Extensive Construction in Gowanus Forecasts a Very Different Neighborhood Ahead

Change is coming quickly to Gowanus, and a stroll down Nevins Street reveals the extent of the transformation.

Looking north up the Gowanus Canal. Photo by Anna Bradley-Smith

Gowanus, an industrial and low-lying neighborhood, has been undergoing a sudden and sweeping transformation over the past year and a half. Swathes of low slung 19th and early 20th century brick industrial buildings have been demolished. In their place, ubiquitous on many blocks, are active construction sites ringed by green construction fences. Walls are starting to rise on a handful of developments, and at least two sets of towers and a nine-story apartment building have topped out.

The dramatic contrast between mid-2022 and now, the geographical size of the transformation, and the speed at which it’s happening isn’t truly felt until you step foot in the blocks bordered by Carroll, Baltic, and Bond streets and 3rd Avenue, where you can’t turn a corner without seeing a green construction fence. In the very near future, it’s likely there will be at least a dozen new buildings with hundreds of units each, including a handful reaching up to 29 stories.

While still in its early stages, the work forecasts the wholesale replacement of the neighborhood. Advocates for increasing the city’s housing stock say drastic change like this is needed citywide to address housing affordability, but some locals say the scale of change could result in the loss of the neighborhood’s character and history as well as vital industry in a way that could have been avoided while also helping to ease the city’s affordable housing crisis. Many, regardless of where they stand on the development, have questions about the safety of current and future residents given the environmental and infrastructure issues in the neighborhood.

Then there’s the question of whether the city will stick to the commitments it made as part of getting the rezoning passed, including the large-scale investment in local NYCHA developments and the construction of the long-in-the-works 100 percent affordable Gowanus Green development (formerly Public Place).

Development starts after delays

While development was planned for and expected after the 2021 rezoning, the “explosive” (in the words of one local) amount that has recently arrived in the heavily polluted neighborhood is still shocking to community members.

“It is very sudden, it’s everywhere, and people are losing their skylines…It really started in the last year, and now it’s just these behemoths everywhere. To be honest it’s a little sad to go down there,” Joseph Alexiou, a Gowanus historian and tour guide, said.

Jamie Courville, a filmmaker working on a documentary about change in the neighborhood called Gowanus Current, said around the fall of 2022 buildings started to come down. Despite knowing what was coming, “it just sort of took your breath away…just physically seeing it happen was shocking.”

The transformation of the neighborhood recalls the changes nearby on 4th Avenue and on the Williamsburg waterfront after both were rezoned in the aughts – but at a much more extreme scale. The rezoning covers 82 blocks – 20 more than the Hudson Yards rezoning – and allows towers as high as 30 stories along the canal, according to community group Voice of Gowanus.

Years in the making, the controversial rezoning of the area, home to small industry, artists and, in recent years, restaurants and recreation, incited strong local opposition and lawsuits. Alexiou said it is well known the area “is an environmental disaster” and developers would be tasked with undertaking mammoth site cleanup efforts under the supervision of the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation and with the help of the original polluters (for many sites that is National Grid).

“I do find it insane, you know, I don’t even think it’s hyperbole to say that, but that’s what’s been approved.”

While the developers who had scooped up properties in the area knew their obligations regarding lengthy brownfield cleanups, they weren’t prepared for the trifecta of Covid-19, high interest rates, and the expiration of the 421-a tax abatement program.

Some have managed to clean up sites, get financing, and push through the hurdles, but other owners, especially those who fell behind on construction and missed the 421-a tax break, left sites seemingly stalled. This all happened as the dialogue in the city around the need for new housing has hit fever pitch and the sunsetting of 421-a began to look like it would cause the rezoning to fail, leaving a blighted landscape and failing to deliver developer profits.

Responding to holdups caused by the sunsetting of 421-a, Governor Hochul created a workaround for 18 Gowanus and Carroll Gardens planned developments, allowing them to receive the same tax break they would have received through 421-a. Hochul said the plan will allow construction of 5,300 apartments in the rezoned area, of which approximately 1,400 will be rent stabilized and income restricted — what the city and state deems “affordable housing.”

Any development that takes advantage of the rezoning is required to include affordable units under the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program, whose options include 20 to 30 percent of units be rent stabilized and aimed at households earning 40 to 115 percent of the city’s Area Median Income.

During the rezoning process, the city council required that developers use the most affordable option provided through MIH, meaning 25 percent of units in a new development will be affordable, with 20 percent set aside for households earning an average of 40 percent AMI ($50,840 for a family of three) and 5 percent set aside for households earning an average of 60 percent AMI (currently $76,260 for a family of three).

If the program pans out as planned, around 1,060 apartments will be built and set aside for those earning an average of 40 percent AMI, with two-bedrooms renting at around $1,271 a month. Around 265 apartments would be for households earning an average of 60 percent AMI, which would see two-bedroom units at around $1,906 a month, at current levels.

The almost 4,000 apartments not covered by MIH will be free market and likely mostly rentals, judging by what is being constructed so far.

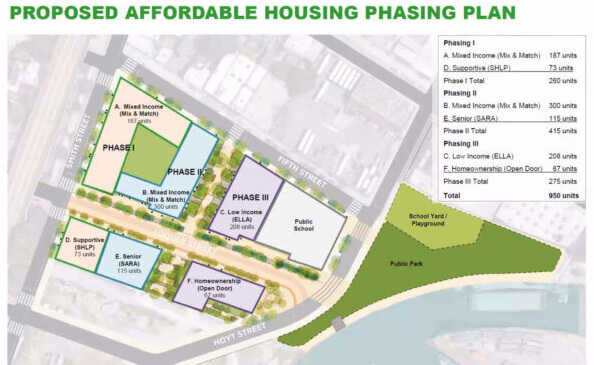

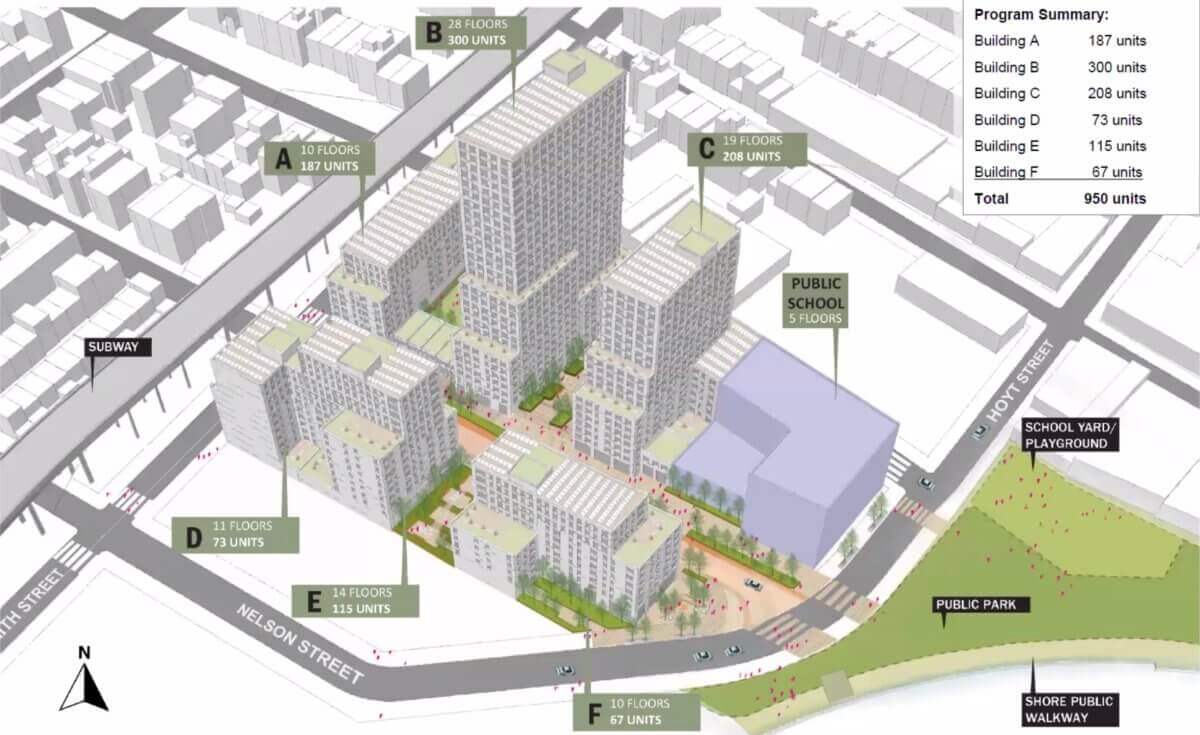

Much of the affordable housing being built in the rezoned area comes from Gowanus Green, which was in the works long before the rezoning was planned. Not on Hochul’s list, the six-building development will include 950 total homes, with 475 apartments set aside for households earning up to 50 percent of the Area Median Income and the others varying for those earning up to 120 percent, as well as including some affordable co-ops.

Eric McClure, chair of Community Board 6, said his and the board’s support of the rezoning was “driven by the really substantial need for housing in the community and across the city. We really thought that all things being equal, it was important to clear the way for the development of a substantial number of housing units in the neighborhood.”

He admits the changes over the past year “can be pretty startling,” but said viewed in the 4th Avenue or Downtown Brooklyn context, it isn’t too extreme. And the size of the developments, he said, serves the end goal of adding a few thousand more residents and allowing existing locals who are being squeezed by rent prices to stay in a “vibrant and active” area.

“It’s going to look different, but I think it’s going to also hopefully look nice and enticing and bring a new kind of dynamism to Gowanus that might not be there now.”

Walking among the green construction fences

Arriving in the neighborhood, it’s impossible to miss the 15- and 21-story towers at 420 Carroll Street on the eastern side of the canal near the Carroll Street Bridge, which has been closed since 2021 due to damage incurred during the canal cleanup. The topped-out towers are being developed by Domain Companies and designed by FXCollaborative, and will bring online 360 apartments. Presumably work was well under way when the 421-a tax break expired, so the developers aren’t in need of Hochul’s new deal (the site is not on Hochul’s list).

Just next door at 320 and 340 Nevins Street, and using Hochul’s workaround, is a giant development designed by Fogarty Finger and developed by Charney Companies and Tavros Capital that recently broke ground. Also a two-tower development, it will include 653 apartments.

On Union Street not far from Nevins, two huge developments surrounded in scaffolding and construction fences tower over the remaining low lying structures, including 20th century homes and factory buildings that house the Royal Palms Shuffleboard Club and Ample Hills Creamery.

To the south of Nevins is the topped out nine-story 499 President Street (it’s not included in Hochul’s list). Developed by Brodsky Organization and designed by SLCE Architect, it will comprise 350 apartments. To the north is 585 Union Street, an also topped out nine-story, 224-apartment complex designed by Fogarty Finger and again developed in a partnership between Charney Companies and Tavros Capital. The giant building, where windows are going in and the facade is being installed, faces Union and Sackett streets and 3rd Avenue.

According to Hochul, there are plans for a 60-unit development on the northwest corner of Sackett Street and 3rd Avenue, but no application for a new-building permit has been filed. Further down Sackett Street at No. 563, a developer wants to build a 12-story, 338-unit complex, although the permit application hasn’t been approved. Next door at 545 Sackett Street, on the corner of Nevins, remediation work is under way for a 10-story, 255-unit building designed by Handel Architects and owned by Peter Papamichael, according to permits.

A few blocks north at the corner of Nevins and Douglass streets, excavation is under way for another Fogarty Finger-designed, Charney Companies and Tavros Capital-developed 13-story, 261-unit building, which looks markedly similar to its sibling at 545 Sackett Street.

Unmissable as you walk up Nevins is the extremely long green fence, hub of workmen, soft spray of water, and construction noise signaling work on the two large sewer overflow tanks. The underground tanks will be covered with a “headhouse” building and public space.

Back down at the Union Street bridge, as you cross to the western side of the canal, is another eye-catchingly tall and glassy two-tower development at 267 Bond and 498 Sackett Street. The 21-story towers, designed by SLCE Architects and owned by Property Markets Group, will have 517 apartments once complete.

Across the road, in the lots bordered by Union, Bond, and Carroll streets, at least six new developments are planned, some rising as high as 23 stories. Already under way is 395 Carroll Street, a Sky Equity Group-owned site that takes up the entire block aside from 452 Union and 333 and 335 Bond Street. The developers have enlisted architect Hamish Whitefield to design a four-building complex — with heights ranging between six and 23 stories — that will include a total of 604 apartments.

Next door, on the site of the former Green Building at 452 Union Street, a 20-story, 158-unit building is planned. According to permit applications, Robert Doster owns the site and Magnusson Architecture is working on the design. Meanwhile, at 335 Bond Street, on the corner of Carroll, a nine-story, 70-unit building is under way with the foundations being laid. The development, designed by Studio V Architecture and owned by Robert Slinin, is not one on Hochul’s list.

Heading south to the 3rd Street bridge, a whole lot is happening there too. On the banks of the canal at 155 3rd Street, a 22-story, 301-unit development is planned. Designed by Dattner Architects and owned by Monadnock Development, permits for the building have been approved, but not issued. Next door at 129 3rd Street, Prospect Developers II are preparing the site for a 14-story, 130-unit building designed by Fogarty Finger. Again, new building permits have been approved but not issued.

Back across the banks of the canal, and directly across the road from Whole Foods, a Bjarke Ingles-designed 21-story, 450-unit building is planned to sit next to the landmarked Powerhouse Arts. The building permits for 175 3rd Street are still in process, but the architect has released renderings of the very creative plans for the build.

Heading south again, the biggest development planned for the rezoned area, and arguably the most significant, is Gowanus Green. Plans for the city-owned site at 5th and Smith streets call for a six-building, 100 percent affordable, 950-unit housing complex.

Gowanus Green is actually located in Carroll Gardens and had been in the works long before the Gowanus rezoning, under the name Public Place, and would have been built even without the rezoning. Rechristened and added to the scope of the rezoning late in the process, it was pivotal in getting the rezoning approved, with the community demanding a significant proportion of truly affordable housing. Fifth Avenue Committee, the Bluestone Organization, the Hudson Companies, and the Jonathan Rose Companies are behind the development. However, one major hiccup for the plans is that the low-to-moderate-income complex is slated for one of the area’s most polluted sites: the former Citizens Gas Works plant.

The plant, which sat on the six-acre site, was decommissioned in the 1960s before the city seized the lot in 1975 via condemnation, designating it “Public Place.” The gas company later became part of what is now National Grid, and the utility company started cleaning the soil in summer 2019 under the state’s brownfield program. In 2021, EPA’s Remedial Project Manager for the Gowanus Canal Superfund site Christos Tsiamis, who had been working on the canal cleanup since it was designated a Superfund site, set off a firestorm when he said at a community meeting he had concerns the level of remediation planned would not be sufficient to protect people’s safety, and that a higher level of decontamination would be necessary. In 2022, the EPA followed up on his assertions in a letter to the state.

Surrounded by a green construction fence, the site is currently covered in gravel but otherwise empty with neither workers nor equipment, and no work is happening there, recent visits showed.

The state’s Department of Environmental Conservation is overseeing what a DEC spokesperson called the “ongoing cleanup” at the Gowanus Green development site, and the agency is working with the state’s Department of Health and federal Environmental Protection Agency to coordinate actions. According to Department of Buildings records, excavation work and soil replacement has been done on the section of the site where the first buildings will rise (noted as 229 Luquer Street and 451 Smith Street).

A Hudson Companies spokesperson told Brownstoner the developers are aiming to have updated renderings released by mid-March and the first phase of design and funding for the first two buildings arranged with NYC’s Housing Preservation and Development this year. Given that timeline, and that remediation efforts are ongoing, it’s unlikely any construction will start this year.

Next door at 459 Smith Street, pile driving for three nine-, 21-, and 29-story towers was met with a legal action in 2022, in which locals alleged the work filled the air with the smell of coal tar, a toxic, carcinogenic sludge, and was extremely disruptive. While the suit was ultimately dismissed, work on the Hill West Architect-designed development hasn’t broken ground and the site is largely covered in gravel. DOB records show remediation work has been done on the property, although it is unclear if it is complete. The Real Deal reported earlier this month that the site has been sold to Canadian firm H&R REIT.

‘A cookie-cutter’ model

Gowanus local Martin Bisi, who has been in the neighborhood since the late ‘70s, said the vision for this new Gowanus kicked off with the Bridging Gowanus meetings in 2014 organized by then-Council Member Brad Lander to spur community support for a rezoning – which Bisi called “a bit of window dressing.”

“It is a cookie cutter, one-vision-fits-all for what the modern city is going to be,” Bisi said of the end result. He said while he understands the need for more housing, he thinks there is still a real need for industrial space, too, and said the rezoning had “eviscerated” a large amount of accessible commercial space.

Gowanus has long been home to many industrial businesses such as ironworks and auto repair shops that serve Brooklyn neighborhoods beyond the Gowanus borders. Bisi called the “gutting” of the industrial areas shortsighted on both a local and national level.

He also questioned the accessibility afforded to artists through the Community Benefits Agreement agreed as part of the rezoning, which provides around 150 artist studios in new developments for below market rate, starting at $12 per square foot a year.

To get a studio, artists have to apply and Bisi said an application would likely require a CV and favor an arts education, which he said many artists don’t have. “I’m a little appalled by the idea of having to apply for artists’ spaces,” he said. “That is problematic and depressing, really, for the future of the arts in New York City.”

Although the spaces will be owned by the developers, the applications will be reviewed and the studios will be allocated by nonprofit Arts Gowanus. “The process to equitably place artists in these affordable studios is still being finalized,” Arts Gowanus Executive Director Johnny Thornton told Brownstoner in an email, noting the application process has not yet started. “The application most definitely will not require or ‘favor’ an arts education.”

“Although there are a lot of legitimate concerns and criticisms about the Gowanus rezoning, we have done our best to make sure the arts community has a seat at the table in the ongoing civic planning,” he added.

Brad Vogel, a lawyer, poet, and preservationist active in the Gowanus community, lamented the loss of community gathering spaces such as Lavender Lake and Pig Beach, both closed because their buildings were being demolished. Other razed spaces include the popular event venue the Green Building, and the building of the iconic South Brooklyn Casket Co. Notably, the formerly crumbling and toxic Batcave, landmarked ahead of the rezoning along with a handful of other buildings, opened last year as Powerhouse Arts.

Vogel said if planning and development were being done “in a more conscientious way that respected the value that already existed in the neighborhood,” longstanding gathering spaces could still exist. Calling the rezoning and its effects “the clear cutting of Gowanus, in a way,” Vogel said the city had “forgotten or willfully disregarded” how humans relate to place and need anchors and some consistency, “at least in pockets.”

“There’s really a better way to do this that would be much more cognizant of what is of value to people who live in a neighborhood and that can give people who move into it value as well,” he said, adding while change is constant in Gowanus just as it is in the rest of the city, “the nature of the change and the scale and the scope of the change here just seems to be in hyperdrive compared to what’s come before.”

He said he hopes some of the neighborhood’s “eccentricities” and “unique cultural bent” survive the change and persist with new residents, but given the way development and planning is going he’s doubtful.

In a recent story in Biz Journal, Lee & Associates NYC broker Jeff Kessler said older retail spaces in Gowanus get around $60 or $70 per square foot, whereas new developments could go for between $100 and $150 per square foot.

Kessler said his team is currently looking for large spaces in the area for three athletic tenants, as well as spaces for other businesses. Southwest Brooklyn Industrial Development Corp. Executive Director Jesse Solomon was quoted as saying “you definitely don’t need more gyms,” and that Gowanus lacks and needs businesses focused on residential services like laundromats and supermarkets.

Addressing environmental concerns

Community group Voice of Gowanus, which counts Bisi and Vogel as members, has pivoted its focus from the rezoning to making sure environmental issues are addressed transparently. One member who has long been involved with advocating for the cleanup of the neighborhood is Linda LaViolette, who, like Bisi, moved to the area in the ‘70s, eventually opening a commissary for her catering company on Bond Street.

LaViolette said as things stand, the sewage system routinely pours pathogens into the toxic canal, which then overflows into the neighborhood’s streets. “That’s like something that you find in a third world country, to be honest with you.”

Sewage retention tanks the city is building to deal with overflow issues won’t be online for a decade, and LaViolette said there are concerns that the weather data used to establish the capacity for the tanks, and the entire rezoning, was from the 1980s and doesn’t factor in climate change.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency has sent multiple letters to the city and state expressing concerns about the impact of the rezoning and delayed tanks on the cleanup of the Gowanus Canal, a Superfund site.

At the same time, the neighborhood is still dealing with trying to remediate highly contaminated toxic land, the extent of which is still being uncovered. LaViolette said that after Gothamist released a story at the end of 2023 saying toxic fumes might have spread further than expected, there was a brief pause in development, but now “the construction between Union and Carroll streets has really gone on steroids.”

“My impression is they’re really trying to move as quickly as possible, so there’s less time to verify that everything is being cleared up,” she said. The state’s DEC signs off on cleanup, but if more extensive pollution were to be uncovered, potentially requirements could change.

Coal tar, TCE, and other chemicals detected in Gowanus are highly toxic carcinogens that can get into homes and other buildings through soil vapor intrusion (SVI). Voice of Gowanus has raised concerns about changing groundwater levels and their impact on the depth and concentration of the chemicals, with the increased flooding and other effects of climate change posing major questions for the cleanup. LaViolette said using the need for housing as an excuse to build on toxic land was “egregious.”

“The city needs to change, we’re not against change. I think we need affordable apartments. But is it right to put families and people on land that has not been fully remediated and is toxic? No, it’s not.”

The state’s Department of Environmental Conservation, which takes the lead on overseeing brownfield cleanups, has given out fines to developers in the canal area totaling $334,000, as of September 2023, for violations of state environmental protection laws and brownfield regulations, the agency said in a community advisory.

A DEC spokesperson said the agency is rigorous in its oversight of the environmental cleanup, and is continually monitoring all the cleanup activities at sites in the Gowanus Canal area to ensure compliance and protect public health and the environment. The Gowanus sites in the DEC remedial program have to investigate the full nature and extent of contaminants found on site, including in groundwater, soil, and soil vapor, and all cleanups developed are designed to address these contaminants and ensure public health and the environment are protected, the rep said.

Currently, DEC is overseeing the cleanup of 49 sites in the area, and is doing an expanded soil vapor intrusion investigation around the canal to assess neighboring off-site properties for potential soil vapor intrusion. The rep said the state will provide information to the community on the data developed and next steps based on the findings.

The spokesperson added community members should feel confident of the state’s “rigorous approach” to ensure their protection, adding state experts are available to discuss questions from the community with sites providing contact information for community members. The rep said DEC, DOH, and EPA use “the best available science to protect public health and the environment, both during the cleanup and after its completion.”

“Each site in the state brownfield or Superfund cleanup programs are adaptively and transparently managed using the site specific information driven by the extensive investigations required. All cleanup and construction activities on a site are designed to limit any exposures to contaminants and are carefully developed and monitored for effectiveness.”

The rep said DEC and DOH routinely meet with community members, including the Gowanus Community Advisory Group, to “discuss the state’s comprehensive efforts under way to ensure all cleanups are fully protective of public health and the environment.”

Meanwhile, the Gowanus Oversight Task Force was created to hold agencies to account on the 50 points of agreement made in the rezoning process. At the task force’s most recent quarterly public meetings, many of the questions asked were regarding the “comprehensive modernization” plan for NYCHA’s Gowanus and Wyckoff houses and how it would impact residents and address issues. Responses from NYCHA show the agency is yet to pick the design-build team for the project, after which residents will have to relocate for a period of time while the work is done on their units.

Brooklyn’s “Little Venice”?

How future development will pan out in Gowanus, beyond the dozens of projects currently planned or in the works with help from state tax incentives, remains murky. While a 421-a reboot has been pitched numerous times and Hochul is all for it, nothing has been locked in and, without it, developers say building big projects doesn’t pencil out. Meanwhile, some politicians have suggested lowering taxes on new developments and rental buildings.

Regardless of whether there is a lull in development once the current projects are complete, the sheer size and scope of what is already under way will see Gowanus dramatically altered compared to what it looked pre-rezoning. While other rezonings in the city (Williamsburg, Greenpoint, and Downtown Brooklyn, to name a few) have faced their own hurdles and have seen more of a gradual rollout, Gowanus is a stark contrast in how much is happening at once. Undoubtably there will be high demand for the affordable, rent-stabilized units that come online when the buildings open their housing lotteries. What remains to be seen is demand for the market-rate units.

If the 3,900 market-rate apartments predicted to be built through Hochul’s plan rent at rates similar to those available at 365 Bond Street, a one-bedroom will be going for more than $4,000 a month and two-bedrooms for more than $6,000 a month (a one-bedroom at 365 Bond is listed at $4,150 a month). It’s possible concessions will be used to lure tenants to an area that has been predicted to become Brooklyn’s own “Little Venice” (albeit with a canal filled with “black mayonnaise“).

Editor’s note: This article was updated with comment from Arts Gowanus on March 27, 2024.

Related Stories

- How Many Truly Affordable Units Could the Controversial Gowanus Rezoning Actually Create?

- Despite Building Boom, Housing in Brooklyn Is Not Getting More Affordable

- Locals Opposing Gowanus Rezoning Prepare for Potential Legal Fight

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

Comments