Past and Present: The Monastery of the Precious Blood

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. As so often happens, I was researching something else when I happened to look at this particular Sanborn insurance map of Bedford, dated 1908. There, in the middle of the block between Jefferson and Hancock, flanked by Bedford and Nostrand avenues, was a cloistered Catholic monastery. I used…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

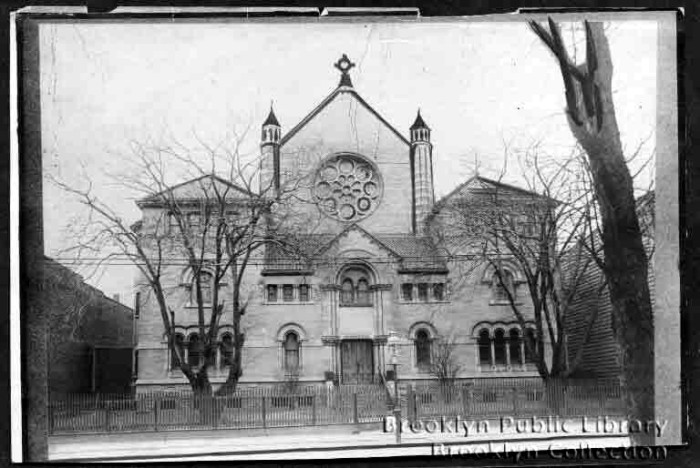

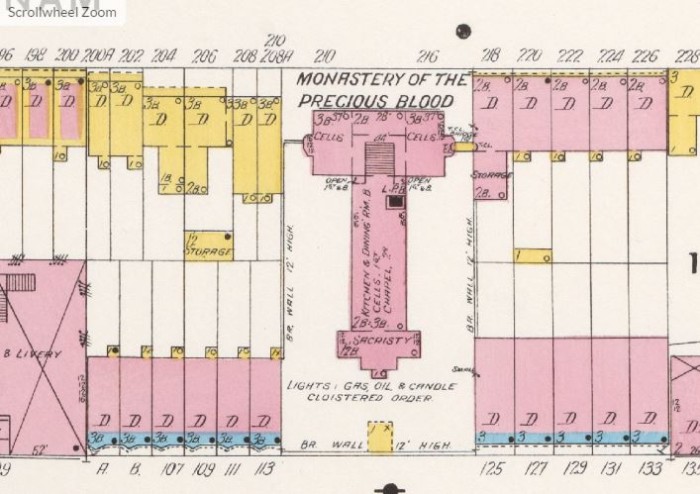

As so often happens, I was researching something else when I happened to look at this particular Sanborn insurance map of Bedford, dated 1908. There, in the middle of the block between Jefferson and Hancock, flanked by Bedford and Nostrand avenues, was a cloistered Catholic monastery. I used to live two blocks away from there, so I knew it was gone, but in all the research I’ve done on Bedford, I had never come across this building or heard of the monastery before. What was the story, and were there any photographs of it in existence? Fortunately, yes, the Brooklyn Eagle had one, which I found both in the paper itself, and the same photo also in the collection of the Brooklyn Public Library. Wow, nice church building, 10 foot walls, cloistered nuns! Who knew?

The monastery had quite a history. The order was established in Quebec in 1861, and began with four women who devoted their lives to cloistered prayer and contemplation. The order grew, and by 1887, there were four monasteries in different parts of Canada. In 1890, the order asked Bishop Laughlin of Brooklyn if a monastery could be established in this city. He gave his permission, one of his last acts before his death, and a small group of nuns moved into a small house on Sumpter Street, in what is now Ocean Hill.

The order continued to grow, and needed a larger home. With the help of devout Catholics in Brooklyn, as well as the diocese, the order was able to have this new facility built for it, here on four lots facing Putnam Avenue, with the property stretching back to Jefferson Avenue. The address was 212 Putnam Avenue. The architect chosen for the project was Rudolfe L. Daus, a prominent Brooklyn architect, a Catholic, and the architect of several other projects for the Church, including the large St. John’s Home for Boys, on St. Marks Avenue, and Our Lady of Lourdes Church. He also designed the 13th Regiment Armory, only blocks from here, the Telephone Building downtown, as well as many distinctive row houses, hospital buildings, commercial and civic buildings.

In reading up on the fundraising for the monastery, it was amazing the amount of public support they got, from Catholics and non-Catholics alike. Perhaps because they were very cloistered and humble, or because of their distinctive red habits, or even their extreme devotion to the blood and suffering of Jesus, whatever it was, they were the most popular cloistered nuns in Brooklyn.

Rudolfe Daus’ wife was the hostess and organizer for some of the fundraising activities. She and her friends held fairs and fundraising concerts, with all of the proceeds going to the building fund. Parishes all over Brooklyn held their own fundraisers or had special collections taken for the monastery, as well. Even after the building was finished, the monastery was the subject of frequent fundraisers to help support it. It needed the money, too, because most of the nuns never left the cloistered walls.

If you take a look at the map below, you can see they took cloistering seriously. The map states that a 12-foot-high brick wall surrounded the grounds on three sides; only the front of the monastery was open to the street. Over the course of their time here on Putnam Street, the order received many novitiates from Brooklyn, and it also held weekend retreats here for the faithful.

When the building was complete, the order held an open house and a bazaar, a rare thing for a cloistered order. The order wanted people to see where their money had gone, where more was needed, and to show potential nuns as well as the curious, how they would live, and what life would be behind the walls. The bazaar lasted 10 days. People could tour the facility and see the chapel, the cells where the nuns would live, as well as the dining room, community room, kitchens, reflectory, novitiate, laundry and infirmary. After the fair was over, and the building blessed and dedicated, that was it; the gates would close and lock and cloistered life for the nuns inside would begin.

On May 27, 1894, the Brooklyn Eagle had an announcement that the Monastery of the Precious Blood would be closing its doors to the public the following Wednesday. They had so many people at the bazaar and open house that they had to extend it a few days more. The gates were closed, but a year later, the chapel was finally finished, and it was opened briefly for a public mass of dedication.

Throughout the next few years, the monastery remained in the news and in the society pages. There were many different fundraisers held to support the institution, and many society ladies made it one of their favorite charities. Fundraising lectures, concerts and bazaars were held frequently, the proceeds helping the nuns in their mission. Although the grounds were cloistered, the chapel had a weekly public mass, and was sometimes used for concerts. Those who attended were used to seeing the sisters with their blood red habits, slipping silently out of their seats and then melting away back into their isolated world.

By 1908, the Monastery of the Precious Blood had once more outgrown its facilities. It needed to move again, and this time, far out of the more populated neighborhoods to a new monastery on Fort Hamilton Parkway, between 51st and 52nd Streets, in Borough Park. Its supporters began raising money, again drawing from all of the Catholic organizations and societies across Brooklyn, especially the ladies’ societies. It once again had fairs and bazaars, lectures, concerts, theater parties, dinners and other fundraising events.

The plans for the new building were drawn up towards the end of 1908. The architects for this project were the Manhattan firm of Reilly & Steinback. The building was made of Harvard brick, limestone and granite. The building was almost finished when it was dedicated, and the order moved in in 1910. For the rest of the run of the Brooklyn Eagle, until 1954, the monastery stayed in the news, with constant activities, fund raisers, programs, and news of additions and new facilities and programs. It remains there to this day, although I don’t think the nuns are cloistered anymore. The new monastery is twice as big as the Putnam Avenue site, as are the grounds. It’s a beautiful building in a beautiful setting.

Back on Putnam Avenue, the lots were sold and the monastery was torn down soon after the nuns left. In 1913, a judge from the Gates Avenue Courthouse issued a warrant for a truck driver who did not appear in court after being picked up for driving on the sidewalk on Jefferson Avenue. He was delivering dirt to fill in the pit left by the demolition of the building. Soon after, two sets of twin, six-story apartment buildings were built on the site. The two on Putnam still have most of their original detail. The two on Jefferson did not fare as well. But all four are still there. The cloistered monastery disappeared without a trace, or a memory. Thank goodness for maps, or we’d never know what came before.

I remember going with my mother to the cloister on Ft Hamilton Pkwy to buy mass cards. You entered a somber little room and the nuns selling the cards were in a booth behind a screen. When they opened the screen to do the sale you could vaguely see their faces through a filter (screen and/or fabric?). I don’t ever remember them speaking. The mass cards were large and colorful. When I was older my mother would send me alone to buy them on the way home from school (now closed) on Ft Hamilton Pkwy and 41st St..

I didn’t know they originated in Bed Sty. Thanks for the history.