How Brooklyn's First Free Library Became the Brooklyn Museum

It grew from a small library to a massive and wide-ranging educational institution before focusing on art.

The Brooklyn Museum in 2021. Photo by Susan De Vries

Many of the great museums of the world started out as the private collections of very wealthy people. New York’s Guggenheim, the Frick, the Morgan Library and London’s Tate Modern are examples, to name just a few. Manhattan’s Metropolitan Museum of Art was the brainchild of a group of wealthy Americans meeting in Paris in 1866. They wanted to establish “a national institution and gallery of art.” They came back to New York and incorporated in 1870. The Met was always meant to be a public museum and was first housed in a building on 5th Avenue near 54th Street. Brooklyn’s great museum had a very different origin. The Brooklyn Museum began as a small library.

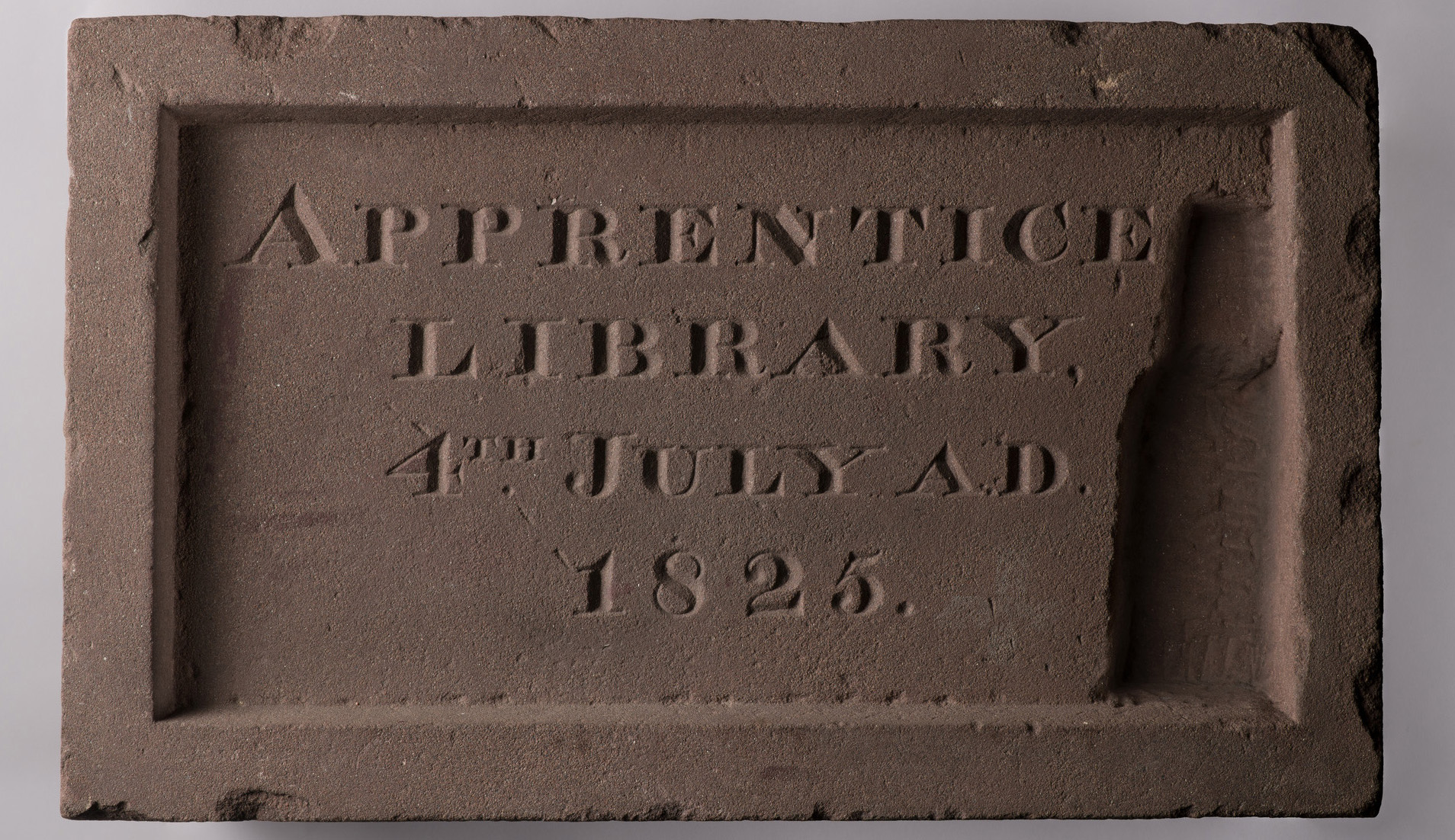

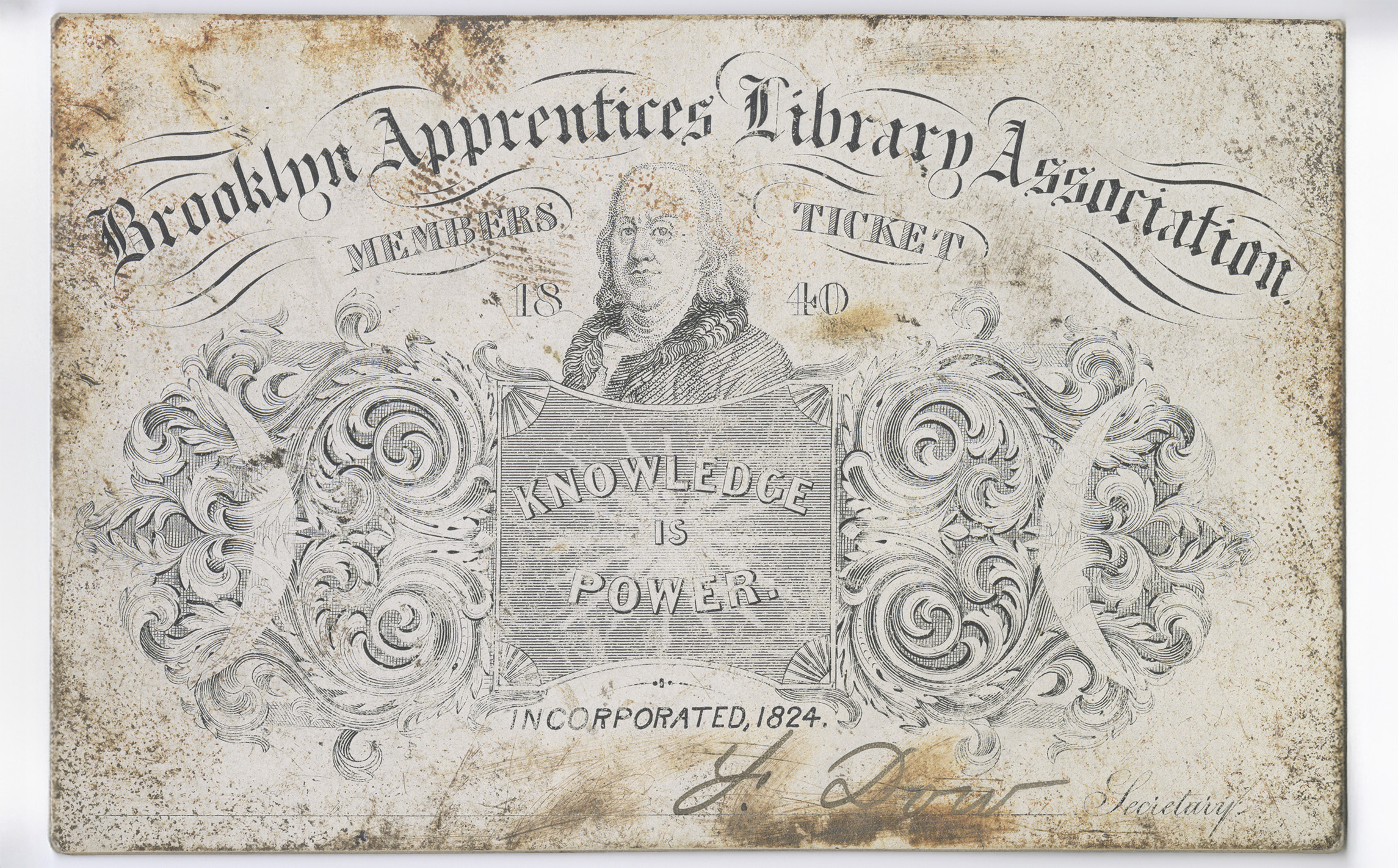

The Apprentices’ Library was established on November 24, 1824. It was the first free library in Brooklyn. The library found a permanent home on the corner of Cranberry and Henry streets. The cornerstone for the three-story frame building was laid with much ceremony and pomp by the famous French general and hero of the Revolutionary War, the Marquis de Lafayette himself, in 1825.

The idea and the money for the library came from a small group that included Augustus Graham. He and his brother John owned a very lucrative business manufacturing white lead, a naturally occurring salt primarily used in paint and cosmetics. (Not anymore, for obvious reasons.) Both brothers were very generous with their money. Augustus was also the primary donor for Brooklyn Hospital, the city’s first, and John founded the Graham Home for Old Ladies in Clinton Hill.

Augustus and others realized that the general workforce of the day didn’t have funds to buy books or other learning materials, all of which could propel them into higher paying work. Many of Augustus’ factory workers had little or no formal education. The founding documents of the library state that it would be a “repository of books, maps, pictures, drawing apparatus, models of machinery, tools and implements, for enlarging the knowledge in literature, science, and art, and thereby improving the condition of mechanics, manufacturers, artisans, and others.”

The library had classes in the evening open to anyone to teach reading, writing, grammar, mathematics, and specialized skills in architectural and mechanical drawing, bookkeeping, landscaping, and more. A small amount of tuition was required, but students could pay on an installment plan. The library was so successful that by 1841 it needed a much larger home.

The Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences

It moved into the Brooklyn Lyceum on Washington and Concord streets, sharing space with the Lyceum’s own subscription library, and was home to several other small collections and organizations. The two merged in 1843 and became the Brooklyn Institute.

In 1845 Augustus Graham bought the building. When he died in 1851, his will included funding for the Institute so that it could expand and open a natural history department and a school of design. His only stipulation was that every year a free lecture must be given on the “Power, Wisdom, and Goodness of God,” which the Institute honored for many years. He also set up a fund to purchase works from contemporary artists, the first of its kind, enabling the Institute to build a permanent collection. The organization continued to grow, and by 1853 had an arts department, as well as literary, dance, and mechanical departments.

By 1867, the Institute included a new extension with a library and reading room on the ground floor along with other general-purpose rooms for meetings and classes. The second floor was taken up by a lecture hall with a music gallery, and the third floor had a picture gallery, artist studios, and other classrooms. Tall exhibit glass cases in the basement housed various artifacts and natural history collections.

A large part of the Institute’s activities surrounded lecture series. Going to a lecture and learning about a myriad of topics was one of the era’s most popular evenings out. Most people of middle class means never travelled to exotic lands, would never explore sea life, or learn about artists from the Florentine Renaissance. Lectures were not only educational, they were also recreational and aspirational. Knowledge and culture were offered at a reasonable price.

By the time the 1880s rolled in, the Institute was well known for its lectures. Most had moved outside of the building years before and were being held in theaters, concert and Masonic halls, churches, and anywhere else one could seat a decent-sized audience. The organization’s number of departments grew as well, and lecture topics in 1888 included “The Arctic,” “Volcanoes,” “The Chemistry of Food,” “Glaciers of Alaska and the Age of Ice,” “the World of the Mapmaker in 1450,” “Mountains,” “Yellowstone Park,” “Human Evolution,” “Acoustics of the Human Voice,” “Florentine Renaissance in Art,” “Origin and Development of Greek Architecture,” and an “Exhibit of the Department of Microscopy” featuring 60 microscopes for attendees to take turns using.

The Institute had become more of a university than an exhibit hall. It now had formal departments of botany, chemistry, mineralogy, entomology, geology, natural history, microscopy, physics, zoology, music, art, and engineering. On June 27, 1881, a fire broke out in one of the artist studios on the top floor. Soon all four studios were consumed. Considering the paper, canvas and wood, oil paints, and other chemicals present, the Institute was fortunate the fire didn’t take the entire building. It spread to the floor below that now housed the library and lecture hall. The librarian called it in, and fire engines from three local firehouses rushed to the scene. For a while it looked as if the building would be lost, but the firemen were able to contain it on the top floor.

There was a lot of water and smoke damage and the Institute lost some of its books and exhibits. One of the casualties was the painting called “Winter Scene, or Brooklyn in 1820” by Francis Guy, an invaluable 1819-1820 painting showing the village of Brooklyn, along with the homes and businesses of some of Brooklyn’s oldest families. The large painting had a place of honor in the lecture hall, directly beneath the artists’ studios. It was damaged in the fire and about two feet of the left side were destroyed. What we see today is the undamaged part of the canvas, a wonderful depiction of everyday life in early Brooklyn. As it happened, one of the houses in the ruined section was that of Augustus Graham.

The fire and damage to the structure as well as artwork, books, and exhibits, gave new urgency to constructing a larger building for the organization. By 1888, the Brooklyn Eagle noted, the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge had taken the Institute from a rather overlooked area of town into the center of everything, as the entrance to the bridge was now practically by its door. In 1889, departments of architecture, political and economic science, photography, astronomy, and archeology were established. They were joined in 1890 by philology (speech study), geography, electricity, mathematics, painting, bacteriology, and psychology. All these groups and more had research materials, exhibits, collections, artifacts, dedicated literary materials, and other objects. Some needed lab space; all needed lecture and office space. The institution now had 27 departments, all vying for space.

A committee of Brooklyn’s elite was created in 1889 to oversee the building of a new museum for the City of Brooklyn. The newly formed Department of Architecture was recruited to hold a competition for the design of this marvelous edifice. The site had already been chosen – city owned land near Grand Army Plaza on Eastern Parkway. This was land originally obtained for the first plan for Prospect Park, which crossed Flatbush avenue and included the Prospect Reservoir. When the final design for the park put the green space on the opposite side of Flatbush Avenue, this portion of acreage, called the Eastern Lands, was saved. The museum would be just to the east of the reservoir, with a new central library planned for the triangle created by the intersection of Eastern Parkway and Flatbush Avenue.

Funding for the new Institute of Arts and Sciences came from the city’s sale of unused parkland, now making up much of Prospect Heights, plus bonds authorized by the state, as well as subscriptions and donations from the public. The building committee drew up a lengthy list of must-haves and specifications for the new building, including placement, size, shape, and materials. They then announced the competition in 1893, inviting 70 architects and firms to submit their best designs. Most of the contestants were from Brooklyn and Manhattan and included the pantheon of Brooklyn’s most prolific and popular architects. The Department of Architecture chose their president, George L. Morse, as a judge, as well as Professor A.D.F. Hamlin of Columbia College, and Robert S. Peabody, a prominent Boston architect.

Each contestant submitted numbered plans and models, so it was conceivable that even the humblest journeyman architect could compete against some of the day’s biggest names. In the end, the choice was between designs by Brooklyn’s own Parfitt Brothers; Carrere and Hastings; McKim, Mead & White; and the firm of Cady, Berg & See, who designed Manhattan’s Museum of Natural History. The prize went to the designs of Charles Follen McKim of McKim, Mead & White. The new museum would be a massive limestone and marble edifice, in the popular White City and City Beautiful Classical style and would be the equal to any museum in America. Construction began in 1895 with an elaborate cornerstone-laying ceremony.

One of the criteria for the overall design was that it had to be square, with a large center courtyard. The design also had to be such that it could be built in sections, as money allowed. McKim’s design fit the bill perfectly, with each side of the square a separate entity. The entrance faced Eastern Parkway and was the first section built. Had the full design for the museum been completed, what we see today would have been duplicated on all four sides, creating a massive structure, one of the largest in the country. The entire project was budgeted for $3 million, which would be close to $115 million today.

While they looked forward to the first phase’s completion, the 27 departments and their stuff had to go somewhere. A great deal of it went into storage, and many of the private collections that were donated to the Institute went back to their donors for safekeeping. Most of the labs for the different science departments had already moved off site after the fire, and the YMCA on Fulton Street and Gallatin Place became the main lecture hall. Packer Collegiate offered space to the Physics Department, and a large estate was rented in Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island for the biology, ecology, and natural sciences departments.

In 1893, the Institute leased the Spanish Adams Mansion on the corner of Prospect Place and Brooklyn Avenue, at the edge of Bedford Park. There, the departments of geography, zoology, mineralogy, botany, and geology were relocated and exhibitions set up in various rooms. In 1895, the library was moved from storage to this location, and reopened to the public. The Spanish Adams Mansion was used as the outpost of the Institute until 1899, when it was repurposed as the Children’s Museum and Library, the first children’s museum in the country. The park was later renamed Brower Park, and the Brooklyn Children’s Museum is still there in Crown Heights North.

The Brooklyn Museum

The first section of the new Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Science was dedicated on October 3, 1897. The ceremony was held in what would become the spacious sculpture room. In attendance were the mayor and parks commissioner, the Brooklyn Board of Trustees, the president of Harvard, representatives for both Protestant and Catholic faiths, and a representative of the Grand Army of the Republic. In the audience were “many women of prominence in Brooklyn in the educational and social fields,” reported the New York Times.

Everyone associated with the project was quite pleased with the results, even though the building was still under construction at the dedication. They looked forward to the construction of the second section, to be followed by the remaining third and fourth sides, completing the square. Had the entire project been completed, all 27 departments would have ample space for display, research, teaching, and exhibitions. The Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences would be a world class self-contained center of learning and the arts unlike any other. It was almost unimaginable.

But several roadblocks and events thwarted the plans. Money, of course, was always a concern. But perhaps more important, January 1, 1898 happened, when Brooklyn ceased being an independent city and became part of Greater New York. The rivalry between Brooklyn and Manhattan began when the Dutch settled both sides of the East River. By the latter half of the 19th century, Brooklyn, with its huge manufacturing base, had grown into the third largest city in America. The unwritten contest between cities grew. Each side tried to do one better, especially when it came to public institutions and places like parks, civic buildings, and museums.

Now that Brooklyn was simply a borough, city fathers decided that Brooklyn didn’t need to have the largest institution of its kind. The city of New York was not going to spend the kind of money that the City of Brooklyn would have for a borough museum. The bean counters weren’t the only reason, but without the money to expand the Institute, it was decided that what was built was going to be it.

It was still pretty impressive, and it wasn’t until the 1920s and ‘30s that the empty land across Eastern Parkway and further east filled with apartment buildings and schools. As the 20th century progressed, the museum began paying more attention to the arts and slowly phased out the sciences, the architecture department, and other disciplines. The Brooklyn Botanic Garden grew next door, and the reservoir was filled in, making room for the new Central Library in the late 1930s.

Even though the Institute would not be able to add more wings, it still had other important institutions under its umbrella. The Children’s Museum, the Botanic Gardens, and even the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) would not become separate entities until the 1960s and ‘70s. As for the name, the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Science became the Brooklyn Museum in 1916.

What happened to all the other departments? They were phased out or absorbed by other institutions and organizations. The biology department and its laboratory became part of the Long Island Biological Association, which is now the Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory, a world-renowned scientific center. The other natural science departments held on until around 1935, when their collections were deaccessioned. They had probably been relegated to a room in the attic somewhere as the museum expanded its arts department and permanent collections. The Brooklyn Public Library took many of the Institute’s books, and societies such as the Brooklyn branch of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), took over many of the functions of the architecture department. Many of its members were in both organizations already.

The Brooklyn Museum has been a prominent feature in Brooklyn life ever since. Local newspapers kept the public informed of new exhibits and acquisitions. The organization could often be very forward thinking, and sometimes its actions were controversial. In 1913, the museum turned down a painting called “To the Highest Bidder,” a depiction of a slave mother and child on the auction block. The museum said that the painting kept alive memories that “had better be forgotten.”

The artist, Harry Roseland, told the New York Times that he did not see what the objections to the painting were. In a separate editorial, the paper agreed with the decision and said that “Mr. Roseland’s painting, if it is artistically good, will survive, and it is not needful to the painter’s fame that it should be preserved in a public institution.”

Another example of progressive thought took place in 1945, when the museum hosted a traveling exhibition called “The Negro Artist Comes of Age,” which included contemporary art from many of the leading African American artists of the day, including Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, and sculptor Selma Burke. The show was well attended and reviewed positively. Brooklyn has always been more attuned to a wider demographic.

Like all museums, the Brooklyn Museum works mightily to attract visitors and cultivate new members who will return often. It has some very important works in its permanent collection, which includes collections of art from all over the world dating from antiquity onwards, and much more. There were so many changes, challenges, disappointments, and exhilarations in the 20th and 21st century to add to this tale, but that needs to be another story altogether. You can’t be a true Brooklynite and not visit the Brooklyn Museum. It’s a hard-won treasure, inside and out, and the pride of Brooklyn.

Related Stories

- Take an Early 20th Century Tour of the Brooklyn Museum (Photos)

- City Pride: The Making of Brooklyn Borough Hall

- How Charles Pratt’s Morris Building Company Beautified Brooklyn

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment