The Battle of Gettysburg in the Round: Brooklyn's Lost Cyclorama

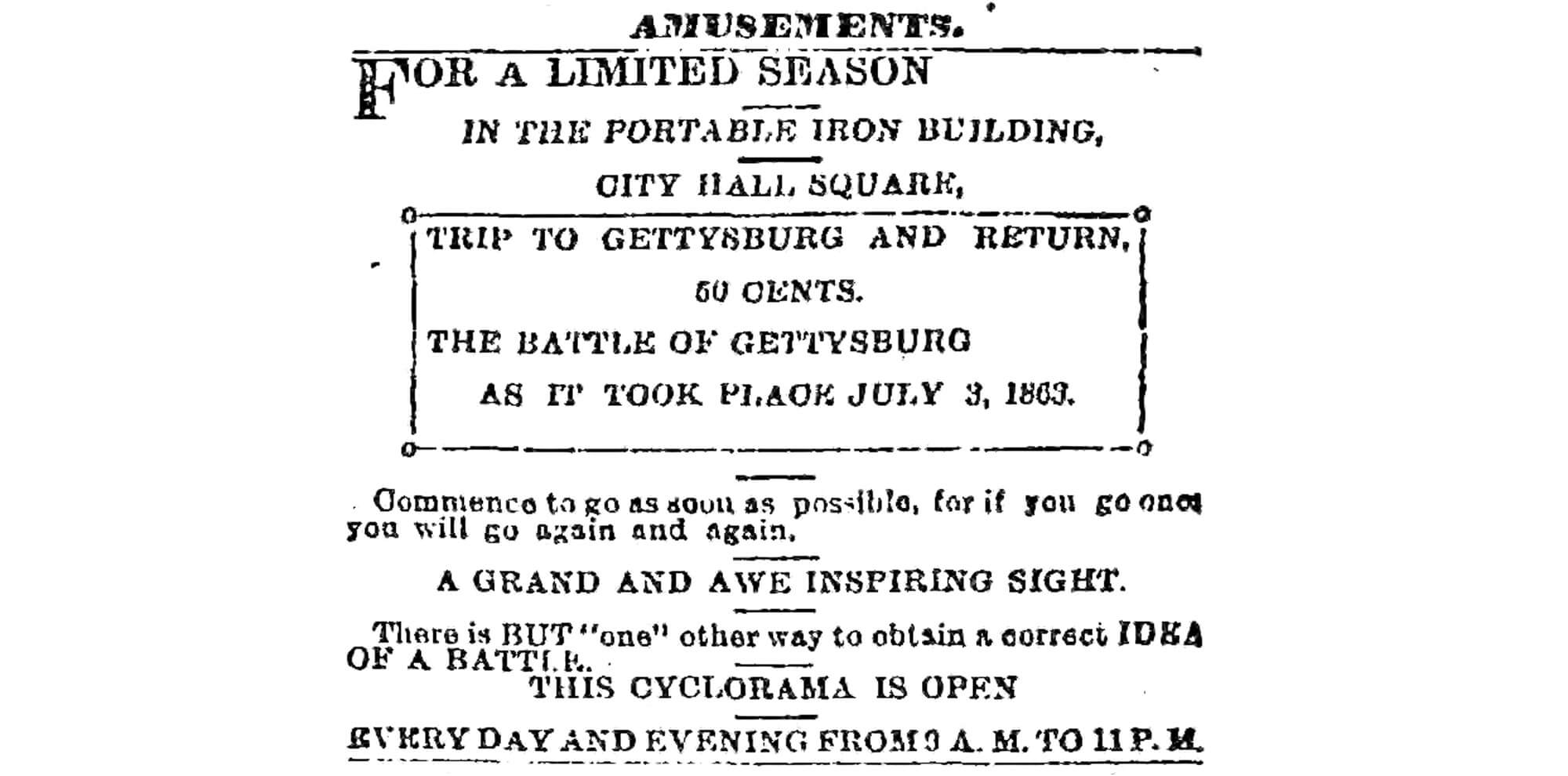

A precursor to the cinema, a major exhibition depicting the pivotal 1863 Battle of Gettysburg stood near Brooklyn City Hall in Downtown Brooklyn for years, where thousands paid 50 cents each to view it.

Editor’s note: This story is an update of one that ran in 2015. Read the original here.

The Battle of Gettysburg, in 1863, was one of the pivotal turning moments in American history. Those who took part in the battle, on both sides, were affected by it for life. So too were the families of all who died, or came home maimed and tortured by the experience. The Pennsylvania battleground became a powerful symbol of the horrors of war, especially civil war, where the enemy is not a foreign nation or ideology, but one’s own countrymen. The battle had moved a president to its fields to honor those who fought, and those who gave their all. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is one of the few speeches schoolchildren still memorize today.

Twenty-some years after the end of the war, its effects were still on the national psyche. In northern cities like Brooklyn, the generals and officers in the war came back and became politicians, city officials, bankers, heads of railroads and utilities, lawyers and businessmen. The veterans of the war were everywhere, in every walk of life. The G.A.R, the Grand Army of the Republic, the Union veteran’s organization, was a popular place for men to meet and be with the only people who really understood them.

The public was fascinated by the war in general, and the Battle of Gettysburg, in particular. There were lectures given by former soldiers, as well as military strategists. They talked about troop movement, charges, the generals and their mistakes or brilliant moves and, always, the wounded and dead. One man was so fascinated by the war that he decided to illustrate it in such a way that it could be understood by a wider audience of people. In this day before motion pictures, he decided that the best way to show this battle of battles was to paint some of the major moments and paint them large.

Paul Dominique Philippoteaux was a French artist, born in Paris in 1846. His father was a painter, as well, and he studied in his father’s studio, at the famed L’École des Beaux-Arts and in the studios of several other Paris artists. He and his father became interested in painting cycloramas. They are large panoramic cylindrical paintings, depicting epic events like famous battles or, in the case of religious cycloramas, events like creation or the crucifixion.

While still in Paris, Philippoteaux and his father painted The Defense of Fort d’Issy in 1871, which was a bit hit, and went on to depict several other epic 19th century European battles. They were also very successfully exhibited. In 1879, a group of Chicago investors invited him to immortalize the Battle of Gettysburg. He spent several months in Gettysburg in 1882 making sketches and drawings, and taking photographs of the fields and land involved in the various parts of the battle.

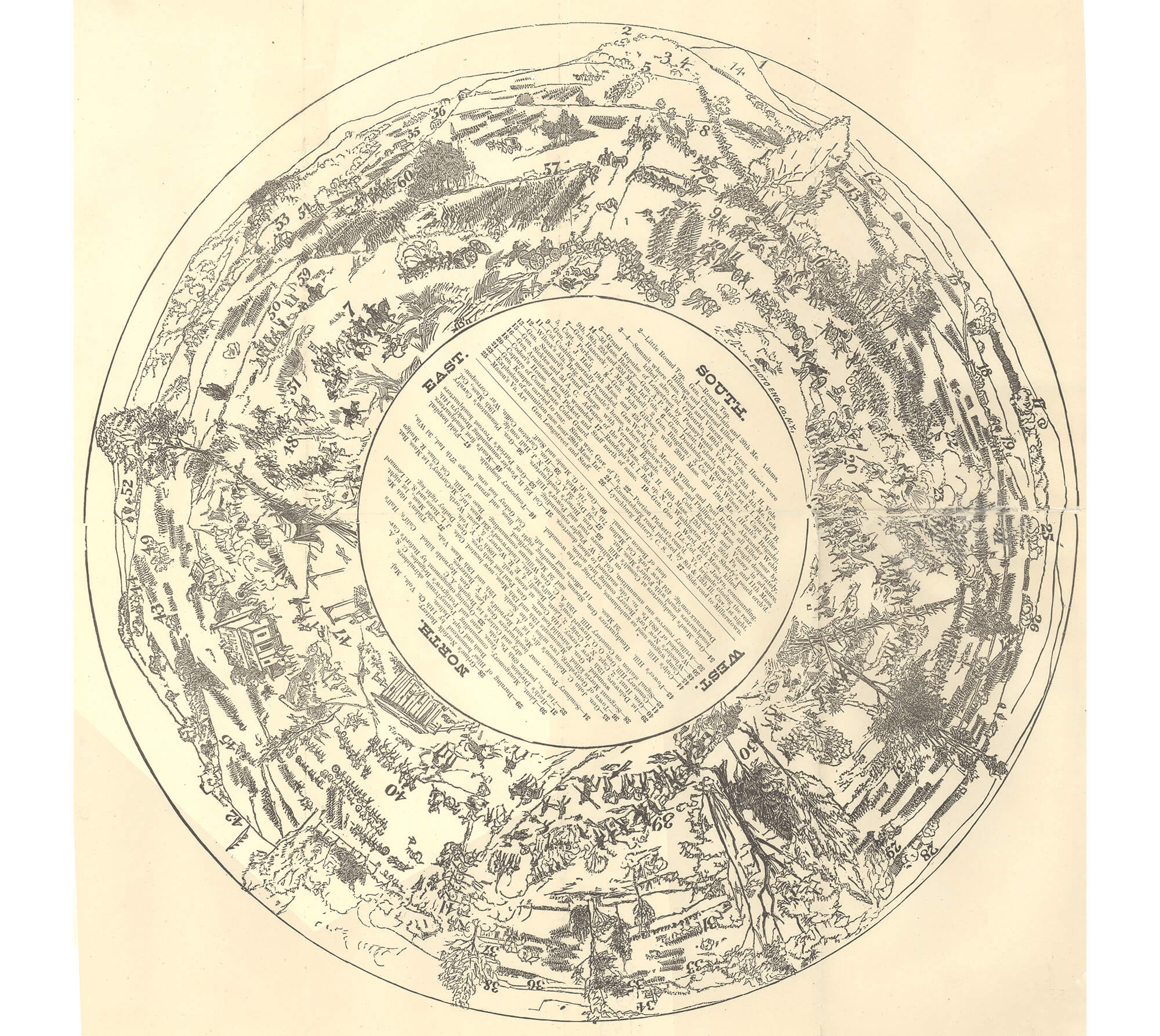

He was meticulous, dividing his chosen area into sections and having photographer William H. Tipton photograph every inch. Later, the photographs were all pieced together, forming the basis of the background for the scenes and dictating which parts of the battle he would show. Philippoteaux also did his research, reading everything possible on the battle and interviewing veterans, including Union generals who were on the scene, getting their perspective on the site, the battle and its aftermath.

After all of the research and prep work was done, the artist, his father, and a band of four other assistants began sketching the scenes in ink, and then painting. The work took two years to complete, during which time the elder Philippoteaux died. His son continued, and when they were finished, the completed canvas was nearly 100 yards long and weighed six tons.

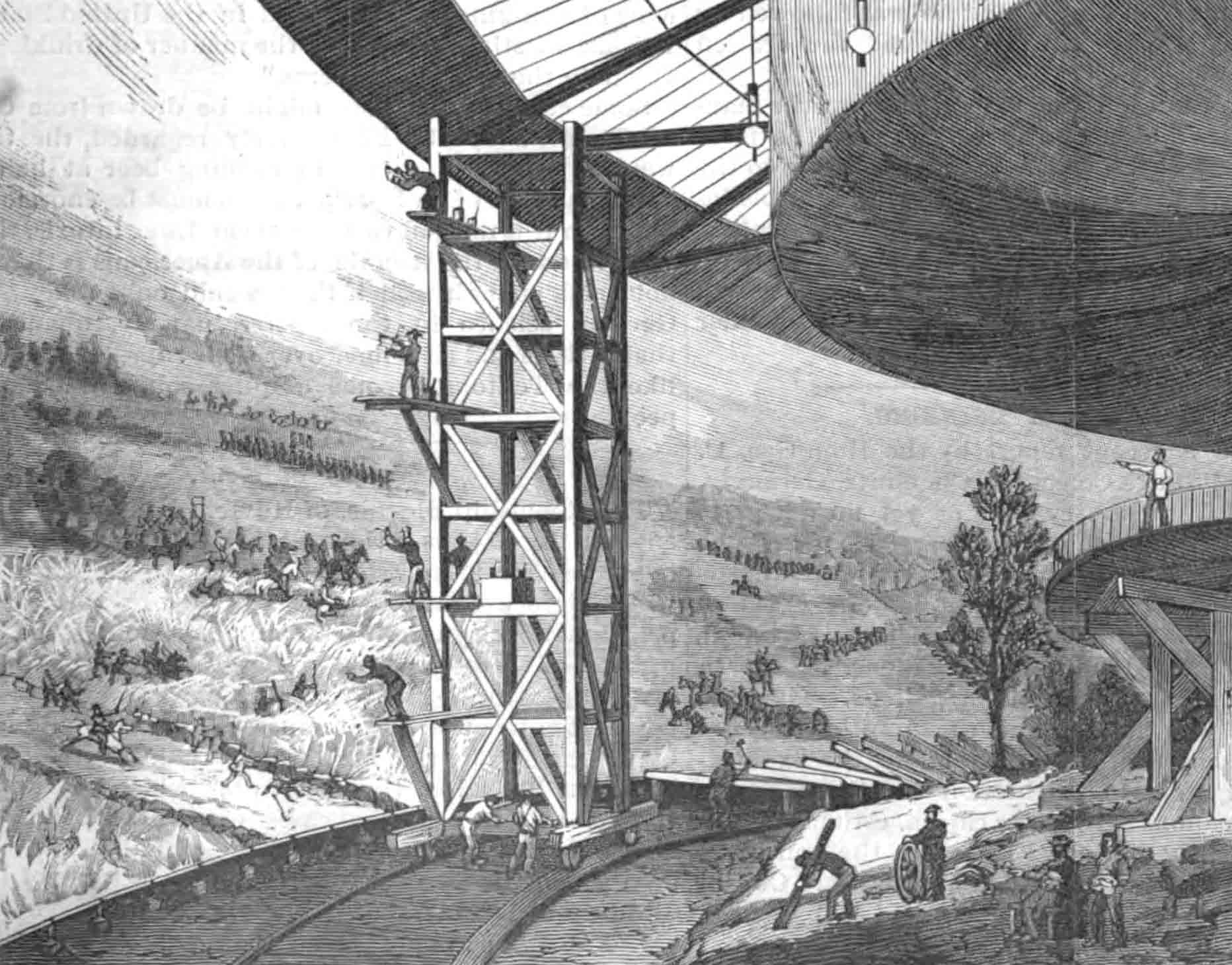

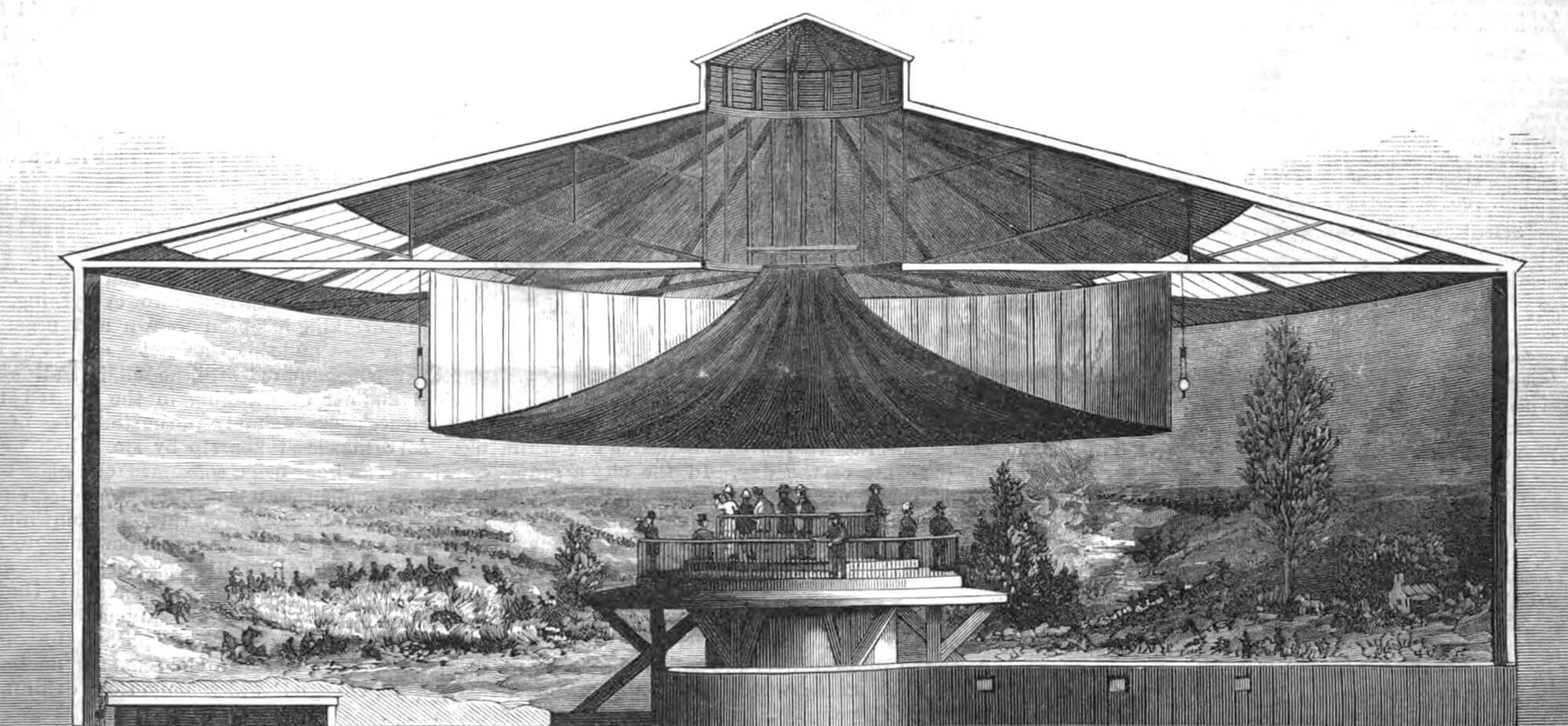

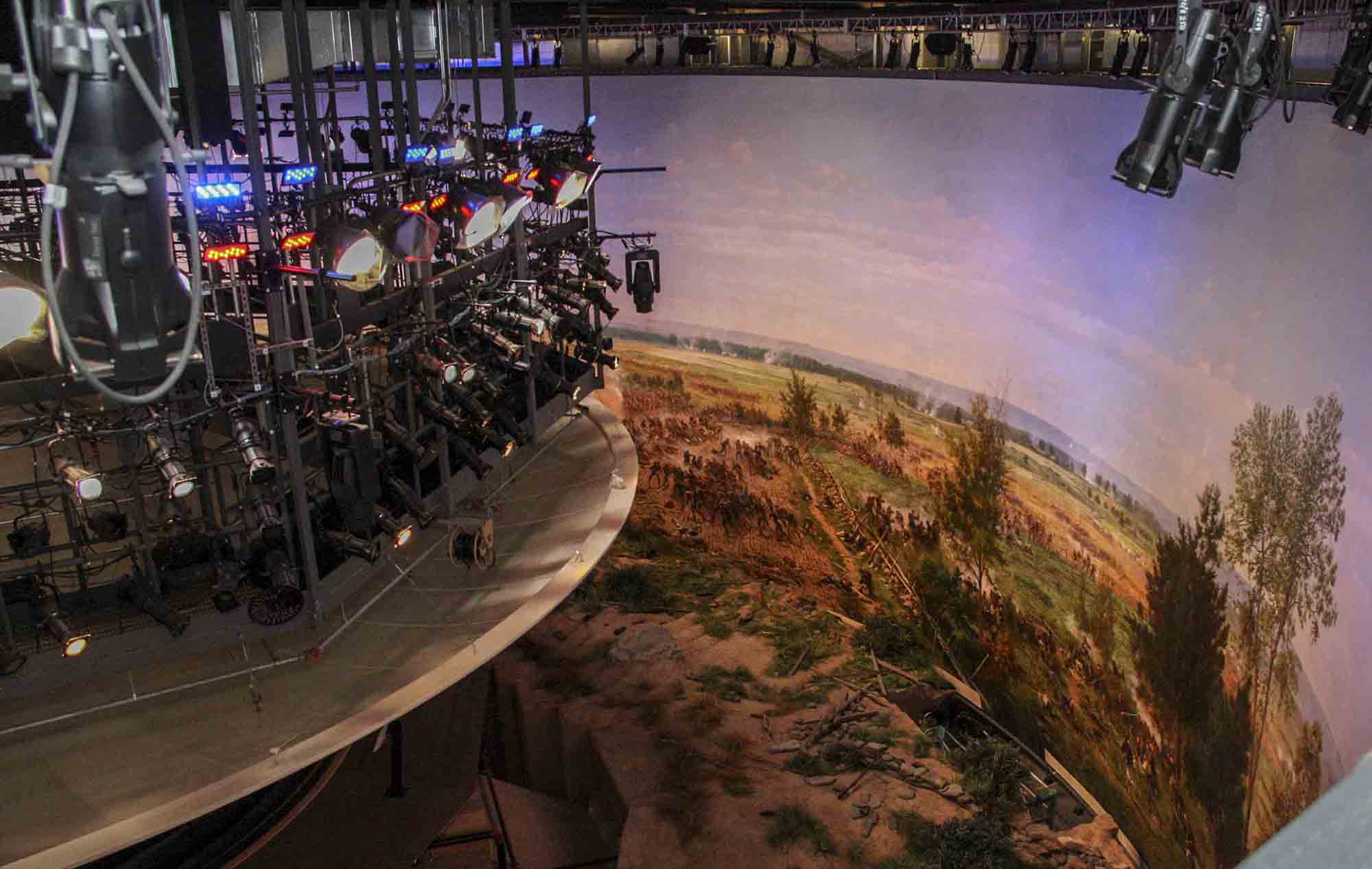

When the entire exhibit was put together, it also included artifacts and sculptures, including stone walls,trees, fences, and mannequins dressed and placed as dead soldiers. The closest thing we have today would be an IMAX film, with details so lifelike and three dimensional, one would expect to smell the cordite and blood.

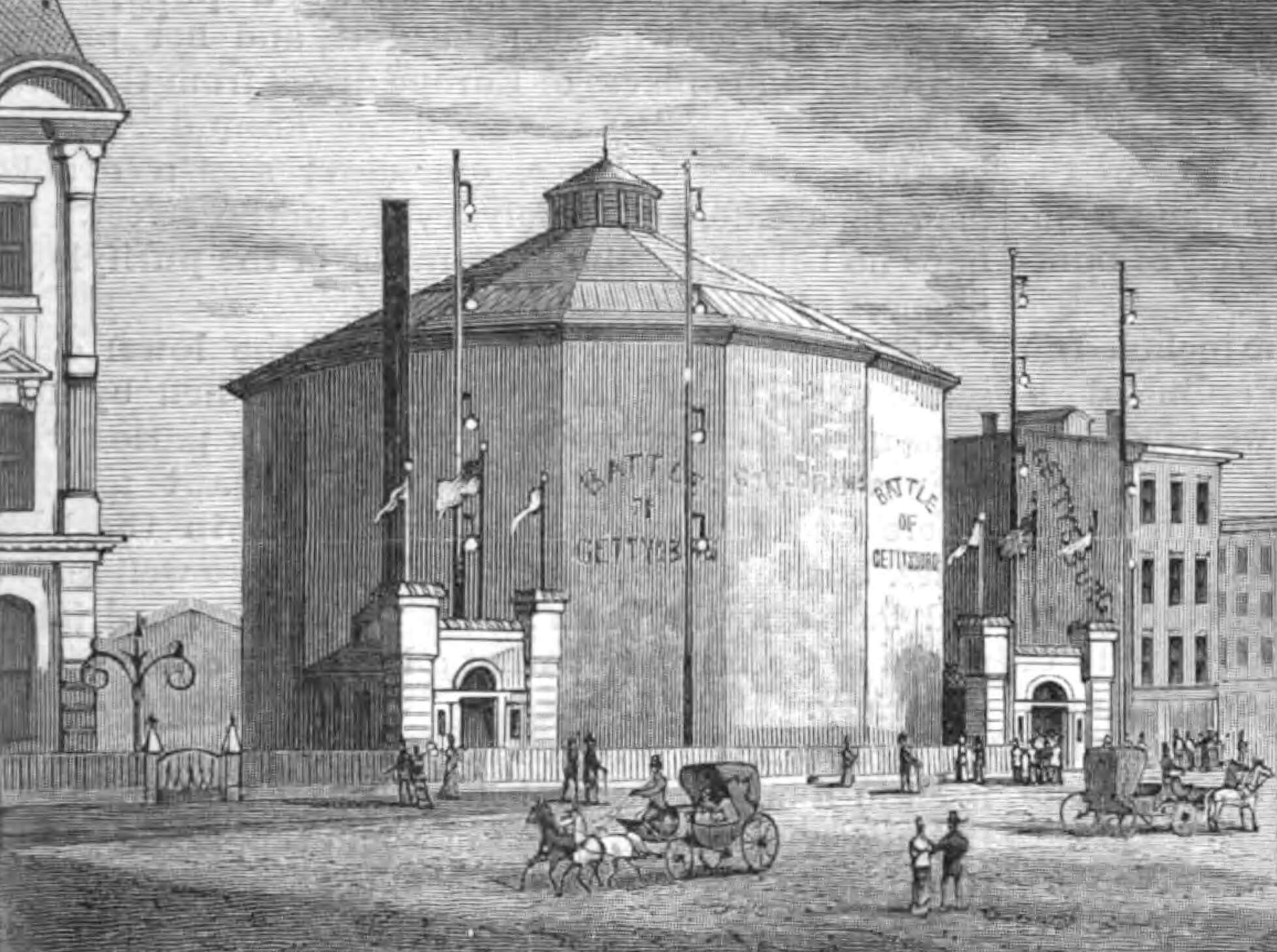

The investors in Chicago built a special round building for the cyclorama. It looked very much like a gasholder building, a large cylindrical tank-shaped building with a high roof. The canvas, which was 42 feet high, was stretched around the outer wall, and the objects and trees, and props were arranged in front of it, moving into the room like a 3-D movie. The audience would walk down a passageway and stand on a platform in the center of the room.

The canvas was stretched in a hyperbolic shape, curved to create depth. Skylights were often cut into the roof where the clouds were painted, allowing sunlight to pass through and creating a low-cost special effect that gave the illusion of being there. This was highlighted by the extra scenery and props. Curtains and draperies were also hung strategically and the room was darkened except for where light was directed, which disoriented the viewer and added to the illusion of being transported to the actual place and time.

When the cyclorama debuted in Chicago on October 22, 1883, it was to critical acclaim. One of the generals, John Gibbon, who had actually repelled Pickett’s Charge, one of the main engagements depicted in the piece, said it was very accurate, and he gave it a good review. It was a huge success.

The newspapers reported that veterans of the battle broke down and wept at the accuracy and the realistic depictions. The investors immediately ordered three more canvases. The show was going to go on the road. Philippoteaux and his crew went back to work, moving to New York to reproduce the canvas three more times. They went to cyclorama exhibits in Boston, Philadelphia and Brooklyn.

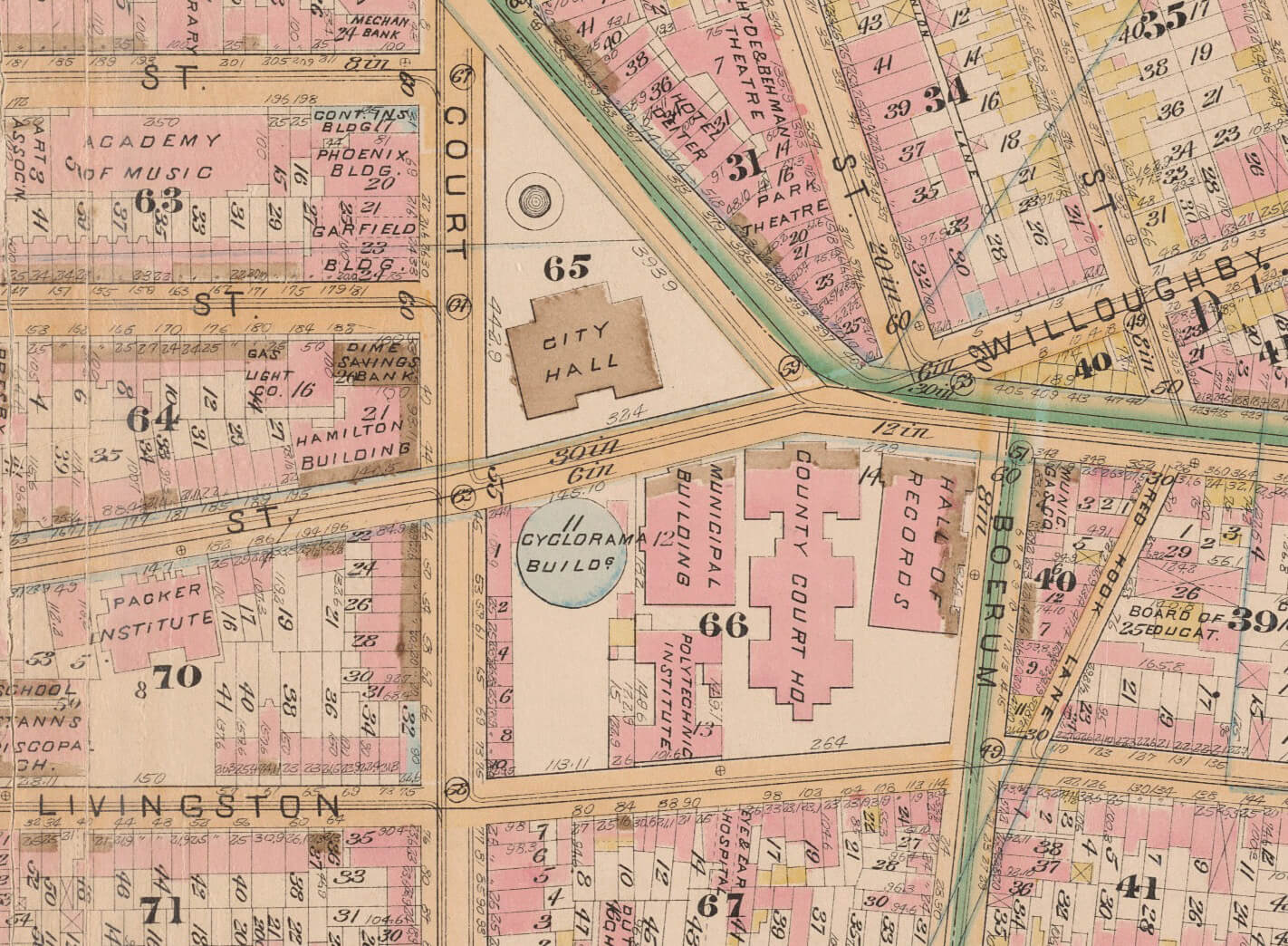

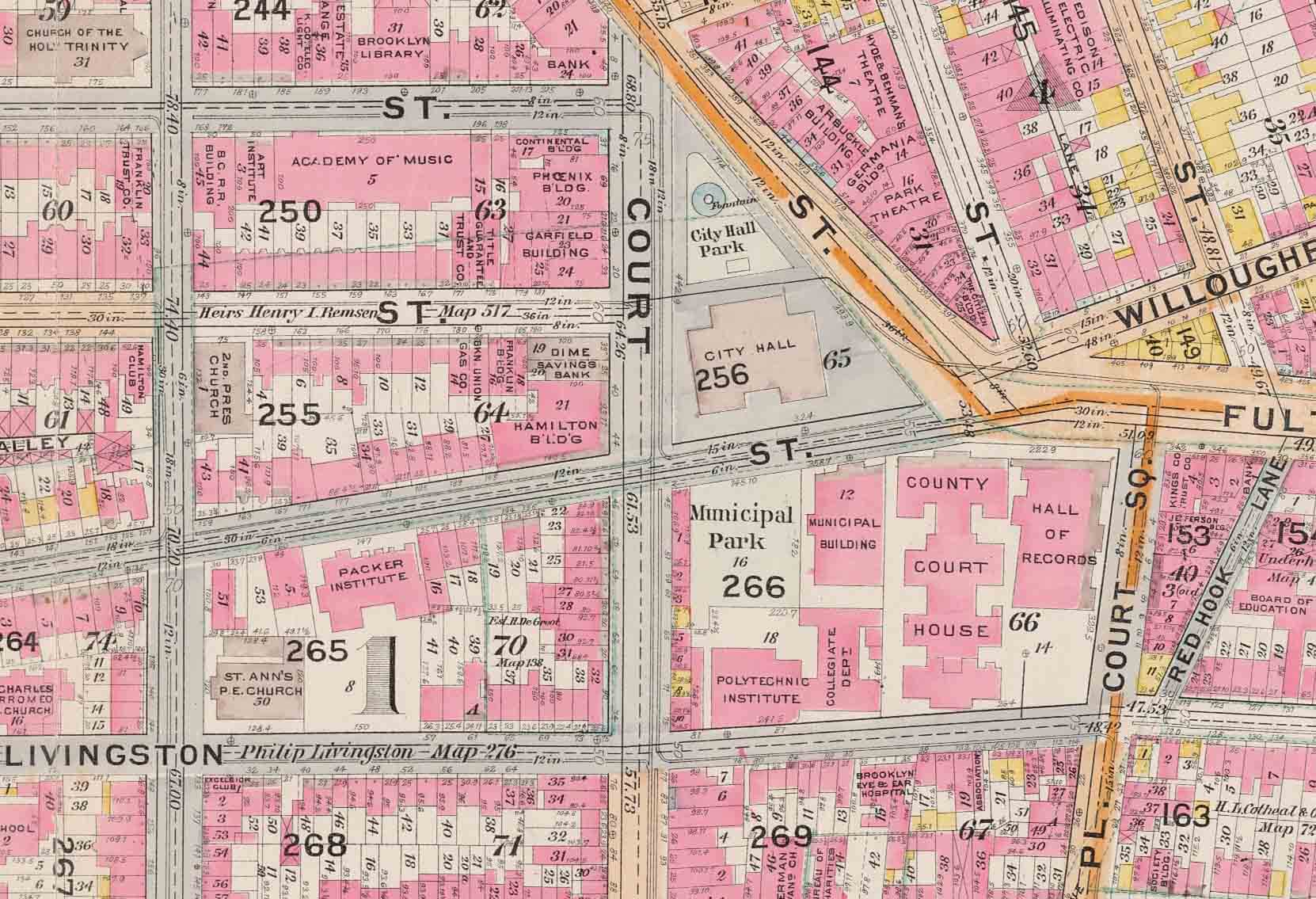

The First Reformed Church, known locally as the Old Dutch Church, had been on the corner of Court and Joralemon Streets since 1804. The city’s Municipal Building had been built right next door, and both were across the street from City Hall. The church wanted to sell the building and move, but hadn’t been able to find a buyer. In March of 1886, Chicago entrepreneur Charles L. Willoughby announced that he was buying the lot. He paid $250,000 for this prime site, a fortune at the time.

He told a Brooklyn Eagle reporter, “The purchase was made because the property is, I think, one of the finest pieces in Brooklyn and well suited for my purposes. I will commence in May to tear down, and immediately build a large fireproof building, in which the cyclorama of the Battle of Gettysburg will be placed on exhibition. The building will be octagonal, 400 feet in circumference and 100 feet high. The cyclorama is now being painted in New York by Paul Philippoteaux, the well-known French artist.”

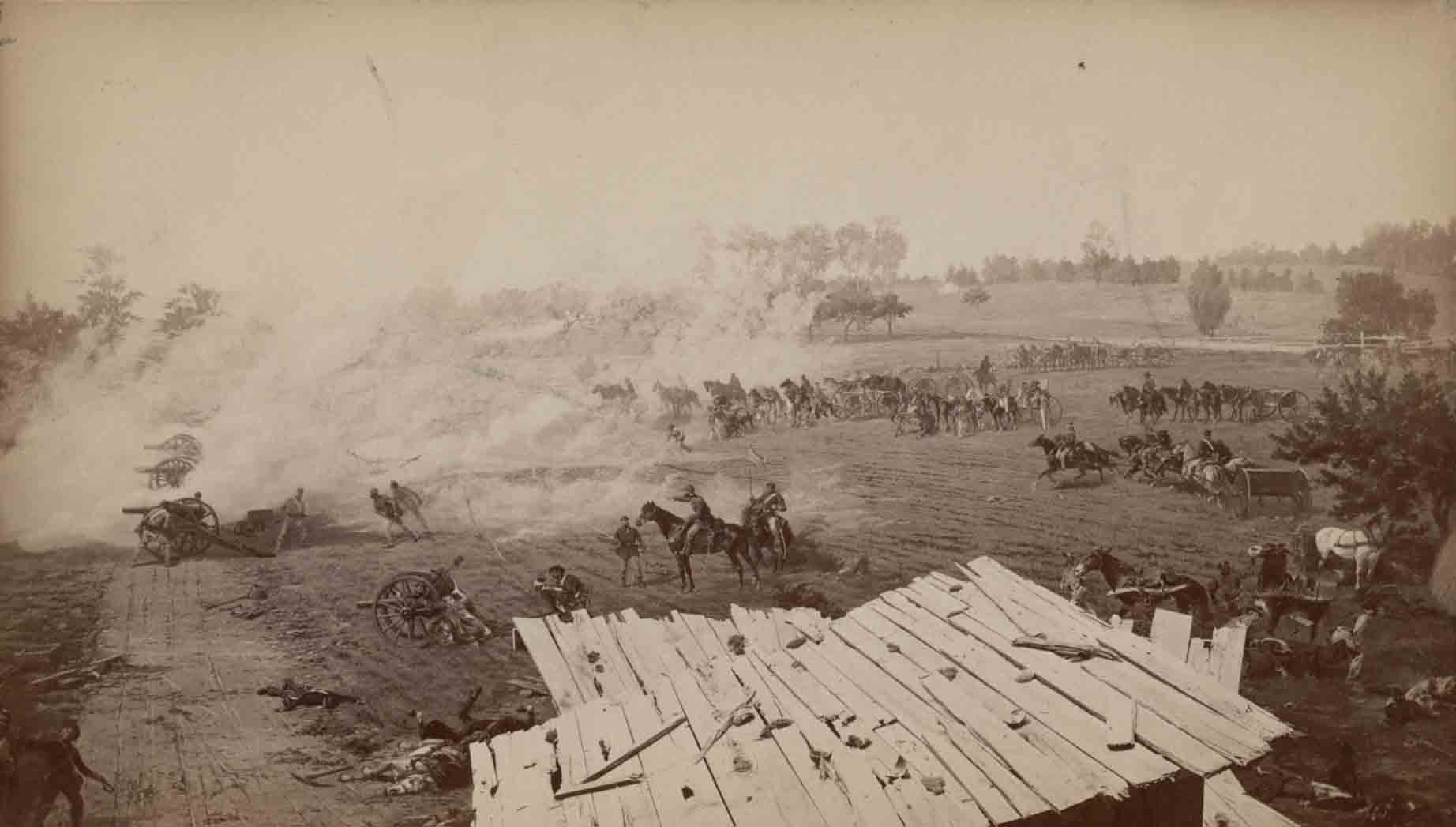

The Brooklyn Gettysburg canvas was the last of the four to be painted. By this time, Philippoteaux and his assistants had everything down pat, having worked out any problems in the piece over the course of creating three others. He considered this one to be the finest of the lot. A writer for the Eagle had a look before the opening, and reported that “the drawing is firm, the color good, the light brilliant, the action spirited, the forms well posed and the sense of energetic movement is conveyed in every quarter. In such things as the attitude of galloping horses, the flash of guns and the roll of smoke over the ground close observation and ready wit have been displayed, and in uniforms, accoutrements, harnesses, flags and so on, the artist has painted from models as closely as in his figures.”

The building opened with great fanfare in October of 1886. Admission was 50 cents for adults and 25 cent for children. The building was open from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m., allowing people to come in all day. Since not all that many could crowd onto the platform at one time and people lingered for hours looking at everything, the lines were long in the beginning, and the building stayed busy for months. It was a huge financial success.

In March of 1887, during a windstorm, parts of a chimney from the Municipal Building next door fell onto the roof of the cyclorama and burst through the building. The bricks landed on one of the dead soldier dummies on the floor of the building. Fortunately, the canvas was not damaged and repairs were made to the exhibit and the roof.

The exhibit was never meant to last forever, and after a year, the audience began to wane. The owners decided to take the exhibit on the road. The Gettysburg Cyclorama closed in August of 1887, and was taken to a new cyclorama built to hold it in Manhattan. The popularity of this particular cyclorama had caused similar exhibits to be built all over, including at Brighton Beach, each with different themes and scenes. The Gettysburg battle was copied, but not as well, many times, and although there were great cyclorama paintings after this, none ever matched the quality and majesty of Philippoteaux’s canvases.

With the cyclorama gone, there was no need for the large round building in the middle of the civic square. The building was torn down, and for quite a while the lot remained empty, until George Murphy, a Department of Public Works employee, established a park for only $650. It was named after him, although the name was later changed to Municipal Park. The park was nestled between the Municipal Building, the Polytechnic Institute and a row of houses facing Court Street.

After a couple of years, the park became known as a hangout for panhandlers, homeless, thieves and pickpockets. By 1906 it was a storage yard for contractors building the nearby subway stops. In 1915, the Municipal Building was torn down, in anticipation of finally building a new one, but both lots remained empty for years.

Locals petitioned the city to turn it into a parking lot, but the city never did. During World War I, the lots were used as an exercise and drilling field for student soldiers training for war. Parts of Polytechnic were turned into barracks for these young soldiers. Finally, in 1925, ground was broken for the new Municipal Building, the one we have today, designed by McKenzie, Voorhees and Gmelin 10 years before.

What happened to Philippoteaux’s Gettysburg cyclorama? Of the four originals, the Chicago one went on tour and was eventually exhibited at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. It now belongs to a group of private investors in North Carolina. The Philadelphia painting was destroyed in a warehouse fire. The Boston cyclorama, after being divided into pieces, hung in a department store, and was treated horribly over the years. The pieces were tracked down and purchased by the Gettysburg Museum. After an extensive and expensive restoration, it is now on display in its own cyclorama building on the battlefield site.

The Brooklyn painting is also gone. After its Manhattan run, it toured and was eventually cut up into pieces and distributed to Civil War Veterans’ groups and individual veterans. Some of the pieces are on display at the exhibit at Gettysburg. Cycloramas died out when motion pictures were invented. The drum-shaped buildings would soon be replaced by theaters, some of them as fanciful as anything ever known and just as awe inspiring and wondrous. Paul Philippoteaux died in Paris in 1923. He may not have known it, but he inspired the visual and digital artists who create the wonderful and detailed worlds of imagination we enjoy in our cinema today.

Related Stories

- Walkabout: New York’s Infamous Draft Riots

- Past and Present: General Slocum’s Statue

- Walkabout: Kidnapping General Grant

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment