A Developer and Artist Duo Are Building Creative Hubs in Brooklyn. A Flatbush Church Is Next

Audrey Banks and Joseph Banda have formed a somewhat serendipitous partnership that is making ground in adaptive reuse: converting historic buildings into affordable living and working spaces for artists and activists.

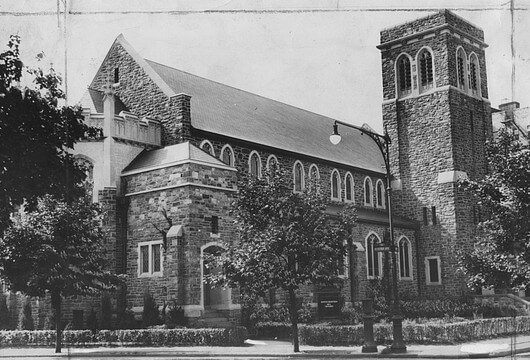

The sanctuary of the Flatbush Presbyterian Church. Photo by Neesmith Onzeur

They seem odd bedfellows: One, a young creative determined to build affordable spaces for artists, the other, a real estate developer with a number of residential buildings across Brooklyn.

But Audrey Banks and Joseph Banda have formed a somewhat serendipitous partnership that is making ground in adaptive reuse: converting historic buildings into affordable living and working spaces for artists and activists.

One of the most striking things about the partnership is that it could be a business model that works more broadly to preserve neighborhoods and affordability. Banda — who is behind Ranco Capital, which currently owns and manages more than 800 apartments, including Park Slope’s The Deermar, and thousands of square feet of commercial and industrial real estate throughout the city — isn’t on some kind of heroic mission to save the city’s historic buildings, nor provide for creatives.

As he puts it, he is a businessman. He is buying properties and redeveloping them in ways that make the most sense financially — sticking with existing zoning and occupancy rules and foregoing lengthy public review or conversion processes, but notably, he also places a lot of weight on context.

“Sometimes the right use is the original use,” he said. “If the original use doesn’t make any sense I wouldn’t do it, but you have to think out of the box. If you’re going to buy a church, there is a use for the church; it doesn’t have to be the same use as it was 100 years ago, maybe there’s a new religion,” he laughs, “but there are other uses.”

Meanwhile, Banks, who is determined to re-create affordable artistic collaborative spaces of days gone by, finds those other uses for the buildings so they can be rented by local creatives.

It’s a win-win: building saved, building used.

Their first project was the 168-year-old wooden villa at 70 Lefferts Place, which is a home to around 10 artists who use it as a space for collaboration and creation. The second is an artist residence in a 19th century brick townhouse at 92 Lafayette Avenue.

But their current project is their most ambitious yet: The conversion of a 14,570-square-foot, 124-year-old Flatbush church into a community arts and social impact center, complete with more than 250 shared co-working spaces, multiple performance venues, a cafe and retail store, food pantry, a gallery, and recording and artist studios.

The Flatbush Presbyterian Church, located at 494 East 23rd Street, was built in 1898 on land donated by Flatbush resident Mrs. Benjamin Stephens, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported in 1897. Architect John J. Petit created the early English Gothic-inspired structure to include a basement with a large recreational space and kitchen, and a first floor with a meeting room and a women’s parlor.

In the late 20th century, the church, which most recently housed the Flatbush Church of the Redeemer congregation, fell on hard times financially and in 2019 was sold by the Presbytery of New York to Banda (under an LLC) for $3,338,300, public records show.

Immediately, the community feared the worst and started an eleventh hour campaign to landmark the building; however, no formal designation eventuated. Banda is the first to admit those fears were warranted, saying he bought the church with the intent to knock it down and build townhouses: “I’m a developer,” he added. The property was already zoned for residential use, development is as of right, and all that Banda needed to do to prepare the land would be to apply for a demolition permit, he said.

But after significant community outreach to save the church and use it as a community space, he took some time to reflect. “If someone created something 100 years ago and it worked for whatever reason they created it for, and there’s another use for it, just knocking it down and building townhouses is definitely not what they intended when they built the church and it doesn’t feel right to me,” he said.

So he turned to Banks, the collaborator he had met years earlier when she worked part time at Bushwick’s Subway realty company, and tasked her with finding a way to reuse the space.

Banks, 28, an artist and coder who runs artist collective AllinOne with co-founders Ameya Biradavolu, a social worker and director of programs at Harlem-based We Are Not Afraid community resource center, and Miles Bolton, an environmental scientist, said the overarching goal of the group is to create spaces for arts and activism, “basically what whole neighborhoods used to be in the ’70s and ’80s and before New York’s price point became untenable.”

“Now most people are incredibly spread out to the edges of Brooklyn and the city because the cost of living is so high,” she said.

The way AllinOne addresses this is by renting buildings, so far solely from Banda, and transforming them into creative places for co-living and co-working, where residents and members apply to live in or use the spaces and are vetted by the collective, and then tasked with actively working together on projects. Those residents pay to live in and use the spaces: At the house at 70 Lefferts Place, bedrooms range from $680 to $1,250 per month and studios are available for between $360 to $1,360. AllinOne then pays Banda $16,000 a month to rent the building.

Artist Ana Curtin, a former tenant who is 24, said the arrangement was perfect for her: someone in New York City for a short time who enjoyed a social and collaborative environment. “I think it really depends on what kind person you are, you have to be OK with it being messy and chaotic at times, it’s impossible to avoid in such a big house,” Curtin, who lived at the house between September 2021 and May 2022, said. “If you’re Type A, it’s probably not the environment for you.”

Curtin said the tenants had a Discord chat to communicate and make plans, and there was a chore chart to give structure to taking care of the house. When issues arose with the building, which she said inevitably happened in such an old house, tenants usually dealt with Banks and the collective, as Banda was harder to get hold of.

At 92 Lafayette Avenue — an SRO, according to DOB and HPD — monthly rents range from $875 to $2,000 (which is for the largest unit the collective operates). Banks said currently the building is home to five artists and activists, and it includes a backyard with a greenhouse built by the mutual aid group and partner Bergen Green Space, and a small roof deck.

At all the spaces, the collective is building on a co-creating model, Banks said, “where people are sharing resources, exchanging skills and really learning and collaborating with each other and trying to establish a platform that specifically does that rather than just putting people in a room and hoping they speak to each other.”

The church, she said, will follow the same collaborative model as the previous properties, but without the living spaces.

Together, Banda and the collective are retrofitting the structure to include multiple rooms and areas designed, Banks said, to be used for creative and social impact work. That includes adding foldable desks to the pews in the main nave for co-working, along with creating a small performance area that Banks hopes also can be used for weddings. The collective is also working with retail platform The Canvas — which helps emerging, sustainable brands share physical storefronts — to open a retail store that features local designers. The Canvas is also providing tech support and consulting services on financial projections and project ideation.

The first floor will also include a cafe and a yet-to-be-decided third space (Banks said AllinOne is in talks with a nail salon, but has had some requests for a bookstore).

In the cellar, there will be more desk space and the existing accessory kitchen will be used as a restaurant and food pantry – likely run by local nonprofit Soul Food to the People – and also a kitchen for members and the public.

Kiana Muschett-Owes, who runs Soul Food to the People and Katie O Soul Food Restaurant, said she met Banks near the start of the pandemic when AllinOne invited her to use 70 Lefferts Place as a place to cook meals and have food delivered and packed for those in need. When Banks told her about the church, Muschett-Owes saw the potential for the community space and immediately wanted to get involved. “I have a big vision, and every day it gets bigger and bigger,” she said.

Muschett-Owes said she wants to set up a Katie O’s restaurant in the church that will fund a weekly or biweekly community food pantry, where those in need of hot meals can come in for everything a sit-down restaurant experience offers, without the price tag.

“You’re seated by a host and get a menu, you choose your food items, the food is brought out to you, everything except having to pay — it’s done with dignity and respect,” she said. “Often for people already not in a good place facing food insecurity, the dignity and respect is removed, so for me having that is a big deal.”

Muschett-Owes also has a vision for bingo nights for seniors, and mental health and stop the violence workshops.

In the basement, there will also be a larger performance venue with a full stage, recording and podcast studios (which Banks said there has been large demand for locally) and a classroom.

Then, on the second floor, there will be artist studios and a gallery space, and the bell tower will house a conference room. “It’s one of the coolest parts of the space, you get to go up this winding staircase and be in this beautiful castle-like room to discuss or use it for whatever,” Banks said.

For CaribBeing founder Shelley Worrell, who was born and raised in Flatbush (and lives nearby), having the church used in such a multifunctional and multiuse way is fantastic, she said, and she loves the model. She said there is a huge need for art studios in the area, and is excited to see how the concept rolls out.

But she did question how much AllinOne and Banda are really reaching the greater Flatbush community, and whether there is a lack of diversity, equity and inclusion in the planning. “This is a very Caribbean neighborhood, and this is in very close proximity to Little Caribbean.”

“How is this project really appealing to the broader neighborhood and demographic, not just those benefiting from it but those included in the opportunities of the co-working spaces, maker opportunities, art studios and even food offerings,” she said. “It feels a bit outsider to me, which is fine — I think it’s OK for people to come in, but I think it’s really important they include the community that has existed for a long time.”

Imani Henry of Equality for Flatbush seconded that sentiment, saying there is already a huge artistic community in Flatbush that could be involved in the planning and execution of the project, and he invited AllinOne to reach out to those groups and people. “If we come from a place of true integrity and love, if we want to see art and culture survive, just stop, take a moment and look: Are you surrounded by people who are just like you? Who look like you? Are there people that are older and younger than you?”

Banks said she totally agrees with Worrell and Henry, and it is paramount to her that community members and existing groups are involved from the outset in building the space and making sure it provides exactly what the community needs and wants. She added the collective has only just started taking the project public, and is now doing extensive outreach to connect with existing groups and individuals to bring them into the development plans. On Juneteenth, Muschett-Owes and Biradavolu (a Flatbush resident) will host a community engagement block party, the collective’s first outreach event.

“At the end of the day this is a community center, we’re not going to do it without really working with existing groups, collaborating with the community and servicing the existing needs,” said Banks.

Local fashion designer Stacey Berry, who has no connection to the collective, has rented studio space in the past and had to go as far afield as Greenpoint. “I looked around locally and couldn’t find anything. There’s definitely a need in the community,” she said, adding she posted in local Facebook groups for leads and just found others also looking for space. “There was talk a couple of years ago about artist spaces coming up in the Caribbean Market, but that’s now commercial and residential.”

In turn, Berry said she rented a bigger living space to bring her studio home. She and her husband, who is also an artist, would definitely be interested in renting space at the church, even just to go as members and use communal spaces, she said.

“The social aspect is definitely a draw, being able to meet your neighbors and fellow creative collaborators to see projects through. It’s always good to be around creative people, and it’s such a residential neighborhood that to find a space to mix with other artists would be a great option outside of a bar.”

For Berry, price, size of the spaces and the hours of operation would be the determining factors on whether she rented space at the church, but said the prospect of moving her work out of her home (but very close to it) was enticing.

Banks and Banda say construction on the church is slated to start in coming weeks; however, the pair is still waiting for DOB permits to be issued. Currently, the DOB has raised objections to the plans that need to be addressed before permits are issued, according to DOB records, but Banks said the department only raised one objection that was made in error, and she and Banda expect that to be resolved soon.

With the significant interior work to be done, the project could realistically take a year to complete, although Banda and Banks were reluctant to make any estimates. Once open, with 250 co-working spaces, commercial kitchen, cafe and retail stores, and artist studios, the enterprise could potentially collect around an estimated $45,000 a month in rent — all of which will be managed by Banks and the collective. Banda stressed numbers were still being finalized, as the budget for the project has grown and there are a lot of moving parts, but said that figure could be in the ballpark.

As with the other properties, Banda will set the rent for the church, and the collective will pay him. The collective sets the rents for tenants, which Banks says are able to be kept below market rate due to the collective taking out the full lease for the building. The collective then takes a small cut of the rent it charges tenants, before paying Banda his set amount. Banks says the collective also gets some of its operating budget for running the spaces from ticketed programming.

All in all, it’s a large undertaking for AllinOne, but Banks says she’s ready for it. Currently, she is fleshing out the pricing for members, but said there would definitely be tiered rates and the space is being specifically designed for the local community and individuals and groups doing creative and nonprofit work, so the priority is to make it affordable. A website for the church went live last week to attract people interested in co-working and studio spaces, and also the community can send feedback on what they’d like to see at the church.

“We really want to cater to the needs and pursuits of the internal members and those of the surrounding community, so those spaces might transform over time,” Banks said.

Banks said the buildings that house creative enclaves play a large role in how they operate, and that restoring and reusing historic New York buildings can help re-create the creative hubs of days gone by. “It’s adapting this old beautiful architecture for a creative use and also preserving that at the same time so they’re not demolished or left vacant and empty,” she said.

“We’re hoping to get this model really airtight so we can copy and paste it in other locations starting with Brooklyn, but maybe even going outside of New York – this problem we’re tackling definitely exists in other metropolitan cities as well.”

Harry Bubbins, who was involved with the group Respect Brooklyn, which petitioned for the church’s landmarking, said the plan was “all too rare good news that shows community engagement and responsible property ownership can align for visionary outcomes.”

He said Landmarks Preservation Commission made a shocking decision by refusing a hearing on the “architectural masterpiece,” but that engagement by the local community ensured the preservation of the building. He said he has faith that AllinOne will be “excellent stewards of the 1898 Gothic building, activating it in modern and creative and accessible ways for Flatbush.”

“Critically, a knowledgeable and responsible property owner with awareness that money can still be made without demolition was involved here,” Bubbins said. “Adaptive reuse is better for the environment and allows affordability goals to be met for housing or creative spaces. We commend everyone involved in this win-win situation and hope it becomes an official landmark with all the associated tax credits for repairs and investment.”

And would Banda get behind the effort to replicate if all goes well? “Absolutely.”

“I could see myself purchasing other buildings like this at a much cheaper price, because you could keep them and implement such a good use,” he said.

Related Stories

- The Grand and Mysterious Willoughby Avenue Mansion of Grocer Jacob Dangler

- One of Bushwick’s Oldest Congregations Proposes Deal With Developer to Save Its Distinctive Church

- Artifacts From Soon-to-Be-Demolished Historic Boerum Hill Church Go up for Sale

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment