Found: A Park Slope "Hot Sheet" Hotel as It Never Was?

Brownstoner readers may recall the seminal 1969 New York Magazine article “The Consequences of Brownstone Fever.” The author, Peter Hellman, recently got in touch about a curious Brooklyn-related find. He writes: It was just after midnight and I was heading home from a too-late dinner when a street vendor’s painting caught my eye. It was a…

Brownstoner readers may recall the seminal 1969 New York Magazine article “The Consequences of Brownstone Fever.” The author, Peter Hellman, recently got in touch about a curious Brooklyn-related find. He writes:

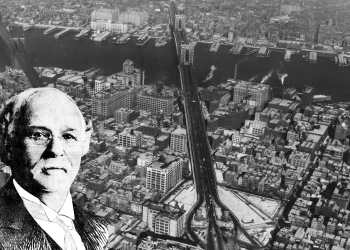

It was just after midnight and I was heading home from a too-late dinner when a street vendor’s painting caught my eye. It was a watercolor rendering of an ornate rock of an old building on whose entrance awning is written “153 Lincoln Plaza Hotel.” In a neat garden on the right side of the hotel, three guests sit reading. The cars at the curb are of 1970s vintage — one of two ways to give the painting an approximate time frame.

Curious about the building, I cut a deal with the vendor, a local street person in my Morningside Heights neighborhood. At home, a search of the AIA Guide to New York City showed that the building, located at 153 Lincoln Place, in Park Slope, had been built in Romanesque Revival style as the F.L. Babbott House in 1887. Its architect, Lamb & Rich, designed such landmarks as The Astral Apartments in Greenpoint, the Harlem Club (not far from where I live), and the main building of Pratt Institute. Then I clicked on a Brownstoner story which explained that 153 Lincoln Place was built for Frank Babbott, an industrialist whose wife, Lydia, was a daughter of oil magnate Charles Pratt. The story quotes from a Times Streetscapes column by Christopher Gray in which the prose verges on purple: “The craggy frieze of rock-faced blocks of brownstone above the first floor rolls and dives like a wind-tossed ocean. At the roofline, a delicate dormer struggles for place against the faceted turret, which in turn fights against the chimney on the side elevation, as well as a pair of flat arched windows, as taut as clock springs.”

But Gray’s flight of lyricism collides with the down and dirty conversion of the grand mansion into a “hot sheet” hotel sometime after the Second World War. In another Times story, this one by Wendell Jamieson, which appeared on April 18, 2004, a local resident named Pauline Muir told of her mother inquiring at the hotel about putting up a visiting aunt and uncle for one week. “$15 an hour,” she was quoted. Mrs. Muir tried again, explaining that this was an elderly couple. “$15 an hour,” she was told again. Though well known for its hourly trade, the hotel only once, so far as is known, experienced major crime. That was in 1999, when a woman was found strangled in one of its 26 tiny rooms.

About a decade ago, the building was bought for about $5.5 million by a local developer whose first thought was to turn it into an inn and restaurant. But it ended up instead as 10 condominium apartments. By the summer of 2010, they had sold out for prices ranging from $900,000 to $1,450,000 for a three-bedroom unit.

The building, once painted black, according to the Times, has been restored to its natural tones of pink, tan and red brick and stone. But in the painting I bought, the brickwork is painted a rich shade of blue, contrasting with tan bands of rusticated granite. The blue entrance canopy is capped by a red pyramid. In the lower right hand corner, the painting is signed “Henthorne,” a person who seems to have been trained in architectural draftsmanship. I made a few calls to Henthornes I found on Whitepages.com, but none knew anything about the painter. I had a little more luck estimating the vintage of the painting, thanks to the Bainbridge board on which the painting was executed. It’s branded “Charles T. Bainbridge’s Sons, Brooklyn, New York.” A Google entry notes that the company was founded in 1867 by a family living at 167 St. James Place. They had a summer home called Sunset Meadows in Cutchogue, on the North Fork. In 1984, the company was merged with the Nielson Company to become Bainbridge-Nielson, based in New Jersey. My painting, or at least its Bainbridge board, would seem to predate that merger.

I suppose I’ll never find out who the painter was or why he chose this subject, or how the painting ended up in the hands of a street vendor in Morningside Heights. I don’t know if the building was ever really painted blue or if that was an invention of the painter, but it makes an arresting sight with the matching car out front.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment