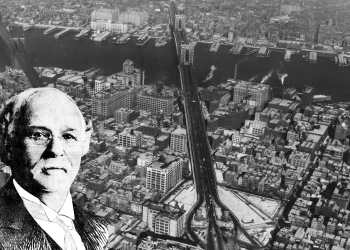

The Luxurious Wedding and Remarkable Home of Great Brooklyn Architect Montrose Morris

Even today, having your wedding covered by a prominent newspaper is a coup. For socially prominent Brooklynites in the late 1800s, everyone who was anyone vied to have the Brooklyn Daily Eagle report on their ceremony and reception.

Even today, having your wedding covered by a prominent newspaper is a coup. For socially prominent Brooklynites in the late 1800s, everyone who was anyone vied to have the Brooklyn Daily Eagle report on their ceremony and reception.

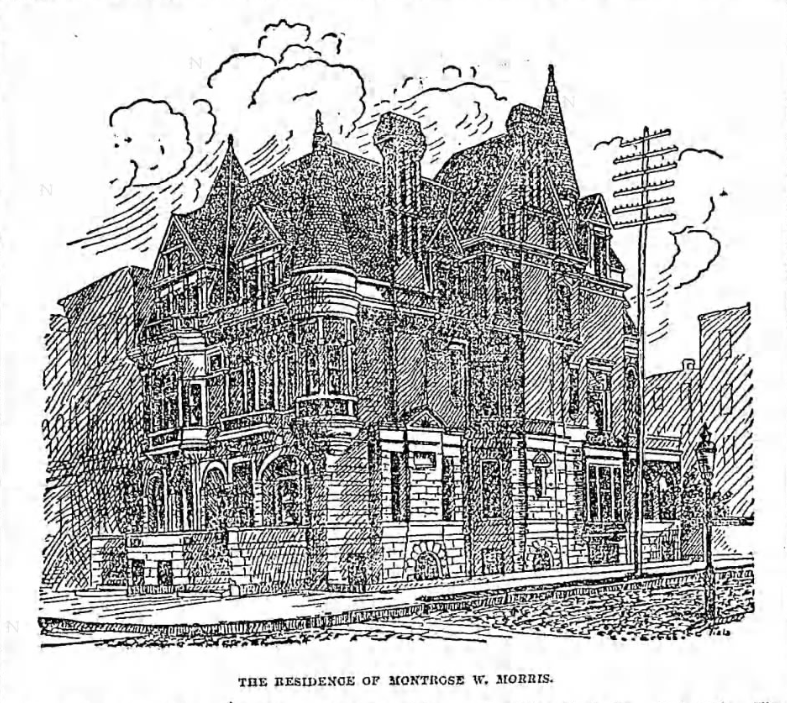

For the 1889 wedding of Miss Florence Gould Travis, however, readers were also treated to an epic description of her lavish new home. Florence was not just marrying one of Brooklyn’s finest, most sought-after architects.

She was marrying the great Montrose Morris. And their home was spectacular.

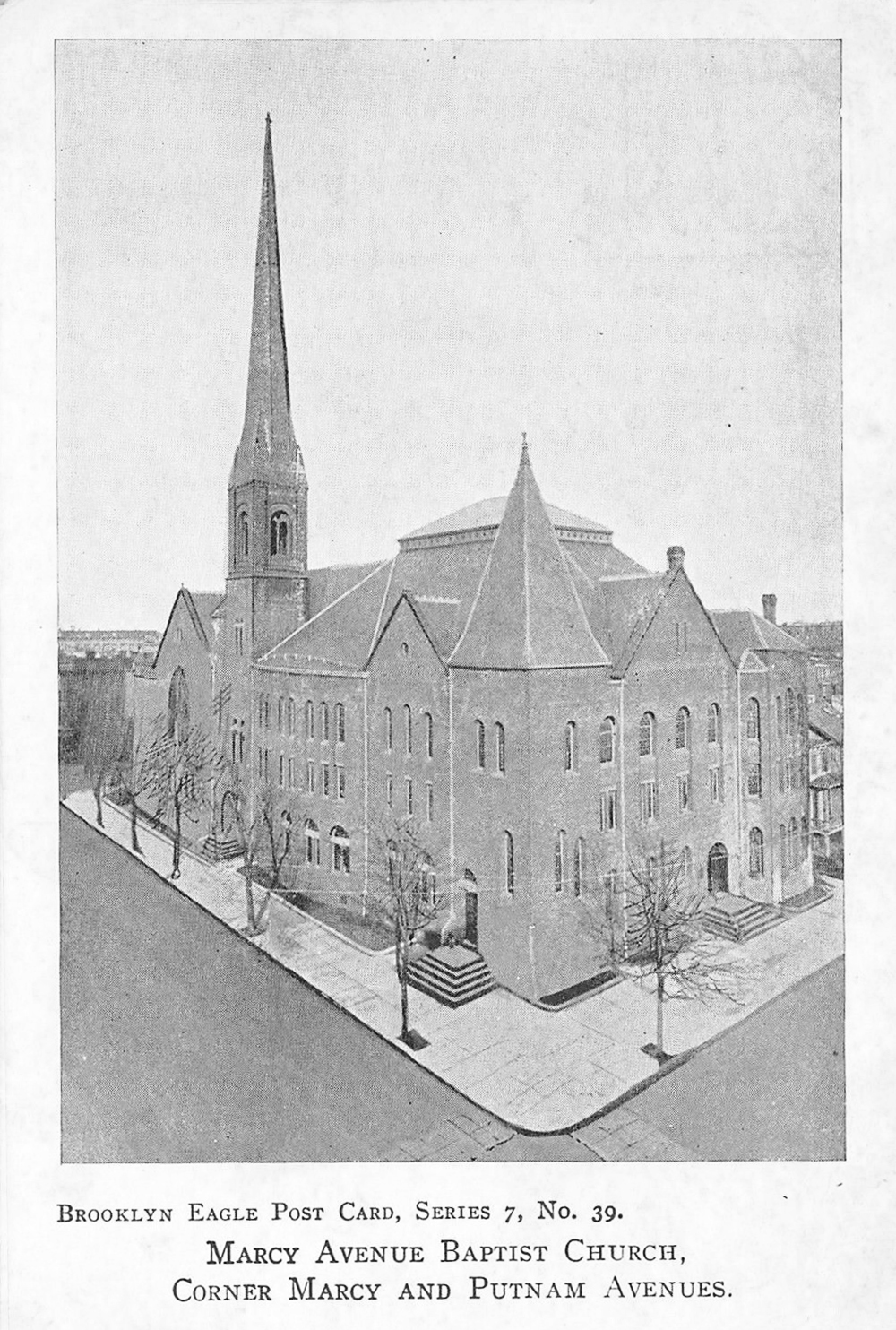

At 8 p.m. on November 14, 1889, Florence walked down the aisle of the Marcy Avenue Baptist Church, in Bedford, to meet Montrose Morris at the altar. The bride was accompanied by a maid of honor, four bridesmaids and two flower girls — the latter her younger sisters. Mr. Morris had six ushers and his best man at his side.

Florence’s gown was extravagant — white faille francaise, with an embroidered front of white mousseline de soie and pearls, and a satin brocade train. She had a long veil attached to a crown of orange blossoms, and carried a bouquet of white chrysanthemums.

The description of the ceremony takes up just a couple of paragraphs in one of the longest wedding articles I’ve ever seen in the Eagle. The rest of this substantial story is detailed, a room-by-room account of the grand Morris house at 234 Hancock Street. And there were a lot of rooms.

The Marcy Avenue Baptist Church was only two blocks away from the Morris home, and guests were invited to a lavish reception there. The elegant architectural beauty on Hancock Street was specially designed and built by Morris for his bride.

The home — and its coverage in the papers — was also his best method of advertising.

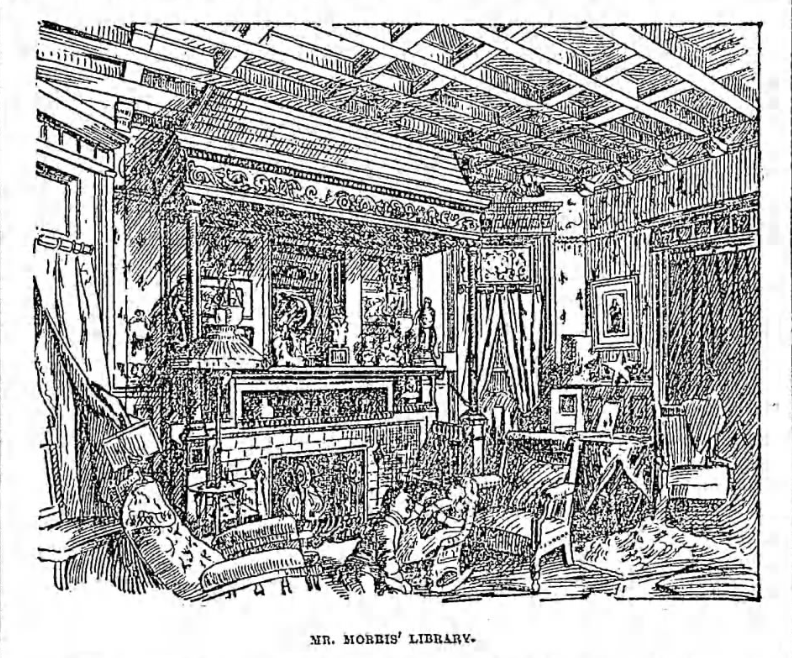

The library was extravagant and ornate.

Stained glass paneled doors opened into the entrance hall with coffered oak ceilings, high wainscoting, and a recessed seat with a heraldic coat of arms. The hall lead to a large reception room and two-story library with a balcony up to the second floor rooms.

The balcony was supported by heavily carved brackets. Down below, in the reception room, there was a large fireplace with inglenook seating and built-in bookcases.

A staircase rose up on one side, surrounded by pillars. Two iron crane lanterns lit the stairs. And there’s more: In the center of the 22-foot-high paneled ceiling was a gorgeous stained-glass dome illuminated by artificial light.

At the end of the reception hall, a stained-glass window depicted lily ponds with reeds and cattails and trees in the foreground, mountains rising in the distance.

The rest of the parlor was just as ornate — there were fabric hangings, built-ins, carpeting, hand-painted wall coverings, draperies, and chandeliers and sconces of ormolu, gold and onyx.

Elements of the dining room came from a German castle.

Guests then entered the octagonal dining room — which featured hand-painted metal walls taken from a castle in Germany — with paneled ceilings that had hand-painted metal inserts.

Rounding out the room was a fireplace and more built-ins, and a bay window, the entire room was sumptuously swathed in silk draperies. The Eagle reporter also got the run of the house, going upstairs to inspect the bedrooms, bathroom and sitting room — all quite elegant and ornate — although much more subdued than the parlor floor.

The sitting room was decorated in the popular Japanese-influenced Aesthetic Movement style.

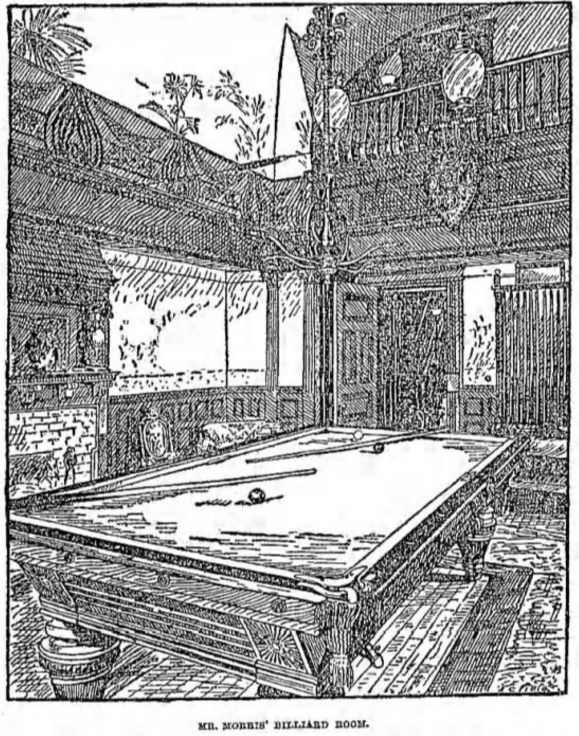

The billiard room was a work of art in itself.

On the third floor, in the front of the house, a billiard room awaited male guests. This 20-foot square room had an 18-foot ceiling. The side walls, above the dado, were ornamented with bamboo decorations and a mountain and sky effect in the background.

Around the sides of the room rose 12 Corinthian columns, supporting the entablature of another glass domed ceiling. A polished iron chandelier hung beneath the dome, held by four ropes through rings at each corner, and supporting four lanterns over the billiard table.

To the right there was a large Dutch fireplace with chip tile and an ornate carved mantle bearing the inscription: “good friends, good fire and good cheer.”

A stairway led to another balcony above the billiard table from which the ladies could watch the game. Around the side walls of the room were built-in benches with plush covered cushions.

Another bedroom and bath took up the rest of this floor. The top floor had a guest room, dressing room, servant’s room and trunk room. The basement (ground floor) held the kitchen, butler’s pantry, store room, wine cellar, furnace and servant’s office. A service stair also ran up the back.

Everyone in Brooklyn was impressed by Montrose Morris’s house. And his wife.

The article goes on to say that guests were extremely impressed by this opulent showplace, and said, “What a lucky bride,” until they saw the beautiful Mrs. Morris, surrounded by flowers that were arranged everywhere in the house, and her bridesmaids. Then they said, “lucky man!”

The couple went to Chicago, San Francisco, Mexico and Cuba for their honeymoon of nine weeks.

They were showered with expensive gifts of gold, silverplate and jewelry, and ended their reception with a supper taken on the balcony of their billiard room, with their closest guests below, receiving showers of flowers and rice from well wishers.

The couple would eventually have three children and remain married until Morris’s death in 1916. Florence would move to Long Island, where she died in 1933. Both are buried in Green-Wood Cemetery.

But this spectacular house did not survive.

The architectural showpiece at 234 Hancock Street burned down in the 1970s, leaving just an empty lot.

We know Morris used his house as a showroom, and it was his best marketing tool. So much so that many of the elements of this house were used again in his other commissions. His wainscoting, paneled ceilings and inglenook and hooded fireplaces are characteristic of most of his homes, and some can be seen today.

The grand billiard room — with the balcony and carved fireplace, with good friends, good fire and good cheer — can be seen in the newly restored billiard room in the Hulbert Mansion, now the Poly Prep elementary school, on Prospect Park West in Park Slope.

He also replicated his two story reception room in the house he built next door to his, on the corner of Marcy Avenue, at 232 Hancock Street. Although much altered, 232 retains many of the design elements that Morris’s house had — including the basic design of the facade. The few photographs that exist showing the two houses side by side, looking, as Montrose Morris houses often do, like a larger single entity.

This story has been edited and updated since its initial publication.

Related Stories

Suzanne Spellen, aka Montrose Morris, Is Writing Brownstoner’s First Book

All About Montrose Morris, Brooklyn’s Great Apartment Architect

Feast Your Eyes on the Finest Luxury Apartment Buildings of Gilded Age Brooklyn

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

Not much in the face but wow, that is the smallest waist. Probably rivals Scarlett O’Hara’s (17 inches)

I love this one! Great drawings from the Eagle!

LOL with that facial hair and haircut montrose morris looks straight out hipster central casting!

Thanks! Very interesting, loved this piece.

Mopar, those hooded fireplaces seemed to have been very popular in the 1890’s. Montrose Morris used them a lot, but so did Magnus Dahlander, George Chappell and others. In the above photos you can see the original in MM’s house, there on the left, with the built-in seat, and the fireplace in the lower left photo also has the little hooded roof. Morris doesn’t do this, but the hooded fireplaces in Dahlander’s houses seem to be transitional between late Victorian and Arts and Crafts, often with large square solid glazed tiles and ornate ironwork on the fireplace opening and surround. Cool stuff, but a lot to dust.

Monstrose, any idea what year or decade the hooded fireplace is from? 1890s also?

(We have a nearly identical fireplace, minus the hood, that doesn’t match the other fireplaces in our circa 1893 house.)

Great article. I’ve never seen a hooded fireplace like you show in the photos. Neat. Seems a little cruel to put the trunk room on the top floor, but maybe that was where they were loaded and unloaded–near the bedrooms.

rf, I know which lot you mean, that’s my old block. There was a house there at one time, but I don’t know the story behind what was there. The house has been gone for a very long time, gone before I moved there in ’83.

It’s still a beautiful block.

MM, is there a similar story about the empty lot we once talked about, on the north side of Jefferson between Marcy and Tompkins? The one with the driveway and dog?