A Winter Walk Through Calvert Vaux Park

Lovers of New York city parks and architecture may be very familiar with the name of Calvert Vaux, but perhaps not so much the Brooklyn park dedicated to the 19th century designer.

Lovers of New York City parks and architecture may be very familiar with the name of Calvert Vaux, but perhaps not so much the Brooklyn park dedicated to the 19th century designer.

A lauded architect and park maker, Calvert Vaux grew up in and was educated in England but is best known for his work after moving to the U.S. His Brooklyn masterpiece is Prospect Park, designed in partnership with Frederick Law Olmsted. Brownstoner’s Suzanne Spellen did a deep dive into the fascinating life of Vaux in a four-part series.

This green space at Gravesend Bay is the only New York City park named for the designer, not because it was a Vaux creation, but because it is not far from the spot where Vaux died in 1895.

Needing a rest in November 1895, Vaux stayed with his son C. Bower Vaux, who lived on 20th Avenue near Benson Avenue. According to newspaper accounts in the New York Times and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle at the time, Vaux never returned from an afternoon walk on November 20.

While extensive walks were not unusual, his son and daughters became concerned when he had not returned by evening. The New York Times reported that the possibility that he had walked to Prospect Park was considered, but “he had not been seen at the Litchfield mansion, and the park police were instructed to search the park for him.”

He also frequently walked to Gravesend Bay and concerns were immediately raised that he may have fallen into the water. The next day newspapers reported that his body was found in the waters of the bay near Bay 17th Street. While some initial reports claimed death by suicide, the family firmly believed it was an accident and police found no evidence of foul play.

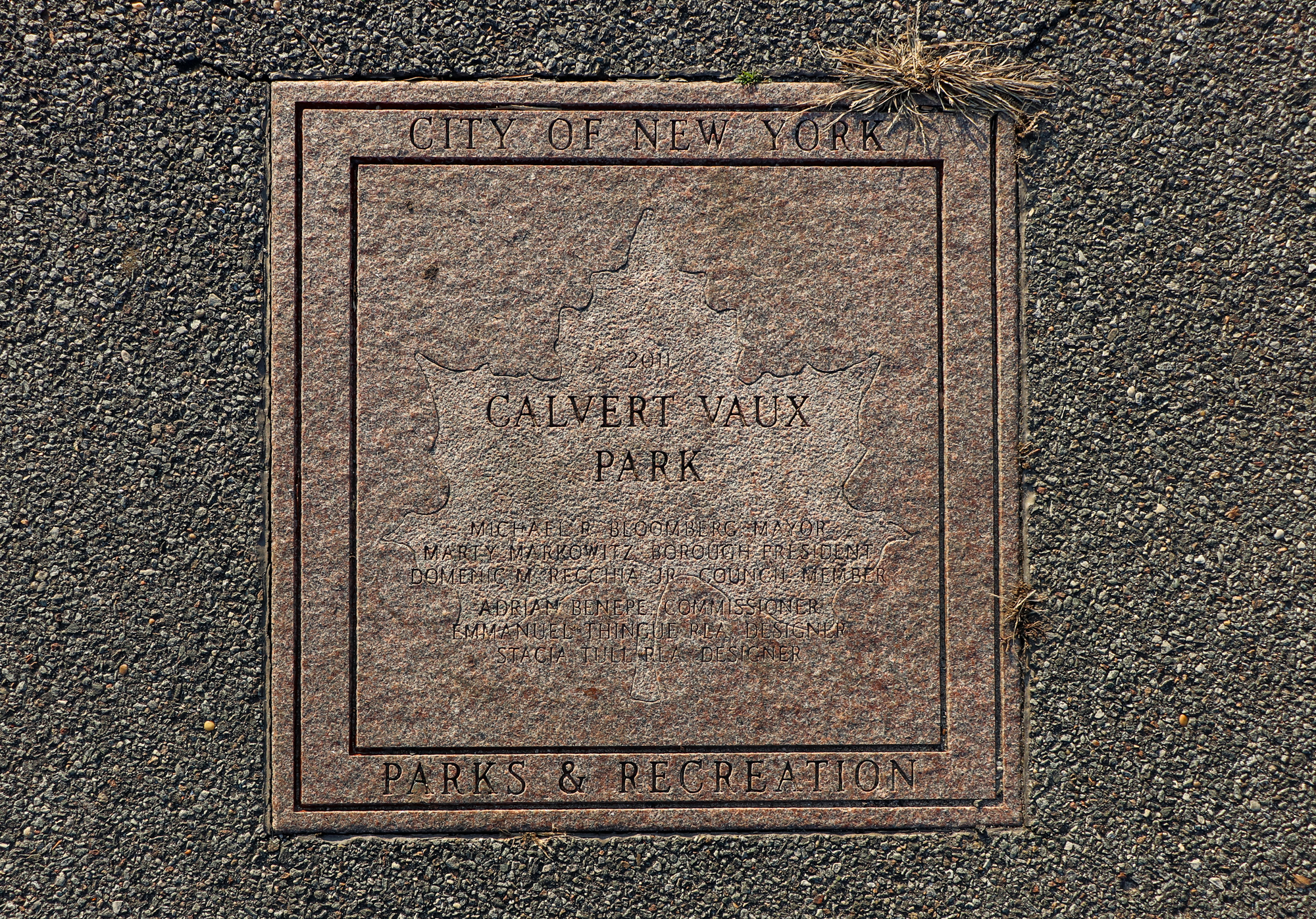

While the park, once known as the Dreier-Offerman Park, was dedicated to Vaux in 1998, the landscape and shoreline would have been vastly different during his time. Land for the park was accumulated by the city starting in 1933 with the acquisition of the property of the Dreier-Offerman Home for Unwed Mothers.

More land was acquired over the decades, including the purchase of more than 70 acres made possible through a 1960 New York State Bond Act. At the time, the New York World-Telegram and Sun reported that Park Commissioner Newbold Morris acknowledged that the parcel consisted “mainly of land underwater” and construction of park amenities would only be possible with infill. Some of that infill would eventually come from the construction of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.

It took decades for a fully planned park to become a reality. By the 1990s, while there were some ballfields and recreation areas, most of the land was undeveloped and with illegal dumping rampant, Parks Commissioner Henry Stern told the New York Times in 1997 that “it’s been an open dump.”

The park was named in honor of Vaux in 1998 and today it’s a mix of busy athletic fields and slightly wild pathways. A bridge constructed circa 1940 provides access over the Belt Parkway.

A recent winter’s day provided a quiet ramble through a portion of the now 85-acre park. There are formal pathways around planters that are no doubt lush and blooming in the summer. More rugged pathways lead to the secluded shoreline and a chance to walk a sandy stretch with the rotting remains of boats and piers. Parks signage (currently covered in graffiti) highlights the creatures to be found, including horseshoe crabs, ribbed mussels, fiddler crabs and great egrets.

Related Stories

- Calvert Vaux, Architect

- Take a Seat on a Piece of Engineering History in Prospect Park

- Bridging Nature With New Technology: The Cleft Ridge Span of Prospect Park

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment