A Winter Wonderland: Ice Skating and Frosty Frolics in 19th Century Brooklyn

Organized skating began during the Civil War years, and Brooklyn’s earliest baseball fields were its first public skating ponds.

‘Skating Carnival in Brooklyn, February 10, 1862.’ Illustration from Harper’s Weekly via Library of Congress

The post-Civil War years were a period of great change in American society. For the first time, an ever-growing middle class emerged, one that had more leisure time than ever before and money to spend. Brooklyn was a manufacturing city back then. Its industrial hubs along the East River and further inland were supported by factories churning out all kinds of goods like furniture, glass, and porcelain, as well as foodstuffs, linens and lace, timepieces, and home furnishings. While many jobs were low-paying factory gigs, a white-collar class of workers emerged from this new economy — bookkeepers, brokers, middle management, professionals, teachers and much more — and they made the most of it.

Because the new middle classes had more time on their hands, this new society championed all sorts of new activities. Concert halls and theaters were being built in every neighborhood, shops and stores abounded, especially downtown, and people young and old were going to the new parks and enjoying the outdoors. Winter brings cold temperatures, treasured holidays, and winter sports. I’ve written often about Brooklyn’s charitable giving during the holidays, as well as treasured holiday traditions, but not much about the many sports Brooklyn’s citizens enjoyed during the winter.

Skating’s long tradition

Nothing says “winter sports” in an urban setting more than ice skating. Of course, ice skating is almost as old as civilization in countries that have a cold winter climate. The first people to ice skate so far as we know were Scandinavians and Eastern Europeans who strapped the shank or rib bones of oxen, elk, caribou, and other animals to their feet over 4,000 years ago. Skates were used as a means of transportation then, not recreation. Skaters pulled themselves across the ice with sticks, in much the same way as a pole is used in skiing.

Records show that during the Middle Ages the Dutch skated on the canals of Holland. Holland is the country most associated with speed skating because the canals froze solid and were straight and long, connecting towns together. The word “skate” comes from the Dutch word schaats, which means leg or shank bone. Historical mentions of skating in countries such as Russia, Germany, and Great Britain date back to the 1600s.

Here in North America, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) used ice skates as well as snowshoes to get around in the winter. There is also evidence that the Inuit people of Alaska ice skated. Westerners first witnessed First Nations people on skates in the early 1600s and observed them playing an early game on the ice. The Iroquois called the game “hoghee” which translates to “it hurts.”

Wooden blades were in use in Europe in the Middle Ages, and the first metal blades were introduced by the Dutch in the late 1500s. It is speculated that the Scots brought iron blade skating to North Americans in Canada in the 1700s.

The first skating club in North America was the Philadelphia Skating and Humane Society Club. Since it was quite common for someone to fall through lake or river ice, every skater wore little wooden reels on their left wrist wound with strong thin rope and were trained to resuscitate a drowning victim. Rescue was the “humane” part of the club’s agenda.

Here in Brooklyn, those who wanted to skate worried very little about falling into freezing water, as most of Brooklyn’s ice skating took place on shallow ponds that were created especially for the sport. Brooklyn’s earliest baseball fields were the first public skating ponds in the city. Organized skating began during the Civil War years. The winters were much colder then, and the city’s skating ponds were filled around December 1st. It took only one cold night and a “killing frost” for them to freeze. At that time, flags with a red ball were flown at every pond, signaling that the ice was ready. It was time for everybody — male, female, young, and old — to make their way to one of the ponds. Skating was regarded as a respectable sport for everyone.

Bedford’s Capitoline Grounds

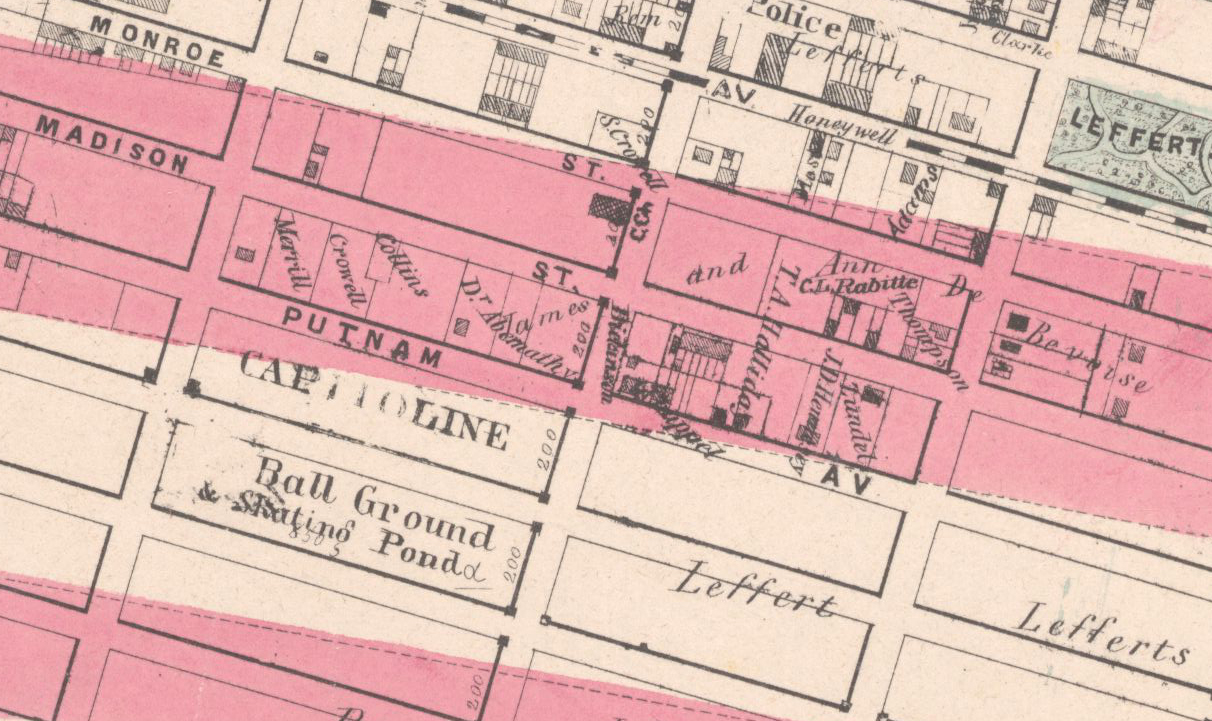

The most popular skating pond was the Capitoline Grounds in Bedford. Like many of the other ponds, the Capitoline was a baseball field during the spring and summer. It was centered between Nostrand and Marcy avenues, spanning what would become Jefferson and Hancock streets. Like all the surrounding area, the land previously belonged to the Lefferts family. Capitoline was only a few blocks away from the Lefferts family mansion.

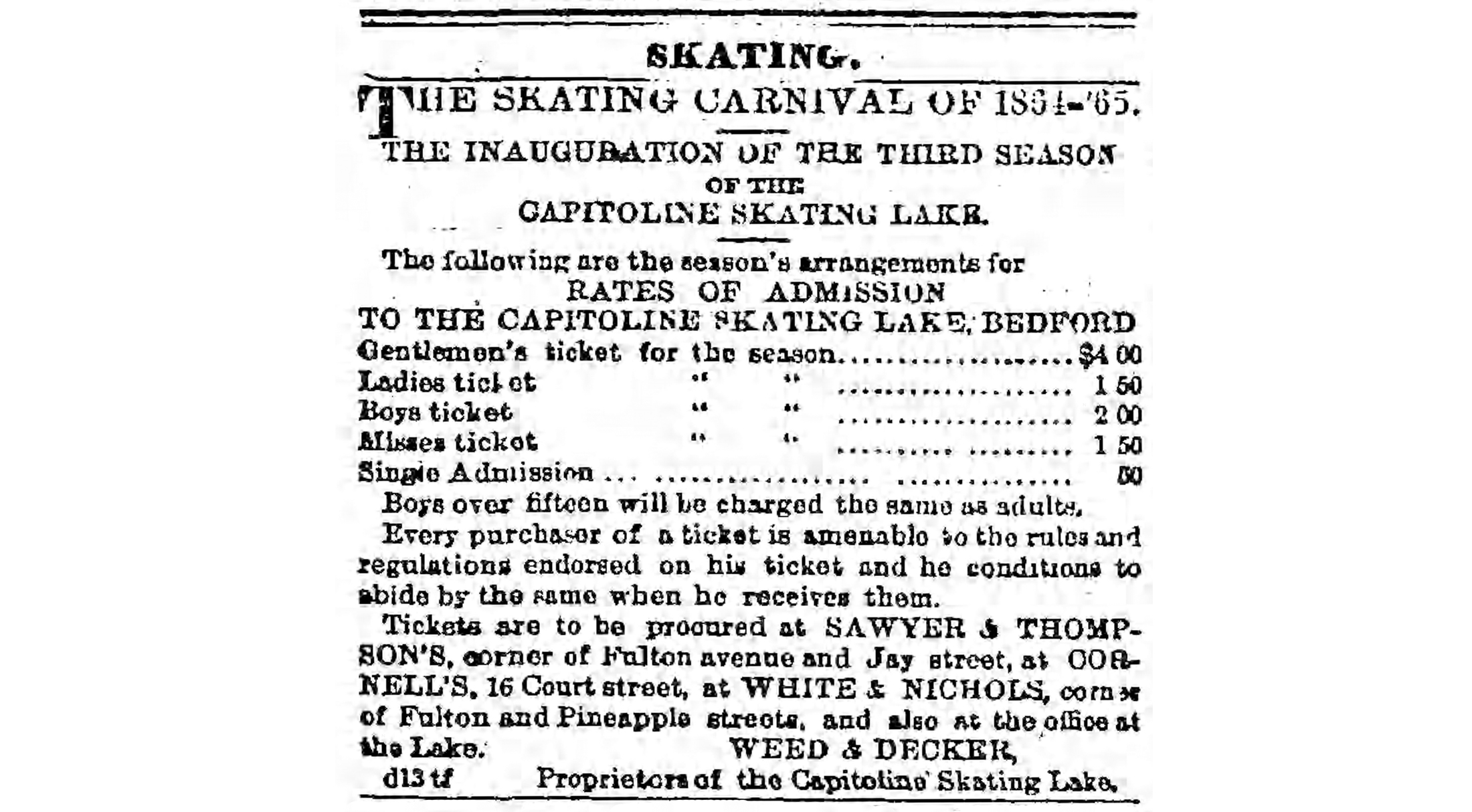

The first baseball games here were played in 1856, when it was simply a field, but a clubhouse and other amenities were in place by 1862 when the Capitoline Skating Club was established. The ground was excavated down 2 feet and a 10-foot fence surrounded the pond. The water main running under nearby Nostrand Avenue filled the pond, the water purchased by the families running the establishment. The owners were two men named Weed and Decker. Both were neighborhood property owners.

A large clubhouse was built along Putnam Avenue at Nostrand, with adjoining barns, sheds, and other outbuildings. The first floor of the clubhouse held meeting rooms for the skating clubs, storerooms and lockers, and a restaurant that was famous for its oyster stews, coffee, and cookies. The club did not serve alcohol or allow others to bring it on the premises, not even for private parties.

The second floor of the clubhouse had a large glass front that looked out over the pond. One room was made into a ladies’ parlor, while others were shared by the skating clubs. On warmer days, an enclosed outdoor patio on the second floor was reserved for the band, and space was available for the musicians inside when the band accompanied indoor dancing. The rooms were heated by coal stoves and lighted by kerosene chandeliers, later replaced by gaslight.

As the facilities were being built, many skeptics doubted that the endeavor would work, as they didn’t think the pond would retain water. But it did, and over 2,000 people were on the ice the first day. Membership in a club was required, and the Capitoline became the largest and most popular skating venue in Brooklyn. As the years passed, the venue added exterior lighting, iceboat racing, and special costumed carnivals on ice to the mix, keeping the crowds coming for 18 years.

The Capitoline Grounds has a rich history of baseball, circuses, and even a transcontinental balloon launch before the land became part of the brownstone fabric of Bedford. Hancock Street and Jefferson Avenue sandwiched the Grounds, but as brownstone Bedford grew, the Grounds were developed as row house blocks beginning in 1880. Today, the history of the Capitoline Grounds is just being explored. More will be written on this topic soon.

Smaller Ponds

“The Cap” didn’t have the only skating in Brooklyn. Many of the city’s neighborhoods had their own local ice skating ponds. The Union skating pond was in Williamsburg near the 47th Regiment Armory. It took up the two square blocks between Rutledge and Lynch streets and Harrison and Marcy avenues. It operated from the 1860s up until 1875. During the summer months, it too was a ballpark. The Brooklyn Mutuals and the Eckfords played their games there, and the park was also used for lacrosse and track and field events. All that activity was great, but for many the winter sports were the best.

The owner of the establishment was William Cammeyer, known to everyone as Cap Cammeyer. His office was at the edge of the premises. Skaters paid and entered next to the office and walked down a long flight of wooden stairs leading to a large, warm, ventilated room. Three large stoves heated the air and made a comfortable place to put on skates. The room also had a small restaurant serving hot drinks and cakes and cookies. The skaters exited this main room onto an outside platform that led to the ice.

A brass band played waltzes and marches in the evenings as skaters twirled under lights from a multitude of lamps and reflective surfaces. Cap Cammeyer enjoyed having special carnival nights, which drew the largest crowds. Costumes were encouraged but masks were prohibited. Those who were there said the colorful costumes worn by both sexes circling the ice made the evening like looking through a giant kaleidoscope. It was a most festive atmosphere and felt as if everyone in Williamsburg was there.

If they weren’t there and still in Williamsburg, people also skated in a much smaller pond near the Union, called Satellite Pond. It wasn’t as fancy as the others, but still provided fun for all. Yet another pond called Ash Pond was frequented by the poorer classes. The pond was not enclosed and was free but did not have a warm waiting room or any music.

Park Slope’s Washington Pond

Park Slope’s Washington Pond was as large as the Capitoline Grounds. Also known as Washington Park, it too was a baseball field during the summer months, one as famous as the Capitoline for the baseball fans that gathered on 5th Avenue between 3rd and 4th streets. The pond had its ups and downs in terms of facilities and the quality of the ice. It was run by several owners, and a few were less than stellar in making it a first-class rink. An article in the Brooklyn Eagle in 1867 described a pond that was not at its best, but was in the process of being improved, with new amenities and smoother ice.

Smooth ice was a requisite for any good pond. It was important not to have lumps and bumps in the ice that could trip up skaters and cause injuries. Ground crews in all the upscale skating parks kept the ice smooth with controlled melting, refreezing, and scraping.

Late 19th century skaters had many other ponds, most small, official and unofficial, throughout the city. People also skated on the lake at Prospect Park, which was much deeper and more dangerous than the ballpark skating ponds. The lake was newly built in the early 1870s, so many of the amenities enjoyed by members of the Capitoline Grounds and Washington Pond were not established until much later. People continued to favor the most established ponds.

Sports on Ice

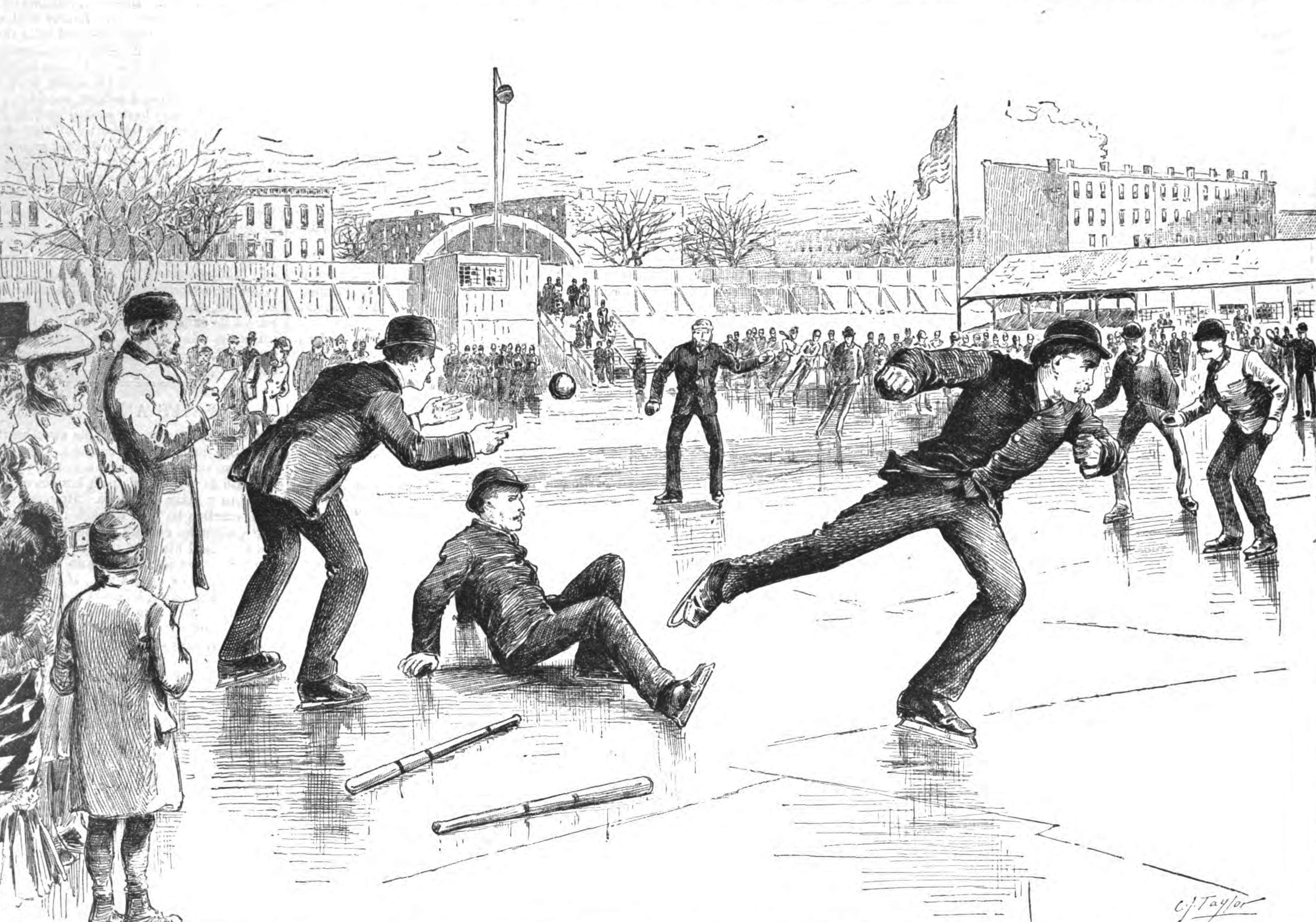

Ice skating wasn’t the only sport played at the Capitoline and elsewhere. Washington Pond was the site of the first ice baseball games, a sport that had a short life. Team players on skates played baseball. It didn’t catch on, especially where spectators were forced to stand out in the cold to watch them play.

Curling had a run of popularity. This Canadian game involves sending a heavy polished granite ball called the stone or the rock sliding down the ice towards a goal. It’s a lot like shuffleboard, on ice! Players called “beaters” sweep in front of the stone, creating friction that causes a more controlled passage down the rink.

Some ponds were large and deep enough for demonstrations of ice boat sailing, and many of the posh athletic clubs, like the Crescent Athletic Club, were enjoying a new sport called “hockey,” based on the Native American sport. Amateur hockey leagues were set up and spectators watched their hometown or college teams swing sticks and run each other down.

While hockey, first referred to as “ice polo,” was popular among young college-age men, everyone else, especially the ladies, was enjoying the talents of the professional speed and trick skaters who descended on Brooklyn as soon as they heard about the various ice rinks.

Crowds gathered to watch speed skaters race and graceful ice skaters dance around the ponds. Everyone, male and female, wanted to be them. The professionals could skate backwards, twirl, and jump — all the precursors of modern figure skating feats that have thrilled people for generations. Some of them became well-known stars who made the rounds in cities with cold climates and ice skating ponds.

One aspect of ice skating that didn’t catch on during the late 19th century was the indoor ice skating rink. Several indoor ice rinks were established, including one at the Clermont Rink in Clinton Hill. But it proved to be too difficult to maintain the correct temperatures for the ice, and the technology for creating artificial ice just wasn’t there yet. The rinks were very successful in promoting the sports of roller skating and indoor bicycle racing, but it would take several decades for the indoor ice rink to make its return.

The winter image of women and girls with their long skirts swirling around behind them and petticoats showing as they skate with their partners, friends, and children is an enduring one. The men and boys have scarves wrapped tightly around their necks, holding onto caps, top hats, and bowlers, while children fearlessly skate around the pond with wild abandon. It’s a winter holiday image that is part of American culture. It was a reality in Brooklyn, in places now only remembered as illustrations. It must have been fun!

Related Stories

- A Quick History of the Dining Room and Its Decoration in Brooklyn and Beyond

- ‘I Only Do Big Things’: Woman, Architect, and Brooklynite Fay Kellogg

- Rene Chambellan, Art Deco Architecture’s Master Sculptor, in Brooklyn and Beyond

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment