Walkabout: The Arbuckle Coffee Company's Sugar and Coffee War, Part 3

Read Parts One and Two of the Brooklyn coffee history series. John and Charles Arbuckle came to Brooklyn from Pittsburgh and built the largest coffee company in the United States. By the early years of the 20th century, their operation in Dumbo received, stored, roasted and packaged more coffee than any other company in America….

Read Parts One and Two of the Brooklyn coffee history series.

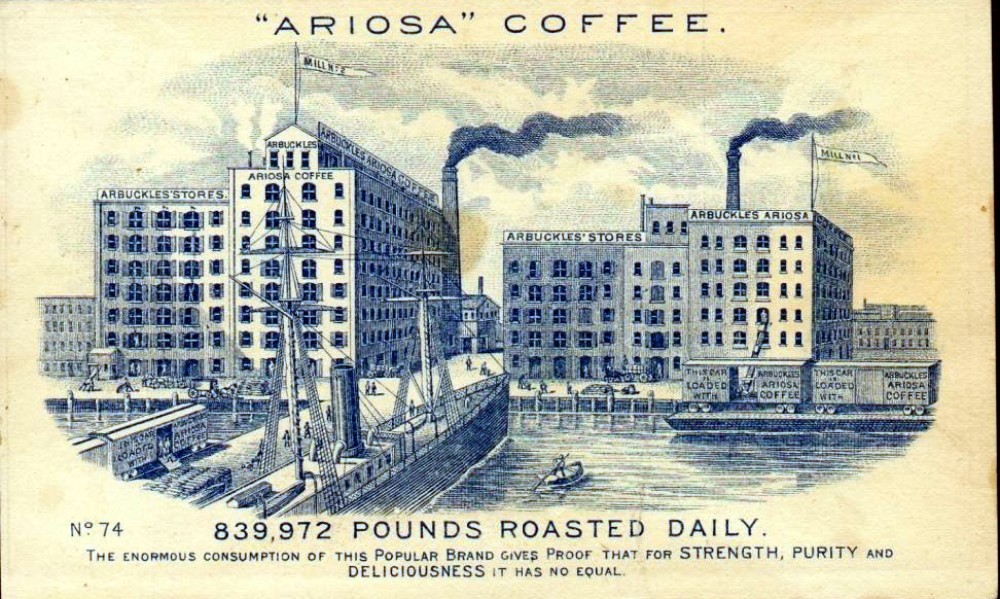

John and Charles Arbuckle came to Brooklyn from Pittsburgh and built the largest coffee company in the United States. By the early years of the 20th century, their operation in Dumbo received, stored, roasted and packaged more coffee than any other company in America.

Their signature brand, Ariosa, was packaged in small, one-pound, branded packages of freshly ground coffee. It was sold everywhere in the country.

Ariosa was nicknamed the “cowboy’s coffee,” as it was the brand of choice for cowhands on the range. The iconic cowboy campfires with the coffeepot on the fire, later copied into movie and television legend? They were drinking Arbuckle Ariosa.

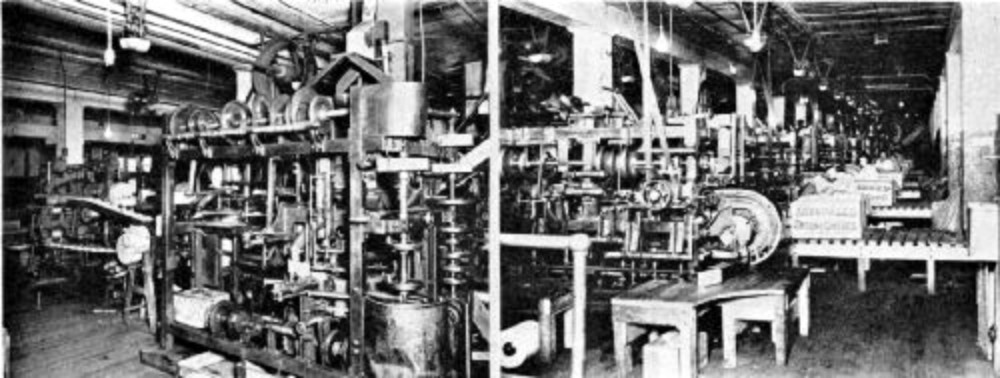

Arbuckle’s success lay in the roasting process. John Arbuckle invented most of the company’s innovative methods and machines, then wisely patented them, further adding to the company’s revenues.

His first invention was a process using eggs and sugar in a glaze that coated the raw beans, sealing in the flavor. His patented roasting machines took care of the rest.

Photo via All About Coffee by William Ukers

The Sugar and Coffee War

Elder brother Charles Arbuckle died in 1891, and John brought his nephew, William Arbuckle Jamison, on as a partner, as well as two trusted employees.

The company was still growing and needed more and more sugar for its refining process. Arbuckle had been buying sugar right down the road, from Williamsburg’s enormous Havemeyer Sugar Company, which processed Domino sugar.

Because the companies were so close, barges or ships could simply make a short run around the harbor to deliver the products.

Arbuckle tried to cut a deal with Havemeyer, given the vast quantities they used, but Henry O. Havemeyer wasn’t having it because he felt threatened by Arbuckle’s domination of the industry.

The Arbuckles were smart. Not only did they import more coffee from South America than anyone else, but they also owned the ships that carried the coffee.

Arbuckle warehouses along Brooklyn waterfront. Photo via All About Coffee by William Ukers

They owned the warehouses and factories, and even built a railroad track through Dumbo to facilitate shipping materials and product.

Arbuckle owned the patents for coffee roasting, as well as for the machines that roasted it. When another inventor patented a machine advancing the coffee business, Arbuckle either purchased the patent or went into a partnership with its owner.

Arbuckle was also a master of advertising and packaging and his brand was everywhere. Every package of Ariosa came with redeemable coupons and had a stick of peppermint inside to sweeten the deal.

Although there were other successful coffee manufacturers in New York and elsewhere, Arbuckle was a force to be reckoned with — the King of Coffee.

Havemeyer was the King of Sugar, but since he refused to cut a deal, John Arbuckle in 1896 announced that he was going to open his own sugar refinery.

The refinery was built in 1897 on the corner of Jay and John streets. It could produce 3,000 barrels of sugar per day, much of which would be packaged in retail-sized two-pound paper bags.

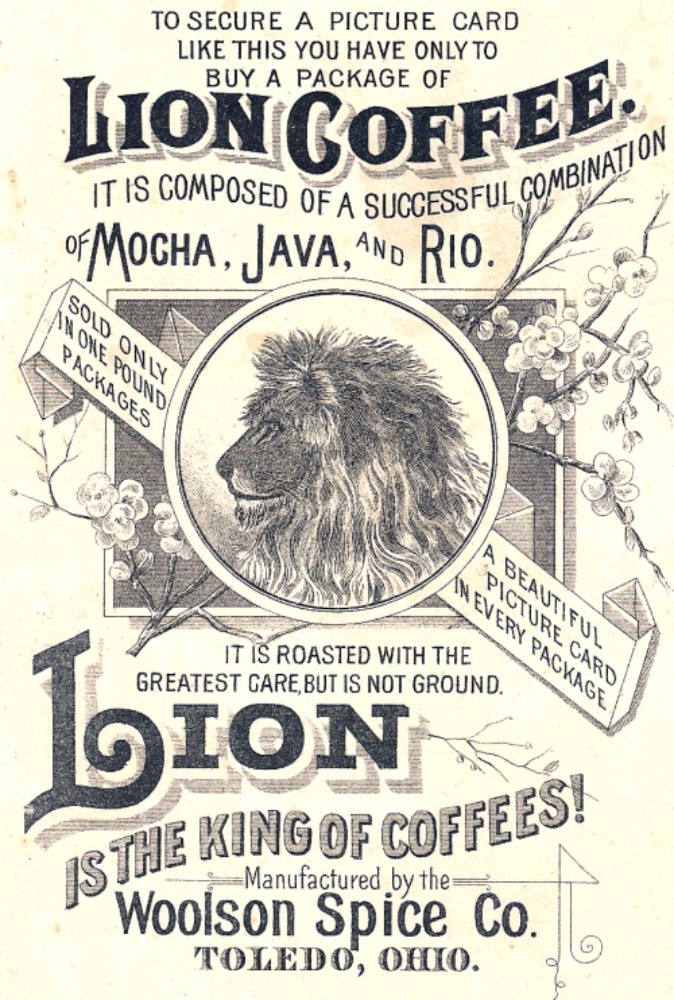

Havemeyer retaliated by buying the Woolson Spice Company of Toledo, Ohio, a major coffee-roasting business. Their main product was a coffee marketed nationally under the Lion brand.

This was the beginning of the Sugar and Coffee War.

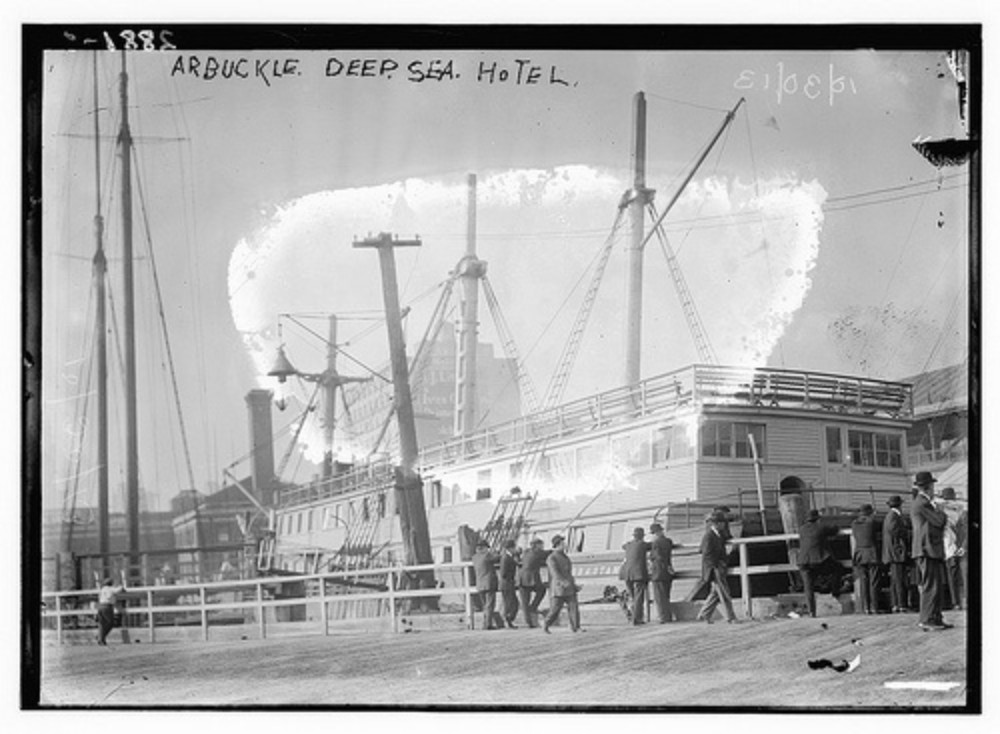

Photo via Authentic Boats

The “war” lasted several years. Arbuckle had the industrial facilities to refine his sugar and a sales organization already in place to market it. His refinery upped its production to 5,000 barrels a day.

Henry Havemeyer put himself on the board of Woolson, and poured an unheard-of amount of money into advertising to push Lion coffee into the marketplace, touting its superiority over Ariosa.

The battles went to the courts as well, with the lawyers on both sides getting rich. Both sides spent astronomical amounts of money — an estimated $25 million, all told. The war between the two companies was so fierce and pervasive that the price of both coffee and sugar was depressed for much of the battle. Everyone in both industries suffered for it.

In the end, Havemeyer folded. They gave up the coffee business. Arbuckle continued to refine his sugar. His business grew, although there was some controversy regarding taxes and duties.

Sugar was the cause of this, with allegations that they were under-weighing the crude sugar as it came into port, and were not paying their share of taxes and duties on it. Without accepting blame, Arbuckle paid the government close to $700,000 in back duties. Over at Havemeyer, similar allegations resulted in $2 million in back duties.

Photo from Library of Congress, via New York History Walks

John Arbuckle’s Philanthropy

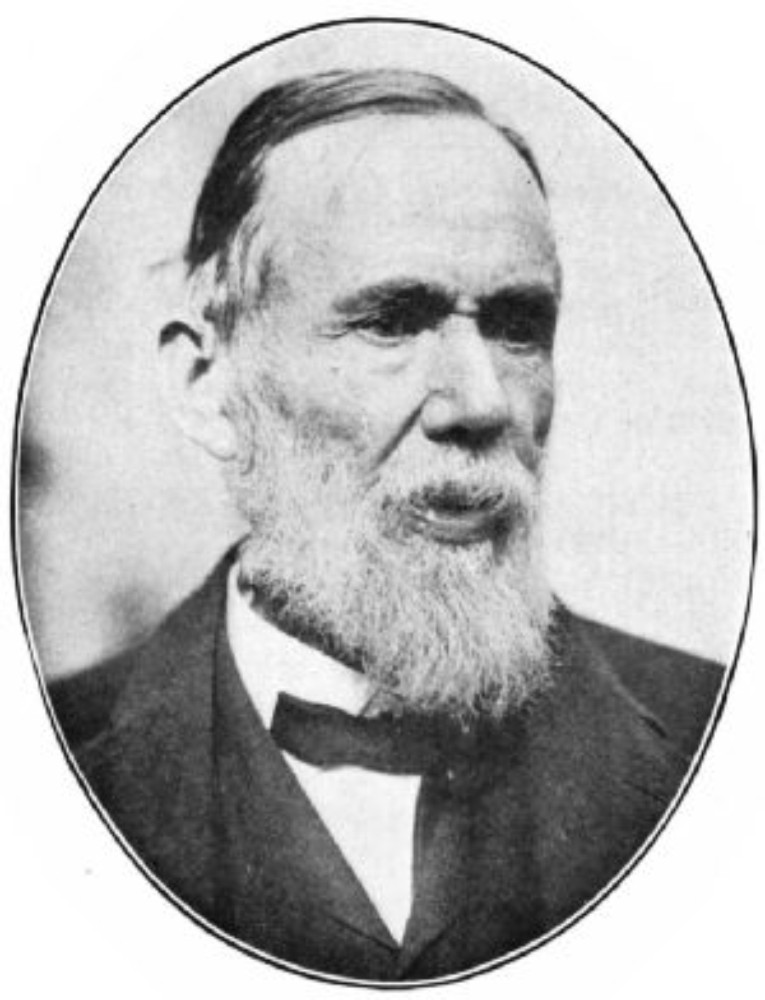

John Arbuckle was one of Brooklyn wealthiest men. He was also generous — he and his wife gave to many worthy causes and established a few of their own.

He took an old full-rigger ship in New York Harbor and turned it into a home for working men and women. He called it his Deep Sea Hotel. He also established a vacation home in New Paltz called the Mary and John Arbuckle Farm, where workers could take some time off.

He valued vacation and leisure time, something the average factory worker had very little of, and tried to give them at least some relief from the daily toil. He established boat trips for children, as well as vacation trips for his workers. He also established a periodical for children called Sunshine Magazine.

Early-20th-century John Arbuckle photo via All About Coffee by William Ukers

The Arbuckle Legacy

In late March of 1912, John Arbuckle didn’t feel well and took to his bed. Four days later, on March 27, he died at his home at 315 Clinton Avenue. He was 75. The Arbuckle Brothers plant and the Coffee and Sugar Exchange in Manhattan closed early the next day in tribute. His funeral was packed.

John Arbuckle made his fortune in Brooklyn, but is buried with the rest of his family in Allegheny, Pennsylvania. His beloved wife Mary had died in 1906. John Arbuckle left an estate of over $33 million. A bequest in his will established the Arbuckle Memorial at Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights, where he and his wife were members.

Arbuckle Brothers continued under the leadership of the nephew and his partners. The company’s growth continued. In 1913, they introduced a new coffee called the Yuletide Banquet.

Ad via All About Coffee by William Ukers

It was a premium coffee, a superior blend to their best-selling Ariosa and cost a bit more. It had been John Arbuckle’s personal blend, which he gave as a present during the Christmas holidays.

Yuletide Banquet was soon competing with Ariosa as the company’s signature blend. The name had been shortened to Yuban. Today, Yuban coffee is still on the market and still selling well.

At the company’s height, in the ‘teens, Arbuckle Brothers occupied a dozen city blocks along the waterfront in Dumbo. Their business was completely self-contained — they didn’t outsource anything.

Postcard via New York History Walks

The buildings in the complex stored the beans. They were sorted, glazed, and roasted in their plants. The coffee was ground, packaged and shipped there. The sugar refinery did the same with the sugar.

They had a stable full of horses and wagons for deliveries. That later changed to delivery trucks of all sizes. They even had a laundry that washed and dried the woven bags that the sugar and coffee arrived in, for re-use. Off-site, they established a barrel factory that made their own shipping barrels.

The factory had a hospital and a large, airy dining room for employees. The Arbuckles had a large print shop where they printed all of the labels and branded packaging and advertising. One of the company’s successful campaigns involved collecting value stamps that could be redeemed for goods.

Arbuckle coffee packaging machine. Photo via All About Coffee by William Ukers

The stamps were printed on the coffee labels and were collected in books. All kinds of merchandise, from handkerchiefs to dishes, jewelry and other items were obtained. The Arbuckles established a separate company to take care of the redemption, which grew to become a large enterprise in of itself.

From this, they established the Charles William Stores, a very successful mail-order business. It did not have the Arbuckle name attached to it. The business was located in Dumbo, as well, and took up several buildings in the Gair complex on Washington Street.

The Arbuckle Brothers Company stayed in the family for at least two more generations. But by the 1930s, no doubt feeling the pinch of the Depression, the family began selling off the company. The only brand they held onto was Yuban.

One by one, the Dumbo factories were closed and sold off. The sugar refinery operated until 1945, when it was sold as a whiskey warehouse. It later became a warehouse for Abraham & Straus. The other buildings in the complex had similar histories, and some were torn down. Today, most are residential or mixed use.

Today, Yuban Coffee is now a cheaper grade of supermarket coffee. A new Arbuckles Coffee — hand roasted in Arizona, 100 percent organically grown and fair trade — is now available. This new company has revived the Ariosa label and markets their coffee based on a combination of the Old West legend and the new artisanal coffee craze.

They even enclose a stick of peppermint in their packaging, just as John Arbuckle did. Then, as now, it sweetens the deal.

1914 ad via Attic Paper

[Top photo: All About Coffee by William Ukers]

Related Stories

Walkabout: The Arbuckle Coffee Company, Brooklyn’s Other Great Brew

Walkabout: King Coffee, the Magic Beans that Powered Brooklyn

Building of the Day: 315 Clinton Avenue

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment