A “Mixed-Race” Wedding in 1907 Bed Stuy Attracts Unwanted Attention

Brooklyn, one building at a time. Behind the most ordinary brownstone facades lies the real history of Brooklyn, where prejudice and ignorance against anyone not of Northern European descent was common. In 1907, racial prejudice led to snooping on a wedding that took place in this Bed Stuy house. Name: Row houses Address: 171-177 Putnam…

Brooklyn, one building at a time.

Behind the most ordinary brownstone facades lies the real history of Brooklyn, where prejudice and ignorance against anyone not of Northern European descent was common. In 1907, racial prejudice led to snooping on a wedding that took place in this Bed Stuy house.

Name: Row houses

Address: 171-177 Putnam Avenue

Cross Streets: Franklin and Bedford avenues

Neighborhood: Bedford Stuyvesant

Year Built: Late 1870s, before 1880

Architectural Style: Transitional Italianate-Neo-Grec

Architect: Unknown

Landmarked: No

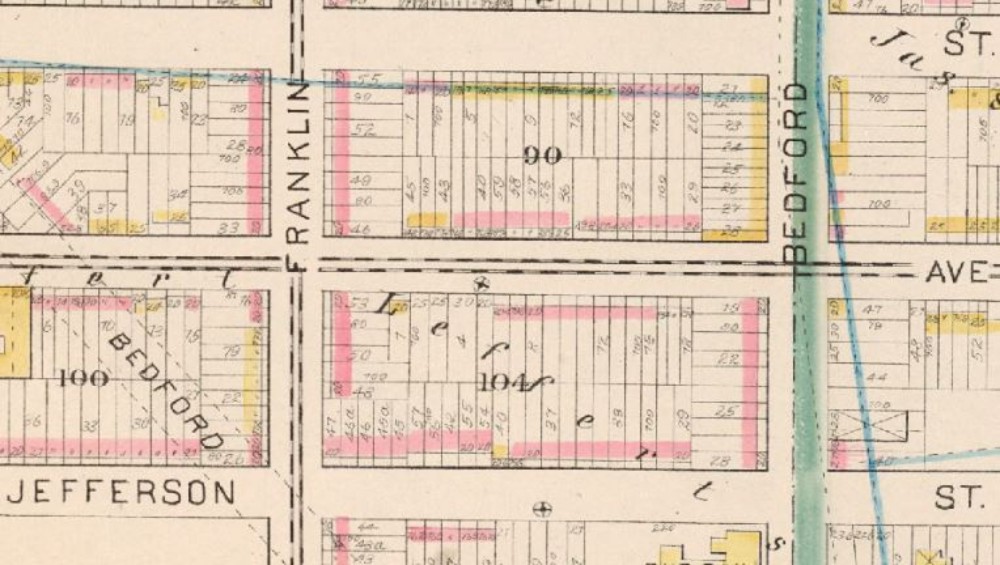

This group of four houses was built in the late 1870s. They appear in the neighborhood map of 1880, as do most of the houses on this block. They were part of the first wave of speculative development that took place in this area.

Everyone knew the Brooklyn Bridge would be opening up soon, and the flood of people wanting to live in Central Brooklyn would sweep through like a tsunami.

1880 map via New York Public Library

Early Bedford Speculative Housing

Most of the houses were modest, built for a growing range of middle-class buyers. These transitional Italianate/Neo-Grec houses are typical of this time period and style.

The invention of the pneumatic drill had made it possible to replace the traditional Italianate hand-carved acanthus leaf brackets with simpler mass-produced incised brackets and trim. The traditional incised floral elements of the Neo-Grec style had not been introduced yet.

The simple-yet-elegant carved lines are repeated in the wooden cornices, all remarkably in fine shape, considering they are close to 140 years old. The houses also have their original balusters and newel posts and some original fencing.

There are tiny dormer windows on top, with at least a bit of an attic and entrance to the roof. One homeowner put an addition on top, which ruins the symmetry of the row. At least they kept the cornice intact.

A Wedding Behind Private Doors

Not much beyond ordinary late-19th- and early-20th-century life occurred in these houses’ early years — except at 173 Putnam. This event shows the frequent prejudice and ignorance toward people not of Northern European descent.

In 1907 (the 20th century, for Pete’s sake) the house belonged to a Mr. J.M. Singleton. It turns out he was Chinese, and had become an American citizen, upon which time he changed his name. He belonged to the Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian Church, where he had a pew. According to the Eagle, there were other Chinese congregants there as well.

The paper reported on April 24, 1907, that it had received a postcard letting them know about the following: a young white woman, who had recently come into a sizable inheritance, was going wed a Chinese man the next evening at the house. The letter was signed “Hop Sing.”

According to the paper, the postcard announcing the wedding had been written by a woman. The writing “appeared to be much better than one would suppose an ordinary Chinaman would be capable of producing.”

The Eagle sent someone over to the house to find out what was going on, and Mr. Singleton answered the door and confirmed that his friend Kwai Pang was going to marry Miss Bertha Blumenshein at a house wedding the next day.

Mr. Pang was in his early 30s and had once been an employee of Singleton’s Manhattan cigar factory. Miss Blumenshein, who was 25, lived with her sister in Bushwick. She was very active in her church’s missionary work with the Chinese. The inheritance had come from her father, who had died several years earlier.

Mr. Singleton would not say more and did not let the reporter in the house. But the Eagle sent him back the next day to cover the wedding.

The next evening, groups of curious people stood around on the block, most of whom did not live there. The reporter said that every woman on the block had come out of the house to watch for the bride and groom.

The people at 173 Putnam were not answering the door to inquiring nosy reporters. Rumor had it that they were afraid of an incident. The wedding would have gone on anonymously had the Eagle not publicized it the day before.

Finally, as guests started to arrive, Mr. Singleton opened the door to answer reporters’ questions. He said the bride and groom were being married by the Rev. Hughes of the local Methodist Church. All the Chinese guests at the wedding were American citizens.

The reporter referred to both Singleton and the groom as “the Chinaman” at all times. Singleton assured the reporters that Kwai Pang was now also an American, a good and honorable man who was not going to beat his wife.

Singleton also told the reporters that he didn’t see what the big deal was. As he put it, a Chinese man was marrying an American girl. It happened quite often. The reporter felt the need to point out that yes, Miss Blumenshein was American, but she was of German stock.

When asked where they were going on their honeymoon, Mr. Singleton said he didn’t know. Maybe Canton or Berlin, maybe Harlem — it wasn’t any of his business. He also wasn’t answering any more questions.

The Eagle reporter noted at the end of the piece that after that the “secretive Chinaman” backed into his house and closed the door.

Hopefully, Mr. and Mrs. Kwai Pang had a long and happy life together.

[Top photo: Google Maps. All other photos: Nicholas Strini for PropertyShark]

Related Stories

Building of the Day: 67 Putnam Avenue

Building of the Day: 85 South Oxford Street

Walkabout: Architecture – The Neo-Grec Style

I believe that the JM Singleton discussed here is Joseph Singleton, whose background is discussed a bit in this article about a Chinatown fundraiser for Jewish pogrom victims: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/tien-hsia.php?searchterm=027_jews.inc&issue=027.

Wow. Local paper gets an anonymous tip [!] about a mixed-race wedding, takes it seriously, sends a reporter, publicizes the wedding, draws a crowd. All in Bed-Stuy, which I’d understood to be an integrated neighborhood back in 1907.

How did you find this story, MM? Did you encounter it fortuitously while looking for something else?

Lovely story……

I wonder what ever happened to the couple and the owner Mr. Singleton?