The Tale of a Pioneering African-American Father and Son: Rufus L. Perry Sr. and Jr.

Rufus Lewis Perry Sr. and his son, Rufus L. Perry Jr, were quite newsworthy in their day, breaking racial and social stereotypes.

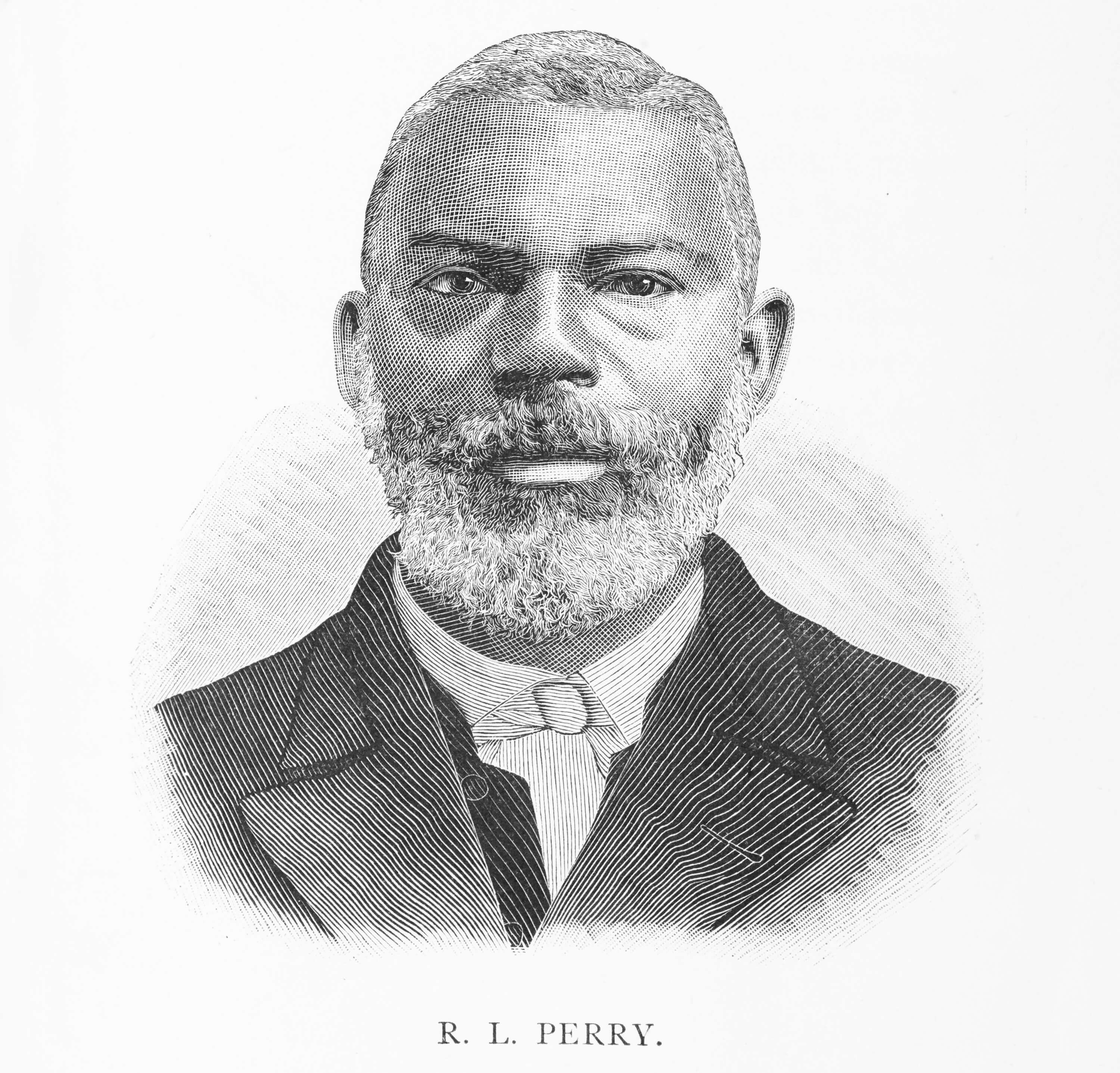

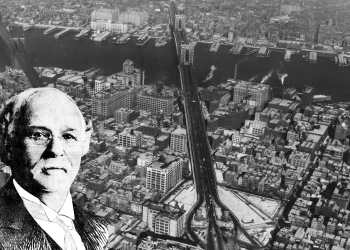

Sketch of Rufus L. Perry, Jr. via Library of Congress, sketch of Rufus L. Perry, Sr. via New York Public Library, map via New York Public Library

Editor’s note: This is an update of a series that ran in 2015. Read the originals here: Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

I often write about the movers and shakers of the 19th and early 20th century Brooklyn — they could be fascinating, and in their own ways, thoroughly modern people. Some of their names grace our streets, our schools, businesses and other buildings.

Most, however, are gone and forgotten, in spite of glowing like torches during their own times.

Rufus Lewis Perry Sr. and his son, also Rufus L. Perry, were quite newsworthy in their day. Between the two of them, their names appeared often in the Brooklyn papers between the end of the Civil War and the Great Depression.

During those years, they were the topics of pride, envy, derision, scorn and grudging admiration. Why? Their accomplishments were impressive and many.

But for too many Brooklynites, this proud father and son were too smart for their own good, too uppity and too grandiose, not exhibiting the proper humility expected from two sons of Africa. But that never stopped them.

Rufus Lewis Perry Sr. was the son of a slave, and was enslaved himself as a child. He was born in 1834 to Lewis Perry and a woman named Maria. Her last name has been lost to history.

Lewis and Maria were slaves on the Smith County, Tenn., plantation of Archibald W. Overton. Perry was a gifted mechanic and cabinetmaker. Because of his skills, he was able to hire himself out as a craftsman.

Instead of staying on the plantation, he was able to move his family to Nashville, where he worked independently, but with all of his earnings going back to Overton. This illusion of freedom for skilled craftsmen was not unheard of for slaves in many areas. It was not offered to all.

Young Rufus Perry was regarded as emancipated, and was eligible to attend a school for free blacks, where he learned to read and write.

But in 1841, his father couldn’t resist the lure of freedom, and took off for Canada, leaving his wife and child behind. Archibald Overton was furious, and brought Maria and young Rufus back to the plantation. For the first time in his young life, Rufus Perry was a slave.

Although young, he was educated, which made him dangerous. Ten long years later, he was sold to a slave trader who was going to take him further south to Mississippi. Young Rufus knew that if that happened, he was lost forever.

Three weeks later, he saw his chance, and escaped, successfully traveling north with the aid of the Underground Railroad, over the Canadian border to Windsor, Ontario.

He was able to enroll in school and further his education, and took a job teaching other fugitive slaves. In 1854, he decided to go into the ministry. He was accepted at the Kalamazoo Seminary in Michigan, and was ordained in 1861, at the beginning of the Civil War. He later went on to receive a Ph.D. in religious studies.

Rufus Perry was the pastor of the Second Baptist Church of Ann Arbor, Mich., and later pastor of churches in St. Catharines, Ontario and Buffalo, N.Y.

The Move to Brooklyn

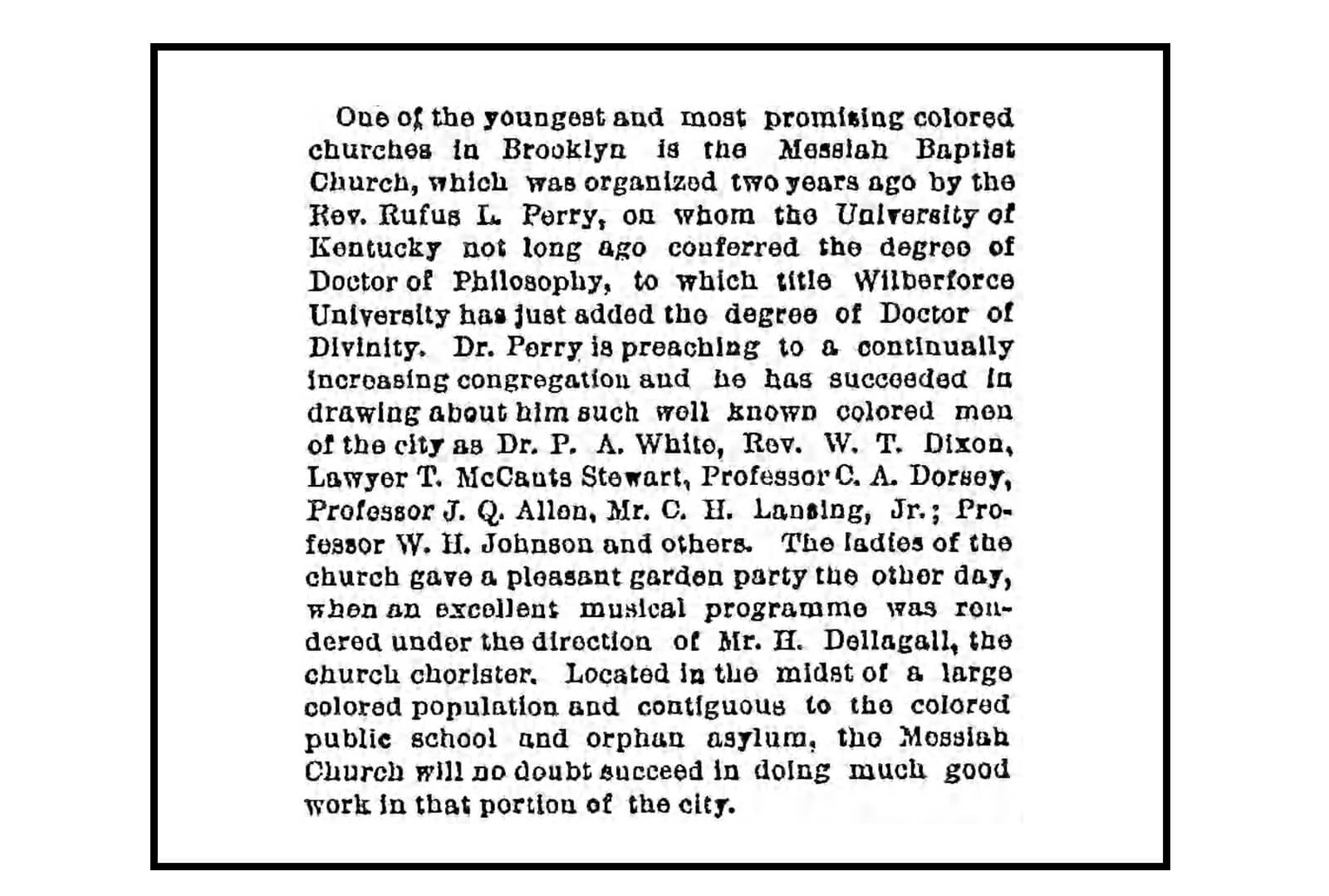

By 1870, he had moved to Brooklyn, where he organized the Messiah Baptist Church, which he pastored until his death.

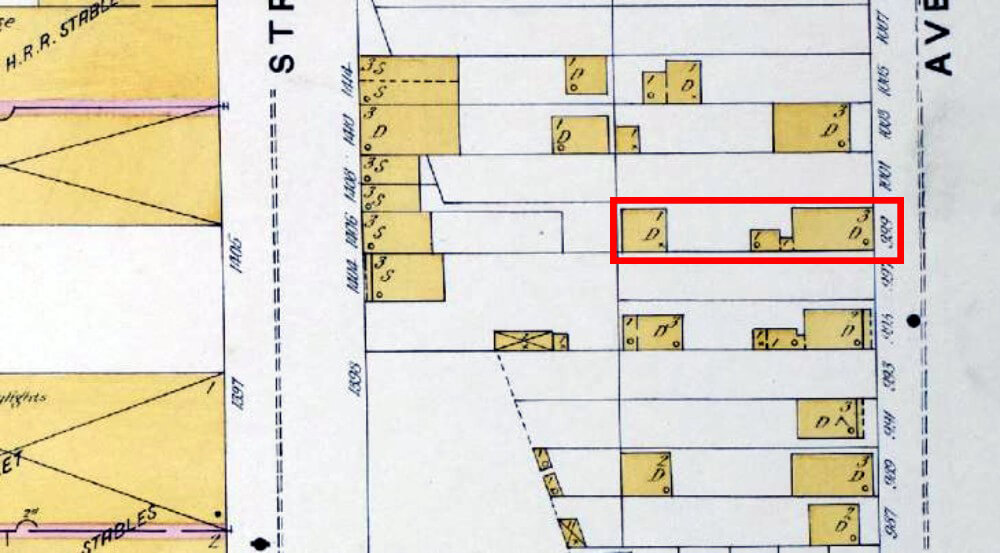

He and his wife, Charlotte Handy — whom he had met and married in Canada — settled in at 999 St. Marks Avenue in Crown Heights with their soon-to-be family of seven children. The house was a free standing wood framed house with an extension and an out building in the back.

Their house was directly across the street from the St. Johns Home for Boys, where the Albany Houses are today. Interestingly, they were one of three black families on this block when the 1880 census was taken.

Messiah Baptist Church stood on Dean Street, between Troy and Schenectady avenues, also in Crown Heights. This entire area was the westernmost boundary of the Weeksville community. The church was near the Howard Colored Orphans Asylum, the Colored School, and several other black churches.

For the next 20 years, the Rev. Dr. Rufus Perry was one of the leading voices in Brooklyn’s African American community. In fact, his influence went well beyond the city.

Between 1867 and 1879 he was the Corresponding Secretary of the Consolidated American Baptist Missionary Convention (CABMC), a large African American Baptist Mission organization. He was also co-editor of two publications for CABMC, The American Baptist and The National Monitor.

Perry was a powerful voice for the organization, a counterpoint to the often paternalistic attitudes of the white Baptist organizations that worked with Southern freedmen. CABMC felt that black missionaries and workers should be in the forefront of teaching former slaves.

During this same time period, Dr. Perry was also the vice president of the board that managed the National Theological Institute and University in Washington, D.C. This school was founded in 1864 to train black Baptist ministers.

As important as that goal was, the school failed in 1872 because of infighting between the black administrators and their white financial sponsors. One of those sponsors, a man named Justin D. Fulton, tried to get Perry removed from the board of CABMC, implicating him in some financial malfeasance.

However, the allegations were never substantiated and Perry was cleared. But the damage was done, and CABMC disbanded in 1879. Black Baptists would not organize again until after Perry’s death in 1895, when they organized the National Baptist Convention, which still exists today.

The Brooklyn Eagle had a robust religious readership. The paper could be counted on to chronicle the religious activities of a growing Catholic church, as well as the activities of the many mainline Protestant churches in the city. They also had a growing readership of Jewish congregants.

The paper often printed excerpts of sermons, or wrote articles summarizing talks given by all sorts of religious leaders. Many of Brooklyn’s clergy were quite well known outside of their own houses of worship.

They kept up with the African American population as well, surprisingly enough. The paper had an “Afro-American News” page, where church news was often disseminated.

Dr. Perry was well-known enough to transcend the Afro-American page, although they usually wrote “colored” when mentioning Messiah Baptist. He was often quoted along with the other famous ministers of the day. His sermons were also summarized or printed verbatim.

In 1893, the Embury Methodist Episcopal Church on Schenectady Avenue and Herkimer Street was moving to their new church on the corner of Lewis Avenue at Decatur Street. They sold their old building to Dr. Perry’s Messiah Baptist Church. Unfortunately, the building is no longer standing today.

In addition to everything else, Dr. Perry edited several publications for black Baptists, including The People’s Journal and a magazine called The Sunbeam. He supported the Baptist missions to Haiti, and wrote a book.

His book, The Cushite: or the Descendant of Ham as Seen by Ancient Historians and Poets, was published in 1893. It was an important work combining African history, Classical writings, and black Freemasonry to produce one of the earliest works of black cultural nationalism.

He argued that the ancient Egyptians and Ethiopians were the black descendants of the Biblical Ham, and were destined for greatness again, as were their modern day descendants and the African people.

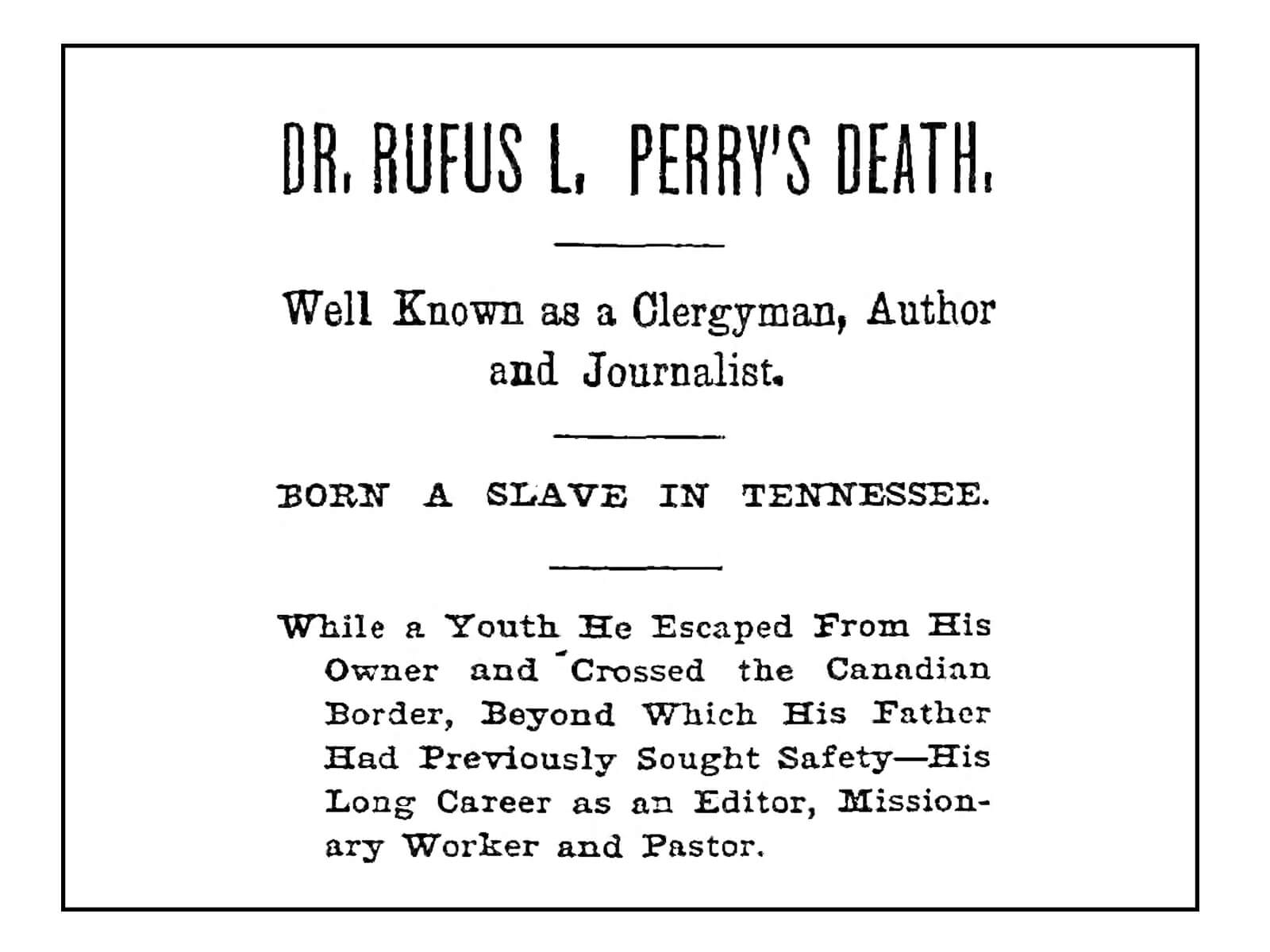

In June of 1895, the Brooklyn Eagle announced that Dr. Perry was dying. He was in a coma after being ill for a few weeks, and was not going to recover. The paper called him a “colored clergyman of considerable local note.”

He died on June 18, 1895, at the age of 61. The Eagle gave him full honors, including an illustration to accompany his lengthy obituary. They told of his childhood, his escape to freedom, and his many accomplishments as a preacher, teacher and educator.

It was quite an obituary, especially considering how poorly the Eagle generally treated most members of Brooklyn’s African American community.

His body lay in state at Messiah Baptist. The funeral was a private affair at the home, and the burial took place under the auspices of Concord Baptist Church, one of Brooklyn’s leading African American Baptist churches.

Rufus L. Perry Jr.

But as remarkable as Rev. Perry’s life story and accomplishments were, the world hadn’t seen anything yet. Dr. Perry imparted his considerable intellect and pride of people to his children. His oldest son, Rufus L. Perry Jr. would soon be a chip off the old block. He was already a lawyer practicing in Brooklyn when his father died.

Rufus Jr. began his life on May 26, 1868, born in Brooklyn when the family was living at 999 St. Marks Avenue.

Life for black folks in late 19th century Brooklyn was not easy. The law prohibited many overt forms of discrimination, but the reality was that most black people in Brooklyn lived on the fringe of society.

The schools and everyday life were segregated, and most African Americans were laborers or relegated to service jobs, while a small black middle and upper-middle class struggled to find acceptance and equality in the workplace and society.

The Perry family was part of this emerging black upper-middle class, which consisted of clergy, doctors, lawyers, undertakers, business owners and teachers.

Rev. Perry and his wife raised their children to believe that they were the equals of anyone. They were encouraged to aim high and become whatever they wanted to become in the world. They should not allow other people’s prejudices to hinder their progress. Young Rufus took that to heart. He was also really, really smart.

Rufus Perry Jr. matriculated through Brooklyn’s public schools, and then went to New York University for college and law school. He graduated from NYU Law at the top of his class in 1891.

He astounded his professors, and probably annoyed the hell out of his classmates, by writing his exams for entrance to the Bar completely in Latin. He also spoke and wrote fluent Greek, Hebrew and French.

His teachers were so impressed by his exams, they made copies and made all of the students read and learn.

Perry was asked to be the orator at his law school graduation and give the class speech. It was such a novelty for a black man to do so that the news made the New York Times, as well as papers across the state.

The Times noted that his speech was entitled “Liberty as Embraced in the Constitution of the United States.”

Rufus L. Perry Esq. was soon out on his own as a lawyer. He set up his offices at 375 Fulton Street, in the heart of the civic district.

For the next 30 years, he was “the Negro lawyer, Rufus L. Perry.” Sometimes he was the “Colored lawyer, Rufus L. Perry.” Every once in a while, he was simply Rufus L. Perry, lawyer. It all depended on where he was and who his clients were, and what papers covered his cases.

He had quite a varied roster of clients, black and white, male and female. The usual crowd at the courthouses got used to seeing “the Negro lawyer” there. He represented clients in civil and criminal cases, and he generally won.

His cases ranged from defending a young black woman who was accused of attempting suicide, an offense that could land you in jail, to representing a group of homeowners in Queens who sued the developer who built their houses.

He was able to have the charges dropped in the first case. The second case took place in 1906. Perry represented five Flushing homeowners who had purchased homes that were under construction. After moving into the completed homes, the homeowners soon found themselves with leaking roofs. On inspection, it turned out that the builders had substituted a cheap composite paper tile for the asbestos tiles specified.

Perry took the case to court and won. This was one of the few times in the papers that he was simply “lawyer Perry from Brooklyn,” with no reference to race.

Aside from his full schedule as a lawyer, Perry was also very much involved with varied other interests. He was a longtime correspondent to a French language newspaper published in America called Courrier Des Etats-Unis.

In 1906, he turned down a position in the consular office to Haiti. He did represent the president of Haiti, Pierre Nord Alexis, for several years, and was his official attorney.

He also continued his studies in Hebrew, and compiled a Hebrew grammar book.

In 1912, he made news around the country when he converted to Judaism. He had his first name changed to “Raphael.”

The newspapers were full of the story of the Negro who became a Jew. He was said by all to be the “first of his race to do so,” a claim that is by no means accurate.

Rufus Perry was a passionate defender of and advocate for the black community, and like his contemporary W.E.B. Du Bois, insisted that the white world treat him as an equal, both in the courtroom and in public. This stance caused some severe cases of ruffled feathers.

In 1899, he caused a stir when he proposed to establish a “Negro colony” near Jamesport on Long Island. He wanted to buy property and establish summer homes for well-to-do black families.

The horrified landowners of Jamesport vowed to do whatever it took to stop him. There wasn’t a lot of available land, and they promised to pool money to buy up every inch of it in order to stop the Negroes from establishing a beachhead there.

It turned out that Jamesport already had a small black population a mile away from town, in an area called “Cum City.” It was named after Cummy Boston, an 80-year-old man who had been the area’s first settler.

The hamlet consisted of about 10 houses along a road, with a church at the end. Boston and the other black families there had been employed as local farm workers before the area had become dominated by the second homes and estates of wealthy New Yorkers.

The Brooklyn Eagle sent a reporter out to Jamesport to get the opinions of the locals to the news of possible new neighbors. Boston, known by everyone as “Uncle Cummy,” was the only person interviewed who thought it was a great idea. “Golly, won’t that be fine,” he said.

A wealthy white landowner in Jamesport had an opposing view. “In my judgement, to dump a gang of Negroes who have been driven from the south because of the crimes of their own kind and for the misdeeds of themselves, into this delectable country is an outrage that beggars description and should be resisted by any person who has an interest in Long Island at heart.”

Perry seems to have abandoned the idea, probably more because he had so much on his plate than because of the racist negativity. He wouldn’t have had a problem taking on anyone who opposed him.

His insistence on equality for himself and those of his race made him a hero and role model in the black community, and his intelligence and skill in the courtroom garnered him much respect in the courts. But not everyone was impressed. Some thought he needed to be made aware of where his place really was.

A Life in Brooklyn Politics

Rufus Perry Jr. spent his entire life rising above the expectations of the white world around him.

In 1910, at the age of 26, Rufus married 24-year-old Lillian Sylvia Buchacher. Unfortunately, no other information is available about her. All we know from census records is that she and her parents were all born in New York City.

Interracial marriages were few and far between back then, and were not looked at favorably at all. Two years later, Rufus converted to Judaism, taking the Hebrew name “Raphael.”

He was black, Jewish, with a white wife, and with way too much smarts for the son of a former slave. When he decided to go into Brooklyn politics, his friends and enemies lined up accordingly. But first, a little background:

In the years before World War I, the African American community in the United States was struggling to rise above overt discrimination in the South, and a more covert racism in the North.

Although slavery had ended with the Civil War, most Southern blacks were still on plantations, now as sharecroppers tied to the land by debt. Illiteracy was still high, and other opportunities were low.

The KKK and other hate groups terrorized people who got out of line, and lynching and injustice were more common than real justice. A black man still couldn’t look a white man in the eye without risking reprisals later.

Here in the North, that sort of overt racism was seen far less often, but economic and social equality was not yet possible for most black folks. However, as a group, black people were not sitting around waiting for equality to be bestowed upon them.

Even during pre-Civil War days, there had been organizations and societies dedicated to self-improvement. The black church was a longtime leader in this movement.

In 1909, W.E.B. Du Bois — the first black man to get a Ph.D. from Harvard — and a group of black and white activists founded the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, one of the most important and powerful civil rights organizations in America.

Du Bois was the voice of “the talented tenth,” his name for the elite in the black community consisting of educators, professionals and the like. He believed that this group could help open the doors of equality and opportunity for the rest of the black community.

A man like Rufus Perry Jr. was certainly one of the “talented tenth.” His educational accomplishments, his victories in court, and his acceptance in the white legal community — albeit grudgingly at times — was proof that blacks were as capable of “higher” professions as anyone.

Brooklyn’s black community was also well aware of Perry’s talents and skill. In April of 1911, the Brooklyn Eagle printed a letter from Clarence A. Smith, an African American living on Lafayette Avenue.

“Why doesn’t Brooklyn have a Negro magistrate?” Smith asked. He went on to note that Brooklyn had 16,000 colored voters (this was before women could vote) and no representation. He felt that black support for New York Mayor Gaynor deserved to be rewarded by appointing Rufus Perry as a magistrate.

That question would go unanswered. In the meantime, Mr. Perry was still representing clients and cases that touched upon the black experience in the New York area. He was also thinking beyond the practice of law and buying investment property.

In 1914, Perry was the president of a group of black investors who purchased Avon Hall, a three-story building built as an event space and meeting hall. It was located at 1217-1221 Bedford Avenue, near Fulton Street.

Built in 1885, it had an auditorium, a ballroom, and a bowling alley in the basement. Today, it no longer stands. It was replaced by an automobile showroom in 1919. The newer building was a Building of the Day. The consortium had the building for two years, and then sold it at a tidy profit.

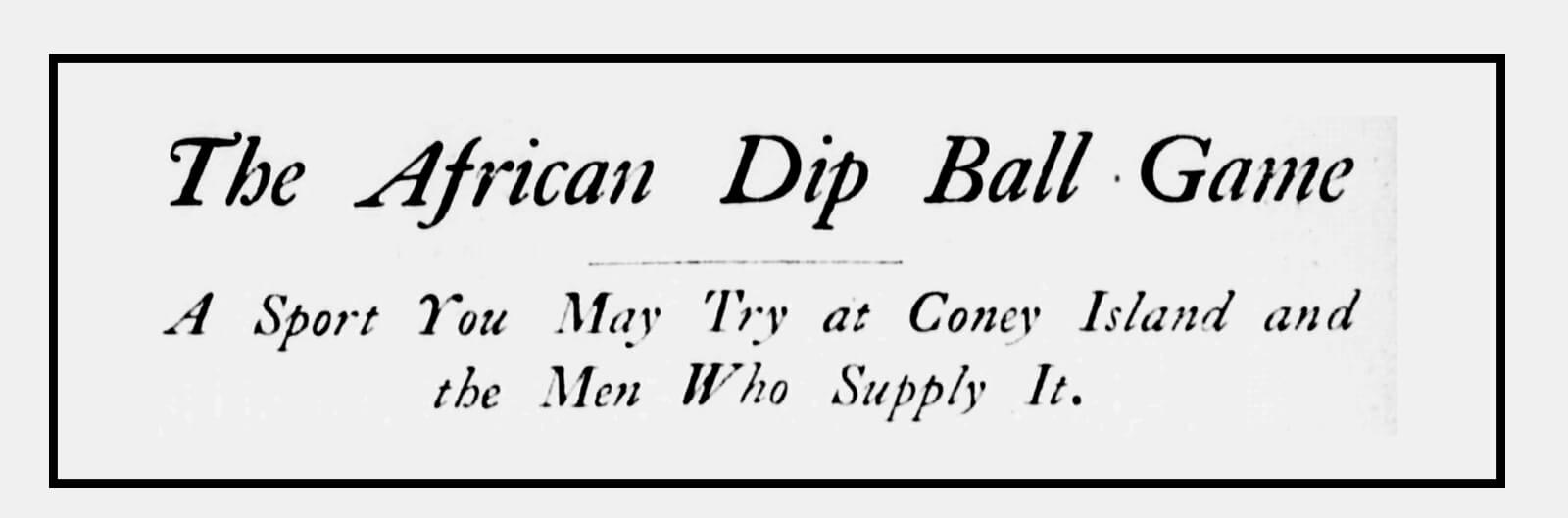

In 1915, while this was going on, Perry aided Assemblyman Fred G. Milligan Jr. and Senator Alfred J. Gilchrist in introducing legislation to stop the practice of “Negro ball dodging.”

One of the most popular attractions at Coney Island arcades was to hire black men to stick their heads through a canvas or plywood opening, while people payed money to throw baseballs at them. Desperate men would take the jobs, risking serious injury, even death.

The men wanted to make the practice illegal, and to make it a misdemeanor for anyone to throw the ball, or act as a target. The bill had wide support from the black community, as well as the general public. Thankfully, it was passed.

However, in 1917, Rufus Perry’s fast moving legal career came to a grinding halt. He was disbarred because of a trumped up charge, with much ado about a technicality.

The Rev. Rufus Perry Sr. owned a property at 1014 St. Marks Avenue, up the street from their home at 999 St. Marks. In 1895, just before his death, Rev. Perry wanted to transfer the deed to his wife.

According to his son, the elder Perry was so feeble at the time that he had his lawyer son rewrite the deed, and sign it for him. He then traced over the signature, thereby authorizing it. He died soon after.

Perry did not immediately record the deed, which was signed in 1895. When he finally did, he couldn’t find the original, and so filed a copy. That copy was dated 1895, but the paper had a watermark of 1896. He later found the original, and filed that, as well, intending to have the copy removed, but he forgot.

In 1917, Mrs. Annie Perry Mills, Rufus’ sister, wanted to sell the property. When the buyers’ had a title search done, the title company came upon the rewritten deed as well as the copy, and questioned their authenticity.

Perry explained what he had done. He also noted that he personally had paid the mortgage and the interest on the property for almost 20 years. It was now completely paid off.

The Brooklyn D.A’s office and the Brooklyn Bar Association were both looking into the case. They accused him of forging his father’s signature.

The D.A. wanted to charge Perry with both forgery and perjury. The case went before the grand jury, which determined that there was no perjury and no forgery. There would be no criminal charges.

But the Bar Association took a more jaundiced view. They ruled that Perry had indeed forged the signature on a legal document, and thereby acted in a manner unworthy of the Bar. They voted disbarment. His legal career appeared to be finished.

Perry immediately appealed, but the first appeal was unsuccessful. In 1918, the Appellate reviewed his case, and overturned the decision. But they suspended him for five years, citing his “good conduct” before all of this mess.

During his suspension, Perry was busy helping the cause of black soldiers in World War I. The army was still segregated, and black soldiers were not accorded the rights they should have had. They had inferior equipment, lodgings and other basic accoutrements. Returning veterans, especially wounded ones, found themselves without the same resources as white veterans.

Perry was somehow able to arrange a meeting with President Woodrow Wilson, in Washington, D.C. The two men sat for an hour at the White House, while Perry presented his case for the African American soldier.

The result was a $425,000 appropriation by the U.S. Government for the improvement of conditions and equipment for the colored troops. Not everything one could ask for, but a substantial realization by Wilson that more needed to be done.

In 1922, Perry’s suspension was lifted, and he was once again able to practice law. He got right back to his clients, old and new, and continued to make the papers.

In 1927, a group of supporters encouraged Perry to run for a judgeship in Brooklyn on the Socialist Party ticket. They took out an ad in the paper that cited his status as Valedictorian of his Law School class, his many achievements in court, as well as his work in French Literature.

He had been made a member of the Societé Academique d’Historie Internationale, and had been awarded a diploma and a Gold Medal for his accomplishments. If anyone was worthy of being a judge, it would be a man of the caliber of Rufus Perry.

He did not win.

On June 6, 1930, after a two-week illness, Rufus Perry Jr. died at his home at 1427 President Street. The article in the Brooklyn Standard Union announcing his death noted that he was the famous colored lawyer, the son of the Reverend Rufus L. Perry, Sr.

The article went on to note that he “attracted nationwide attention 18 years ago when he embraced the Jewish faith.” He had been a leader of Brooklyn Negroes for the Republican Party, but had then become a Democrat, and then ran for county judge under the Socialist Party.

The article did not note any of his many accomplishments – not his formidable skill in languages and scholarship, his membership in many important organizations and clubs, his meeting with presidents or his representation of foreign leaders. Nor did they mention any of his noteworthy court cases. Thankfully, they didn’t mention his disbarment, either.

But they did note that he was survived by his widow, Lilly S. Perry, “a white woman,” and a brother and sister. He and his wife never had any children. His funeral was at home, followed by burial at Mt. Carmel Cemetery. He was 60 years old.

A full and fascinating life reduced to private matters of faith and whom he married.

Today, the Perry men, father and namesake son, would be even more forgotten, had it not been for the efforts of Freedom Williams, the great-great grandson of Rev. Perry. Mr. Williams. He has established a website highlighting some of the accomplishments of his ancestors and important biographical information. It can be found here.

Rufus Perry Junior’s many cases would make a fascinating study. Hopefully the opportunity to further investigate this matter will arise.

Related Stories

- Black Folks in 19th Century Brooklyn

- Slideshow Highlights African American Landmarks

- The Inspiring Story of Weeksville, One of America’s First Free Black Communities

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment