The Opulent Splendor of Downtown Brooklyn's Lost Fox Theatre

Downtown Brooklyn once had a theater district as vibrant as Manhattan’s, with almost as many venues, offering the gamut of entertainment from opera to Shakespeare, popular slapstick comedies to classic dramas, vaudeville to minstrel shows.

The Fox Theatre in 1970. Photo by Jack E. Boucher for the Historic American Building Survey via the Library of Congress

Editor’s note: This story is an update of one that ran in 2011. Read the original here.

Downtown Brooklyn once had a theater district as vibrant as Manhattan’s, with almost as many venues, offering the gamut of entertainment from opera to Shakespeare, popular slapstick comedies to classic dramas, vaudeville to minstrel shows.

In the early to mid-1800s, most of these theaters were gathered around the area where Cadman Plaza is today, as well as on Fulton Street, near Gage and Tollner.

By the end of the century and into the 20th, the theater district had moved closer to Flatbush Avenue, and was centered still on Fulton Street, as well as Flatbush, Nevins and Fleet Street.

All of these locations had stories to tell, but today’s tale is about the largest and grandest of Brooklyn’s four great movie palaces. Brooklyn had the RKO Albee Theatre, the Brooklyn Paramount, the Loew’s Metropolitan and — the largest and most opulent — the Fox Theatre.

The Fox Theatre’s address was 20 Flatbush Avenue, at the intersection of Nevins, Flatbush and Livingston streets. The cornerstone was laid in September of 1927, and the Fox opened with much fanfare in August of 1928.

The large building was designed by C. Howard Crane, a Detroit-based architect who specialized in theaters and movie houses. In the course of his career, he designed over 250 theaters, including more than 50 in the Detroit area alone.

He was the designer of several of the Fox company’s other theaters, including the 5,174-seat Fox Theatre in Detroit, followed by the slightly smaller 4,500-seat Fox Theatre in St. Louis. The Brooklyn Fox was the smallest of the three, with a mere 4,305 seats.

The Fox chain was the brainchild of movie mogul William Fox. He was an immigrant success story worthy of his own motion picture. He was born Vilmos Fried in 1879 or 1880 to German-Jewish parents living in Hungary, and he came to this country with his parents as a 9-month-old baby.

The family name was Anglicized to Fox, due to his mother’s maiden name Fuchs. He grew up dirt poor on the Lower East Side, managing to reach adulthood without ever learning how to read and going to work from the age of eight.

A childhood accident robbed him of the use of one of his arms, but neither illiteracy nor handicap would deter Fox from success.

In 1900, when he was 20 years old, he started his own textile company, which he sold four years later to finance the purchase of his first nickelodeon. In 1914, he began the Fox Film Corporation.

Fox Films was more about distribution than movie making, and Fox was more interested in movie theaters than heading a studio.

In 1925, William Fox began his ambitious plan to build enormous and ornate movie palaces — the largest movie houses ever. That year, he also bought the rights to a new integrated sound-on-film system invented by three Germans and one American, Theodore Case.

He renamed the system Fox Movie-tone, and it was one of the earliest film soundtrack systems in the industry. His Movietone Newsreels, with the news of the day, would be a theater staple until 1963.

By 1928, he had five enormous theaters, all called Fox, in San Francisco, Atlanta and, as mentioned, Detroit, St. Louis and Brooklyn.

Brooklyn was also home to a smaller 2,000-seat theater called the Savoy, on Bedford Avenue near Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights. Until the downtown Fox was built, it was the largest Fox theater in Brooklyn.

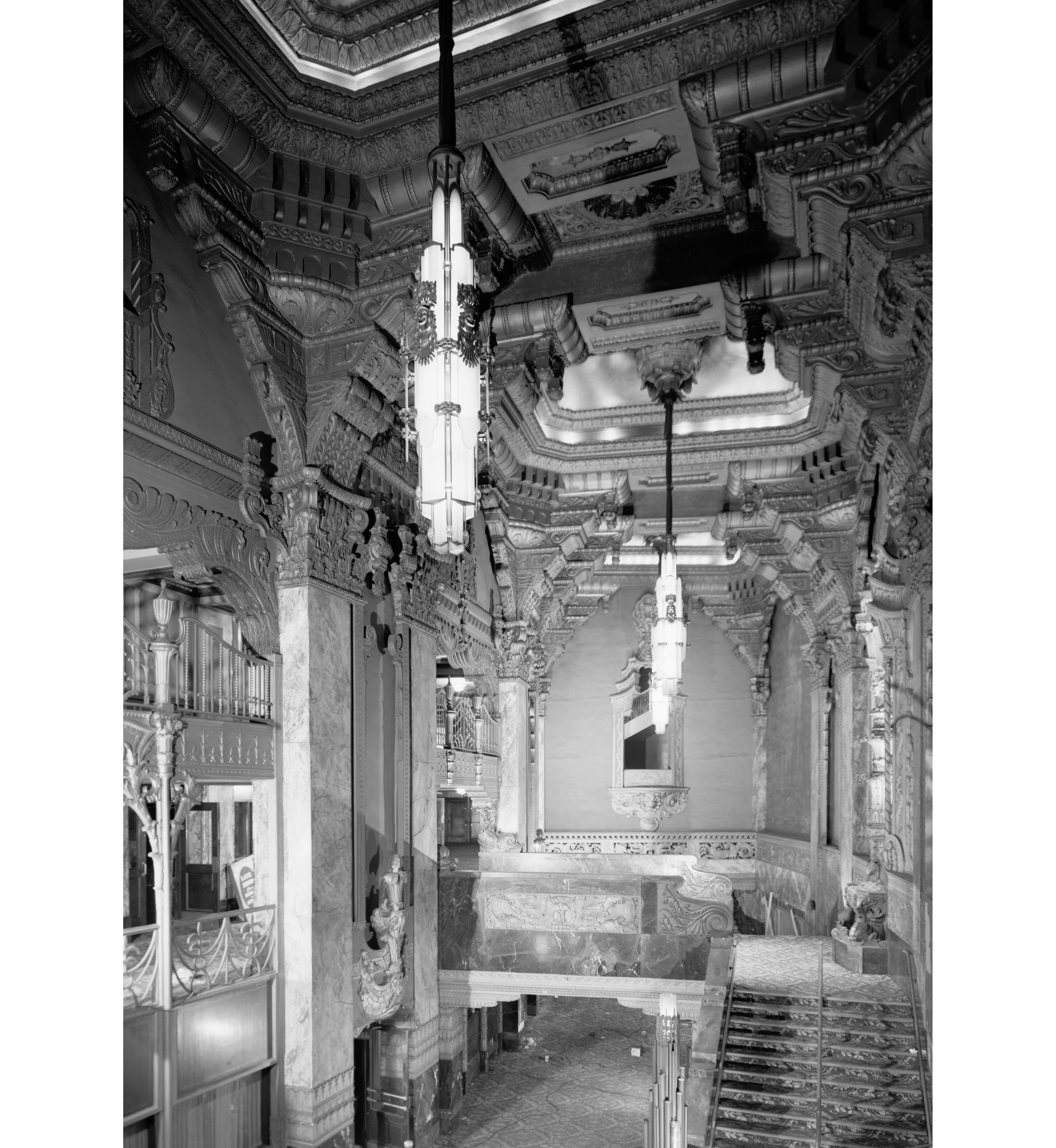

And what a theater it was. From the outside, the Brooklyn Fox looked like an office building with a marquee. There were offices inside, as well as retail stores on the ground floor. But the inside of the theater was a different story.

The style could only be called over-the-top eclectic. It was Baroque on steroids, combining elements of India and the East Indies with Baroque and Art Deco.

Every surface of the theater was decorated, gilded, draped, carved, painted, polished or plastered. The grand lobby rose four stories high, with a massive staircase leading to the levels of the theater.

The opulent restrooms lay downstairs, and passageways and smaller stairs brought patrons to the various parts of the theater. There were no elevators for the theatergoers.

The proscenium opening was 50 feet wide and 35 feet high, with the lip of the stage cantilevering over the orchestra pit. The height of the auditorium from the orchestra floor to the ceiling was 96 feet.

The seats rose at a steep angle on the balconies and above. The horrible acoustics in most of the mezzanine was little deterrent to those who wanted to be there to just take in the experience.

This was not just a movie palace; it was a real theater, with ample room backstage to swing in and build sets, single and multiple dressing rooms, rehearsal, chorus, and orchestra rooms below stage level and, upstairs, a music library and rehearsal rooms on the eighth floor and a costume-making shop on the ninth.

The theater also boasted one of the five Fox Specials Wurlitzer organs — this one with four keyboards and 37 ranks of pipes.

Aside from the usual organ effects, this instrument had special stops with snare drum, bass drum, Chinese gong, castanets, tambourine and other musical effects, as well as a junk board with the sounds of surf, auto horns, birds, horse hoofs, and boat and locomotive whistles.

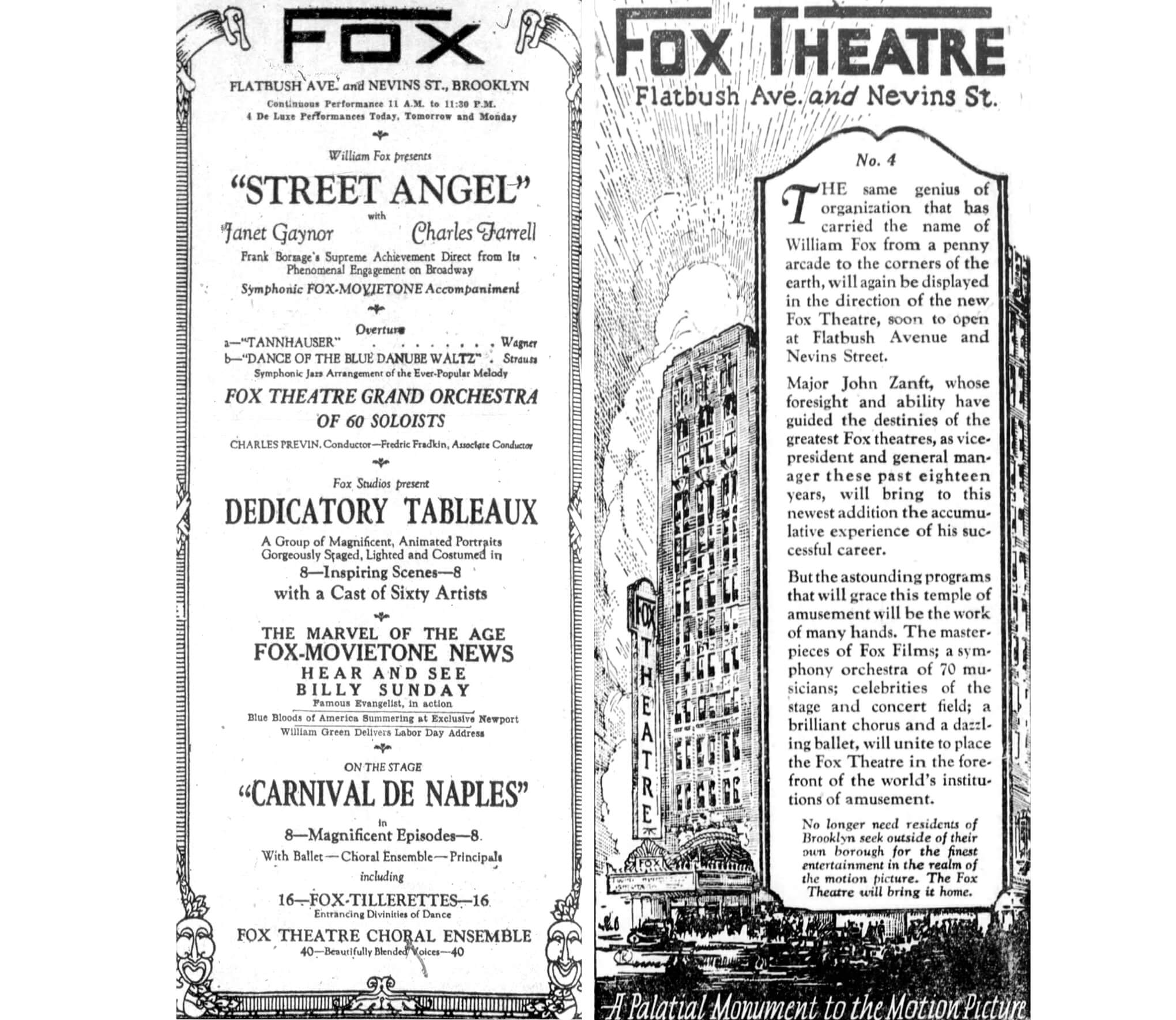

Opening night of the Fox in 1928 was a splendid affair, attended by Mr. Fox as well as Brooklyn dignitaries, special guests and a lot of other people.

They were treated to Charles Previn leading the 70-piece Fox Theatre Grand Orchestra in Wagner’s Tannhauser Overture and a jazz arrangement of the Blue Danube Waltz.

This was followed by Fox Movietone News clips, and a short film showing playwright George Bernard Shaw mimicking Benito Mussolini.

That was followed by a stage show of dancing and choral works with a Neapolitan theme, followed by the running of the feature film Street Angel, set in Naples and starring Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell.

This grand opening heralded several years of stage and screen shows for the Fox, as the corporation went on to reach 800 theaters, with the company valued at $200 million by 1929.

The Fox Metropolitan Theatre Corporation, which controlled all New York City theaters, had a total seating capacity of 140,000 people.

In July of 1929, William Fox was in a near-fatal car crash that put him in the hospital for three months. Unfortunately, that was only his first crash of 1929.

By 1933, Fox Film Corp. was in receivership. By 1936, William Fox declared bankruptcy.

The Great Depression, as well as Fox’s own overreaching, came simultaneously and came down hard.

On November 4, 1930, the crowds were so great in front of the Fox Theatre that the police were called to keep people from crushing in the first floor shop windows. But behind the scenes, things were not going well.

The Friday before the 1929 crash, he had realized $20 million from sales of assets. The following Tuesday, that sale was worth only $6 million, and continued to drop.

His stock went from $119.00 to $1.00 a share. In 1932, one of his creditors filed suit, claiming default by Fox on a $13 million bond issue.

He demanded the appointment of an equity receiver for Fox Metropolitan Playhouses Inc., which owned all of the New York Fox theaters. In February of 1933, the Brooklyn Fox closed. Its employees were given two weeks’ notice, and the public was told the purpose of the closure was to expand the stage.

A few weeks later, the theater reopened, but it was soon to be under new management.

Theaters may have been William Fox’s love, but he was still a movie mogul, and Fox Pictures was one of the industry’s top producers and studios. Back in 1927, Fox had bought the Loew family holdings of rival studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer upon the death of studio head, Marcus Loew, intending to merge Fox Pictures with MGM.

This infuriated MGM studio heads Louis Meyer and Irving Thalberg, as they were not shareholders, and Fox would have become their boss. Meyer used his legal connections to have Fox accused of antitrust violations, income tax evasion and even trying to loot his company.

The triple whammy of Fox’s automobile accident, his losses because of the stock market crash, and the resulting bankruptcy, killed the deal, and the merger did not take place.

The legal wrangling cost him control of Fox Pictures. He had already lost control of the theaters. However, in a move of incredible stupidity, Fox tried to bribe the judge in his bankruptcy hearing and committed perjury.

He was indicted, pled guilty, and served six months of a one-year jail sentence. When he got out, in 1936, William Fox was done, no longer in the film business. The studio had been transferred to a new president, Stanley Kent.

In 1935 Kent merged Fox Pictures with a new company called Twentieth Century Pictures. The combined firm, 20th Century Fox, under Darryl Zanuck would become a legendary film studio in the Golden Age of motion pictures. William Fox died in 1952. Not one single Hollywood producer came to his funeral.

Back in New York, in 1933, the Loew-Warner Corporation attempted to buy the Fox Metropolitan Theater Corporation. They were outbid by another theater chain, Fabian Enterprises, and the Brooklyn Fox Theater, along with the other New York City theaters, now belonged to Fabian.

They didn’t change anything, and moviegoers continued to patronize the venue. The Depression ended the big stage extravaganzas, but the movie-going public stayed loyal to the theater for at least another 20 years.

In 1934, William Fox’s old office suite became headquarters for radio station WBNY, which gave them access to activities on the Fox stage. They broadcast radio amateur-hour contests for talented kids, until running afoul of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, which resulted in fines and a one-day closure.

In March of 1945, the theater stopped having amateur night as a drive against bobby-sox juvenile delinquency in movie theaters, according to news reports at the time.

The invention of television took the motion picture world by storm, creating competition that exists to this day, but the Fox Theatre took it in stride by broadcasting the first closed-circuit telecast shown in theaters: a prize fight from Chicago, brought to New York via coaxial cable through an arrangement with RCA and NBC.

They would broadcast other sporting events, including the 1949 World Series and college football games.

Other important broadcasts included addresses from presidents Truman and Eisenhower and the December 11, 1952 broadcast of Bizet’s Carmen, starring Brooklyn natives Richard Tucker and Robert Merrill.

A riot almost occurred during the Sonny Liston-Floyd Patterson fight in 1962, when the screen went dark right before the knockout, and more than 4,000 fans had to be promised refunds for the $7.50 tickets, for a fight that lasted only two minutes and six seconds.

In 1955, the Fox was home to a series of live rock-n-roll stage shows, a tradition that continued until 1966. Disc jockey Alan Freed hosted the first of the concerts in the 1950s, and he was followed by radio dj Murray Kaufman.

Murray the K, as he was known, featured popular acts of the 1960s. He was famous for integrating his shows well before that was matter of course, bringing black, white and Latino artists under the same roof.

He usually produced four shows a year, each featuring a multitude of acts. One marquee from the early ’60s featured Little Stevie Wonder, the Drifters, the Shirelles, Ben E. King, Gene Pitney and the Miracles.

As popular as the Murray the K shows were, they were not enough to keep an enormous theater like the Fox afloat. By 1966, the knockout punch of flight to the suburbs, urban blight and television had brought down the cinema house.

Attendance at the 4,300-seat theater was down to 100 people. On February 6, 1966, the Fox ceased to be a movie theater, and its 70 staffers were laid off.

For the next two years the huge theater hung in limbo, unsuccessfully opening as an opera company for a few months — and there were a few more rock concerts. A Humphrey for President rally took place here, and then the doors closed forever.

The marquee read “Temporarily closed, for rent.” In 1971, the magnificent Wurlitzer organ was removed (it ended up in a private home in Washington State) and the building was torn down.

Officially, none of its architectural features were salvaged — not the lights, the decorative railings, fixtures, movie seats, or anything else. Period photographs show the bulldozers just ripping through the building.

Today, the site is home to a Con Edison office building, a bland structure that would be at home in any suburban office complex.

William Fox’s monument to the glory of the movies, the extravaganza of a full-blown stage experience, and his own massive ego, is remembered only by Brooklynites of a certain age, and seen only in a few black-and-white photographs that can’t entirely show the magnificence that was the Brooklyn Fox Theatre.

[Photos taken by Jack E. Boucher in 1970 for the Historic American Building Survey via Library of Congress unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- The Glamorous, Magical Fantasy World of Loew’s Pitkin Avenue Theater

- The Court Theater of Carroll Gardens: From Showing Films to Repairing Cars

- The Glorious Rebirth of Brooklyn’s Wondrous Kings Theatre

Sign up for amNY’s COVID-19 newsletter to stay up to date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment