How the Jehovah’s Witnesses Acquired Some of Brooklyn’s Most Insanely Valuable Properties

Read Part 1 of this story. The Jehovah’s Witnesses — aka the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society — first came to Brooklyn in 1908, in hopes of having their sermons syndicated in newspapers alongside the writings of the borough’s most famous pastors. It was under the Watchtower’s autocratic second leader, Joseph F. Rutherford, that the religious…

Read Part 1 of this story.

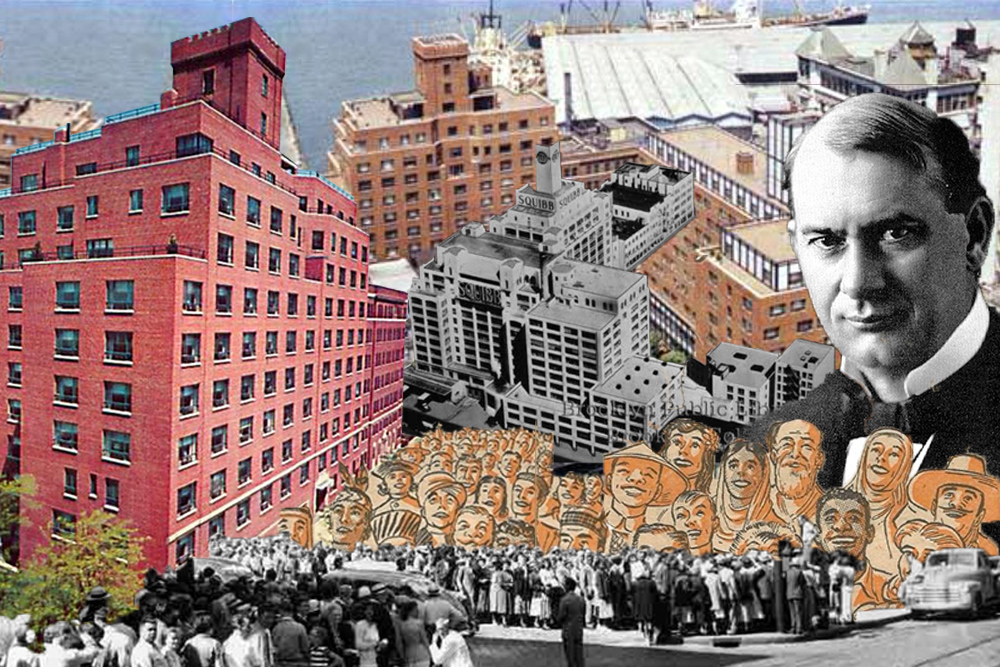

The Jehovah’s Witnesses — aka the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society — first came to Brooklyn in 1908, in hopes of having their sermons syndicated in newspapers alongside the writings of the borough’s most famous pastors. It was under the Watchtower’s autocratic second leader, Joseph F. Rutherford, that the religious group truly began practicing the art of Brooklyn real estate.

This is the 100-year story of how the Jehovah’s Witnesses grew to be a global phenomenon and came to own some of Brooklyn’s most valuable properties.

Joseph Rutherford, the Uncompromising Leader and Brilliant Propagandist

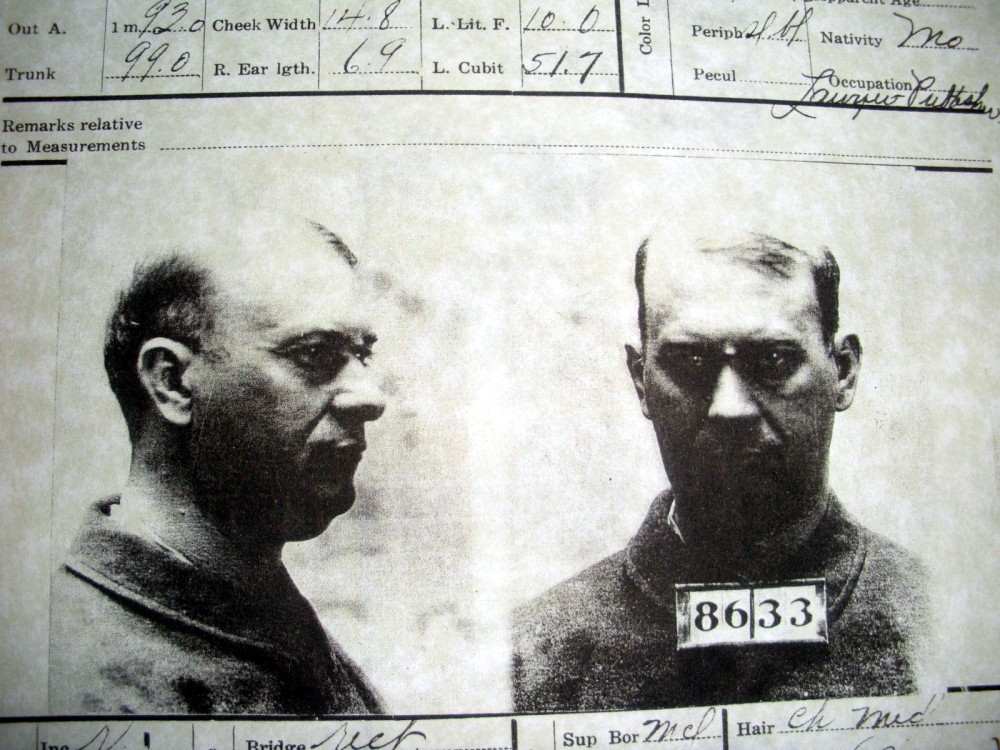

Joseph Rutherford was voted into office by the governing body of the Society, but he was dictatorial and autocratic — not the leader the Watchtower directors had imagined.

He angered many with his beliefs that faith should come before patriotism — a big no-no for the time, as World War I was raging halfway around the world. In May of 1918, the U.S. Attorney General called his writings and lectures “one of the most dangerous examples of propaganda” ever written, and his works were banned in Canada.

Rutherford claimed that 1918 was the year God was coming to claim his kingdom, and that the governments of the world and their “unrighteous” religions would come to an end.

A Little Legal Trouble for the Witnesses

Rutherford and seven other Watchtower executives were arrested and charged under the 1917 Espionage Act for insubordination, disloyalty, refusal of duty in the armed services, and obstructing recruitment and enlistment. Seven men — including Rutherford — were sentenced to 20 years in prison.

The Society sold the Brooklyn Tabernacle building on Hicks Street, as well as the office furniture out of their main headquarters — Bethel — on Columbia Heights. The Society still owned the building, they told the press, but were likely to sell it “any day.”

The Brooklyn Eagle rejoiced, and a Watchtower member was quoted as saying, “I blame the Eagle for all of our troubles. It first attacked us years ago and never has ceased.”

But the Eagle crowed too soon.

In March of 1919, the Watchtower men were all released on bail, and the charges were dropped a year later. Rutherford had been re-elected as the head of the Society, and they were not going anywhere.

The Worldwide Growth of the Jehovah’s Witnesses

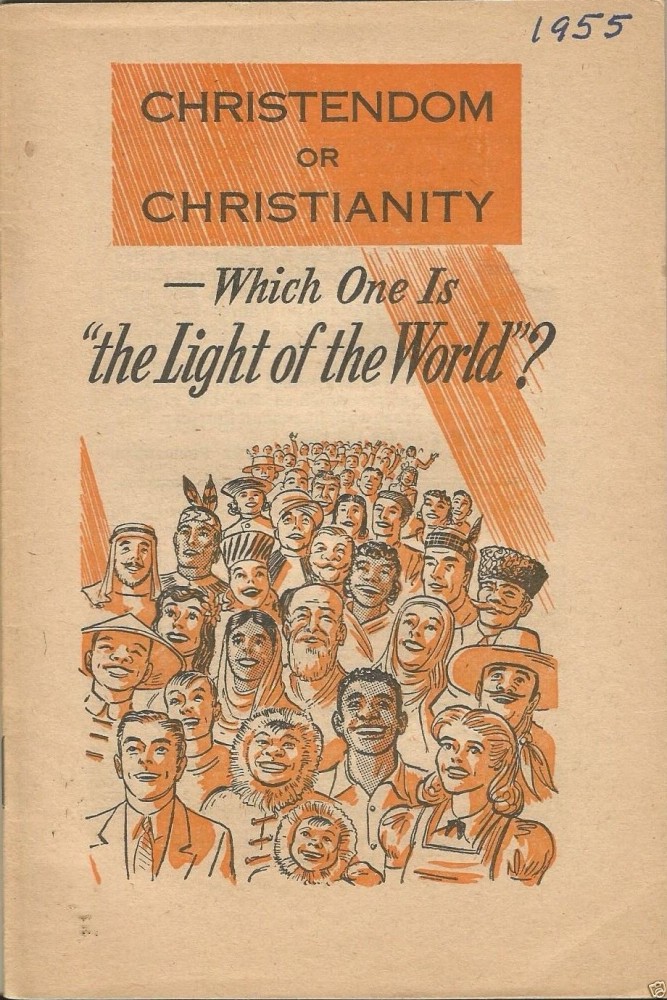

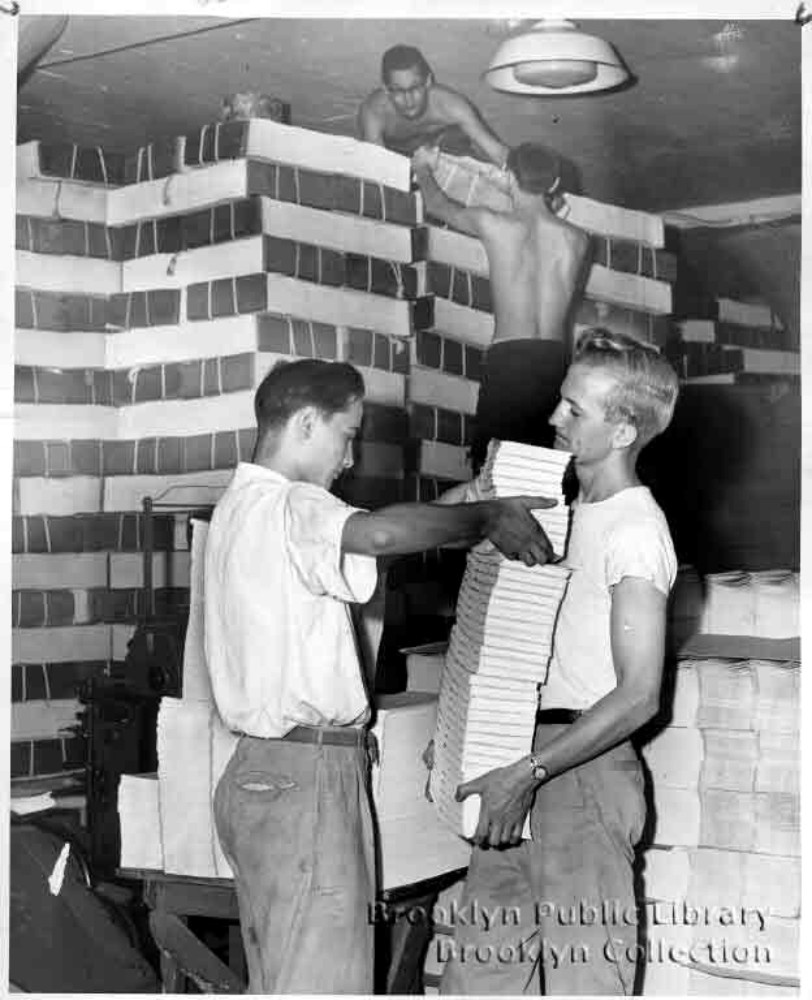

Between 1920 and Rutherford’s death in 1942, the organization grew to include millions of followers worldwide. This success and the Witnesses’ emphasis on studying printed materials — in 100 languages — meant that they needed to expand their Brooklyn operations dramatically.

Even in the very beginning, the Society relied on volunteers to operate the presses and staff shipping rooms. These volunteers dedicated years to their work and were paid only pennies, while living in dormitories and group housing. The Eagle saw this as a sure sign of cult behavior even in 1910.

Although the Watchtower Society looked like the organization Charles Russell began, the Rutherford years changed almost everything they believed in. He changed their name to Jehovah’s Witnesses in 1931 to differentiate them from the remaining Russellites — although the legal name remains the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society.

He was also responsible for the group’s practices that are frequently compared to cult behavior, including the shunning of holidays and birthdays, the banning of singing at services, and the requirement and sacred duty of door-to-door visits.

And the group continued to grow.

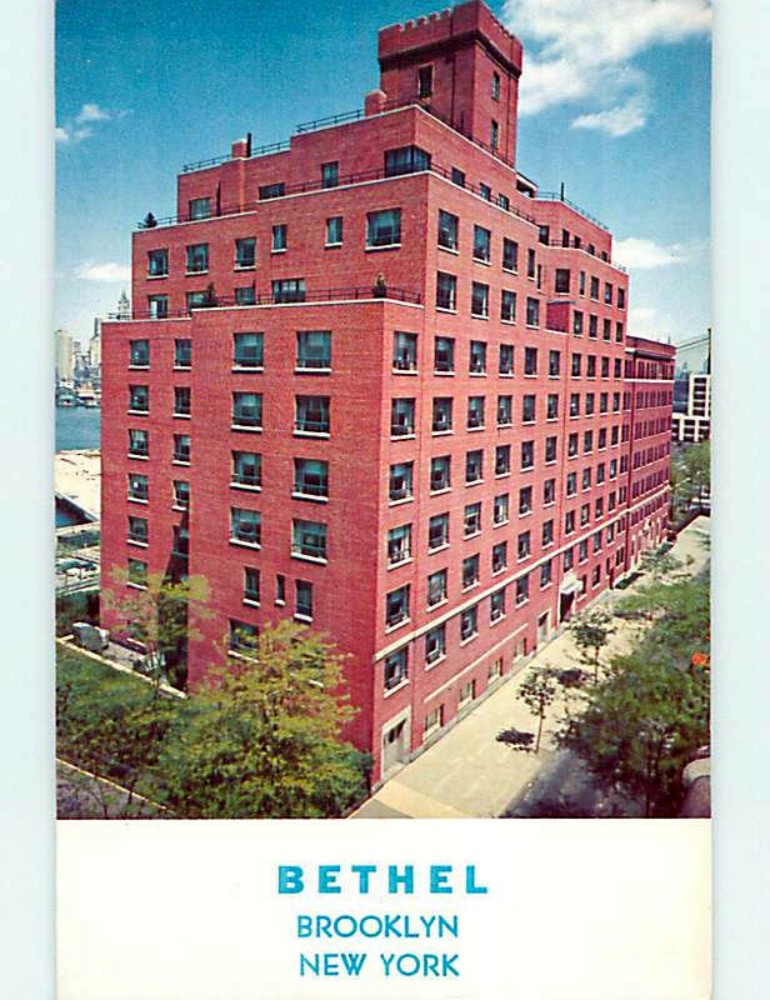

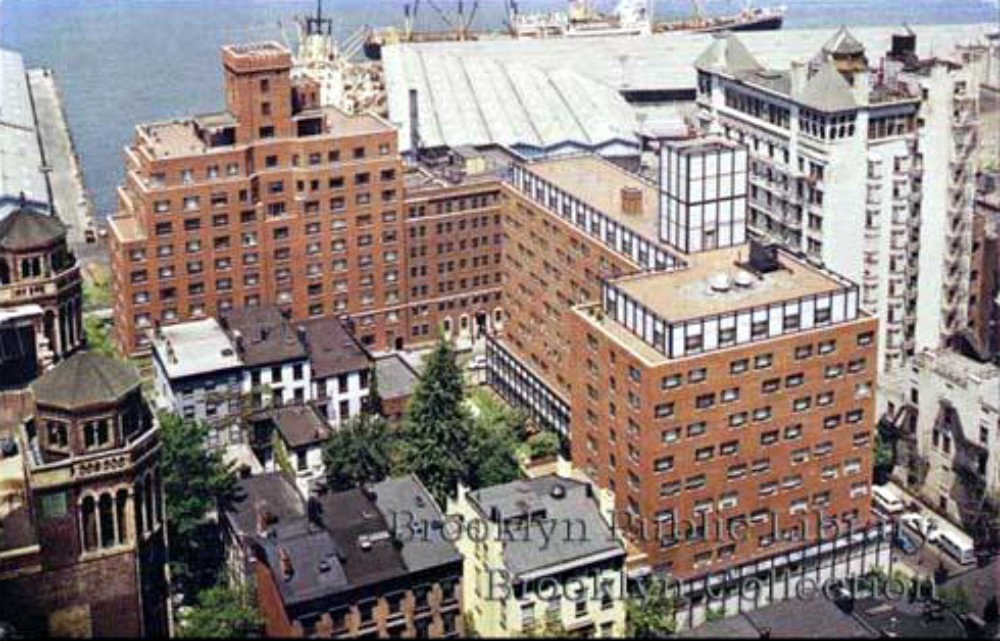

In 1927, the Watchtower had just finished a new printing plant at 117 Adams Street, the Eagle noted. The Society was tearing down the old Beecher house at 124 Columbia Heights, as well as the surrounding buildings and was building a new nine-story dormitory and headquarters on the large site. This would be the new Bethel world headquarters.

Rutherford was still bitter about his incarceration by the government, and instructed Witnesses to never bend a knee to a worldly government, serve in the armed forces or salute a flag. In the 1930s and ’40s, the Witnesses would be in court for years over both issues and eventually won, changing constitutional law regarding freedom of religion.

Joseph Rutherford died of colon cancer at his luxurious home called Beth Sarim, in San Diego, on January 8, 1942, at 72 years old. He was replaced as president by Nathan H. Knorr.

By 1950, the Witnesses, still growing, purchased a large block of land in Dumbo that included several tenement buildings as well as factory space. They planned to relocate the residents before tearing everything down for a huge new factory.

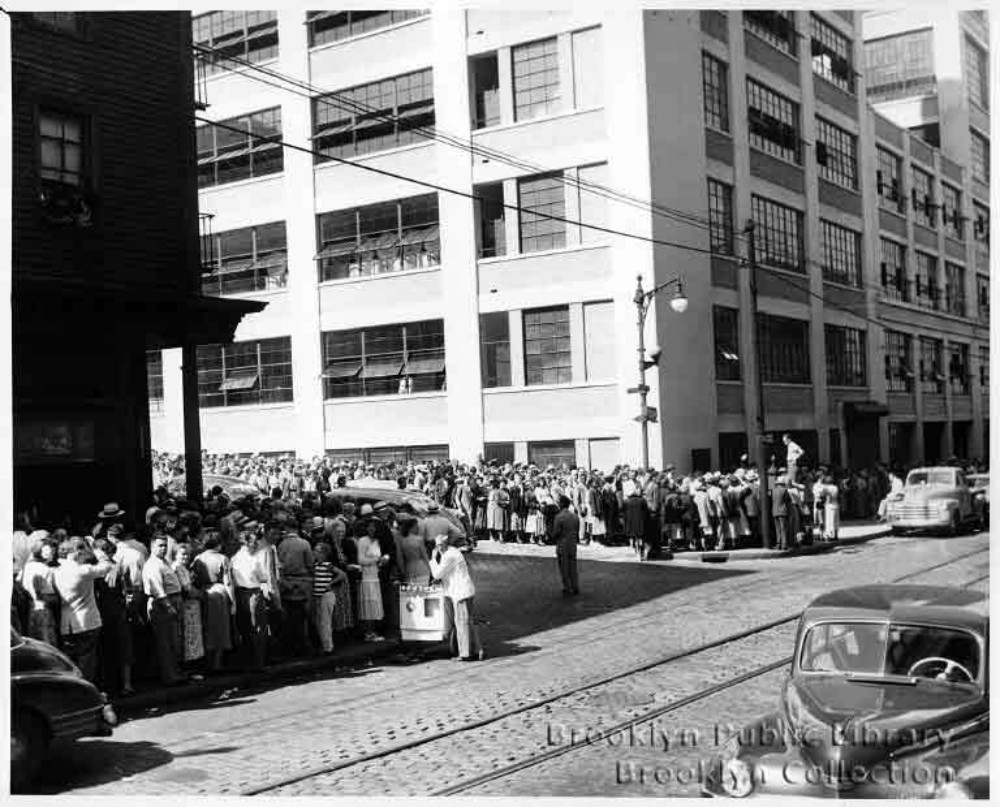

The annual Witnesses’ Convention of 1953 included a tour of this new building. Thousands of people lined the streets from the Heights down to Dumbo, all eager to see the new printing presses.

In 1969, they acquired an even larger complex of buildings — the former Squibb pharmaceutical plant just down the street from the Bethel HQ. The number of volunteers living in the Bethel headquarters had grown to more than 1,300 people, and the organization also needed somewhere to store the paper for their massive printing operation.

For the majority of the 20th century, the Witnesses continued to grow and quietly buy up surrounding real estate. They purchased some of largest buildings in the Heights and Dumbo, including the Leverich Towers, the Bossert Hotel, the Standish Arms and a score of smaller buildings. After the Hotel Margaret burned down in the 1990s, they built another large residence on the site.

Although some Heights residents did not particularly like the masses of Witnesses walking to work, or knocking on their doors, or not paying property taxes, most people had to admit that they were excellent stewards of their properties.

The Witnesses had not been in favor of the landmarking of Brooklyn Heights in 1965, but after it went through, they complied with all of the rules. While most of their Brooklyn Heights holdings are within the landmark district, the large Squibb buildings on Columbia Street lie just outside of the designation area.

Detractors — from the Eagle’s editorials in 1911 to the present — have always said, “If the Kingdom was coming any day, why not rent? Why buy all of this valuable real estate?”

The Witnesses Begin Moving Out of Brooklyn

More than a century after Charles Russell set up the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society in Brooklyn, the Witnesses decided it was time to move their operation somewhere with more expansion potential. They purchased a 250-acre forested plot in Warwick, N.Y., and in 2011 began liquidating their Brooklyn Heights holdings piece by piece. Even the Bethel headquarters is for sale.

Estimates put the value of all their remaining properties at well over $1 billion. The full-block site at 85 Jay Street in Dumbo is particularly attractive to developers.

With the Witnesses leaving Brooklyn Heights, they’re also leaving behind a rich local legacy. Though members of the organization weren’t always welcomed with open arms, the Jehovah’s Witnesses have had an undeniable impact on the Brooklyn of today. And their exodus with undoubtedly shape the Brooklyn of tomorrow.

Related Stories

Suzanne Spellen, aka Montrose Morris, Is Writing Brownstoner’s First Book

The End of the World: Charles T. Russell and Why the Jehovah’s Witnesses Came to Brooklyn

Reader Unearths Extraordinary 1969 Letter About Then-New Jehovah’s Witnesses HQ

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

[sc:mailchimp-books ]

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment