Locals Oppose Freehold's Plans to Open Nightclub in Former Artist Lofts in South Williamsburg

A plan by popular Brooklyn cafe and nightclub operator Freehold Brooklyn to open a venue in a former factory turned artist lofts in a busy but troubled area in south Williamsburg is in doubt after locals representing thousands of nearby residents spoke against it at a recent community board meeting.

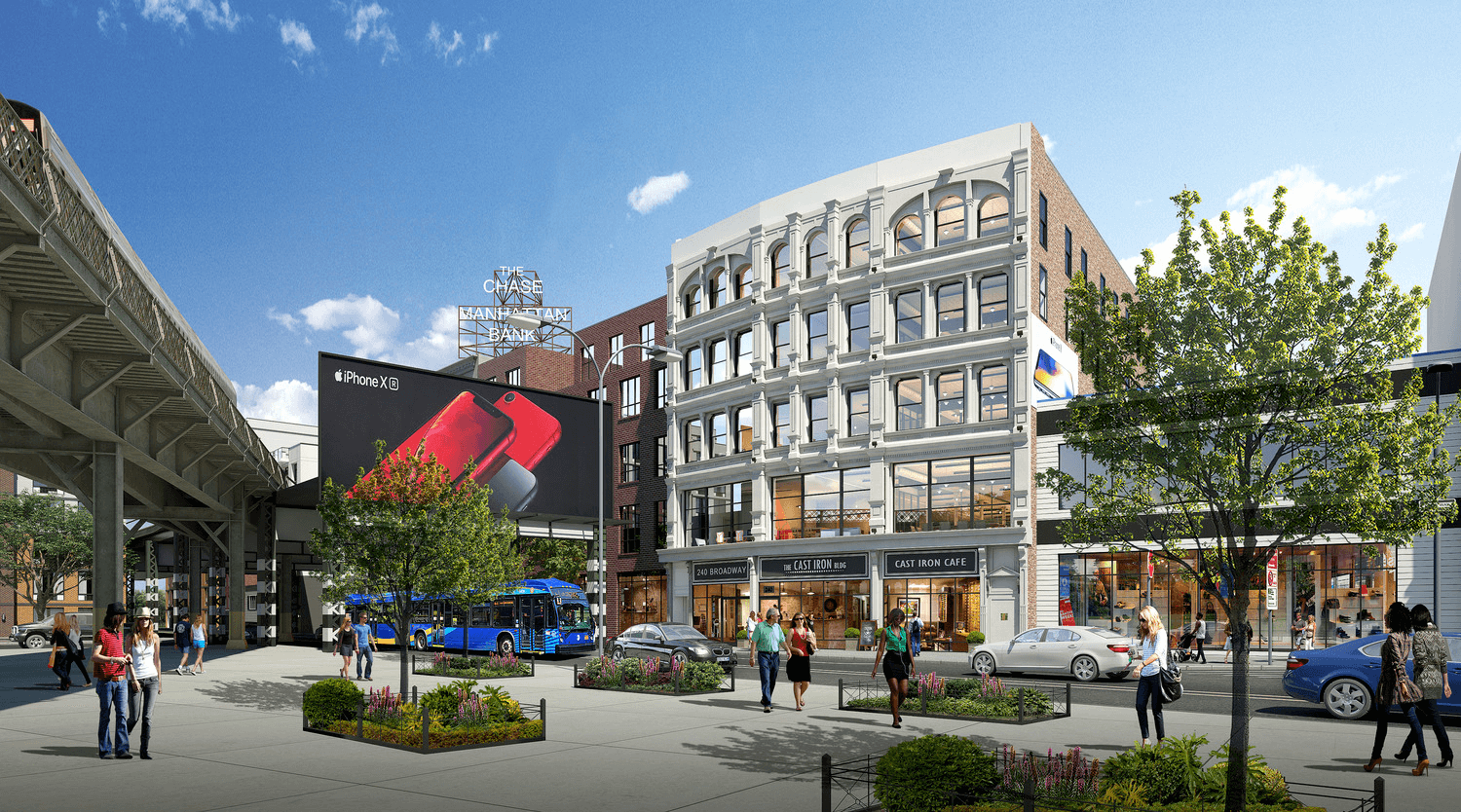

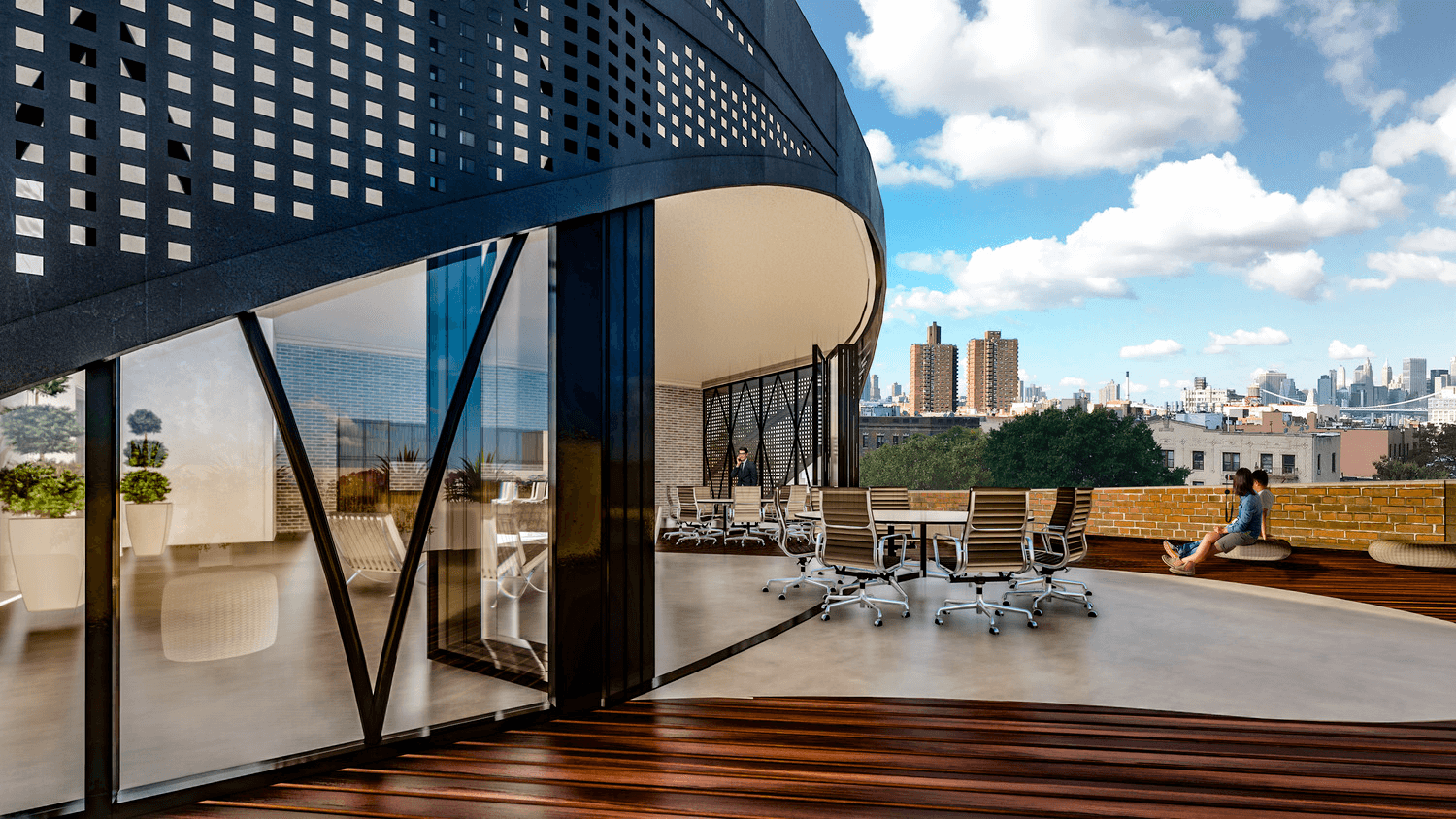

The building at 240 Broadway is currently being converted to commercial space. Photo by Anna Bradley-Smith

A plan by popular Brooklyn co-working and nightclub operator Freehold Brooklyn to open a venue in a former factory turned artist lofts in a busy but troubled area in south Williamsburg is in doubt after locals representing thousands of nearby residents spoke against it at a recent community board meeting.

The 1892 cast-iron and brick building at 240 Broadway – designed by prolific Brooklyn architect Theobald Engelhardt – was most recently home to residential tenants in 24 loft units, many of whom had been living there for decades, and who were kicked out in 2019 when new landlord ZB Capital Group purchased the 36,254 square foot building for $20.1 million.

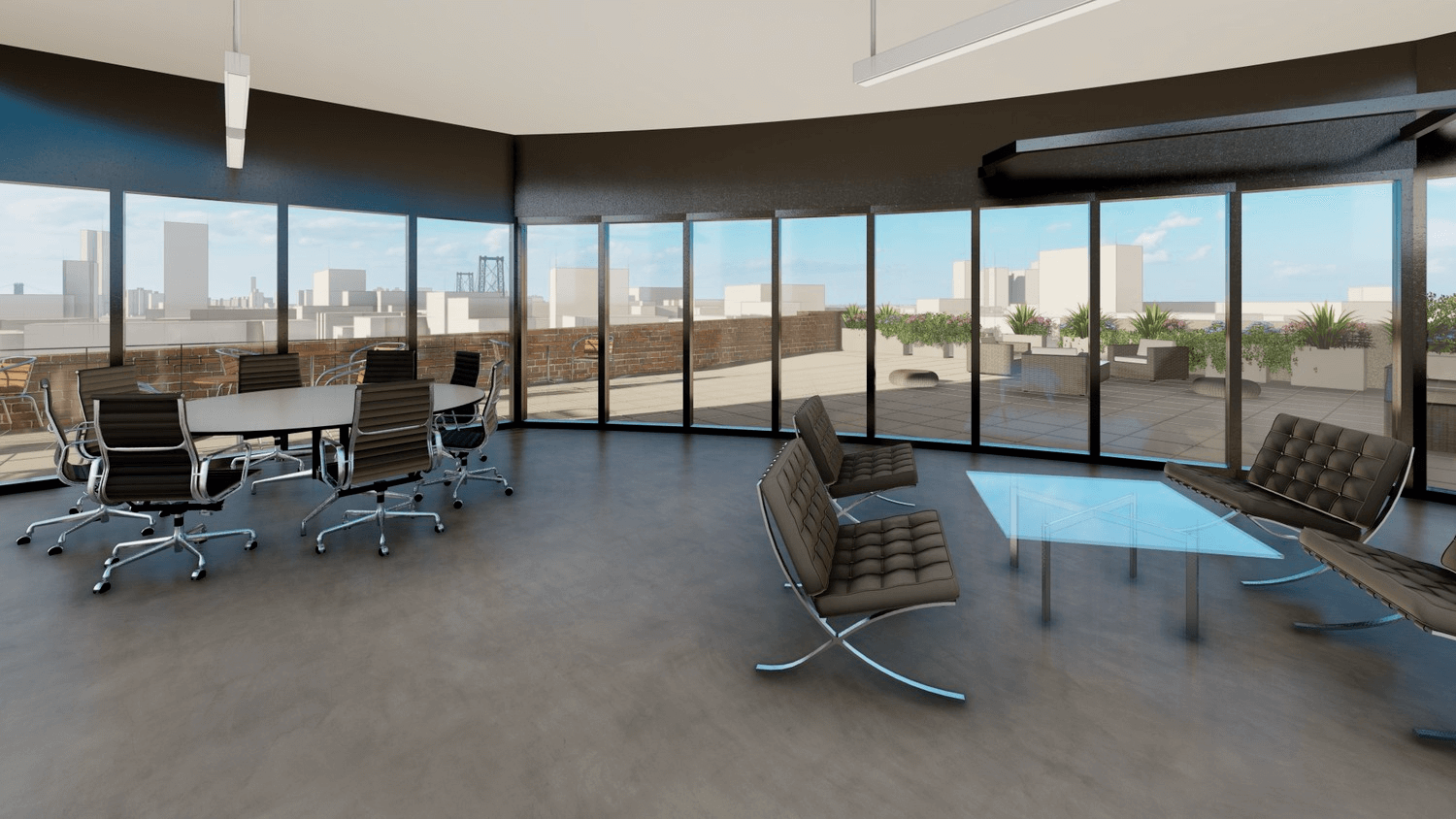

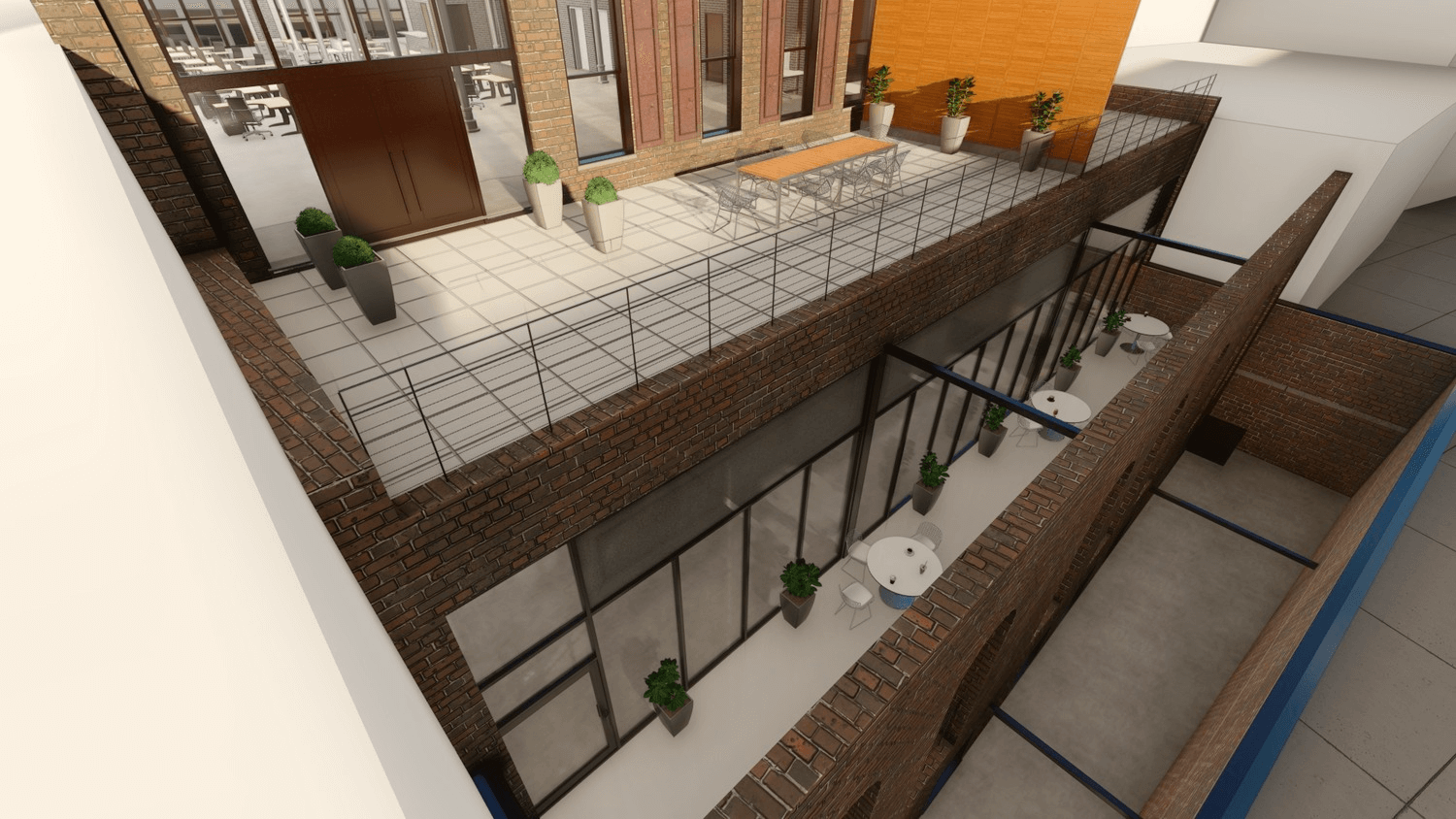

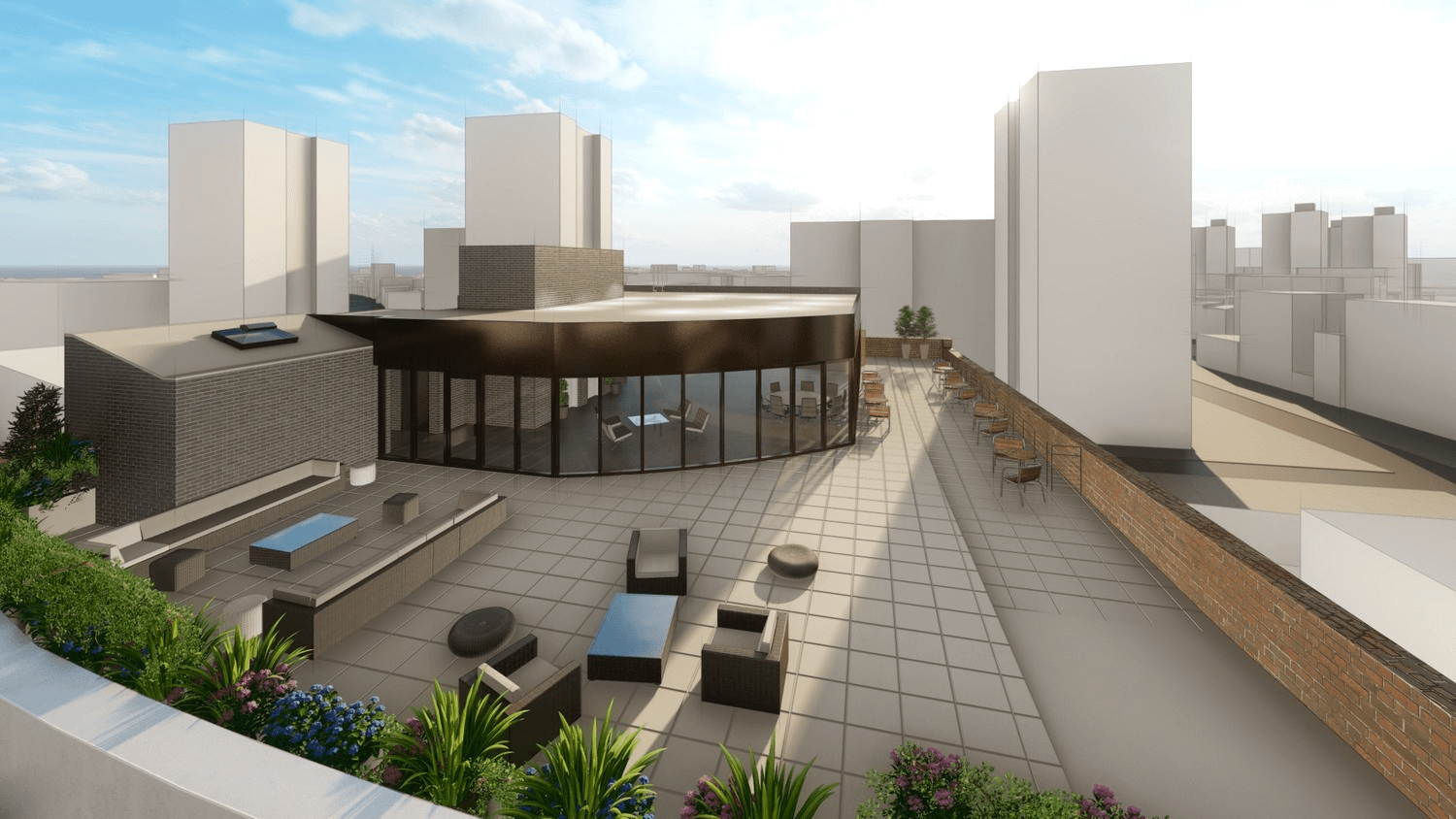

The new owner has hired architect firm Mancini Duffy to restore the facade and convert the building to a commercial space that will include a restaurant and bar on the first two floors, as well as a rooftop bar, and offices on the upper three levels.

The street-facing facade is currently covered in scaffolding and surrounded by a construction fence, and workers could be glimpsed inside the building when Brownstoner stopped by on Thursday. In 2020 and 2021, alt-1 permits were issued to change the usage of the building from residential to office on floors two through five and to renovate the existing store and storage space on the first floor and in the cellar.

In 2021, after the building changed hands, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, which allows the developers to apply for tax credits to undertake its restoration if they follow certain preservation guidelines.

According to the architect’s website, the firm is working with a historical research consultant to restore the cast-iron facade.

The building will get a “full modernization, including the addition of mechanical systems and at least two new elevators,” the site adds. The interior layout will be reconfigured into white-box retail and office space, and a penthouse and outdoor amenity spaces will be added. Renderings show the street-facing facade will be white, while the west-facing facade will remain red brick.

While the current plan is for Freehold Brooklyn to take the tenancy in the hospitality space, opposition from local residents could derail that.

Freehold Hospitality cofounder and CEO Brice Jones and his lawyer Frank Palillo presented plans for a new outpost of the popular cafe, restaurant, co-working and event space, and nightlife venue — which has locations in Williamsburg such as at 45 South 3rd, Manhattan, and Miami — at a recent Community Board 1 meeting.

Locals concerned about noise, crowds

Overwhelmingly, board members said they have concerns about the hours of operation (until 4 a.m. seven days a week, according to the liquor license application), noise from the planned rooftop bar, the crowds that would gather in the already congested area around the Marcy JMZ subway station, and intoxicated people heightening safety issues in what they say is a heavily residential neighborhood.

“Just for Williams Plaza, our development here where I live, I am representing 1,800 residents in this development alone who are opposing this particular applicant,” said board member Joel Gross. Williams Plaza is the 577-unit NYCHA development behind 240 Broadway.

Gross, surrounded by other Williams Plaza residents, said they object to the hours of operation, the 450-person capacity without a parking garage, and live music. He also raised concerns about congestion along Broadway and how it could affect emergency service vehicles, as well as safety for local residents who work late night or early morning shifts and would have to navigate large crowds to get to public transportation.

“The community feels this facility will be an issue of quality of life, a safety, a security issue,” Gross said.

Bella Sabel, who has lived in the community for more than 60 years, spoke of similar concerns, saying a venue that operates into the early hours of the morning would “hurt a lot of families” in what she said is a residential neighborhood. “Logically, it doesn’t make sense.”

She said the area already has a number of issues to deal with, and it doesn’t need to be burdened with more.

The building at 240 Broadway was originally built in 1892 as a spec factory. Early tenants included home furnishing and apparel makers. During the mid-20th century, a bowling alley occupied the second floor. As Williamsburg has developed over the decades, and Robert Moses put the BQE highway and a bus depot through the middle of the area’s central square, the building has found its surroundings very much altered. The city’s historic tax photo show the building itself relatively unchanged, except for the loss of its impressive cornice.

Situated under the elevated JMZ subway tracks, the building at 240 Broadway is now in the middle of an extremely busy area where cars enter and exit the Williamsburg Bridge and navigate the BQE, a large bus depot sits across the road, and crowds of pedestrians navigate narrow sidewalks and dodge vehicles on their way to and from the subway. There are also issues with crime in the area, especially in the later hours.

Board member Stephen Chesler said the plan to bring crowds to the “compact area” seemed “in direct conflict with the neighborhood, in the evenings especially.”

Thanks to a 2005 rezoning, the north side of Williamsburg has seen new glassy high rises, multimillion dollar corporations, and a swath of new residents move in and out over recent decades, as well as a robust nightlife scene centered in the neighborhood’s industrial zone near the Wythe Hotel and McCarren Park. While the south has also experienced gentrification and development, it has been somewhat more insulated from the changes. Implied in many of the board members’ comments was that they didn’t want to see what had happened on the north side move to the south.

Iris Cabrera, who worked for neighborhood organization Los Sures where Jones volunteers, said that while she appreciates the work he does in and for the community, that doesn’t mean she could support a move that might hurt the south side community.

“You have business in the north side, which does not have a lot of families living there,” she said. “I have a family. Yes, I live next to the J and next to the Z, so I don’t want more noise on top of that that won’t allow me and my family to go to sleep when I have to wake up early in the morning to go to work.”

She said if Jones is able to keep the sound inside the venue so it doesn’t affect nearby residents, she didn’t see an issue, but said “having a rooftop that closes at 4 in the morning, I’m sorry my love but that’s a no no no.”

Freehold CEO hears feedback

At the meeting, Jones answered concerns raised by board members and said ultimately he wants to respect the community’s wishes and be embraced in any new location he opens in.

He said he heard loud and clear the concerns about noise coming from the rooftop and the issues with hours of operation and he is happy to make changes to the company’s plans to better satisfy local residents. He added that according to the company’s study and zoning documents, the building and surrounding city infrastructure could handle 450 people, and said his footprint would be no bigger than steakhouse Peter Luger, and noise no louder than live-music bar and brunch spot Baby’s All Right, both close by.

He stressed his investment in the neighborhood, and that he employs more than 200 people there. He said that while he is running a business that needs to make money to pay its rent and its staff, Freehold is also creating a community workspace where any member of the public can come and relax early in the morning and stay late at night free of charge.

The point of coming to the community board, he said, is to develop an operating plan based on what the community wants and what would work for a sustainable business.

“I’m applying for everything that makes sure my business can do well so I can serve my community, that way I can make money and employ the people I’m going to employ.” He said just because he was applying for a 4 a.m. license it didn’t mean he’d be open until 4 a.m. each day. He noted Mondays through Thursday would have earlier close times than weekends.

In a comment emailed to Brownstoner following the meeting, Jones said: “After hearing the concerns of the community at the community board meeting as well as following up with Senator Salazar’s office, we are meeting internally with building ownership to discuss the feasibility of the project moving forward.

“It is, and always has been, our hope to offer the community a hospitality concept that will not only benefit the community, but be received with open arms.”

If Freehold doesn’t go ahead with its plans, whether another venue will try for a liquor license in the space is an open question. Brownstoner reached out to the building owners to hear what their plans are, but did not hear back.

The building owners’ decision to convert 240 Broadway back to commercial space rather than keep it as residential units, given the premium on residential apartments, is unusual. It stands out especially in Williamsburg where new apartment buildings are constantly under construction.

End of an era in Williamsburg

For former tenant Arthur Arbit, who lived in a loft unit in 240 Broadway for nearly 20 years, the eviction and subsequent changes in the building “was exactly what was supposed to happen, it was the end of an era, this is what was happening in the neighborhood and we just happened to be in the line of fire.”

Arbit, who immigrated to Brooklyn from the Ukraine in 1979, found the apartment through a friend who happened to be the building’s superintendent. As a tailor, the open plan space worked perfectly for him with 16 foot ceilings and floor to ceiling windows looking over the subway tracks. “At night, when the train passed right by your windows, you felt like you were in a film noir. It was an epic place.”

He said the tenants had created a tight knit community whereby everyone knew everyone, and they’d help each other out with fixing issues in the old building after its “hurried conversion.” While the former landlords had an office in the lighting store that occupied the ground floor and were accessible, he said “they weren’t in a rush to fix things,” and some things might not have been strictly to code.

“There were industrial heaters installed in residential spaces, you know, like your kitchen vents went nowhere. But remember, this was still a generation of people who could take care of themselves, people who could fix their plumbing and if there was a leak you knew exactly who to call,” he said.

“So in that sense, you know, it was kind of like the last of the Mohicans.”

Coming to Williamsburg in the ’90s and opening an art gallery in Greenpoint, Arbit said he considered himself part of the second wave of gentrifiers, and that he was hyper aware of the impact of his work. It included opening Mighty Robot and hosting a number of live music shows in the neighborhood, as well as founding and running Williamsburg Fashion Week.

“We were aware of what was happening, we treaded as lightly as we could, but we knew, we watched it happen. We watched the profile of the residents change,” he said.

“When the rents were reasonable, the misfits from all over the country who did not fit into their little towns, there was New York and LA. So they all came here and they could afford to be themselves. Eventually the rents became so high that those people could not afford them and you could see it in the streets, the clothing became generic, it was no longer inspired.”

When the eventual eviction letter was sent to him and the other residents, he said they were ready to put up a fight but knew they were dealing with a new owner who had “bottomless pockets” and wanted “a Williamsburg feather in their cap.”

In 2019, the residents called on the Department of Buildings to revoke 240 Broadway’s 2003 residential certificate of occupancy, saying the renovation was not up to par and the building was rife with dangerous conditions. If the certificate of occupancy was revoked, the tenants would have been able to apply for Loft Law protections, something that can only be granted to those living in industrial buildings without a residential certificate of occupancy.

To add to the tenants’ claims, the conversion had been handled by architect Henry Rudasky, who was sanctioned by DOB along with his business partner for incorrect paperwork and was the architect behind a Bay Ridge building that collapsed during construction, killing one construction worker.

DOB did undertake an audit of 240 Broadway and found “several deficiencies that were inconsistent with the approved plans and subsequent inspection” according to a story in The City, but the agency said “there is insufficient proof to demonstrate that the deficiencies existed at the time of the issuance of the certificate of occupancy.”

In a statement to Brownstoner, a DOB spokesperson said: “Our comprehensive audit determined that there was not sufficient evidence to prove the 2003 certificate of occupancy was issued improperly, and that as a result the department would not be applying for its revocation.”

Arbit said after reaching a settlement with the new building owners, the details of which have not been disclosed, the tenants all moved out. He has remained in Williamsburg, despite his disappointment with how the area has changed, saying pragmatically it is the best base for his upscale tailoring business.

While reflecting on the changing neighborhood and how he feels about his former home becoming a bar and restaurant, as well as offices, Arbit said he is considering seeing if he could move back in as an office tenant.

“I’m going to tell them that I’m an old resident. If we could actually have the old space that we had, because we had the best space in that building,” he said.

“We will consider it because we have to roll with the punches.”

Related Stories

- Changes to the Loft Law Give Tenants the Right to Sue Landlords in Housing Court

- Fundraiser at 135 Plymouth to Save Loft Apartments

- As Williamsburg Tenants Fight Rooftop Battery Installation, City Moves to Make Them As of Right

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment