A Day of Remembrance and Celebration: The History of Memorial Day in Brooklyn

We normally celebrate Memorial Day with food, festivities and perhaps even a day at the beach, on the semi-official start of the summer season.

Photo by Susan De Vries

Editors note: This post originally ran in 2013 and has been updated. You can read the previous post here.

We celebrate Memorial Day with food, festivities, and perhaps even a day at the beach, on the semi-official start of the summer season. Some of us plan to go shopping, taking advantage of the Memorial Day sales at practically every large department and discount store.

Because the experience of war, losing someone in war, military service, or even having a relative in the service is so foreign to most of us nowadays, it’s hard to conceive of this convenient holiday on the last Monday in May being anything more than just a blessed day off, a break in the schedule of hard work with which we are all too familiar.

But it was not always so.

My parent’s generation were veterans of World War II, with the Korean War following right on its heels, so war and national and personal sacrifice were things they were very familiar with. I grew up in a small town upstate where patriotic parades took place on Memorial Day, the Fourth of July and Veterans Day, with the school band marching down the village streets, followed by the local chapter of the American Legion, the Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, the 4-H, the Grange, church groups, and anyone else who wanted to participate.

Looking back, I’m surprised there was anyone left to line the streets, but there was always a crowd, waving flags and cheering. I started out marching with the Girl Scouts, and by high school was in the marching band, along with my brother. My Dad, a WWII vet, marched with the American Legion.

Our parade began at the school, wound through the town, and ended at the village cemetery, where a very solemn ceremony of wreath laying took place, accompanied by prayer and a 21-gun salute fired by proud veterans. It ended with the lonely and poignant sound of taps echoing across the hills. My brother was one of the two trumpet players on opposite sides of the cemetery, one playing the echo to the other.

The Vietnam War was still dragging on, but on that hill above Gilbertsville, time stood still, the ground was sacred, and even as a rebellious generation, we knew and honored those traditions.

It was as American as you could get, in a village cemetery high on a hill above the town, with lilacs in bloom, our band uniforms hot and uncomfortable from marching up the steep hill, surrounded by the graves of townspeople, dating back not only from the time of the 20th century’s wars, but as far back as the Civil War, even back to the Revolutionary War.

It was an old and storied place, a fitting place for a holiday that began as “Decoration Day,” to honor the Civil War dead.

Laying flowers on the graves of soldiers lost in battle has been an old tradition in America. The Civil War, in which men died by the thousands on American soil, some close to their own homes and families, made that tradition even stronger.

It became the duty of women — the wives, mothers, sisters and relatives of the dead — to gather up fresh flowers and decorate the graves, honoring with beautiful blossoms and scents the dead who perished horribly in a war on American soil, pitting brother against brother. The practice began before the war was even over, with the memorial cemetery at Gettysburg established in 1864.

There were memorial celebrations in cities both north and south by war’s end. The Civil War cost so many lives, over 600,000 in total, that the federal government began establishing military cemeteries in 1865, initially only for the Union dead. Arlington Cemetery dates from this time.

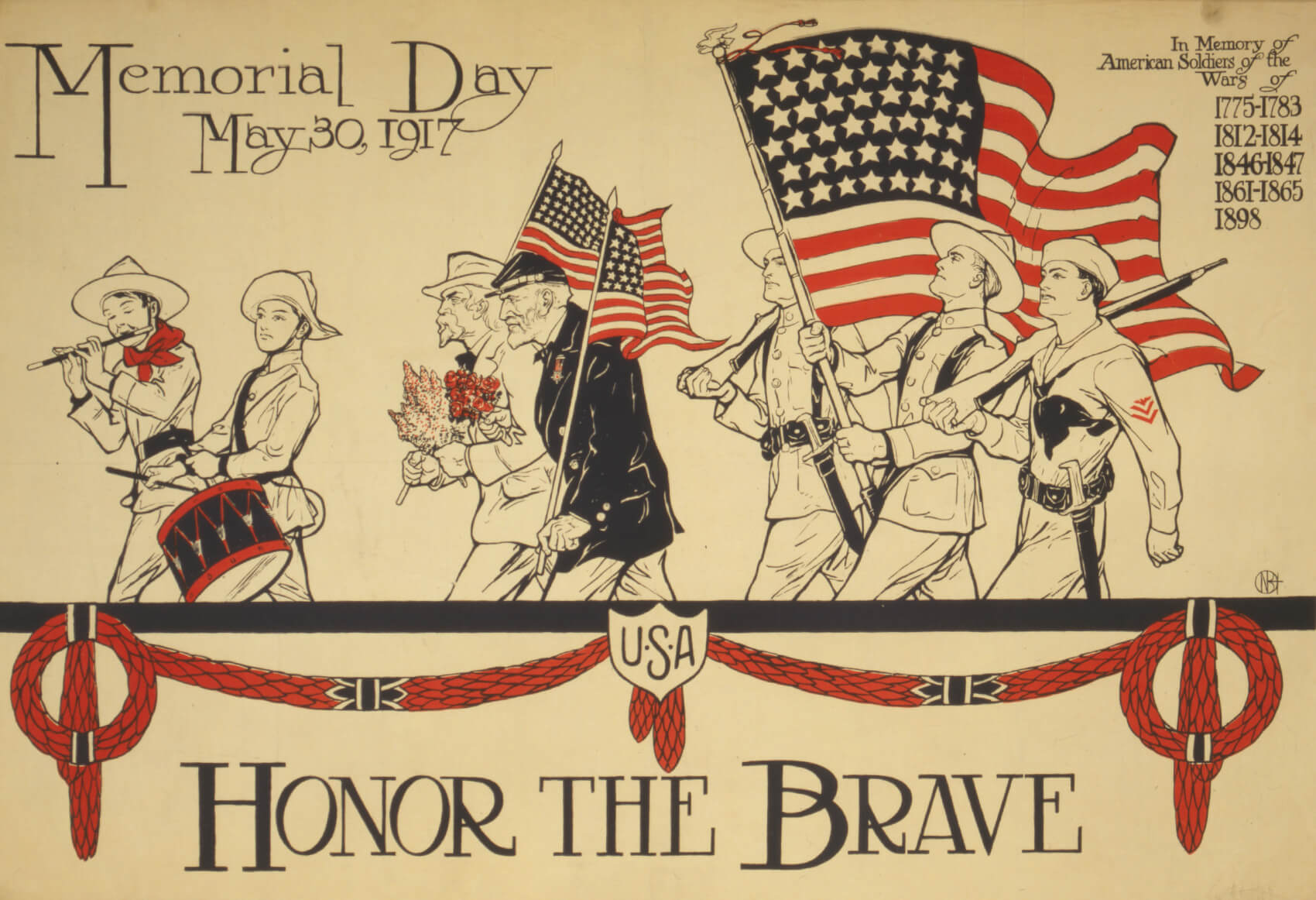

In 1868, General John A. Logan, the commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), the Union Army’s Veteran’s Association, instituted the first “Decoration Day,” calling for it to be celebrated in cities and towns across the country. The date May 30th was chosen at random, coinciding with the optimal time of year for flowers to be in bloom. By 1890, every northern state had declared the day a holiday, with many of the southern states following suit.

The name “Memorial Day” started to be used in 1882, and gradually replaced “Decoration Day” as the name of the holiday, although it was not the official name until 1967. In 1968, Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, which made four holidays, including Memorial Day, on a Monday, in order to create a three-day weekend.

Memorial Day became the last Monday in May, no matter what the date. The Act did not take effect until 1971, although it took several years for all of the states to comply with the new rules, which they all eventually did.

Many people thought this move trivialized the holiday, making it more about sales and summer, rather than commemorating our country’s war dead and the sacrifices of our military personnel and their families. Senator Daniel Inouye of Hawaii, a World War II veteran, introduced a measure to return Memorial Day to May 30 every year from 1987 until his death in 2012.

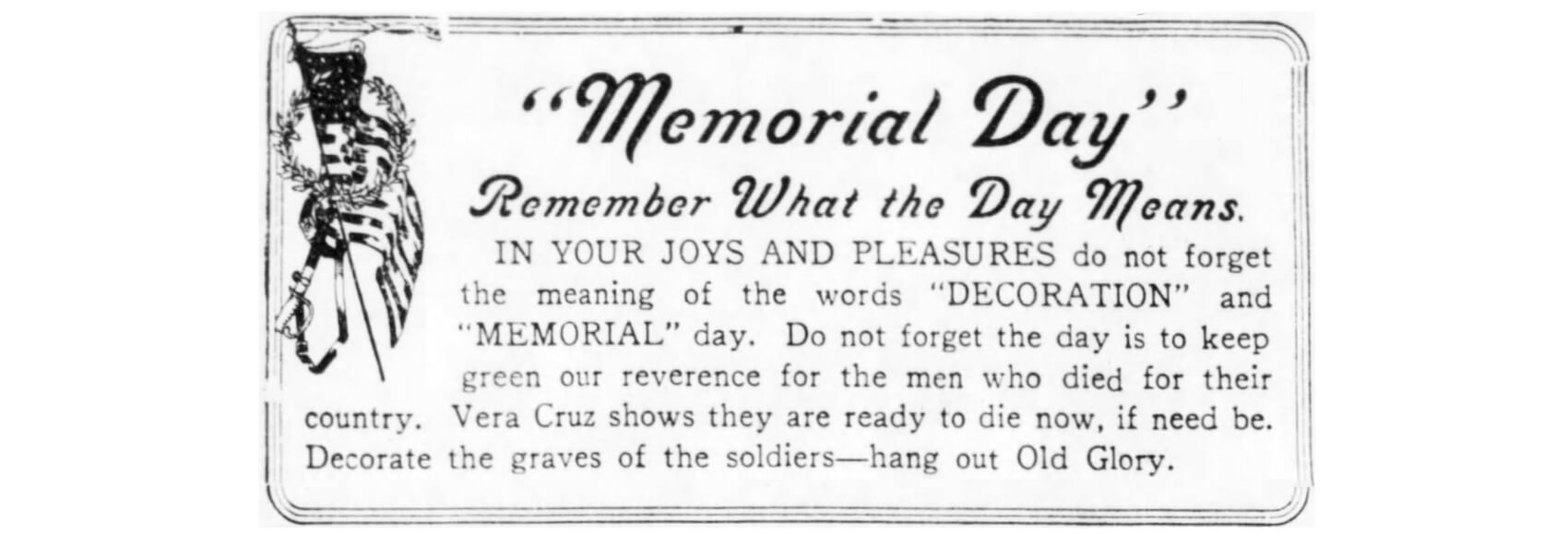

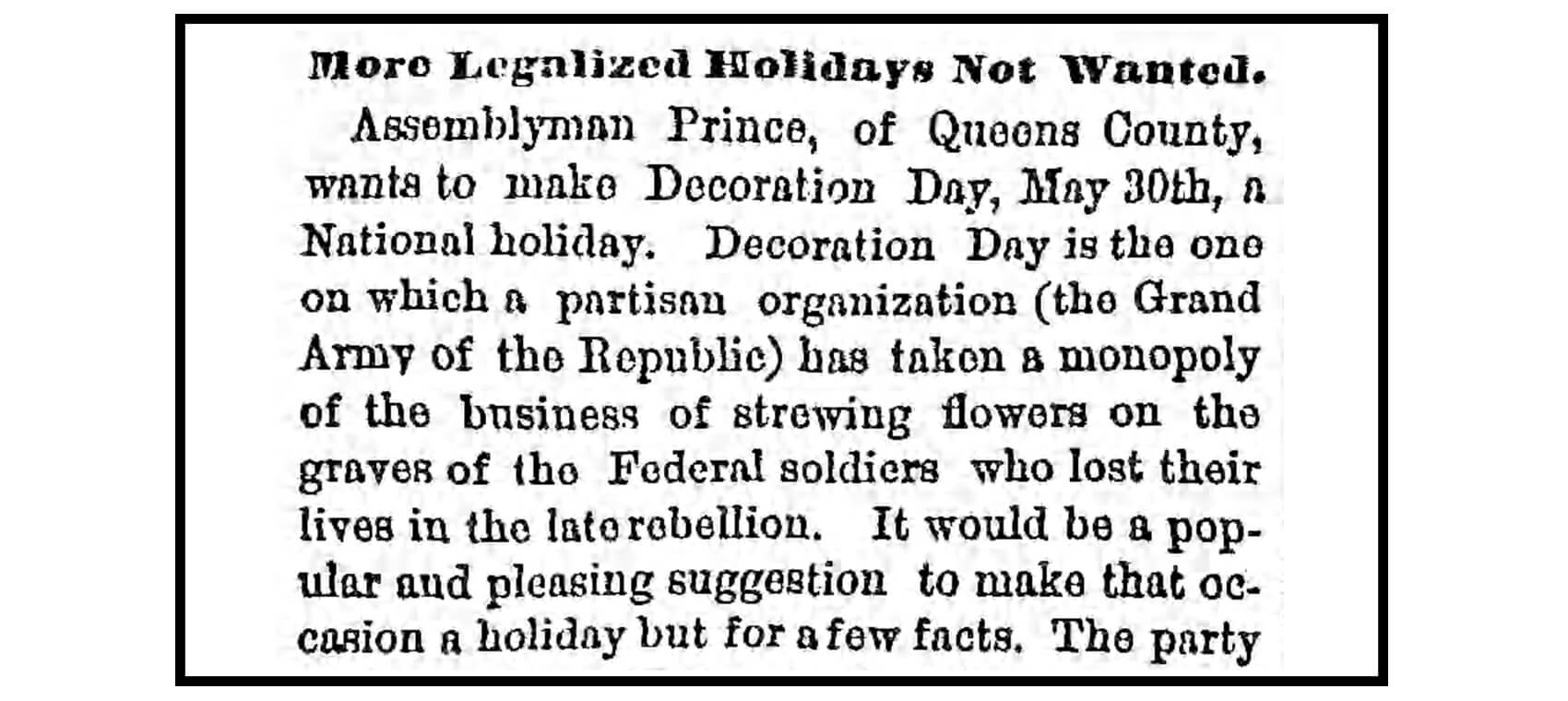

He would have been liked by the editorial writer of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle who wrote an essay on Decoration Day way back in 1871. The unknown writer was complaining about an effort by a Queens assemblyman named Prince who wanted to have Decoration Day declared a national holiday. This writer wasn’t having it.

Since Decoration Day was an establishment of the GAR, that meant that it was an establishment of the Republican Party. The Eagle writer didn’t like the partisan politics of the holiday, or what he saw as a continuation of the war. In 1871, the war had been over for only six years, and was still fresh on the national memory, yet now was being fought in the graveyards.

He explained: “Decoration Day is the one on which a partisan organization (the Grand Army of the Republic) has taken a monopoly of the business of strewing flowers on the graves of the Federal soldiers who lost their lives in the rebellion.” He went on to complain that that’s all well and good, but it’s supposed to be a FEDERAL holiday, which includes both North and South.

“Now there were two sets of soldiers; Northern and Southern, but both American. They fought with a gallantry that each acknowledged and respected. On thousands of fields, they lie side by side. Sincere and sympathetic attempts to decorate Confederate graves have been repelled by bayonets and greeted with contumely and outrage,” he wrote.

“This has been the case every year at Arlington and other cemeteries. A holiday could not of course, be as bitter to one section as it might be agreeable to another, under such circumstances. The custom now is to have Northern graves decorated at one time and Southern graves another. This will perpetuate separate observances and eternalize feuds even over the tombs of the peaceful dead,” he warned.

In addition to the sectarian separation — he certainly had a point there — he also railed against declaring a holiday on which people were supposed to not celebrate, but spend the day in mourning and in cemeteries. He felt that went against the American spirit.

He also just didn’t like government mandated holidays. “It is against the instinct of a free country to multiply national days. The few we have are certainly sufficient,” he said. He cited European holiday traditions, and then added, “While the people play, their tyrants forge chains for them, and exact from the very time they allow imposts that make the period a treble loss.”

Decoration Day in Brooklyn became a popular holiday, with parades and solemn visitations to cemeteries for commemorative services. Civil War veterans were a part of Brooklyn life through the early part of the 20th century; the last few veterans died of extreme old age in the 1950s. They had been drummer boys and child soldiers in the war.

Although Green-Wood Cemetery was the resting place of many of Brooklyn’s wealthiest people, it was also a large resting place for the Civil War dead. During the war, in 1862, the cemetery instituted a free veteran’s burial ground, called the “Soldiers’ Lot.” Today, after careful research, it has been determined that there are over 3,300 Civil War soldiers buried there and elsewhere in the cemetery.

The Civil War Soldiers’ Monument was dedicated by the City of New York to its Civil War dead, and was built in 1869, only four years after the end of the war. It sits on the top of Battle Hill, the highest point of the cemetery, and portrays four soldiers in uniform, at the four sides of a granite pedestal and column. The soldiers are cast in zinc, with bronze plaques on the granite base. Since the day it was dedicated, this memorial and all of the other memorials to soldiers dead from many more wars since have been places of quiet and somber reflection upon the effects of war, both good and bad.

Brooklyn has always had her Memorial Day traditions, with parades, flags, and those same solemn ceremonies at cemeteries so large my entire hometown could be set in one and there would still be room. Even here, in a noisy city, the echo of taps, resounding from hill to hill, still reminds us of the importance of the day.

Although we may not know those who have served or died, their sacrifices make our holiday possible. It is good that we remember.

Related Stories

- Catch Some Tunes at the 19th Annual Green-Wood Memorial Day Concert

- In 1897, a Tally-Ho Decoration Day Ride Went Horribly Wrong

- From War and Tragedy to Celebration: What Memorial Day Means to Brooklyn

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment