Walkabout: “The Great Mistake” — How Brooklyn Lost Its Independence, Conclusion

We conclude our look at the “Great Mistake,” the creation of Greater New York City, and the end of an independent Brooklyn. Part One of our story gave the background of the move to consolidate and Part Two explained why it was so important to New York City. Now, the aftermath. What must have it…

We conclude our look at the “Great Mistake,” the creation of Greater New York City, and the end of an independent Brooklyn. Part One of our story gave the background of the move to consolidate and Part Two explained why it was so important to New York City. Now, the aftermath.

What must have it been like to wake up in Brooklyn on January 1, 1898, and realize that you were not in an independent city but instead part of Greater New York City? To be no longer the captain of your own team, but now a player on someone else’s?

I would imagine for most people, especially the average working man in New York, the consolidation meant nothing, and it was just another New Year’s Day. Some Brooklynites embraced the change, eager to take advantage of the opportunities offered by the new rules.

But those who were dead set against the whole thing raged, mourned and took pen in hand to complain, unable to do much more than stand, like Lee at Appomattox, and surrender their sword, outvoted, outgunned and defeated.

The Brooklyn Eagle printed a lengthy complaint from one of these men, a citizen of Brooklyn who signed his letter “One to Serve.”

“What would be the vote if Brooklyn’s citizens could vote again? Secession would be our rule. We would declare ourselves to be the City of Brooklyn, and that by an overwhelming vote… If we stay where we are and see taken from the borough offices everything that looked so promising in the massive charter to the citizen of Brooklyn, what satisfaction will it be? Where are we to get compensation for the great sacrifice we have made? What will be our reward? Will there be any? Will not the future generation arise up and condemn us to the surrender of the charter of a great city to become only one-fifth part of another city, whose moral forces were not to be compared to the City Of Churches?”

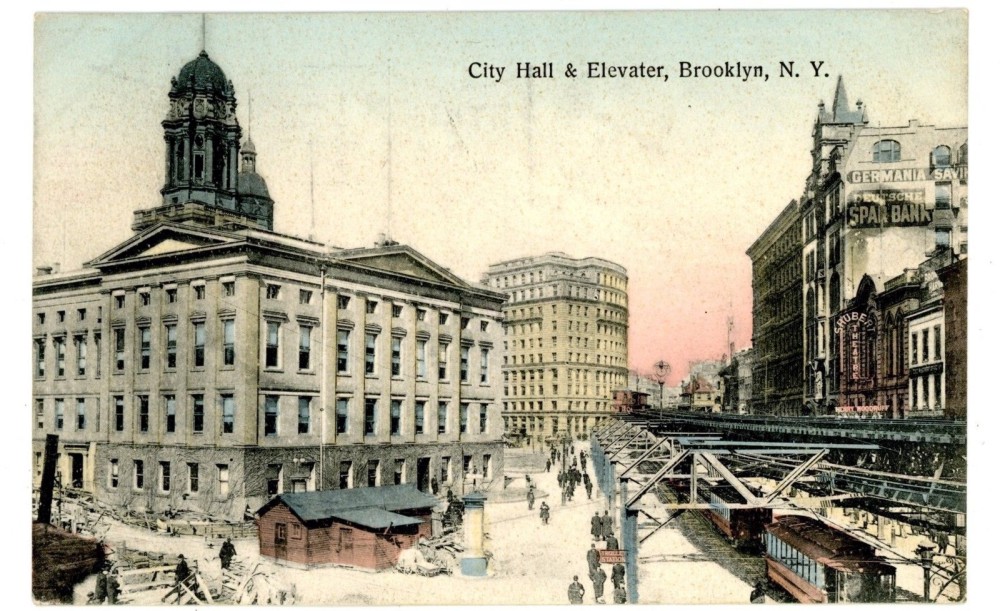

Brooklyn City Hall postcard, pre-1898

He goes on to talk about secession and talks about Brooklyn and Queens joining as one city, across the river from Manhattan.

“This would give us space enough to build the largest city on this continent. What a glorious city could be made on this island, surrounded as these counties are on four sides by river, sound, bay and ocean, we could make harbors and docks for the shipping of the world, and with the wisdom gained from the experiences of the old world, make a city the peer of any in this great land…Out of Kings and Queens counties we could in a few years make a city that would be superior in many ways to the city on Manhattan Island can ever hope to be…Let us be up and about this business at once.”

Well, interesting idea, that, but it obviously never took hold. Incidentally, when Queens was annexed into Greater New York, there was no Nassau County. Queens County went from Long Island City to the Suffolk County line. The towns, villages and farms on the far eastern end of the county had to petition for a better division, and Nassau County was created in 1899.

Ironically, the suburban towns that became a haven for New Yorkers fleeing the city, only 50 or 60 years later, almost stayed part of that city. That could have changed New York in major ways, and perhaps the city would be very different now.

For those in Brooklyn who feared the horrors of Tammany Hall politics, the leadership of Greater New York confirmed their predictions of business as usual. The first mayor of the newly expanded city was Robert Van Wyck, brother of Augustus Van Wyck, New York State Supreme Court Justice and the Democratic candidate for governor of New York who ran against Theodore Roosevelt in 1898.

The Van Wycks were one of the oldest Dutch families in New York, and Robert lived on Hancock Street in Bedford for a time. He was a successful lawyer and man about town who enjoyed traveling and the good life, and he’d been Chief Justice of the City Court of New York when chosen to run for mayor by Tammany Hall boss Richard Croker.

As mayor, he is credited for bringing order to the many municipal fiefdoms that made up the new city and for approving and championing the first subway line to be built in the city. He also set up the groundwork for the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel.

In spite of those laudable achievements, he is remembered primarily for being a lackluster mayor, chosen by Croker for being the kind of man who would not make waves or interfere with Tammany’s many other concerns in running the city.

Van Wyck did himself in with a huge incident called the Ice Trust Scandal of 1900. He backed the American Ice Company when it announced that it was doubling the price of ice from $0.30 to $0.60 per hundred pounds.

In the days before refrigeration, ice was used to keep everything from milk to meat to medicine cool, and doubling the price would keep ice out of the hands of everyone except the well-off. The outcry was immediate and strong.

Political rivals prompted a newspaper investigation, which showed that the American Ice Company had been given a monopoly; it was the only ice maker allowed to bring ice into New York piers.

Not only that — Mayor Van Wyck was supplementing his mayoral salary of $15,000 with $680,000 worth of American Ice Company stock that he did not pay for.

The American Ice Company had to back down and Van Wyck’s political career was over.

Tammany Hall was not pleased with him. It wasn’t because of the influence peddling and payoffs — they wrote the book on those practices — but because he had angered their political base, the poor immigrants who would not have been able to buy ice, and who had been promised that Tammany had their back.

In 1901,Tammany lost power to Brooklyn’s own Seth Low, who ran under a reformist platform. The New York Times later called the Van Wyck administration one “mired in black ooze and slime.”

The Van Wyck name still lives in the city, with an expressway, a school and two subway stops in Queens bearing his name.

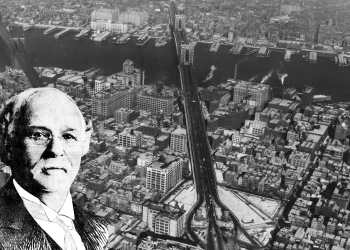

The effects of consolidation were many; some good, some not so much. Transportation and infrastructure improved, with subways and roads able to cross boroughs and bring people, goods and services anywhere in the city. It took years to coordinate this, but Andrew Green’s ideal of One City did take place.

Other municipal services — among them sanitation, police, social services and surface transportation — became single citywide agencies. One comptroller’s office regulated all of the city’s tax rates and budgetary concerns.

One central government took the place of many localized governments, with a mayor and other officials supposedly concerned with the well-being of ALL New Yorkers. Greater New York City became the second-largest city in the world, surpassed only by London in size and population.

Chicago was relegated to “Second City” status, and was no longer a threat to NYC sovereignty.

As we all know, however, bigger is not always better. Centralized government became exceedingly Manhattan-centric, a complaint that still is voiced today.

How does the new popularity of Brooklyn, now the most-talked-about city in America, factor into this? Could we have survived as an independent city?

Would we be like Minneapolis and St. Paul, two cities across the river from each other, more or less equal in most ways, or more like Philadelphia and Camden, one rich, the other not? Many of us still refer to Manhattan as “the city.”

Was this ever “Greater New York City” or was it really “the Great Mistake”? The debate continues…

A version of this story originally posted on December 8, 2011.

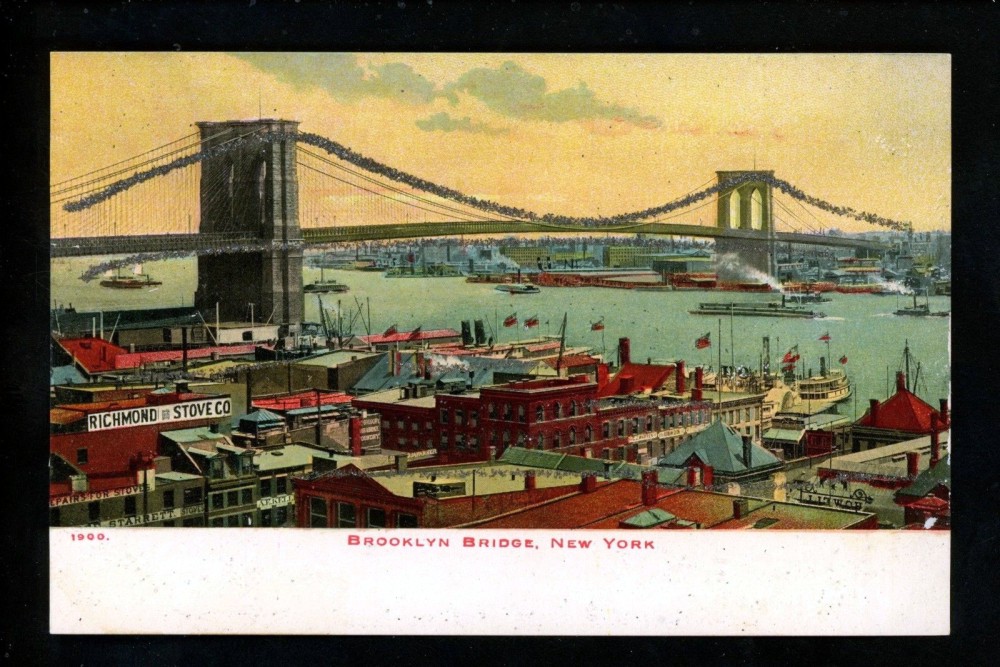

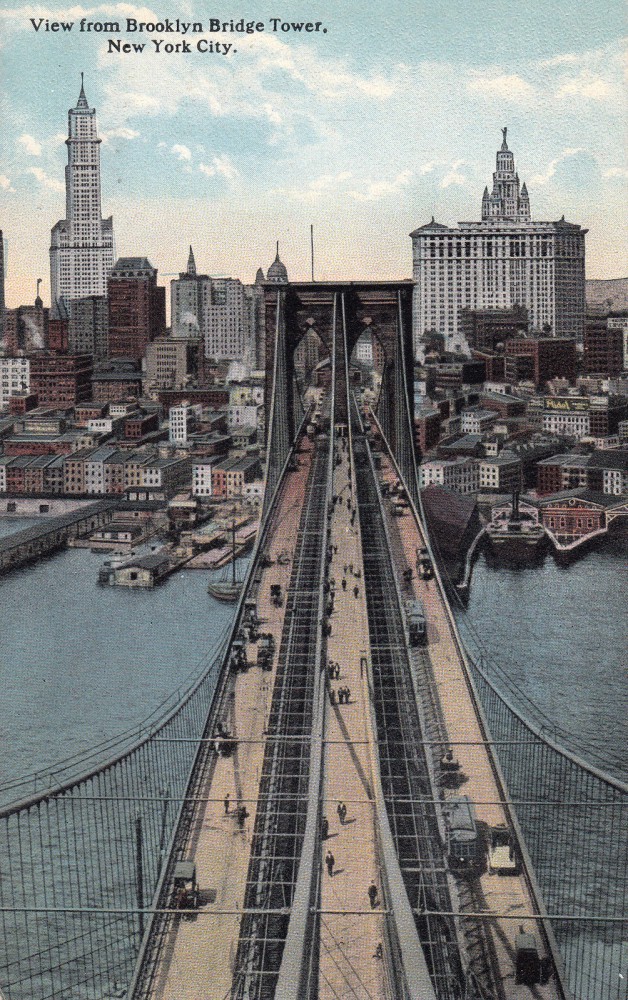

All postcards via Ebay

Crossing Brooklyn Bridge, 1905, via Museum of the City of New York

Related Stories

Walkabout: “The Great Mistake” — How Brooklyn Lost Its Independence

Walkabout: “The Great Mistake” — How Brooklyn Lost Its Independence, Part 2

Walkabout: Policing the “Great Mistake,” Part 1

Great series, MM. Unless we Brooklynites would really miss being able to say we live in New York–which I guess is baked into the deal–I can’t think of any downside to a separate cities. St. Paul to Manhattan’s Minneapolis would be just fine for people on this side of the river. From what I know of the Twin Cities, MSP has its problems but none stemming from its two-cities identity.