Construction Worker Collective Memorializes Those Lost on the Job, Offers Safety Training

Deaths and injuries for construction workers on the job have decreased in New York in recent years, and workers say that’s thanks to safety trainings they’ve organized themselves.

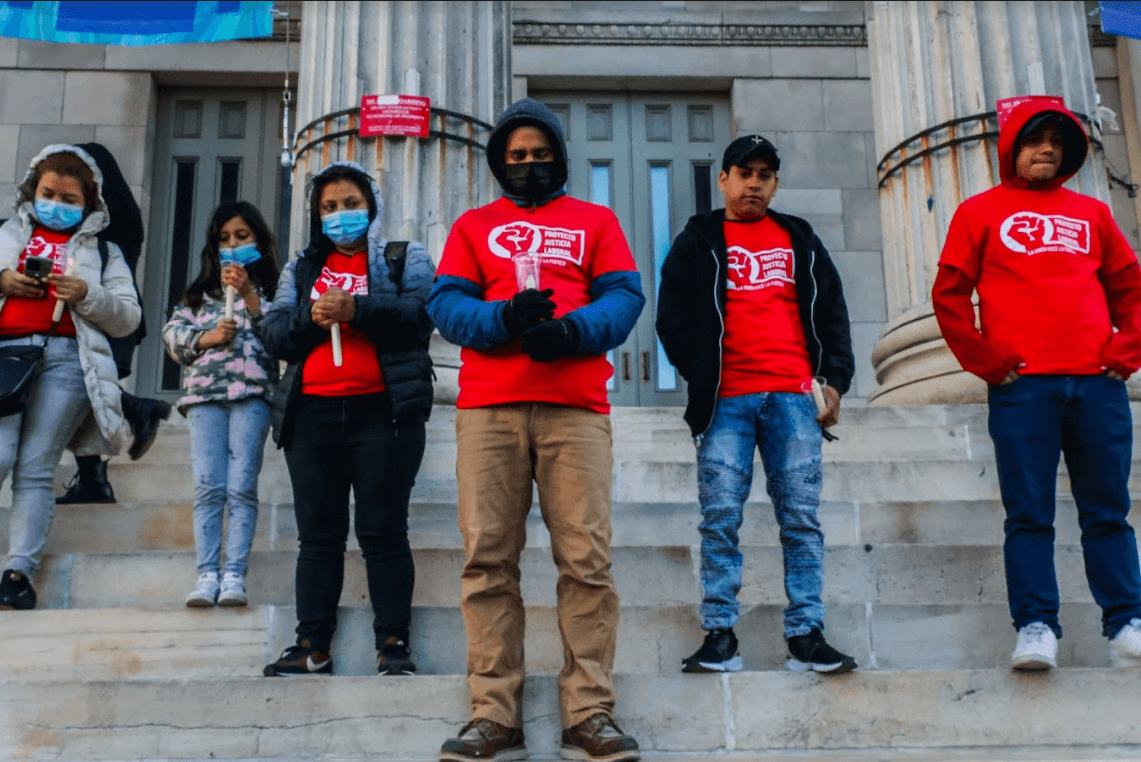

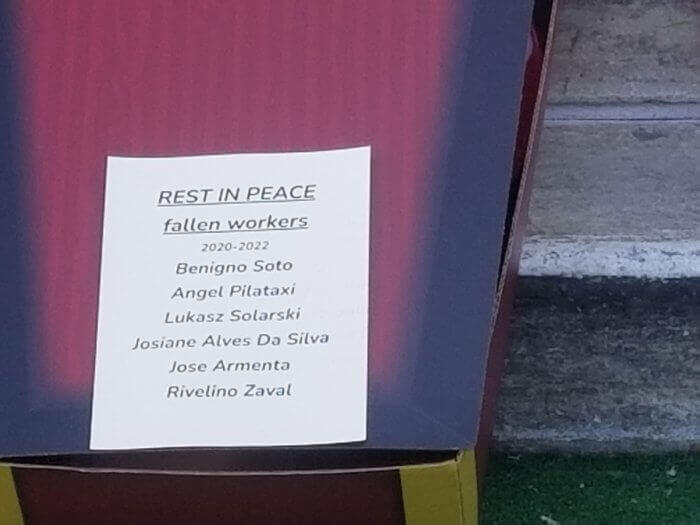

WJP members, pols, and allies gather around a mock coffin with the names of construction workers who died on the job this past year on April 28, 2022. Photo by Adrian Childress

Deaths and injuries for construction workers on the job have been on a significant downward trend in New York in recent years, and hard hats say that’s thanks to trainings they’ve organized themselves on site safety, labor rights, and how to securely blow the whistle on violations.

As Brooklyn Paper previously reported, injuries on worksites across the five boroughs have fallen from 759 in 2018 to 505 in 2021, per the Department of Buildings’ 2021 Construction Safety Report. Deaths similarly fell, from 13 in 2018 to nine in 2021. The downward trend coincides with regulations passed in 2017 as Local Law 196, which requires workers to complete 40 hours of safety training devised by the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) before being certified to work on construction sites.

Those trainings provide vital safety information on all manner of topics, like working with ladders, electric work, and excavation, in a 30-hour class, and education on recognizing hazards, knowing your rights, and reporting violations in an additional 10-hour session. But they’re expensive: the complete required package provided direct from OSHA currently costs $208, which is a discount price from the typical $298.

Enter the Workers Justice Project, a collective that organizes and lobbies for the rights of low-wage, usually immigrant workers. The group has become well known in the past several years for organizing delivery cyclists as Los Deliveristas Unidos, and successfully pushing for major labor reforms in the food courier industry.

The group also has a construction workers division which puts on its own OSHA trainings, an unlimited number of which are included in a $50-per-year WJP membership. The group says it has trained 4,000 workers in the past two years.

WJP conducts its trainings in Spanish, crucial in an industry where 56 percent of employees speak a language other than English in the home (the vast majority of those speaking Spanish, according to a report from the New York Building Congress). Many are undocumented immigrants who may feel hesitant challenging their boss or contacting federal authorities, fearing detention and deportation, so the WJP guides workers, in their own language, step-by-step through their legal rights in the workplace, how and when to report violations (the group even conducts roleplays), and who to reach out to in such a case, all imbued with the knowledge that their legal status will not factor into their complaints.

Although deaths and injuries have declined in recent years, in the years between passage of Local Law 196 and the start of the pandemic, violations grew substantially, peaking at over 95,000 in 2019 according to DOB’s 2019-20 construction safety report. That’s not because the sites were less safe, WJP says, but because workers now are being trained to be more diligent in spotting and reporting violations.

“The workers are the ones calling OSHA or DOB to report the unsafe working conditions,” said Yadira Sanchez, a co-founder of WJP and the leader of its construction division, in an interview with Brooklyn Paper. “Now they know that they have rights, they can complain, now they know that they can say no because the work environment is unsafe.”

Most construction work halted after the onset of the pandemic in 2020, and because of that, violations fell sharply to about 68,000 that year. The following year, with the industry back in swing though still recovering, DOB logged about 78,000 violations, with Brooklyn topping the five boroughs at 26,255. That’s well below 2019 levels, which WJP attributes to the long-term impact of the robust worker trainings and to DOB inspections where, if sites are found to employ non-certified workers, they could be slapped with thousands of dollars in fines.

With workers thus more in command of their rights and safety, and the threat of fines looming for hiring unlicensed employees, WJP says bosses are starting to get the message that corner-cutting is more difficult than it once was.

“The pressure comes from the DOB, OSHA, and the knowledge of the workers,” Sanchez said. “If the workers know their rights, they’re gonna challenge the supervisors. But in the past they couldn’t do that, they didn’t know how to, they didn’t know their rights. So it’s more common.”

“It’s not only about talking to the contractor, but also the worker knowing and recognizing what is a risk, and how to diminish or remove or erase or fix the dangerous situation,” Sanchez continued.

Carlo Scissura, president of the New York Building Congress, a powerful construction industry trade group, says that the building trade prioritizes worker safety over all else, and said that the decline in tragedies in recent years has been the result of industry-wide collaboration to make the job safer.

“Safety is and always will be priority one on any worksite. The building Industry has always made safety top of the list on every single job, period,” Scissura said in a statement to Brooklyn Paper. “The truth is that the steady decline in tragic accidents the past few years is the result of an industry-wide cooperative effort that involves workers, builders, subcontractors, and even elected officials. To keep our workers safe, legislation, regulation, and licensing must always keep up with the times and technology. Everything that can be done, will — not should, will — be done as expeditiously as possible, and our members will always lead the way on ensuring best practices.”

Despite the improvements, the very nature of construction work means it remains a dangerous industry for employees. Nine construction workers died on the job last year, including three in Brooklyn. WJP held a memorial for them last week, calling for increased accountability to ensure developers prioritize the safety of their workers.

“It’s incredibly sad every time we have to gather under these circumstances where it’s a vigil, because they are 100 percent preventable,” said City Councilmember Jennifer Gutierrez, who reps Williamsburg, Bushwick, and Ridgewood, Queens, at the memorial on the steps of Brooklyn Borough Hall. “I can’t tell you how shaken up I am every time I hear about it. But I continue to be shaken up because we are not doing enough. Every time we accept a fatality on the worksite, we are failing you, we are failing the city.”

Construction worker and WJP member Nelson Llumitasig has lived in Bedford-Stuyvesant for the past three months since immigrating to New York from his native Ecuador, in search of stable employment, which he found in construction. He connected with WJP through a friend, got the necessary training for his certificate, and is now making a living in his new home.

But Llumitasig continues to organize for better working conditions for himself and others in the industry, finding that bosses are still wont to cut corners. He was horrified to learn that helmets and vests are not provided and must be purchased by the employee, which put him out about $32 total — and he is scared for his safety, especially when working from towering heights.

“I’m a bit worried when they send me to very high heights and bring up materials like paint, without the proper [personal protective equipment],” Llumitasig told Brooklyn Paper in Spanish.

The ongoing lack of assurance that construction workers can expect to go to work and return home unscathed means WJP will continue to organize, provide their trainings, and memorialize fallen colleagues. In February, construction worker Angel Pilataxi fell 10 stories to his death from the roof of 124 Columbia Terrace. The former Jehovah’s Witnesses building was sold back in 2017 to billionaire Vince Viola — owner of the National Hockey League’s Florida Panthers — who plans to convert the property into condos.

Viola is worth $3.9 billion according to Forbes, and the sale of his Brooklyn Heights townhouse last year netted him a cool $25.5 million, the highest sum ever attained for a home in Kings County. Attendees of the memorial questioned why someone so wealthy couldn’t invest in ensuring the safety of his construction site.

“This happened at a luxury housing development,” said City Council Member Lincoln Restler, whose district includes Greenpoint, Williamsburg, Downtown Brooklyn, Boerum Hill and Brooklyn Heights. “A building that sold for over $100 million is owned by a guy who has a professional sports team in his portfolio, an extraordinarily wealthy individual. But he didn’t invest the resources to provide the necessary training and ensure the safety of the workers on site. It’s unconscionable. It should never have happened.”

Editor’s note: A version of this story originally ran in Brooklyn Paper. Click here to see the original story.

Related Stories

- Brooklyn Racked Up the Most Construction Violations in NYC in 2021, Says DOB Report

- Worker Plummets to Death at Former Witnesses Dorm Construction Site in Brooklyn Heights

- City Council OKs Controversial Atlantic Avenue Towers After Developer Ups Affordable Units

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment