Making a Life in Brooklyn: Carroll Gardens Brownstoners in the 1960s

It was a time in Brooklyn when two schoolteachers with adventurous spirits and a willingness to get their hands dirty could cobble together enough money to buy their own slice of the borough.

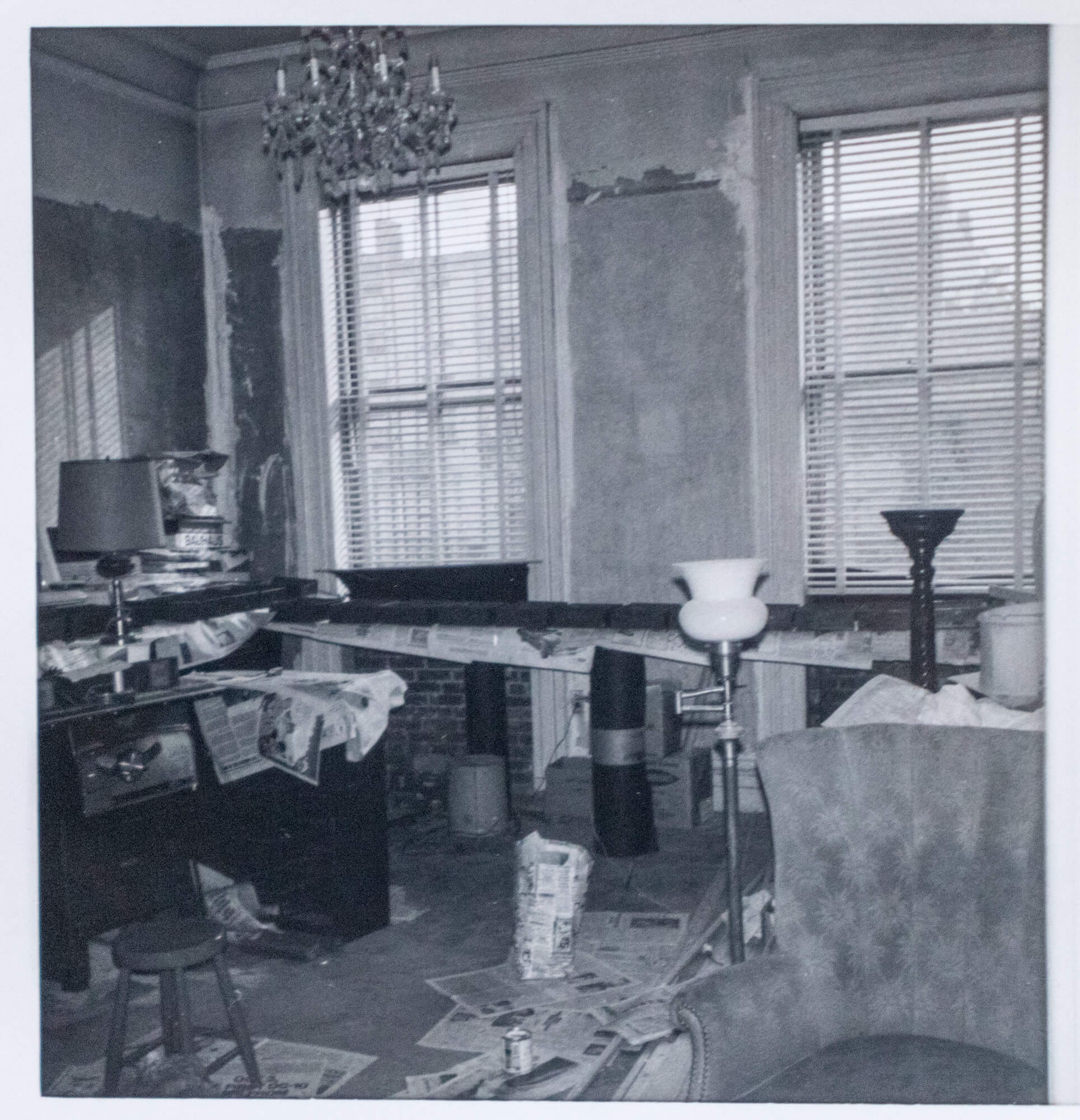

Jane Rinden at work on the parlor floor

It was a time in Brooklyn when two schoolteachers with adventurous spirits and a willingness to get their hands dirty could cobble together enough money to buy their own slice of the borough. In 1968, Thor and Jane Rinden bought an 1870 brownstone at 12 2nd Place in Carroll Gardens for $28,000 and began a five-year process of restoration and transformation.

Both were teaching at the time. Jane was an English teacher at Packer Collegiate Institute and Thor an art teacher at Halsey Junior High. Thor would later leave teaching to devote himself to painting full time.

The couple weren’t alone in their home-ownership journey, they were joining other brownstoners who were finding the 19th century housing stock of Brooklyn alluring and inexpensive. While fights over urban renewal and slum clearance plans were raging in the city, people were rejecting suburbia and reclaiming the historic architecture and neighborhoods of the borough.

Jane and Thor celebrated the completion of their major overhaul in 1973. Over the subsequent decades they built a life in the house that revolved around art, travel, books and community. Thor died in 2009 and Jane this August, online records show.

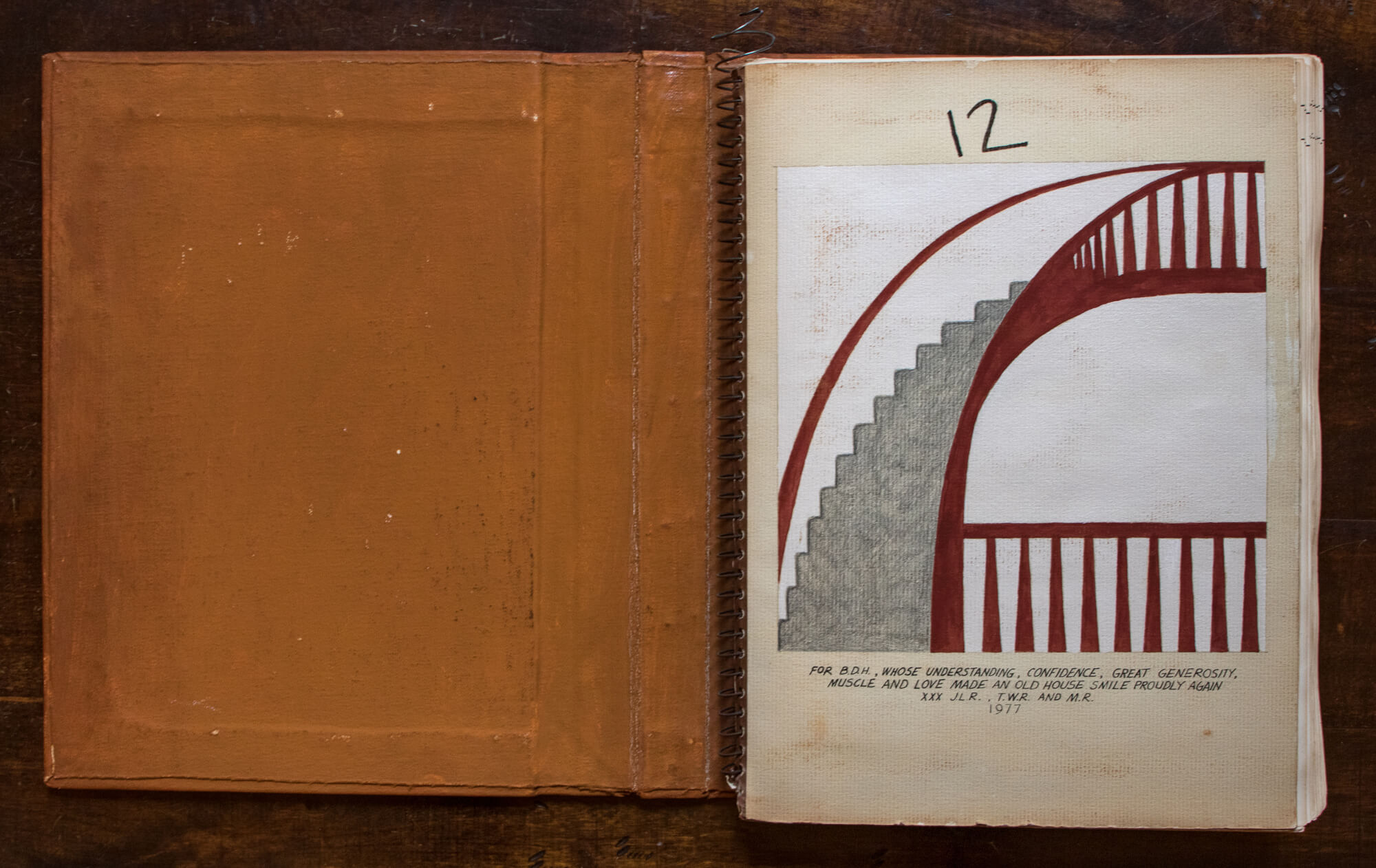

They both left remarkably detailed records of their home-improvement adventures. In 1977, Thor compiled a scrapbook filled with photographs and captions documenting almost every step of the work. After Thor’s death, Jane compiled her writings into a memoir about their life together, including a chapter entitled “Brooklyn Based” about her memories of buying and restoring the house on 2nd Place.

Thor’s scrapbook, such a rich source of information on the brownstone movement of the 1960s and 1970s, will fortunately be preserved for future generations. The executor of the estate told Brownstoner she plans to donate the book to the Brooklyn Collection of the Brooklyn Public Library.

Below are edited excerpts from the “Brooklyn Based” chapter in Jane’s memoir, along with photographs and captions from Thor’s scrapbook. Both are reprinted here with permission from their estate. In Jane’s words:

Our decision to buy a house in Brooklyn was made in early July, and for the rest of the summer we walked up and down neighborhood streets in Cobble Hill and Carroll Gardens, admiring the residential blocks of 19th century brownstone houses. In the warm evenings when people would be sitting on their stoops, we would linger under the sycamores and talk, asking them if they knew of any houses for sale.

On September 11, Carol [Salguero] called to say a house on her block had just gone on the market that day. We couldn’t believe it. Second Place was not only a prime Carroll Gardens street, just three blocks long, with almost completely intact four-story brownstones, but also, those brownstones sat far back, looking out on verdant front gardens, a rarity in the city. As soon as we saw it, we knew it was the house we had been waiting for.

At first my parents had driven in to see every house with us, but they quickly grew discouraged when they saw the amount of work to be done on them all. Now we convinced them that they must return, and on September 13 they came in. With Carol’s assistance, we had strategically arranged that we take them first to her house, so they could see what a refurbished brownstone looked like. They were charmed, not only by her house and young children, but by her canned jars of fruit and vegetables lined at the top of the kitchen cupboards. They seemed to prove that one could live a normal life in the city after all.

Walking down the block, we crossed our fingers. Our house still had big cabbage-rose wallpaper in the parlor and linoleum on the floors, but now my parents knew that there was parquet under that linoleum, and the sun pouring in the kitchen window guaranteed we could have a sink overlooking the back garden. The graciousness of this 17-foot-wide four-story brownstone with a center circular staircase ascending to a skylight had won all our hearts. We made an offer and asked for first refusal. The four of us drove to Metuchen that Friday afternoon, chattering nonstop about the possibilities. And we bought the house over the telephone that night.

Our dual teaching salaries allowed us to buy a Brooklyn brownstone in 1968. When we went to get a mortgage at our bank, however, we learned that our neighborhood was redlined, which meant banks denied mortgages in areas considered not worth their risk of investing. And yet, largely Italian Carroll Gardens had homeowners who lived in their houses, rather than absentee landlords. A stable community, its colorful traditions were old world and well entrenched, such as the annual Good Friday parade at dusk with its float bearing the Virgin Mary moving up and down our narrow streets to the local parish church, followed by a brass band playing mournful music; it was Cavalleria Rusticana come to life.

We thought our neighborhood had great character and potential but, obviously, imagination and foresight were not considered in a bank’s decisions. (There must have been many bankers, down the line, who eschewed their conservatism after our Carroll Gardens garnered a reputation for being one of the best places to live in Brooklyn.) Once again my parents came to the rescue. They offered us a mortgage so our dream could come true.

Not only did our house have a front and back yard, that circular staircase with a room in front and behind it on each floor, original ceiling moldings, parquet flooring, marble fireplaces, and three bathrooms. It also had old-fashioned plumbing, loose plaster, a leaking roof, ill-fitting windows, little insulation and a northern exposure, inadequate electricity, sloping floors, a non-working stove, and a mountain of junk in the backyard.

The first part of that list was what we described in letters to our friends, and when they came to visit, we couldn’t understand their lack of enthusiasm. Not until we began work. The electricians came first, to rewire, adding several hundred holes to plaster walls and ceilings, but these were nothing compared to the white powder that attached itself to everything for months afterward. We would have to dust ourselves off each time we left the house in order to be even somewhat presentable to the outside world.

Being very methodical, once the bare, dangling 25-watt bulbs we had inherited were exchanged for a somewhat softer and definitely brighter effect, we sat down one night and listed all the other messy jobs that must follow before we could consider any form of decoration. (At this point we did not realize that “all” was an unknown quantity, that each job would uncover others we had not dreamed about, and oh, the money.) Meanwhile our new next-door neighbors were postponing their major renovations and simply painting and doing general cosmetic work.

Needless to say, morale in our house was not very high. It was depressing to view their innovative design for a child’s bedroom featured in a New York Times article on brownstoning while our chances for innovation were still tucked behind walls or under floors, and would be for years. Still, we knew we were going about our renovation the right way. And our next project would be the kitchen.

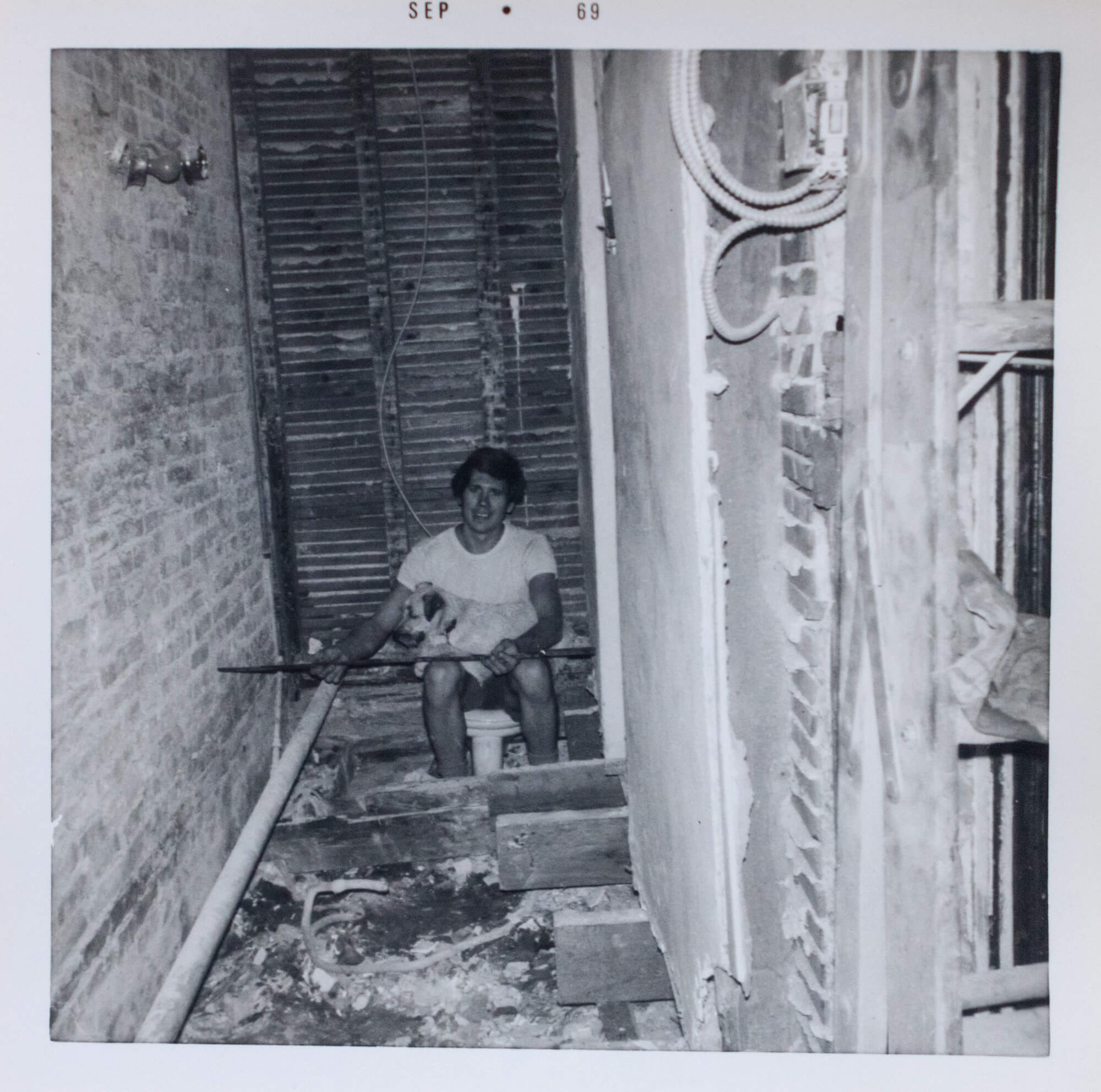

Unfortunately, the basement floor, where the kitchen, dining room and a bath were located, was caving in. Having no cellar, we concluded that the beams must be rotten and would have to be replaced. And so they were, we found, when we ripped up the floor. But not only that — our connection to the sewer from the roof was gone, so that when it rained, the 2-foot-high area under the kitchen flooded. And our bathroom plumbing turned out to have been Scotch-taped together and needed replacement. And did we have termites? (Fortunately not.) Plus, we had an immense amount of dirt that had seeped under the house throughout the years and would have to be removed to regain our airspace. And part of a brick wall and a chimney to be rebuilt for the furnace flue.

Demolition, construction, bricklaying — except for the plumbing, for which we hired a licensed man — our first summer in our house was cut out for us. There was no time for gardening. Or for vacationing. Thought of trips or even occasional days spent away from the house soon became a luxury we could not psychologically afford, always resulting in guilt feelings about what we could have accomplished had we worked instead.

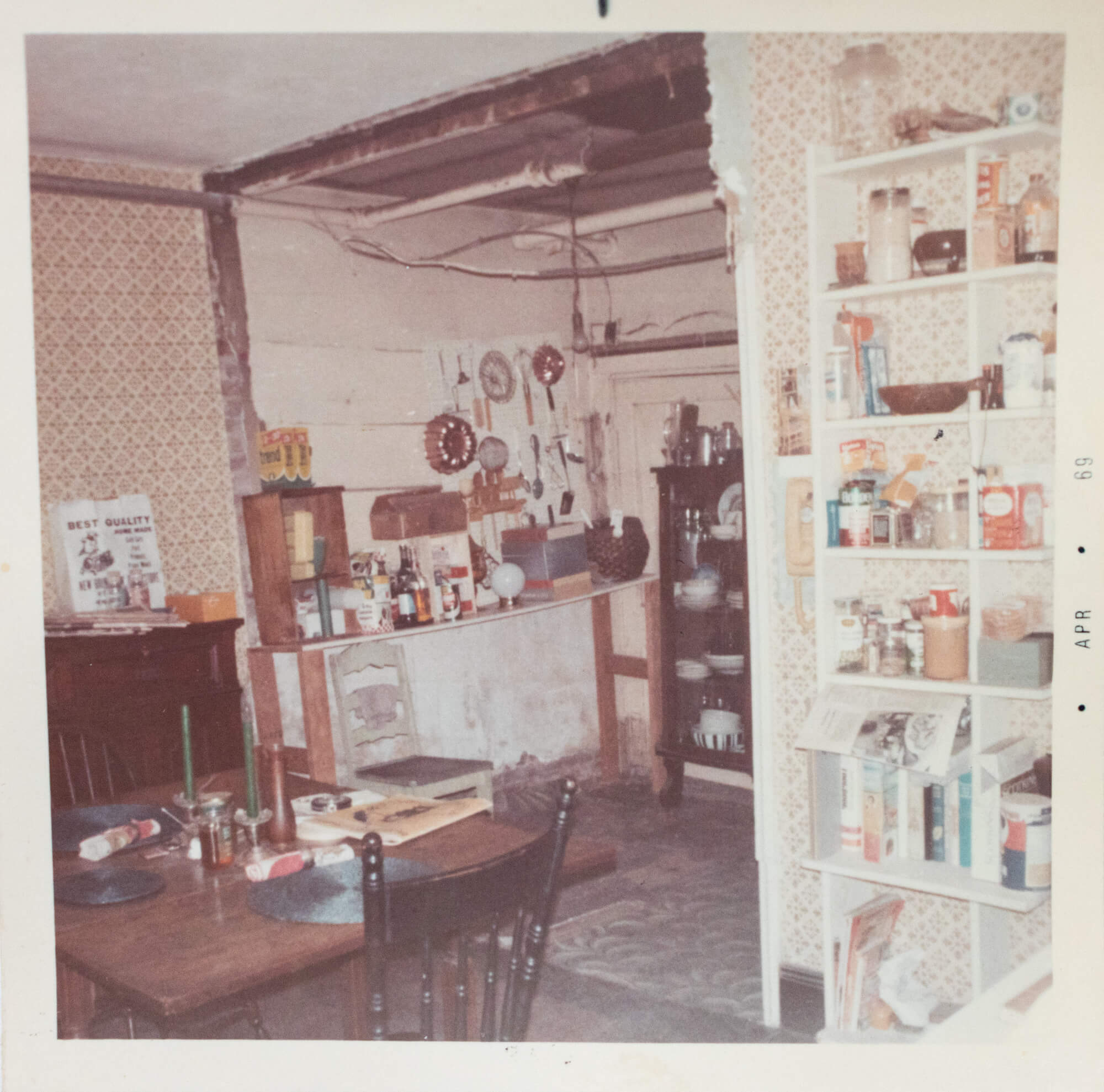

It was at this time that we started to live off a hot plate and an electric frying pan. The living room became our kitchen, its ornate marble fireplace our pantry, and for the next year and a half we went downstairs to the refrigerator and upstairs to get water. (How I dreaded making ice cubes!) With three flights to negotiate for every meal, I learned quickly to plan ahead. Dishes were washed best in the bathtub. This was not our favorite period of renovation.

We might not have taken quite so long to finish our kitchen if I hadn’t noticed the following spring, on my walk home from Packer, a building being demolished. Over the winter we had chopped up, sorted and tied, and slowly fed our inherited junk yard to the garbage men when we weren’t delivering it directly to the local dump. We had already transplanted some overgrown hedges to the front yard for privacy and now the back was clear, ready for the landscape design we had worked out during the winter to start taking shape.

Inspired by a photograph in the paper of a Charleston garden owned by a bank, Thor had adapted its design to our 17-by-55-foot backyard. To offset the narrowness, a curving brick path led to the back, with garden space on either side and several additional raised brick planting areas.

And here it was planting time . . . With permission, for the next several weeks after school we made trip after trip to the site in order to carry home as many lovely pink bricks as our antiquated station wagon could bear. How its springs held out through those countless trips, not to mention our arms as we hauled them first to the car, then out and to the front porch, and finally through the house to the back, seems rather miraculous.

An attached house offers several disadvantages, including this problem of carrying dirty loads through the house proper. Imagine how to get a truckload of sand through to help our hand-laid serpentine path of bricks settle. The finer points of how we accomplished some of those nasty chores I find I have curiously blocked from my memory. But two months later we had a garden — our first completed room — as well as a fence on one side we had designed and built from crating lumber found abandoned on the Brooklyn docks. Our house had become a recycling center long before ecology was a household word.

In the interim we learned that several brownstoner friends had had fireplaces restored for wood burning — a major job since the flue walls had to be chopped out all the way to the roof so they could be completely relined. With all our fireplaces we decided it would be a bad mistake if a few were not usable on cold snowy evening . . . so the fireplace men moved in for two weeks. Plaster dust was nothing compared to the havoc they wrought. Powdery black soot now descended on us and into us as the flues were opened and the house’s archaic heating system removed from the chimneys. Being away teaching while they worked saved us, though invariably I would come home to find the dinner I had planned eaten, and I discovered chicken bones among storage boxes months later. I soon decided I was happiest when I saw workmen leaving for the last time.

Some workmen, however, were better than others. The men who built and restored our windows for us during the summer were a joy. We barely knew they were there until one day they reported they were finished. We checked the weatherstripping and realized our heating bill would plunge that winter. And it did.

On the other hand, we had to threaten to sue our Formica man before he completed our kitchen counters. By fall we were able to move in appliances and put food on shelves, although several times I found myself on the stairs before I remembered there was a water faucet in the kitchen. But the finishing work of cabinet doors and hand-painted floor I had been working on all summer was left undone because messy jobs were still to follow.

Organization continued to precede convenience in our methodical lives. With another school year beginning, we also took on the task of plastering. Every Saturday through the following February, after doing preparation work during the week, we worked with the plasterer until the house was patched, and in some rooms completely replastered.

By now we were discovering that our old-fashioned bathrooms were impossible to clean and that we really ought to modernize the one on the bedroom floor. We could restore up to a point, but after all, bathrooms themselves had been later additions. So we shut our eyes and out went the bathtub with clawed feet. Three months later we had a new and plastered bathroom, but by then we had temporarily moved our living quarters to the top story so the parlor and bedroom floors could be scraped. Thus, we were not able to enjoy its luxuries for a good while yet.

The floors were our first finishing job. We had so many new pipes and wires in the walls, and even new walls, but nothing really showed. Our garden alone could give us any real sense of accomplishment. Then, suddenly, the dingy linoleum-covered parquet was glowing and beautiful, and we couldn’t wait any longer — we bought paint. (Only after scouring every paint chart in the city, to find the four off-white shades which would blend and yet show off our various moldings.)

Spending our third spring and summer atop a ladder building bookcases and closets, then preparing (an interminable, hideous task) and painting four rooms was a dizzying job, especially with 13-foot ceilings. But what joy to see the gleaming results, to place furniture, to hang plants and pictures. And best of all, to unpack our precious books. Our quality of life was looking up.

Of course, we were cheating; there were still major jobs to be done, but there were times when our spirits needed sustenance. In the next two years the kitchen would be finished, an elaborate tray ceiling built in the dining room to hide all the pipes coming into the house, and the two living room windows restored to their original floor-to-ceiling height of 12 feet, which meant scavenging for weights in some condemned brownstones in Williamsburg, as our window men had told us such large weights were no longer made. Risky business, but we found them.

Perhaps most ambitious was the leveling of our sloping floors in the halls and living room. Over a century the house had settled toward its circular stairwell. Just before we bought it, we had asked a structural engineer to check the house, and he assured us that the three-martini feeling we had when we stood looking up could be remedied. And he was correct — not, however, without more intensive planning and labor. Thor figured out how to rebuild all the stairs and stairwells to even them out after I had removed the parquet floors in halls and much of the parlor, then later replaced them piece by tiny piece.

Through it all my parents helped us physically as well as financially. Depending on what we were working on, they came in on weekends and pitched in like day laborers. Or they would take us out to dinner when we had no stamina left to make our own.

In 1973 we looked back at what we had accomplished. Because we had worked over a period of five years, we never needed a Dumpster. The only money we borrowed was $10,000 dollars from Thor’s parents, and we repaid that within six months. We were justly proud of our house because we had done most of the work ourselves. It had become our first collaborative work of art. And that was due to the fact that Thor could both visualize a problem and solve it by tackling it with his hands. He had taught himself to be one amazing contractor. Who says being an artist is not a useful profession?

[Images and text via the estate of Jane Rinden]

Related Stories

- Spotting Cinderella From the J Train

- Longtime Bed Stuy Resident Claudette Brady Reflects on Preservation and Change

- Another Look at the Evelyn and Everett Ortner House

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment