Some of the covers you have done for the New Yorker have become iconic pictures of a city that you were just wrapping your head around when you drew them. People might not even be aware that, for much of your early career, you were thought of as a California artist.

I still feel like a California artist. I’ve lived here a long time now but I still feel like I’m a Californian that’s been transplanted here. I feel like I have a little bit more authority when it comes to setting stories in California and writing about those people and locations. “Killing and Dying” didn’t require a lot of research. If I set that here, I would be like, “I don’t want to screw up because the real New Yorkers are going to know.” They are going to rake me over the coals if I get one detail wrong. And I don’t know if that will ever change. I don’t know if I’ll ever feel like some authority and to have the confidence to write about and draw New York.

Which is odd, because there are people who think of you now as specifically a New York artist.

I’m always blown away when I see bootleg versions of my New Yorker covers in Times Square, or something like that. There’s a long tradition of people coming to New York from somewhere else and pretending to be locals.

Was there trepidation in writing so directly about your life?

I think to some readers this will look like the easiest book for me to put out. Or that I just took pages out of an existing sketchbook and published it. I’ve either done things that feature me as a character but are light and fluffy, with almost like sitcom-like gags. Or I’ve done things that are personal but cloaked and veiled in a million little reflecting mirrors that I can hide behind. So, for me, the biggest challenge of this book was getting ideas that I had in my head and getting them down on paper. Because all the material was very clear to me but then almost every story I would have some moment where I’d be like, “I don’t know if I want to tell this story. Is it right to put this out there?”

For what reasons?

The most selfish one being that I’m a private person. In general, I keep to myself and don’t expose myself in the way that a lot of artists do now. That was hard for me. Also, just taking into account other people. It would be easy if it were just 100 pages of me sitting in a room talking to myself. But I have to interact with other real humans, so there was a lot of hand wringing with my own conscience. There are certain things that I omitted or changed, and you’ll notice that at some moments in the book names are scratched out. That was an edit that was happening up to the very last minute.

For the people in your life who are portrayed in the book, is that a conversation that needs to happen with them? Or are you using your own judgment on what is fair to them or not?

Well, the general rule that I set for myself is that I need to be as open and as brutally honest as possible about myself. As a reader, I would be really annoyed with a book like this that felt like it was protective of the author’s ego. Beyond that, I feel like, in general, I was pretty innocuous in my depiction of most other people. I don’t think there’s anybody who would get embarrassed by what I depict. If there were any doubt on my part I would err on the side of changing people’s appearance or crossing out their names.

How did the story change as you were creating the book?

To me, there are a couple of stories that are told in the background of this book. In the foreground it’s a comedy about the mishaps of being a cartoonist. But as I was planning it out, I realized it would be evident to some readers that it’s about me leaving home, leaving California, moving here and having kids, having a domestic life.

Is being an artist still a lonely endeavor for you?

There are often days where I feel like I sort of painted myself into a corner, I’m trapped in a life I can’t stand to live another day, and then something will come around to change that and I’ll want nothing more than to return to the usual routine. I didn’t want to have a story that wrapped up with some sort of salvation or something like that. When I posed the topic of this book to myself, and tried to explore it mentally, I just kept coming up with very mixed emotions. And I thought, “Well, actually, that’s probably the most honest way to write about it.”

Those mixed emotions are something I imagine most creative people will find relatable.

I don’t know if this is true of younger cartoonists, because the field has changed so much since when I started, but I know for me and my peers and maybe the artists who were inspirational to us, loneliness is just a huge through line through cartooning and the lives of cartoonists, whether you’re looking at someone like Charles Schultz, probably the most successful, most famous, richest cartoonist of all time. To the end, he seemed like a lonely guy. I think that’s sort of a chicken and the egg thing: It requires that sort of personality to do the work of a cartoonist but doing that work only reinforces that emotion.

And doing that work also requires forced sociability—book tours, conversations like the one we’re having right now.

If I were born 20 years earlier I probably wouldn’t have had a career as a cartoonist. I probably would have had a job and drawn comics in pure isolation. No book tours, no interviews. No photos taken or anything like that. Now, the upside is that I get to make a living doing this; I get to live in an expensive city. There are aspects of it that you can’t avoid. You have to promote a book when it comes out, and if your books sell to the right amount you’re inevitably going to have to field phone calls from people about the rights to adapting it. I guess you could cut that off if you wanted too, but if you’re a father who’s struggling to support his kids in Brooklyn, you have to take those calls and take those meetings. There’s a lot of face-to-face stuff involved in being a cartoonist that never existed before.

Now that this book is coming out, do you have any idea what the next thing will be?

Something where I don’t have to draw myself over and over again. I got that out of my system for the time being.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2020 issue of Brownstoner magazine. It was completed before the pandemic.

Related Stories

- How to Leave Brooklyn: A Farewell From Two Photographers

- Actor, Activist and Designer Gbenga Akinnagbe Finds a Home in Bed Stuy on His Way to Broadway

- Jonathan Lethem Comes Home

Sign up for amNY’s COVID-19 newsletter to stay up to date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment