Actor, Activist and Designer Gbenga Akinnagbe Finds a Home in Bed Stuy on His Way to Broadway

The actor discusses his role at the center of Aaron Sorkin’s stage adaptation of Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

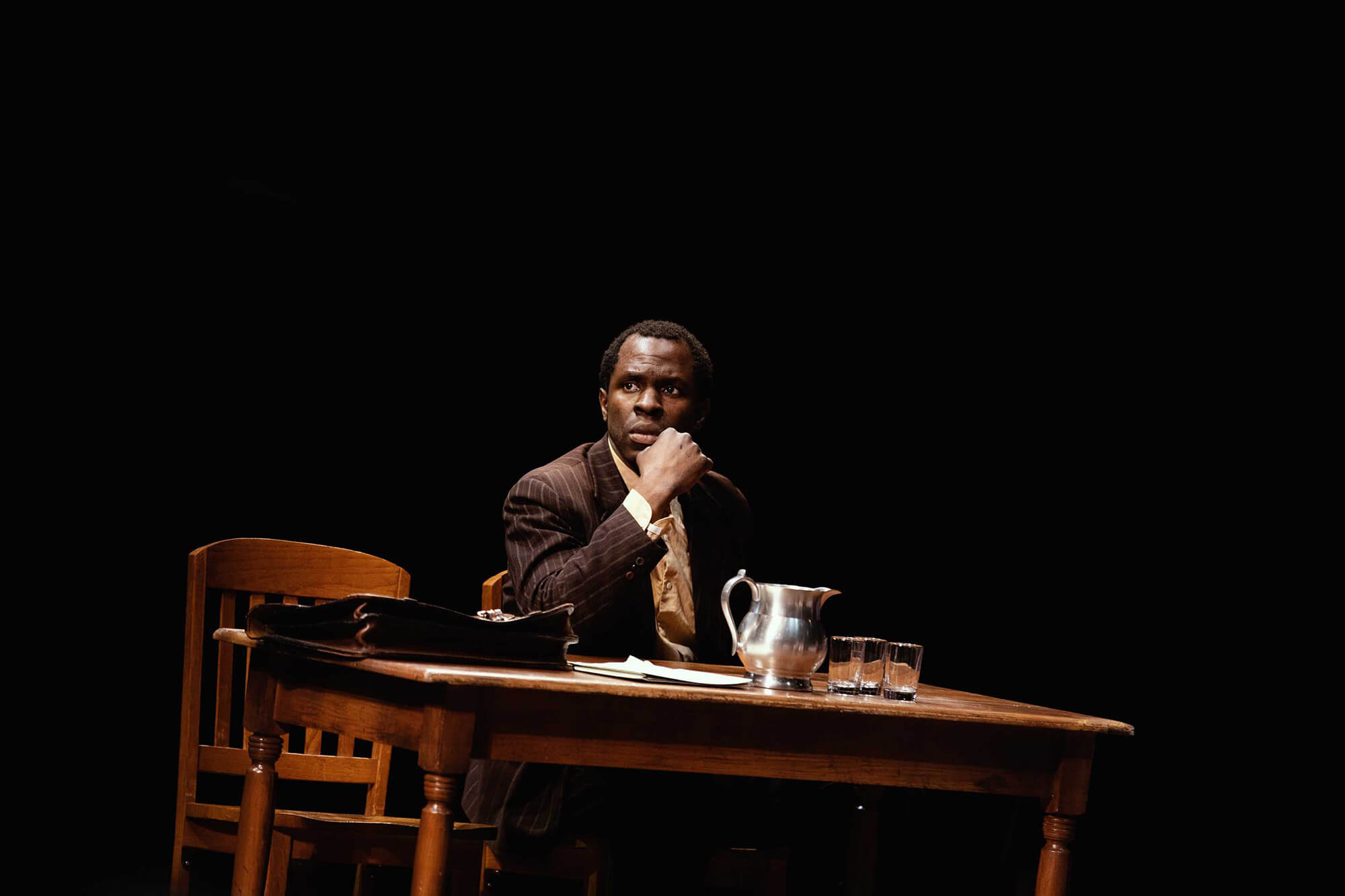

Photo by Steven Laxton

The way Gbenga Akinnagbe tells it, the plan was never to live in Brooklyn. It wasn’t a goal, anyway, more of a path with no destination, one thing leading to another, he says, sitting on the edge of his seat at a small Bed Stuy coffee shop. It was unexpected, but it’s a place where he has settled down. “It’s hard to live anywhere else,” he says of the neighborhood. He likes the history and the rhythm of the streets. “But I love to travel. I love seeing different parts of the country,” he adds. London is a place he particularly enjoys, and there are parts of the nomadic lifestyle of his work as an actor, which requires him to occasionally be holed up in the middle of nowhere for long periods of time, that he finds exciting. But at least for now he’s sure of one thing: “Brooklyn’s home.”

How he got here is a story that seems to still surprise him. Born to Ghanaian parents in Washington, D.C., and raised nearby in a suburb of Maryland, he first appeared in front of a camera as an extra on the Baltimore-set HBO television show “The Wire” during its first season. It would prove to be the beginning of a long, lasting relationship: he would return to the show during the third season in a more prominent role, as Chris Partlow, the quiet, brooding second-in-command to the show’s drug-operation leader Marlo Stanfield (played by fellow Brooklynite Jamie Hector). “That’s my family,” Akinnagbe says of the creative team behind the show. He is currently one of the stars of “The Deuce,” a television show that takes place in the seedy underworld of 42nd Street, and which ended its second season at the end of 2018. It was co-created by David Simon and the crime novelist George Pelecanos, who were two of the main creative forces on “The Wire,” and Akinnagbe recently codirected part of an anthology film based on short stories written by Pelecanos, whom he calls a mentor.

“There’s a connection,” he says about working with the creative team behind both shows. “Everything’s not always smooth — we bump heads, there’s hurt feelings and so on. But I just love working with them. I’ve been very fortunate: I mean, I went from being an extra on that show to, you know, someone that has learned and grown creatively. They see and appreciate that and help nurture that.”

Part of that growth has been to branch out into other creative endeavors outside acting. In 2016 he started Enitan Vintage, a design company that pairs vibrant fabrics culled from Akinnagbe’s travels around the world with vintage furniture, and started Liberated People, a line of t-shirts and hoodies adorned with bold, conversation-starting activist slogans. In between, he managed to write articles for both the Travel and Health sections of the New York Times.

These days, he’s spending most of his time on Broadway in what might be his biggest role yet. Akinnagbe plays the character of Tom Robinson, a man wrongly put on trial, at the center of Aaron Sorkin’s stage adaptation of Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” which has been playing to sold out audiences at the historic Shubert Theatre since November (its run will extend until the end of 2019). Opposite Jeff Daniels in the role of Atticus Finch, Akinnagbe shines in some of the play’s most emotional scenes, including those where he is forced to silently face a racially motivated prosecution and receive the brunt of their harassment. While he may not have the most lines or the longest monologues, it’s his face that sticks with you long after the curtain has dropped.

What is the difference in the process between working in theater, film, and television?

For me it’s similar, but much more in depth when it comes to the theater. Well, at least in this particular instance, because we workshopped it for a year. We spent so many hours sitting around a table talking about the script, talking about the world, talking about class and race, hearing other people’s thoughts. Then acting it out again and then reading it again. So all of that layers in a certain way that you don’t get in, say, television, which is basically like a digital camera and the theater is more like analog, where you’ve got the process of all these moving parts in order to get to this performance. That may or may not work, so you do all the work, hopefully, to increase the chances that it works on stage. In film you know you can do another take and another take and another take. You have all these elements there conspiring to make you look good for the show. And not just physically good but hopefully come off well as far as the character. You have the luxury of more time to do that with theater and months of rehearsal.

Have you noticed any changes in your performance in “To Kill a Mockingbird” over time?

I have definitely gotten worse [laughs]. Whenever I talk about the show and doing it over and over and over, I reference yoga because it’s a practice. Each time you have to reinvest and find things to help you reinvest. So whether it’s the way Jeff [Daniels] says something different this time or whether someone moves different, you need something that helps you to center yourself right back into the story. Sometimes you may have a mark for yourself and you may hit that mark, sometimes you may not hit that mark. It’s like yoga: Am I going to get this pose or am I not going to get this pose? It’s not even actually about the pose—it’s going to be what it’s going to be, and constantly kind of telling yourself that.

What about the audience? When I saw the show, at least three cell phones went off.

Oh my god, I know!

That’s distracting for me watching the play. Does that affect you?

Yesterday, a cell phone went off when Celia [Keenan-Bolger] is giving her last speech at the end of the show. It’s a really beautiful, important speech. We’re all on stage, dead silent except for her speaking. Everyone’s paying attention and then a cell phone goes off and she does this magnificent thing of just like, stopping and just waiting for the cell phone to stop. And then she started with the speech again. She didn’t skip a beat but is also proving a point, you know what I mean? So sometimes you don’t wait, you know, depending on where you are in the play and it looks like you can overcome that with the momentum of the play. Then sometimes you just stop and let that person know, without saying anything, that we’re all waiting.

It’s got to be tough to enter this world every day. Especially for your character: He’s taking the brunt of all the abuse, from lots of people.

It’s a struggle. I try not to think about it before I get to the theater. Maybe I carry some of it with me. But it is real, you know? It occurred to me that I have to die every night. Every night. And it’s like this momentum that builds towards it and it’s wild. What helps is that I feel absolutely safe and protected by my cast and my director, and I believe in the story we’re telling. You know I think it’s the most important play on Broadway right now.

Is believing in the importance of the project something that is necessary for you?

For the most part, yes. But what I believe in and connect to, there’s a big range. It could be something like “Knucklehead” or an action revenge movie. And I have to in order to get behind the character, because so much work goes into doing that, even if it’s like a guest star on a show, so much work goes into it.

If you don’t want to be there I imagine that will be reflected in the work.

But for me, if I don’t want to be there, I still have to deliver something because it’s my name on the line and it’s part of a body of work that I’m building. I did a project, which I will be very vague about, that was a shit show. I’m pretty sure it was a money laundering thing, it was crazy. The other actors, the crew, everyone was like, “Oh, this is not good and it’s getting worse. These people don’t know what they’re doing and we’re all suffering for it.” And, still, when the camera came on, I had to deliver something real even though the circumstances in which I was working seemed very unreal.

Most people will know nothing about the background of the production. All they will see is you on the screen and your name in the credits.

Exactly, but I’m pretty certain nobody will ever see that project. [laughs]

I want to backtrack a little. You had already been acting for a few years before you came to Brooklyn, right?

I was actually an extra on “The Wire” first and was living in Maryland when I did that. And then when I [got the part of] Chris, I was living in New Jersey and would go back and forth. After shooting the third or maybe the fourth season I moved to New York.

You initially lived in Harlem?

Yeah, and I was very determined not to be one of those lemmings, fleeing Harlem and going to Brooklyn, the new generation of hipster kids or whatever. I said, that’s not me. I always prided myself for never living under 116th Street.

What brought you to Bed Stuy?

You know, in New York, you have to move around a lot for different reasons: price, roommates, landlords, infestations, all kinds of stuff. So I had to make another move and I looked at apartments all over Harlem. I loved Harlem, but it wasn’t working out. And then I saw something online, I think it was on Craigslist, and I said, ‘Hey, I’ll check out this one spot.’ Visually it looked pretty cool. It was in Bed Stuy and I ended up taking it. And it was the only place I looked at in Brooklyn before I moved here.

How long were you there?

For about a year before I had to move, because the roof was leaking and there was mold. I couldn’t sleep because it was burning my eyes. But I loved the apartment, so I looked all over. At this point I knew I wanted to stay in Brooklyn.I ended up renting a place down the street from where I was living and I was there for years, and then I decided I wanted to buy something. And at that point, I knew that Bed Stuy was going to be my home. I didn’t want to live anywhere else.

What connected you to Bed Stuy?

The history of the people, the history of the art and movements here, the history of the buildings. I fell in love with all of it, absolutely. I’d walk around and friends of mine who are architects, or just people who have lived here for a while, they would just teach for hours, teach me about the buildings, about the architects who came over from Europe, the designs block by block, the styles in which they practice and the people that lived in those buildings. I loved it because they’re all like stamps in time. And then also there were community events, and people said hello to one another in the streets. There’s streets named after Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey. I was like, all right, I can rock with that.

At the same time, the neighborhood is constantly changing.

I can be away for a week or two months and it’s different. It used to be that you’d be on the train and as you go past the Clinton-Washington stop all the white people would get off, and then all the black people would stay to the later stops. Then that started to change. And more and more white people stayed until later stops. I remember the first time I get out at my stop and a white dude was outside and asked me for swipe to get in. I’m like, it’s over. You’re asking for a swipe to get in? Here. You can take Bed Stuy. It’s yours. Like that blew my mind.

Do you see yourself staying in Bed Stuy?

I love it here. I still feel lucky to be here. There’s a few other places that I love, like London. I could see myself there for a few years. But it’s hard to live anywhere else once you live in New York. It’s just in your system.

How did you get into furniture design?

It started out as me appreciating an antique piece and then, sometime after, it turned into me trying to save this antique piece. That was maybe three years ago.

What’s the process for how you put together the pieces?

It’s finding a piece and trying to think about where this piece has been, who owned it, what life it lived before. And then what it needs now, and what looks can possibly complement it or add to its story. And we’re getting these fabrics from all over the world and the stories that I got tracking them down, you know, being in markets in Lagos and negotiating with these women who were really tough. All these stories, it’s amazing. I love it because of that, because now I have a story about when I got this fabric, I have a story about how I ended up making this piece with people I work with who carry out my designs, and then, hopefully, people finding it to bring home and add to their own story.

You’re collecting stories but also creating new stories.

That’s the goal: add to the story and then put it out there. And sometimes it’s hard because all those pieces are like my babies. So my friends are like, “You should try selling these things.” And I’m like, “I don’t know, is it going to go to the right place?” I want people to have them who appreciate them. For me, these are all pieces that should be handed down to later generations. That’s how they came to me, whether they’re taken care or not taken care of, people had them. These pieces outlived us and hopefully will continue to outlive us.

Aside from Lagos, where else have you gone to source these fabrics?

I was in South Africa shooting something a few years ago, searching for fabrics. I was in London, shooting a movie, “All the Devil’s Men,” searching for fabrics. And then I went to Paris to visit a friend, bought some fabrics there. I’m always looking. Even if you’re not going to get anything, I learn so much from people telling me things, going to these small towns, the small shops. I love talking to people. I’ve been to some very rural towns where they don’t really see a lot of people who look like me and they may or may not have feelings about me walking into the shop. And all of a sudden you’re like, connecting over this vintage piece, and we end up spending hours talking. I remember this one place in particular in Oklahoma. I was there until the store shut down. It was run by this older rough dude, and you wouldn’t imagine us just connecting and him just teaching me so much. I asked him questions and then, actually, I went back.

Is highlighting those connections also part of your Liberated People project?

It’s interesting because at the time I had been a part of different protests around the world and these things are important to me. One thing I noticed was that I’d be in these different countries or these different cities protesting with people who look different and spoke several different languages. But they’re all for the most part protesting for the same things: human rights, their democratic right. I also felt like these groups felt that they were alone in their struggles. Like, only people of this ethnicity or this gender or in this country suffered this way. Having had the opportunity to be able to be in these places I saw this is what we have, you have, in common and I wanted to create something that reflects that, to help shine a light on that. And the clothes are just a conversation: We all have liberation dates, so it’s about diving into those things and celebrating our differences, a cliché that’s true. We have far more in common.

The acting, the furniture design, the activism — do you see deeper connection between all these pursuits?

I didn’t but other people have pointed it out and I’ve thought, “I guess there is a connection.” In my mind, I’m just doing the things that appeal to me, trying to make a statement or express something. For me, it all comes down to creation. They’re all different ways to create a story.

And, like we talked about before, to be able to pass on those stories.

Right, these are all ways to pass on stories, to pass on something. But I didn’t think of it that way. Now, when people say that, it’s like, “Oh, that’s crystal clear. Of course!”

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- FiveMyles Gallery Connects Crown Heights

- Greenpoint Author Melissa Rivero’s Journey Through the Past

- Jonathan Lethem Comes Home

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment