How the Railroad Brought Meatpacking to Fort Greene

Nothing remains of the once-thriving industry that was fueled by Long Island’s demand for fresh meat, the railroad, and the labor of hundreds of people.

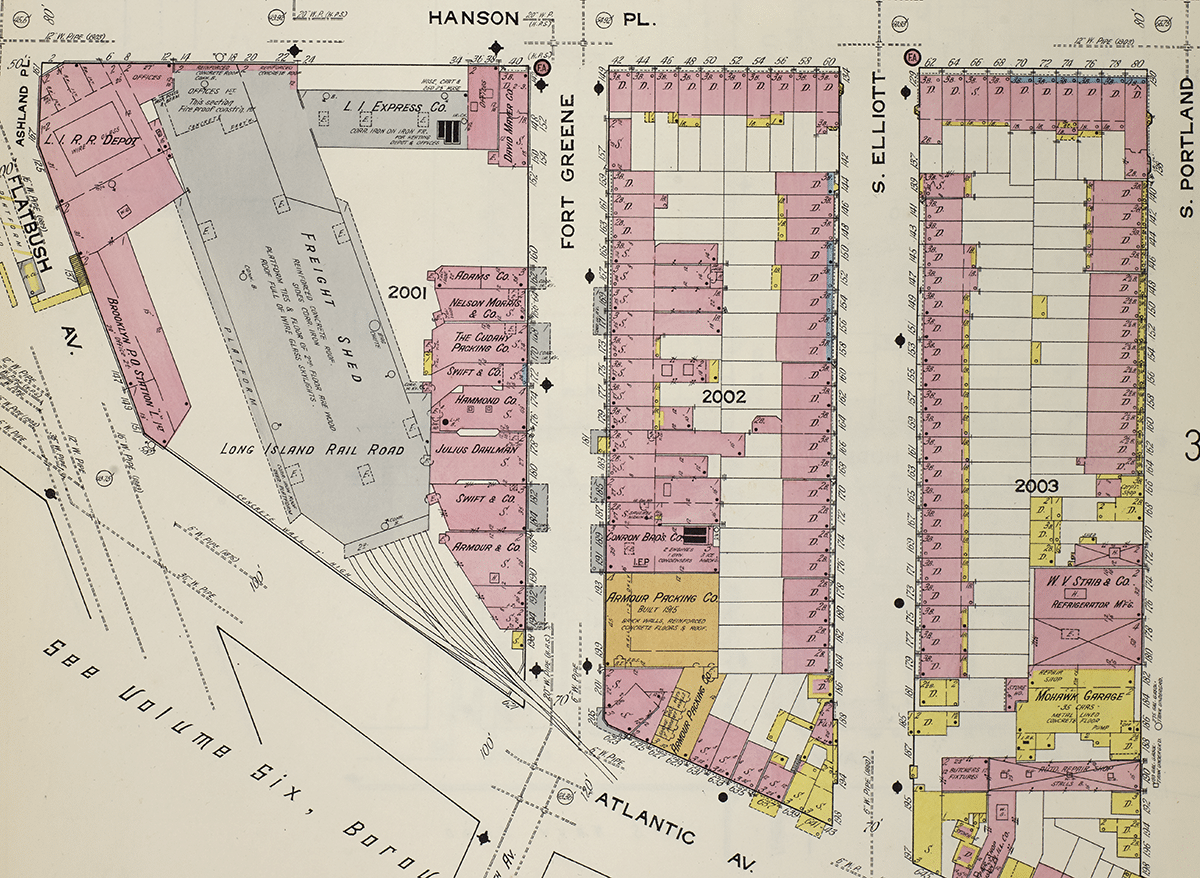

A 1926 aerial view of South Elliott Place between Hanson Place and Atlantic Avenue. Photo by the Brown Brothers via New York Public Library

Before 1898, Brooklyn was a wealthy, independent city with its own government, police and fire departments, school system, and more. Throughout the 19th century as the city grew, commercial and cultural districts flourished. Brooklyn had its own theater district, government center, shopping quarter, and several industrial and manufacturing sections, to name a few. One of those busy industrial areas was Wallabout, along the East River in what is now Fort Greene and Clinton Hill.

After the Civil War, businesses related to the grocery and food industry, such as bakeries, candy manufacturers, wholesale grocery warehouses, cold storage facilities, packaging factories and other food related businesses congregated heavily in Wallabout. It didn’t hurt that the sugar refineries of Williamsburg were right next door either. The tantalizing smells of candy, sweets, and baked goods wafted through the air, along with the less pleasant smells of the area.

The sugar refineries were not the only reason for this location to flourish for the food industries. It was very convenient for transportation. The streets were wide here. Ferries could transport goods across the East River to Manhattan, and after 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge made surface transport easier as well.

It makes sense that a wholesale and retail food market would be established here. In 1884, what started out as a group of random buildings clustered near the Brooklyn Navy Yard became a vital part of Brooklyn’s economic development. So much so that the city decided to build a permanent market in 1894. The new Wallabout Market, designed in a Dutch and Flemish inspired style by William Tubby, was a beautiful market, soon filled with all kinds of merchants and thousands of customers. Produce, dairy, meat and fish, as well as packaged foodstuffs were all sold in this successful venue.

Another meat market was established not all that far away, and around the same time. This one was primarily for meatpacking businesses. This market didn’t have a river behind it, but it had something equally important: the Long Island Railroad. The freight lines were able to deliver and ship meat right to the butchers’ doors. From 1892 to the 1970s, the Fort Greene Meatpacking District was a busy place, employing hundreds and supplying fresh cuts of meat across Brooklyn and Long Island. The railroad made it all possible.

The Long Island Railroad was established in 1835, running passenger trains down the middle of Atlantic Avenue from downtown Brooklyn to Jamaica, Queens. The railroad grew over the course of the century, adding more stations and lines in Queens and Long Island. After 1851, the terminus of the LIRR was at the junction of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues. A passenger terminal was built there, heralding the beginning of the area’s importance as a major public transportation hub.

The LIRR tracks were also an opportunity to develop a separate freight line. The Long Island Express Company was established in 1882, running freight trains from Long Island to the Atlantic Terminal and back. The Fort Greene Meatpacking District was established there because of those freight lines. Starting in 1892, meatpacking companies began building their wholesale and retail businesses on Fort Greene Place between Atlantic Avenue and Hanson Place. Some businesses also spilled over on Atlantic Avenue.

The meatpacking companies built solid masonry buildings catering to the needs of their industry. Some of them were quite beautiful, but all had expansive street-front loading docks where meat was received and shipped out. Manhattan’s Gansevoort Meat Market has many of the same kind of buildings still standing, all of which are now restaurants, galleries, and shops.

In 1903, the railroad underwent a major upgrade and renovation. A new passenger terminal was built on the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush, a large classically inspired train station worthy of the location’s importance. The Times Plaza Post Office was attached to the terminal along Atlantic Avenue until 1925. The freight component of the area was massively upgraded as well. The freight tracks veered off between Fort Greene Place and the station, terminating in a large train yard in the center of the block. One track led to a turntable, which could turn the engine back towards the exit. The tracks there ended in the backyards of the row houses on Hanson Place, a Sanborn map of 1904 shows.

As the meatpacking area grew, a covered freight terminal building was constructed to cover the tracks in 1905. It belonged to the Long Island Express Company which had a substantial office building on Hanson Place. The terminal building had brick walls and a metal roof supported by trusses, with a third of the roof glassed in the center. It was further lit by hundreds of hanging metal work lights. Businesses along the terminal could access the tracks underground through freight elevators. The tracks had overhead conveyor systems where sides of beef and pork could be loaded on hooks and sent on their way to the meatpackers.

LIRR historian and expert Arthur John Huneke has a great section on his railroad blog on Brooklyn’s terminal and meat market, with wonderful photos of the freight terminal and the meat houses’ elevators to the railway.

Beef, pork, poultry, and other slaughterhouse products were brought in by train, by wagons and, later, by trucks. They could drive into the terminal and load up along the platforms. Seventy-five percent of Brooklyn’s beef was processed along Fort Greene Place. Most of the businesses were relatively small and specialized, but two large meatpacking giants, the Swift Company and the Chicago-based Armour Company, had large operations here.

Armour was the largest, and occupied several buildings on Fort Greene Place, one of which spread around the corner on Atlantic. Armour had their own train track, which rose from the Vanderbilt train yard past street level and crossed Atlantic Avenue via a covered bridge to Armour’s facilities. According to expert Huneke, at least part of the bridge dates back to 1899, showing that the meat market was up and running even before the rail yards were updated.

While the businesses here were primarily wholesale, some local butchers were also here. The Fort Greene Retail Meat Market at 174 Fort Greene Place was a popular local butcher featured often in the Brooklyn Eagle, especially during a beef shortage in the World War II years. The market also had kosher butchers, provisions merchants (cold cuts and sausages), and poultry vendors.

Other related businesses were also located in the immediate area: wholesale food merchants, packaging companies, and more. The Ward Bakery was only a couple of blocks away on the other side of the tracks on Pacific Street. They were one of the largest commercial baking companies in the city. The neighborhood was a busy one, with trucks crowding the streets and trains leaving hourly delivering fresh meat and bread to stores, restaurants, and other customers from Brooklyn to Montauk.

The Merchandise Freight Terminal was not successful, however, and by 1937, the shed was decommissioned. The section closest to Atlantic Avenue was sold to J. Rabinowitz & Sons, purveyors of glass containers and the owner of Rabinowitz’s Paramount Poultry at street level. But the market continued to be strong through the World War II years on into the 1950s. But dramatic changes were coming.

By the mid-1960s, both the city and federal authorities decided that the meatpacking district was no longer up to federal health standards and plans were made to move the market and the industry somewhere else in Brooklyn. Seeing the handwriting on the wall, many companies began closing in anticipation of a move. The market was in decline anyway, as demand for meat fell after the boom war years, and as large suburban supermarkets began sourcing their meat elsewhere.

The butchers and other packers began relocating their businesses to the new market at the Brooklyn Marine Terminal in Sunset Park. Photographs of Fort Greene from 1978 show parts of the market still standing. The elevated track and bridge had been torn down. Buildings were deteriorating and many were now empty and unrentable. Fort Greene Place was starting to look post apocalyptic. The market also had taken a toll on the surrounding residential neighborhood.

Meatpacking, sausage making, and live poultry sales are not for the faint hearted. Putting it plainly, the entire area was filled with the constant stink of blood, rotting meat, and more. The row houses and tenements in the surrounding neighborhood were subject to the miasma of the abattoir in their backyards. Consequently, the buildings became home to poor people who couldn’t afford to go elsewhere. Their living conditions were abominable.

Way back in 1962, the New York City Planning Commission recommended a large-scale rehabilitation of the entire area, along with a new LIRR terminal. The project was called ATURA, for the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area. The master plan was to tear down the terminal, the meatpacking district, and the surrounding housing and rebuild the entire area with low- and middle-income housing.

But after this grand plan was announced and lauded, nothing happened. Over 10 years later, as conditions continued to deteriorate, other plans were floated in the 1970s. One plan included a new campus for Baruch College, along with housing, but that one died as the city was experiencing the worst financial crisis in its history, leading to the famous New York Daily News headline in 1975, “Ford to City: Drop Dead.” There would be no large urban renewal projects that decade.

In 1988, the now-abandoned meat market was the poster child for a failing urban center. Commuters taking the LIRR rarely set foot in the terminal anymore: It was filthy, all the shops and newsstands once inside were gone, drug dealing was rampant, and the place was scary. People would rather wait on the street, no matter what the weather was like.

The meat market was gone, leaving only abandoned and crumbling buildings, and the substandard housing wasn’t getting any better on its own. The city decided not to rehab the station, but raze the entire area, thereby creating a massive series of fenced-in empty blocks at the edge of downtown Brooklyn.

The LIRR was only accessible from a stairway in the Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower and a street shed in front of the empty lots. It would remain that way for another 30 years.

The first improvements came with new housing and the creation of the Village at Atlantic Center, a complex of three-family brick row houses that replaced the blocks of housing on the site. The first group of middle-income owners moved into the new homes in 1994. Then Forest City Ratner, the co-sponsor of the housing along with the New York Housing Partnership, developed the Atlantic Center shopping center, which opened in 1996.

It was one of the first urban shopping centers featuring national retail chains. The success of that project led Forest City Ratner to build a companion shopping center called the Atlantic Terminal, which opened in 2004 with Brooklyn’s first Target store. The MTA then approved a new LIRR terminal entrance, which opened in 2010.

The two shopping centers are located on the site of the Fort Greene Meatpacking District. Nothing remains of that once thriving industry that was fueled by Long Island’s demand for fresh meat, the industrial and rail technology that made it all work, and the labor of hundreds of people. The meatpacking district didn’t only employ butchers, but kept hundreds of laborers, bookkeepers, office workers, packers, and producers at work, especially during the lean years of the Great Depression and in World War II.

By the 1980s, interest in Fort Greene’s gracious row house architecture and the convenience of city living were beginning to draw people back to the city. The creation of two historic districts surrounding the area and protection of buildings such as the Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower and BAM helped bring new investment to the Times Plaza area, leading to the creation of a new performing arts district and tall apartment towers. Change is inevitable in any city, but it’s good to know what came before and why it was important. The Fort Greene Meatpacking District was one of the successful economic engines of its day.

Related Stories

- Food for Brooklyn: The Story of the Great Wallabout Market

- Our Beautiful Brooklyn Blocks

- Let’s Hear It for the Taxpayers

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment