Walkabout: The Summer of 1915 — Edward Reiss and the "Negro Invasion" of Park Slope

Edward Reiss was a larger-than-life Brooklyn character in the early 20th century who often took matters into his own hands when a situation wasn’t to his liking. Our story today concerns his use of a racist power play to get his way in a feud with a developer. Reiss was the owner of the Marine Wrecking…

Edward Reiss was a larger-than-life Brooklyn character in the early 20th century who often took matters into his own hands when a situation wasn’t to his liking. Our story today concerns his use of a racist power play to get his way in a feud with a developer.

Reiss was the owner of the Marine Wrecking Company, a very successful salvage company that plied the waters around New York City and the surrounding states, towing in damaged and abandoned craft, and salvaging underwater wrecks.

His name was frequently in the papers after 1910 for his yachting activities. A member of the Park Slope Civic Association, he was one of the Slope’s most aggressive and ardent boosters. When his plans to erect a statue in the area didn’t come to fruition, he was disappointed, but by 1915 he had more immediate problems. A developer was building a six-story apartment building right next door to him.

Edward Reiss and His Neighborhood

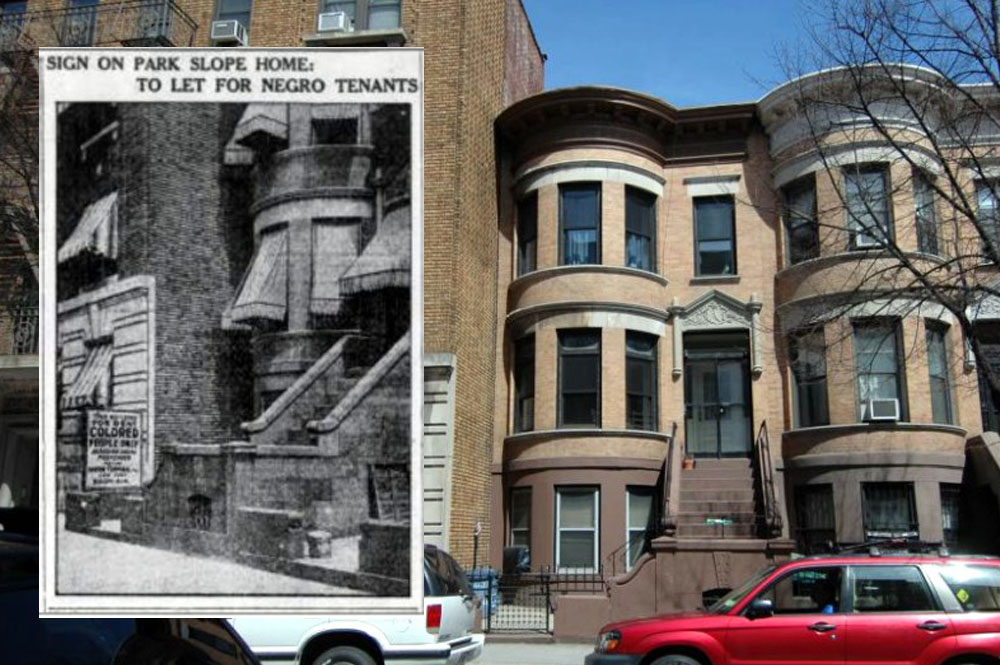

Reiss and his wife Jennie lived on the upper edges of Park Slope, in a rather modest row house at 461 15th Street. They were the first owners of this house, which was the lead in a group of four two-family houses built by architect Benjamin F. Hudson and developer Morris Levy in 1909.

The papers referred to the house as a “mansion in a highly desirable neighborhood,” which suggests Reiss may have made some serious upgrades to the home. But after four years of domestic bliss, the building became ground zero for a major feud.

Photo via Google Maps

The Great Apartment-Building War

In 1914, Walter Kraslow of the Kraslow Construction Company began building a small elevator apartment building, butting up right next to the Reiss house.

When construction first started Reiss was quite neighborly, even letting the crew use his telephone for emergencies and offering cold water to the work horses standing in wagons in front of the house. But as construction continued, the good will evaporated.

Reiss started complaining that the horses and wagons had torn up his cement sidewalk. By the spring of 1915, the building was almost finished but the carelessness was now intolerable.

According to Reiss, the workmen had damaged his roof with wet cement. They had destroyed his back fence and garden and splashed paint all over his windows and on the front of his building.

He contacted Walter Kraslow and demanded that they fixed the damages and restore his four-year-old house back to its original condition. Kraslow glossed over his concerns and did some slap-dash repairs, and tempers flared.

On an evening in June 1915, Walter Kraslow was arraigned in Brooklyn Magistrate’s Court on a charge of assault. The complainant was Edward Reiss. Only a few days before, Reiss was in the same position, having been charged with assault by Walter Kraslow. The battle was getting physical.

Tensions were very high on the block and most of the neighbors were squarely behind their neighbor, Reiss.

With the new apartment building on the verge of accepting its first tenants, Reiss brought out the big guns, the ultimate horror for any up-and-coming neighborhood in early-20th-century America — he threatened Walter Kraslow’s real estate prosperity with the presence of African-Americans.

July 27, 1915, photo via Brooklyn Eagle

The 1915 “Negro Invasion” of Park Slope

Since Kraslow wasn’t going to properly repair Reiss’s house, Reiss decided to make his neighborhood much less desirable to potential tenants. And what was worse for property values than the threat of black families moving in?

He had a large sign made up and announced that he was going to rent out his house. Not just to anyone, but exclusively to “Colored People.” The entire neighborhood was aghast.

His large sign made the newspapers — all of them, including in Manhattan. Each one of them hyped up the horror of what one called “The Negro Invasion.”

Reiss loved the attention. His sign read, “This building for rent. COLORED people only. Boarding house preferred. Inquire Hudson Terminal Building, New York, Room 414.”

His heavy metal sign was fixed to his fence, facing his house. He told the papers that he had hired a Negro band to play in front of the house that weekend.

Reiss held court with newspaper reporters, telling them that he had electrified the sign and was, in Reiss’s words, powerful enough to “shake anyone out of his shoes.” If that didn’t do it, he also hired a “250 pound Negro,” who had been ordered to keep people at a distance from the sign.

Reiss told the New York Sun that the reason he had taken these steps was because Kraslow had made the repairs, but had just slapped them together. The cement on his sidewalk was patched with three different colors of cement, and crumbled away after three weeks.

His backyard fence had been replaced with a cheap board fence that was whitewashed, and washed away in the first rain. He also said the blobs of paint and cement were still on his house and lawn.

After the two were in court accusing each other of assault, a written agreement was drawn up to cover the repairs, but a month had passed and nothing had happened. This was his last desperate move, he said.

Reiss told the paper, “I had the sign up at six o’clock this morning, and I kept watch on it with a club in my hand until one of the biggest Negroes I’ve got at the Reiss Company’s contract at Sing Sing could come down. He won’t take that sign down for anyone, not even for my wife.”

“I was warned there’d be a white-cap brigade tonight to tear it down. That’s why I hitched five electric wires of 110 volts each to it. I’ve bought another home at Ninth Street and Prospect Park West, and I’ll be moving into it soon. I don’t care what this costs me.”

But Edward Reiss Got His Way

Word soon came that Walter Kraslow had come around. He produced a bond and a guarantee to fix everything to Reiss’s liking, starting immediately. The sign came down. “I’m going to miss it,” Reiss told reporters.

The threat of a “Negro Invasion” was a mighty one indeed. This was not the only case where this happened, either. Sadly, there are more such stories for another day.

Photo by Kate Leonova for PropertyShark

Photo via Google Maps

Related Stories

Rufus L. Perry and Rufus L. Perry – Father & Son – Brooklyn Pioneers

Building of the Day: 395 Washington Avenue, the Piano Maker’s Mansion

Past and Present: Park Slope’s Plaza Hotel

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment