A Library for All: The Story of Brooklyn’s Central Library, Decades in the Making

No matter if you are in a large city or a small town, the public library has always been a place to discover new worlds.

Photo by Susan De Vries, 2022

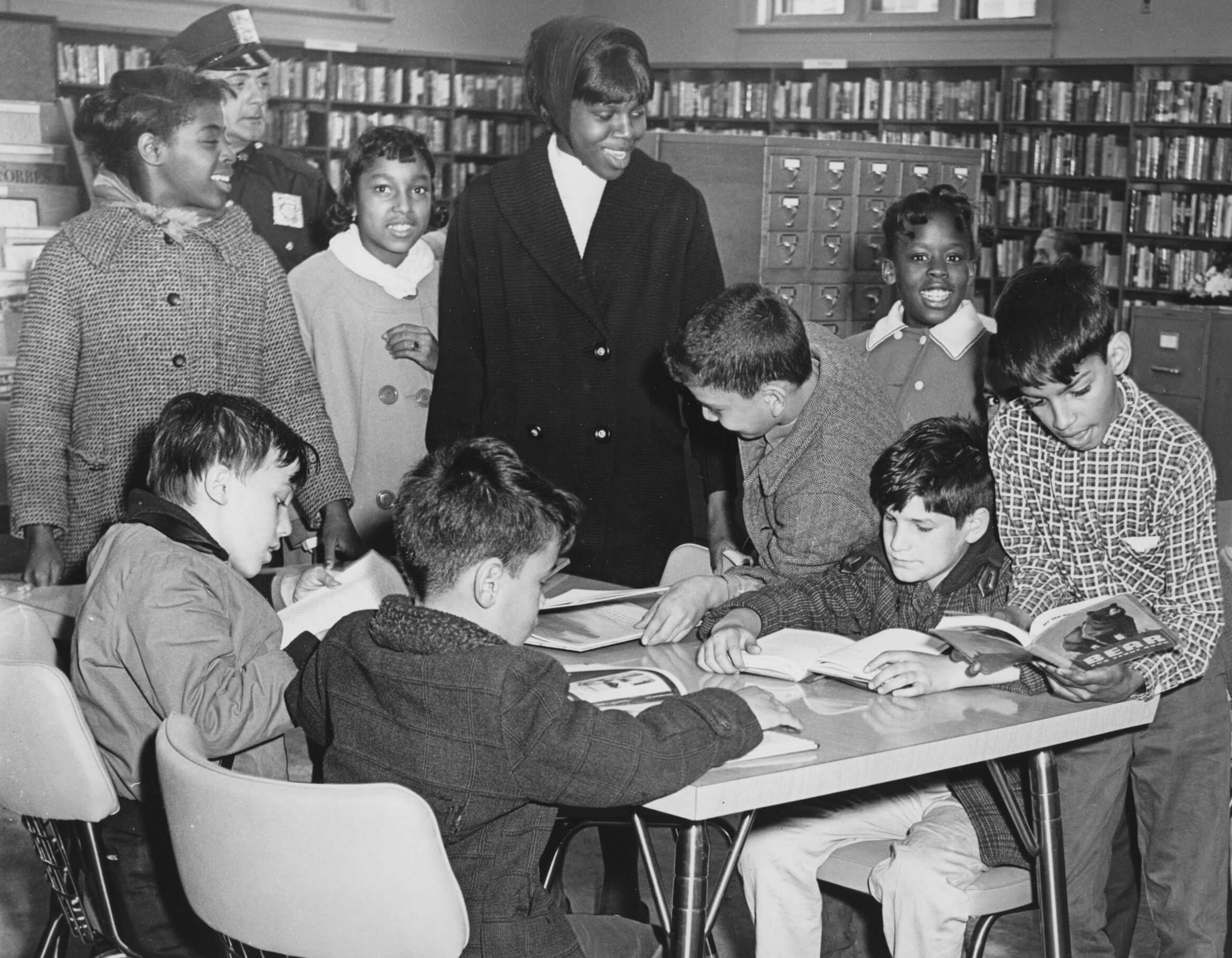

It would be hard to imagine growing up without a public library. No matter if you are in a large city or a small town, the public library has always been a place to discover new worlds. Within the library walls can be found the world we know as well as new worlds of imagination, talent, and creativity. Libraries are places where people can find help and services, be it free computer and Internet access, employment services, or general and historical information. Even if we are infrequent users of our libraries, we know they are there, thanks to generations of people who have deemed libraries necessary to the health and growth of the community.

But it was not always so. Our public library system in Brooklyn is celebrating its 125th birthday this year. Collections of books and reading materials have been gathered for use much longer than that in Brooklyn, but they were not free and available to all.

The Apprentice Library, founded in 1824, was established by manufacturer and philanthropist Augustus Graham. One of Brooklyn’s first libraries, it offered male subscribers access to books, maps, tools, and other instruments that would aid in the self-education of a new generation of workers. The library’s first permanent home was on the corner of Cranberry and Henry Street, its cornerstone laid by General Lafayette himself. As the organization grew, it became the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, which became the Brooklyn Museum.

The Brooklyn Athenaeum was founded in 1852 by prominent Brooklyn Heights residents. Young men were invited to the library in the hall on Atlantic Avenue to read all kinds of literature. In 1857, the Brooklyn Mercantile Library Association was founded to allow young men access to a private collection of business, commercial, scientific and mathematical texts.

Pratt Institute debuted the first free library open to all, male and female, with no restrictions of race. It also established the first library for children. Charles Pratt himself was self-educated through libraries and wanted to offer that opportunity to as many as he could. His Pratt Institute Library opened in 1888.

But so much more was needed. The Brooklyn Public Library system was designed to bring libraries to all corners of the city and to all readers. The collections of the Athenaeum and the Mercantile Library were combined, ready for the creation of the Brooklyn Public Library in 1892. When Brooklyn became a part of Greater New York, in 1898, the library was one of the few things that remained independent.

Brooklyn’s First Central Library

In 1897, the Bedford Library opened as the Brooklyn Public Library’s first branch. Bedford was one of the fastest growing upscale neighborhoods of its day, and had an empty school building, formerly P.S. 3, on Bedford Avenue near Lafayette, close to public transportation and perfect for the first Bedford Library.

In 1899, the library moved to the Brevoort mansion near Atlantic and Bedford. This huge mansion, today long gone, had been built in 1891 for members of the Brevoort family, related by marriage to the Lefferts family. The last Brevoort died before the mansion was finished, and the house was offered for sale.

The parlor floor was home to reading rooms and the stacks, with the library’s administration and other operational offices and storerooms on the upper floors. It was thought that this new building, also conveniently near several modes of public transportation, would suffice for quite a while. But the library outgrew the mansion and moved again in 1902 to Avon Hall, a concert hall, back again on Bedford Avenue, near Halsey Street. The administration offices stayed in the mansion. But big changes were afoot.

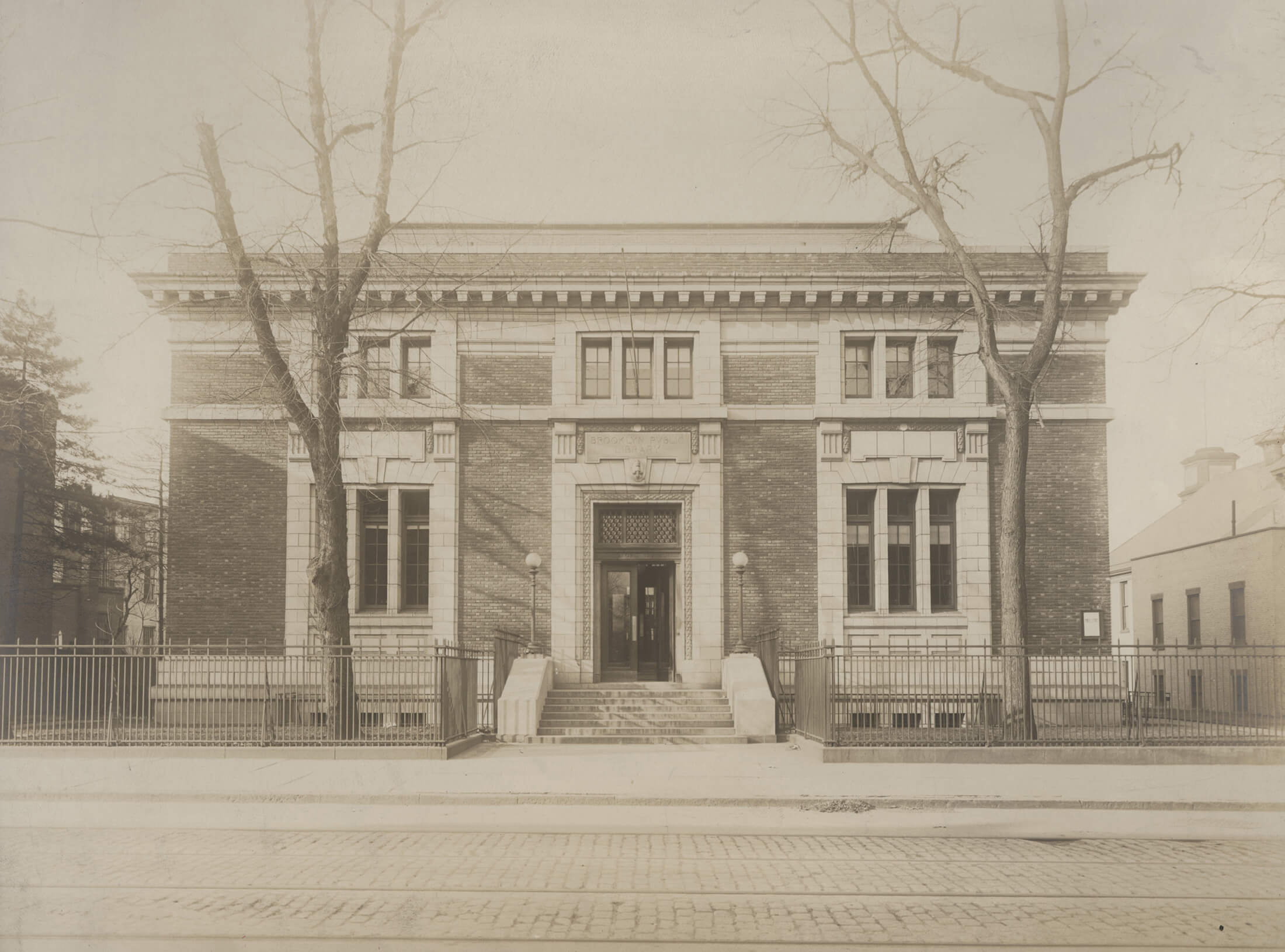

Between 1901 and 1923, the Brooklyn Public Library was a recipient of industrialist Andrew Carnegie’s largesse. Like Charles Pratt, Carnegie was primarily self-taught, thanks to a wealthy patron who allowed the young Andrew access to his private library. Carnegie money helped to fund the building of 21 branch libraries throughout the borough, as well as 46 more in the rest of New York City. One of these was a new building for the Bedford Library. Designed by Lord & Hewlett and completed in 1905, the branch is on Franklin Avenue at the intersection of Hancock Street. The new Bedford Library was never intended to be the Central Library. Carnegie money was earmarked for neighborhood branch libraries only. A Central Library had to be funded by other means. The new Central Library would hold offices as well as special collections and services that the smaller libraries could not house.

The Long Road to the New Central Library

The Carnegie money was managed by a library steering committee that included an architectural oversight committee. Here in Brooklyn, the BPL’s architecture committee was not above some self-dealing, and several members gave themselves commissions. The secretary of this commission was architect Raymond F. Almirall, a Brooklyn native, and a fine architect in his own right, a graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

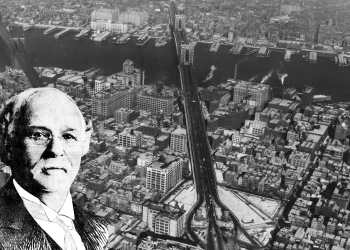

He received contracts for three Carnegie libraries: the Pacific, Park Slope and Eastern Parkway branches. In 1908, Almirall was chosen to design the new Central Library, which would be located in Institute Park, a piece of undeveloped land at the edge of Grand Army Plaza. The site already belonged to the city, left over from land acquired, but not used, in the creation of Prospect Park. Reserved for civic use, at the time it was home to the Mount Prospect Reservoir and the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences.

Almirall designed a classic Beaux-Arts building in marble, with a large central dome and entrance at the apex of the building, with colonnades running along both Eastern Parkway and Flatbush Avenue. It would complement McKim, Mead & White’s museum just up the street, as well as the arch in Grand Army Plaza and the classical entrance to Prospect Park.

He planned the latest accoutrements of library science, with reading rooms, classrooms, music rooms, an auditorium, a children’s library, research and rare book rooms, lunch rooms, miles of stacks, and an underground garage with book elevators and conveyor belts for transporting books. The back sorting rooms would have tracks for carts to run along for transporting books. Rooms dedicated to cataloging and restoration and repair were mapped. The new library would also have a first aid station, a newspaper room, and telephone and stenographer’s rooms. The cost was estimated to be $4.81 million.

Ground was broken for the library in 1912. By 1913, the foundation had been dug out, and part of the west wall along Flatbush Avenue had been built. Then the money ran out, and work stopped cold. It would not begin again for another 30 years. Almirall would never touch his Central Library again.

The city’s library funding became mired in politics, budget cuts, and bureaucratic ineptitude. Meanwhile, with the addition of new branch libraries, the offices in the Brevoort mansion were bursting at the seams. In 1925, the organization voted to move their offices to 280 Washington Avenue in Clinton Hill. Even as they moved in, they knew it was too small, but construction of the Central Library had been promised. In 1930, the library rented the entire seventeenth, and part of the eighteenth floor of the new Williamsburg Savings Bank Tower in Fort Greene as their temporary headquarters.

The Completion of the Central Library

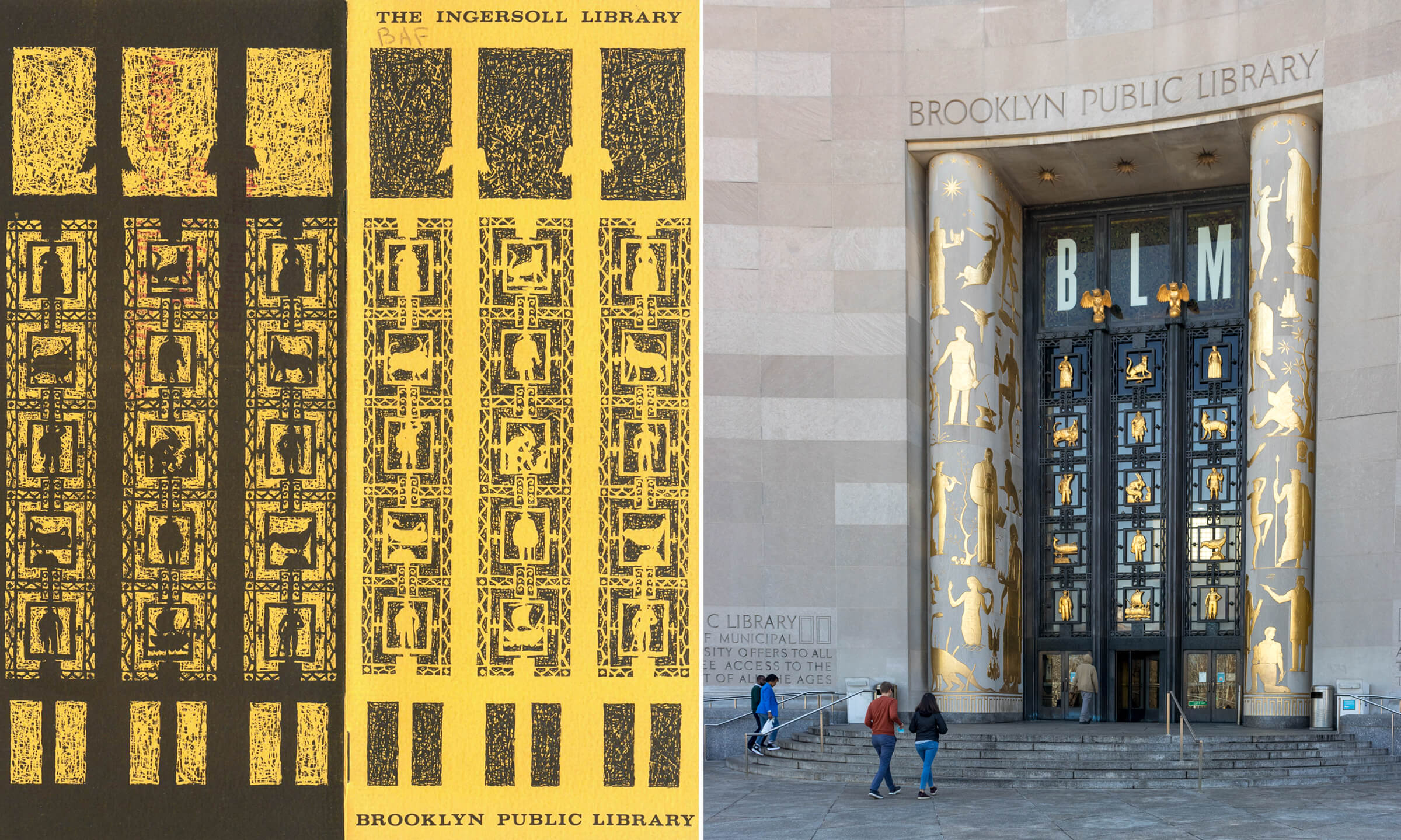

By the 1930s, Beaux-Arts architecture was out of fashion and Art Deco and Modernism were in. With the Flatbush wall and the building’s footprint already established, new project architects Alfred M. Githens and Francis Keally had to work within Almirall’s original configuration. They designed a sleek Modern Classical building. The Flatbush Avenue wall was stripped of its marble sheathing and worked into the new design. The entrance was redesigned to curve in and welcome visitors.

The ornamentation reflects the Art Deco/Moderne love of design in relief. The reliefs on either side of the doors were designed by Carl Paul Jennewein, and the bronze screen is by Thomas Hudson Jones. Quotations about seeking knowledge invite the reader into the library.

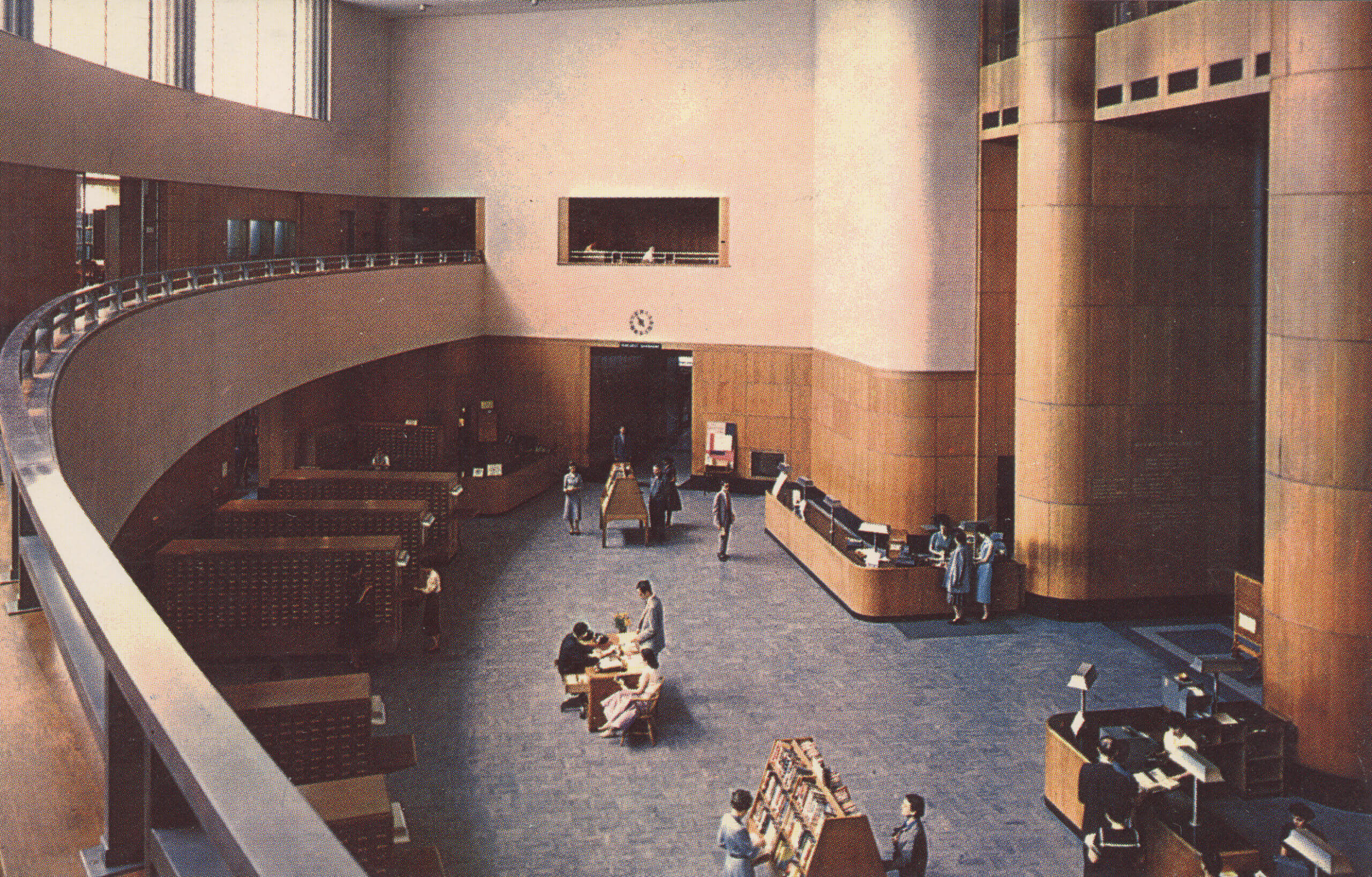

Many of the amenities and features that Raymond Almirall envisioned for his Central Library were realized. When the library opened with great fanfare in 1941, visitors entered one of the most impressive Modernist spaces in New York City. The library has been well loved and well used ever since. It has been able to change with the times and with new technology. It is the community resource that its founders wanted it to be.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- A Whimsical William Tubby Design for Brownsville’s Bastion of Knowledge, the Stone Avenue Library

- Brooklyn Heights Library Opens in Sleek New Digs at Base of Condo Tower

- Living the Good Life on Eastern Parkway

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment