Walkabout: J. Mason Kirby – Brooklyn's Elephant Architect

Architects are often remembered, not for who they were, but for the buildings they designed. Here in Brooklyn, names that had been lost for generations are now almost household names again, due to renewed interest in the neighborhoods they designed in, and, hopefully, from the attention given to them by myself and other writers and…

Architects are often remembered, not for who they were, but for the buildings they designed. Here in Brooklyn, names that had been lost for generations are now almost household names again, due to renewed interest in the neighborhoods they designed in, and, hopefully, from the attention given to them by myself and other writers and lovers of their architecture. But not even the greatest of them, those builders of skyscrapers, cathedrals and mansions, can boast of not one, but two buildings that have been classified into the rare category of “zoomorphic architecture.” J. Mason Kirby is one of those lucky few, blurring the line between architect and builder. When he wasn’t doing that, he was designing eye catching and inventive rows of houses here in Brooklyn.

Joseph Mason Kirby was born in New Jersey in 1837. By the time he was in his twenties, he was living in Philadelphia, and was listed in city directories as a carpenter, and later, by the 1870s, a builder. His experience in both crafts may have landed him the job that would earn him a place in architectural history: novelty division. In 1881, he was hired to build a huge, 65 foot high elephant building in South Atlantic City. That city is now called “Margate”, and is a resort town on the Jersey Shore.

The 65 foot high elephant, called “Lucy,” was constructed with a strong wooden frame, covered in tin. It had stairways and rooms with windows, and one entered from the hind leg and exited from the front leg. The highlight of the elephant was the view from the “howdah,” the canopied seat on top of the elephant. From there, one could see for miles in every direction. Lucy belonged to James V. Lafferty, Jr., who built the structure as an advertising tool for his real estate developments. One could see his offerings from the howdah, and it was a huge success. Lucy was quite a complicated and technical feat, and once figured out, Lafferty wanted to build more of them. He applied for, and won the patent for “a building in the form of an animal,” in 1882.

The records and newspaper reports are rather fuzzy as to who actually designed Lucy; J. M. Kirby, or another Philadelphia architect, William Free. Since architects did not have to be licensed at that time, the classifications of “architect” and “builder” could be almost interchangeable. Some sources credit Mr. Free for the design, while other newspaper accounts credit Mr. Kirby. At any rate, Lafferty and Kirby saw the possibilities for elephants like Lucy wherever amusement and public parks could be found that could afford one, and they formed a company, and began looking for the next place to put an elephant.

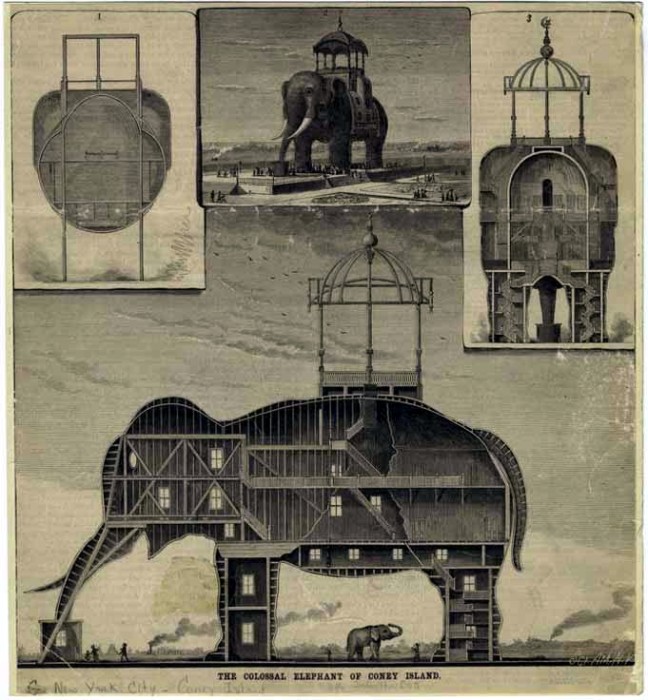

What better place to put a colossus of an elephant but Coney Island, and in 1884, that’s what was planned, a much larger 122 foot high, 150 foot long elephant for Coney Island appropriately named “Colossus.” In 1884, 263 men worked 120 full days to finish it. Colossus stood on Surf Avenue, just opposite the Iron Pier, a prominent tower at the edge of the ocean. It was practically across the street from the terminal where all of the public transportation to Coney Island was based: the trains, trolleys, roads and steamboats. Even if you weren’t in the least bit interested, there he was, as prominent an attraction as any of the amusement parks or attractions.

The building was used as an exhibit hall, and had 31 rooms named for different parts of the body. There was a Stomach Room, a Shoulder Room, Throat Room, etc. Like Lucy in Margate, Colossus also had a howdah roof, with a covered observation stand where visitors could catch the spectacular view. It was a fantastic 50 mile view of the ocean and bays, Brooklyn, New Jersey and even Manhattan. Colossus was designed to look as if he were feeding, with his trunk extended to a “bucket,” which was actually a small building itself. Like Lucy, one entered in the back leg, and could exit from the front, after going through all of the levels and rooms.

Colossus and Lucy both were engineering marvels. When Colossus was built, Lafferty handed out publicity sheets touting the building’s specifics. Colossus contained 3, 500,000 linear feet of lumber, 11,000 kegs of nails, and 12 tons of iron bolts to construct his frame and interior rooms, and 57,000 square feet of tin to cover him with his “skin”. The elephant also had 65 windows to take care of ventilation, and was lit by 25 electric lights, still quite the novelty at the time. Colossus was built to withstand strong winds, rough winters and sweltering summers. Kirby knew wood, and engineered the superstructure of the elephant to give where necessary, and hold. The ventilation assured that the wood did not rot, even though it was exposed to the humidity and potential damage from the salt air. The design was so good, that Scientific American magazine published a cover story about Colossus, touting the engineering and building mastery necessary to build such a wonder, and to anchor it so well in the sand.

James Lafferty and J. Mason Kirby couldn’t have been more excited by the possibilities. In his advertising materials, Lafferty told potential clients that he held the only government patent for building animal buildings. He had the two elephants, and could build another anywhere, but the client was also free to choose another animal. He envisioned birds, fish, or other animals. The potential was there for the hiring. J.M. Kirby, for his part, was written up in “Building Age,” a trade magazine in 1885. There, they teased him about his new specialty and noted that he had new business cards printed up which labeled him an “Elephant Architect.” I suspect Kirby felt that any free publicity was good publicity, and took the ribbing with a grain of salt.

Unfortunately, Colossus was a wonder, but not a money maker. After the initial thrill was gone, it loomed over Coney Island, and was a local landmark, but not a popular paying attraction. The view was fantastic, but there were at least three other iron towers on Coney Island that offered a similar view and vista. The exhibits inside must have been pretty meh, because I couldn’t find anything that actually said what they were, other than an exotic “bazaar.” It cost twenty-five cents to go in, a lot of money at a time when many rides, including the train to get there from other parts of Brooklyn, were only five cents.

Lafferty sold Colossus to a Philadelphia management company and moved on. Another elephant was built on Cape May, but that one was heavily damaged in a hurricane, and torn down. Back at Coney, Colossus started to look a bit seedy. New and larger attractions were built nearby, and the elephant suffered the fate of most Coney Island attractions. People said, “Been there, done that;” they always wanted something new. The bazaar closed, and the elephant became a boarding house, which must have been a logistical nightmare, even with a central bathing room somewhere, and perhaps a water closet on each floor. By 1896, Colossus was mostly abandoned, and on September 27, 1896, someone put him out of his misery; Colossus caught fire and collapsed into the sand.

Today, Lucy still stands in Margate, protected by landmarking and National Register status. It is the oldest example of zoomorphic architecture in the country, still a very small subset of vernacular architecture. J. Mason Kirby would still be in a class practically by himself. After finishing the construction of Colossus, he moved back to Atlantic City, but then came to Brooklyn. Another phase of his career was about to start.

In 1887, he designed and built a group of 30 houses in what is now Brownsville for developer Frederick W. Hammet, and his brother Walter. He moved into one of the houses in 1889, with his family, and designed his other Brooklyn houses from that location. Those houses, which were on Sackman and Powell Streets, and Glenmore Avenue, unfortunately, no longer stand. He then designed a row of houses on Park Place, between Franklin and Bedford, begun in 1889, and finished in 1890. Those thirteen houses were in the Queen Anne style, and were 18 feet wide, designed in three different styles in a symmetrical A-B-A-B-B-C-A-C-B-B-A-B-A pattern. They are classic Queen Anne’s with rough cut stone ground floor, with brick above. The “A” houses have steep pitched roofs; the “B” houses are the plainest of the three, with flat roofs, while the “C” houses have rounded gables. There are other stylistic features inherent to each style, as well.

The Park Place houses were quite successful, and sold well, so Kirby was eager to try again, this time designing two groups of row houses in the eastern part of Stuyvesant Heights. He designed

Fifteen Queen Anne style houses on Decatur Street, between Howard and Saratoga Avenues, and another ten house group on Bainbridge Avenue, a block away, between Saratoga and what is now Thomas S. Boyland Street, in 1891. The Decatur Street houses are the topic of today’s Building of the Day, so please read up later, I promise, it will be interesting.

After completing these houses, he decided to take some time off. He and James Lafferty and their other partners wanted to build more elephants, and they took their designs to Chicago. They wanted to raise enough money, half a million dollars, to build the ultimate elephant building at the World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893, in Chicago. Unfortunately, that did not come to pass, and it was never built. Kirby came back to Brooklyn, and in 1894, built a group of storefront and flats buildings on Central Avenue, on plots of land that he owned. Those buildings are now gone, as well.

In 1899, Joseph and his wife, Anna, and their four children moved to Manhattan, where they lived for twelve years, settling down in Harlem, while Kirby designed and built houses in the Bronx. There, he did a little designing, some building, and some buying and selling of property and houses. But once in your blood, Brooklyn becomes a siren call, and in 1911, they moved back to Brooklyn, settling in Bedford Stuyvesant, on Greene Avenue. Joseph Kirby lived there until his death in 1916. Since he was a Quaker, he is now buried in the Friends Cemetery in Prospect Park.

Today, Kirby’s eclectic housing stock is looking at landmarking. The Park Place houses were landmarked in 2012, and the Decatur and Bainbridge houses are part of what is being called Stuyvesant East, a very popular neighborhood right now. Only aficionados of Coney Island history even know about Colossus, and a visit to Coney Island will give you no clue as to its location. The most hyped and remarkable building on the beach is less than a memory. Fortunately, we still have Lucy, down in Margate. For a 132 year old folly, the old girl is doing well. She even survived Hurricane Sandy with only minor damage. Kirby knew his stuff. Funds were raised to make repairs, and she still is a curiosity and thrill for beachgoers.

(Above photo of Lucy, in Margate, NJ via Wikimedia)

This was an awesome read Thanks MM….