EPA Says Fast-Tracked Testing Shows Clean Air at Greenpoint School Despite Meeker Avenue Plume

Federal environmental regulators found the air inside P.S. 110 in Greenpoint is clean — putting to rest the worries that students were inhaling toxic chemicals from a federal Superfund site underneath the school grounds.

The air at PS 110 The Monitor School in Greenpoint is safe and largely uncontaminated by the Meeker Avenue Plume, the EPA has found. Photo by Nicholas Strini for PropertyShark, 2020

Parents and students at P.S. 110 in Greenpoint are breathing a little easier, knowing that federal environmental regulators found the air inside the school is clean — putting to rest the worries that students were inhaling toxic chemicals from a federal Superfund site underneath the school grounds.

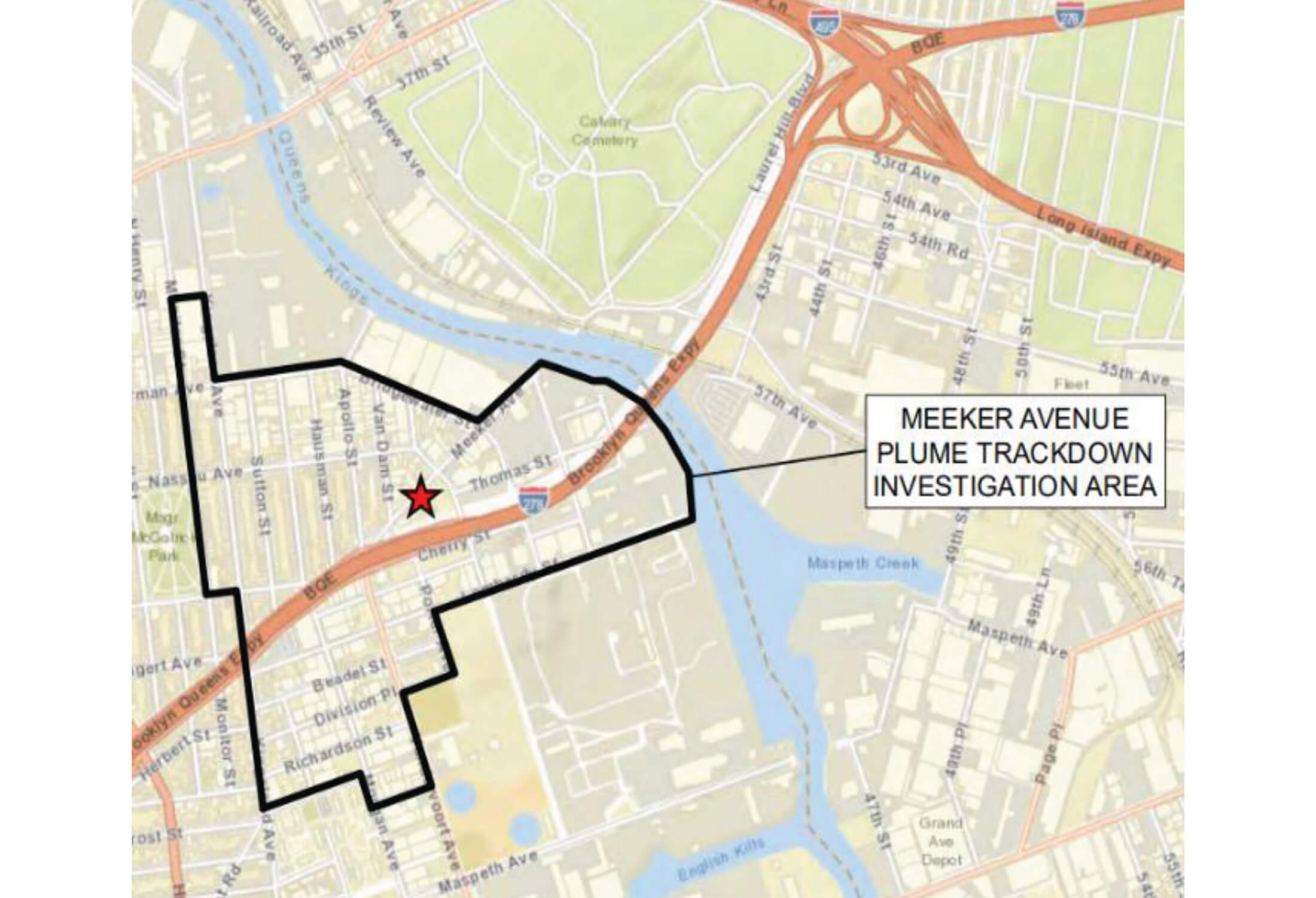

P.S. 110 The Monitor School sits atop the Meeker Avenue Plume, which sparked fears that hazardous materials could be seeping through the ground and into the building near McGolrick Park, which would pose a risk to the air quality inside the school.

But the federal Environmental Protection Agency found that it’s unlikely that Chlorinated Volatile Organic Compounds had in fact infiltrated the building, Remedial Project Manager John Brennan explained at a May 3 meeting.

“The EPA’s determination was that no further action is needed at PS 110 at this time,” Brennan said, adding that the agency uses “health-based screening criteria” developed to protect sensitive populations — including children and pregnant women — to evaluate test results.

Public concern pushed the agency to fast-track testing at the elementary school, which sits just inside the western boundary of the Meeker Avenue Plume Superfund site. Soil and groundwater within the Plume are heavily contaminated with carcinogenic CVOCs, which can evaporate and work their way into buildings in a process called Soil Vapor Intrusion.

State and federal officials have been testing indoor air quality in buildings within the Plume for years to protect residents and help determine the exact size and makeup of the site, and, for now, the EPA is focused on residential buildings.

P.S. 110 was last tested — and found to be safe — in 2008, but after the site was designated a Superfund last year, residents said they wanted updated tests — especially because the school’s 486 elementary-aged students spend time in the building’s basement, where CVOCs would be most concentrated.

Results show little reason to worry

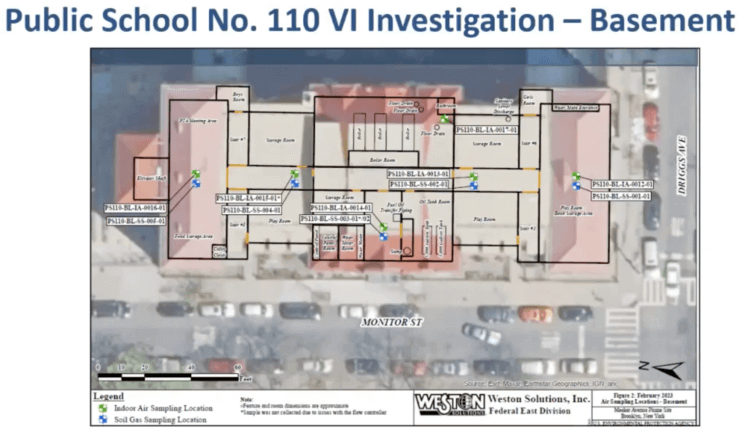

In early February, the EPA set up 17 indoor air quality monitors in the school’s basement and on the first floor, Brennan said, and drilled five soil gas monitors into the basement floor. The agency asked the school to temporarily remove any “background” sources of CVOCs – like paint and glue — so as not to interfere with the readings, and had the doors closed with the HVAC systems running as they would on a normal school day.

Two readings — from the main office and a classroom on the first floor — came up just above the EPA’s “screening level” for 1,2-dichloroethylene — but well below levels that could harm human health or require remediation.

The EPA’s residential screening standard for 1,2-DCA is 0.108 micrograms per meter cube – roughly equivalent to 0.108 parts per billion, while the “action level,” which would require a response or cleanup, is 7.3 micrograms per cubic meter. The first-floor classroom had a level of 0.122 micrograms per meter cube, while the main office had a reading of 0.197.

“Screening levels” can indicate that a particular area needs further investigation, but do not necessarily present a threat to human health, even with long-term exposure, said EPA Human Health Risk Assessor Nick Mazziota.

The EPA’s screening tools are extremely sensitive, Brennan explained, comparing the air in a room to a swimming pool full of a billion marbles. If all of the marbles were white, except for one, which was green, the tools would be able to detect even part of that green marble, according to the project manager’s analogy.

Brennan said that since concentrations of the chemical were higher on the first floor than in the basement, it’s probable that the 1,2-DCA wasn’t coming from the Plume at all, but from background sources like cleaning equipment and paint, and further investigation isn’t needed.

“The presence was likely due to everyday products that have been used in the school,” Brennan said. “EPA assessed that the detections are not indicative of health concerns for students and or staff.”

Some CVOCs are used in cleaning products, spray paint, glue, and products like White-Out, the project manager explained. The level of those chemicals in everyday goods is not high enough to present a hazard to users, but can still be picked up by the EPA’s sensitive equipment.

“The screening levels and the action levels are really meant to be health protective,” Mazziotta said. “The screening levels at the school were based on residential exposure, and those levels are calculated to be protective of someone who could be exposed 24 hours a day, 350 days per year, for over 20 years.”

While the results do not present a risk to students or staff, the agency will continue to study the data and will be carrying out soil vapor, groundwater, and soil testing in the area in the near future, Brennan said.

“If there is any additional sampling that is needed or anything that we find that would lead us to believe that additional testing at the school is needed, then EPA will do that,” he said.

Testing continues across Greenpoint

In March, the agency also took samples at all 11 buildings at the Cooper Park Houses NYCHA complex right across the street from the Plume. While the development sits just outside the existing boundaries of the Superfund, those boundaries are not set in stone, and testing will help to determine exactly where contaminants have settled.

Most buildings at Cooper Park Houses have common areas on the ground floor and in basements, Brennan said. The EPA tested air in the senior center, the community center, the early education center, and more.

The results of that testing are not yet available – the data is still being analyzed and won’t be released until it’s been vetted and finalized. As soon as the information is ready to be shared, the agency will meet with NYCHA and residents to discuss the results and any further action, if it’s needed.

Remedies for soil vapor intrusion vary and depend on the conditions of the structure and the severity of the intrusion. In some cases, simply sealing up cracks in the foundation is enough; in others, the EPA will install mitigation systems that prevent air from rising into a building.

Over the next few months, the agency will continue to test soil, water, and air in the nabe. This summer, more than 300 existing wells will be used to test the groundwater across the Plume. Come fall, the EPA will resume indoor air testing at homes and residences.

Ten homes were tested in the winter of 2022-23, but those results will be shared privately with homeowners and tenants – not with the public.

On May 10, the Meeker Avenue Plume Community Advisory Group will meet for the first time at the Cooper Park Community Center – all interested residents are encouraged to attend as the group begins their work to help the EPA plan and carry out their cleanup.

Editor’s note: A version of this story originally ran in Brooklyn Paper. Click here to see the original story.

Related Stories

- EPA Gives Updates on Testing, Risk Assessment for Meeker Avenue Plume Superfund Site

- Environmental Activist Irene Klementowicz Remembered as Champion of Greenpoint Causes

- Contaminated Air and Groundwater Lead to Meeker Avenue Plume Superfund Designation

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment