Celebrating Christmas in 1899: A Tale of Two Brooklyns

The Brooklyn Christmas of 1899 was not so different than today, a tale of the haves and the have-nots.

A circa 1906 Christmas postcard. Image via New York Public Library

Editor’s note: This story is an update of one that ran in 2013. Read the original here.

Many of our American society’s most enduring Christmas traditions come from the Victorian Age. Our idea of Santa Claus, the giver of gifts, became fully imagined in the 19th century. From mid-century England we got Dickens’ London, with its top hats and tail coats, Christmas dinner and Tiny Tim. From Scrooge, Marley and the ghosts we had the quintessential example of greed and stinginess being redeemed into charity and giving by the miracle of love, family and friends. Our European Christmas traditions continue with carols, music and decorated Christmas trees, a Teutonic tradition made popular by Queen Victoria and her German-born Prince Albert. And then we added some American traditions of our own.

The last Christmas in Brooklyn in the 19th century was typical of its day, and not so very different from the present. Modern 21st century folk would feel right at home there, because in all the ways that matter, our society is very similar to what it was in the late 19th century. Brooklyn was now a part of greater New York City, and New York City then, like now, was a society of haves and have-nots. Some people were doing really well, and their children enjoyed a Christmas filled with fine clothing, expensive gifts, lots of food, and grand and gracious living. While only blocks, or a neighborhood away, other children were thrust into adulthood far too early, concerned not with toys but with survival. Many had no families and depended on the charity of others to live. Others were their families’ only means of support. Christmas 1899, like most Christmases, was a tale of two cities.

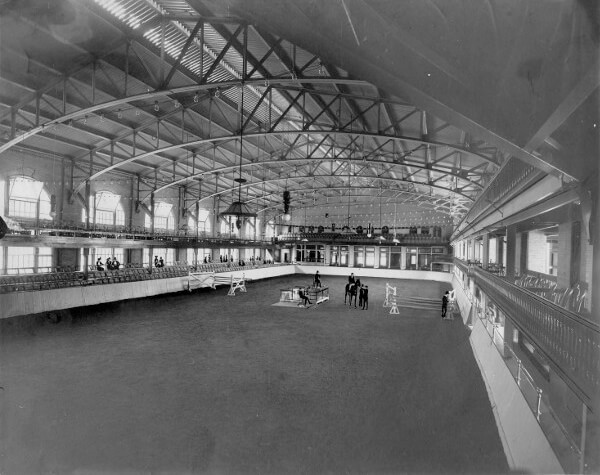

On Christmas Eve in Park Slope, Santa Claus was having difficulty with his sleigh. He was on his way to the posh Riding and Driving Club on Plaza Street, near Grand Army Plaza, to give gifts to a group of lucky children who were part of the junior riding club. The Riding and Driving Club was Brooklyn’s most exclusive equestrian sports club, with a members list that read like a Who’s Who of Brooklyn’s elite. Santa, who was in reality the club’s riding master, Harry Taylor, was at the reins of a double sleigh being pulled by four fine horses that were bedecked with sleigh bells. The horses were attired in red coats with white trim, and Santa himself also was in a long full length red woolen coat, trimmed in white fur. He had a long white beard and long hair.

As his sleigh approached the Riding Club, it got stuck in the sand in front of the entrance. When Santa and his helpers tried to pull the sled out, it got mired in the mud and it broke. Literally. The sleigh fell apart, so Santa had to transfer his bag of goodies, as well as a red coat and the sleigh bells, to one of the horses in the stable. He rode into the club’s riding arena, packed with children, looking more like Wild Bill Hickok than Santa, but the kids loved it.

Several of his helpers brought in most of the bags and baskets of gifts, but Santa thrilled the audience by riding around the ring a couple of times, and then dismounted to distribute gifts. All of the kids who were riding in that day’s special program got special presents. The girls all received a silver mounted tortoiseshell comb and the boys all got a solid silver key ring. All of the children in the room received boxes of candy. After Santa had finished, the rest of the afternoon was spent in games on horseback, as well as on foot. A wonderful time was had by all, and the children left exhausted, but full of holiday cheer. Most of the horses belonged to the club, but several of the children owned their own horses, which were boarded at the club. All of the horses received a special holiday treat, too.

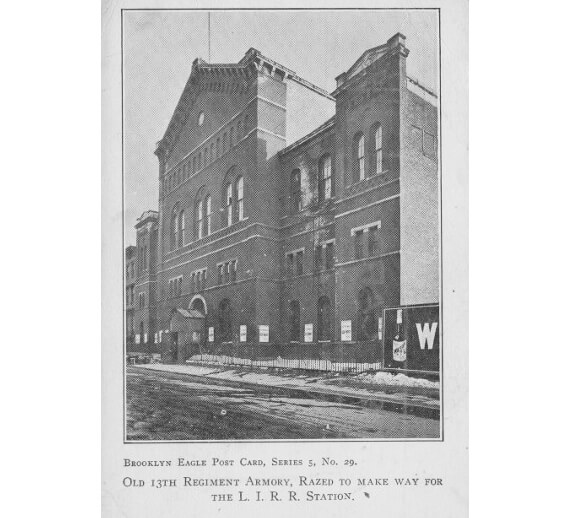

Across town, on Christmas Day, a special holiday treat was being enjoyed by a very different group of children, many of whom would have been glad to have been living as well as the Riding Club’s horses. Over four thousand children filled the drill hall of the old 13th Armory at Hanson Place and Flatbush Avenue for the annual Christmas dinner sponsored by Mrs. Sittig’s Christmas Tree Club, one of the most respected and well supported of Brooklyn’s many charities.

Mrs. Lena Sittig, the wife of a successful wholesale grocer, founded the Brooklyn Christmas Tree Club in 1892, to provide Christmas to poor children who would otherwise have none. She was quite active in Brooklyn’s social life, and also had a successful career as a writer and correspondent. Mrs. Sittig was an accomplished musician, and friends with all of the most important musicians and performers in the city. The childhood death of one of her two children had inspired her to help less fortunate children at Christmas, that time of year when poverty was felt by children and adults the most.

She recruited her wealthy friends, male and female, to donate money, and her music and theater friends to donate their services and talents, and they put on an all-day Christmas show for a large group of children, followed by a many course meal, where the children were told to eat anything and everything they wanted. At the end of the day, each child was given a gift of a toy, and a bag with an orange, some candy, and other goodies to take home. Many kids also received hats, gloves, scarves and other clothing.

The first Christmas Tree Club in 1892 was a huge success, and each year afterwards, the committee planned a larger and larger event, in order to serve more children. In 1899, there were two entertainment venues as well as the meal. The event that year was so large; they required the drill hall of the former armory building to hold everyone.

The club had grown to the point where they were working with other organizations to provide every service for the party. That year, the Salvation Army was responsible for cooking the meal that would feed thousands. Many of the children were orphans, living in Brooklyn’s orphan asylums and refuges, like the Newsboy’s Home, run by the Children’s Aid Society. Many of these children spent their days hawking newspapers, running errands, selling matches and flowers, or working in factories.

Some were truly orphans; others had parents who could not afford to take care of them, or were in prison or on the street themselves. Some of the children at this event still lived with their parent or parents, but were desperately poor, and were in some cases, the sole breadwinners of the family. But that day, they were just kids. First the children were entertained by shows that featured skits, clowns, trained monkeys and singing and dancing. The entertainment took place at the Grand Opera House and the Park Theater before the meal at the armory.

The Armory seated 1,800 kids at a seating. The children stood there stunned at the sight of tables groaning under the weight of platters of food, bowls of fruit, and baskets of bread. They stood there and stared at it until they were encouraged to sit, and have whatever they wanted. They cleaned up, many tucking more than one treat under their shirts and aprons for later, or to give to family. They moved out, and the next group of 1,800 children was seated.

As the children left the dining room they gathered in another room where each girl received a doll and each boy a toy. The dolls all had clothing made especially by Mrs. Sittig’s doll committee which had worked all year for this day, and the toys were also specially made or donated by individuals. Children were also given gifts of clothing, especially scarves, hats and coats, all collected throughout the year by the committee. The exhausted and laden children, and their parents or care givers, then took them back home, happy, at least for a day.

Mrs. Sittig had appealed to the best of Brooklyn’s generous nature. Transportation was donated by the trolley and railroad companies, the children and their adult companions all received free rides that day. Many of Brooklyn’s hotels had donated space during the year for the club’s meetings. Food and treats were both donated and purchased, and even the dish towels used that day were donated.

All of the performers, including Santa Claus, donated their time and talents. Santa was often one of New York’s premier actors, and that year, Mr. Frank Sittig, Lena’s husband and a dedicated member of the club, was also one of the Santa’s. Printers donated paper and printing services for the day’s program, and some also offered their services at no charge to the club during the year. Whatever the need, Mrs. Sittig or one of her club members, had persuaded someone to provide it.

As a new century approached, the children of Brooklyn, at least for one day, all went home and were tucked snug in their beds, with visions of sugar plums, turkey with all the fixings, cookies, cakes, baskets of bread, toys, clothing and, for some, silver keychains dancing in their heads. May the spirit of Mrs. Lena Sittig, her Christmas Tree Club, and all those who spent their days thinking of others on that day long ago remain with us and inspire us to do in kind. Merry Christmas, Happy Holidays and Happy New Year.

Related Stories

- Where 19th Century Brooklynites Got Their Christmas Trees

- The Dazzling Dyker Heights Christmas Lights of 2019 (Photos)

- A Snapshot of Brooklyn Hanukkahs Gone By

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment