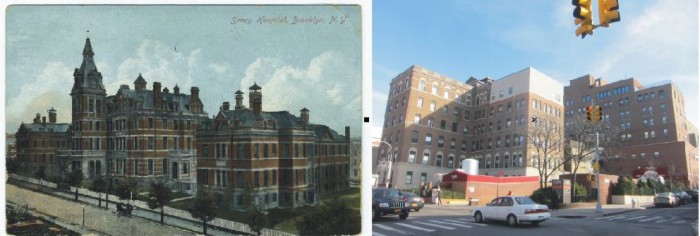

Past and Present: The Seney Hospital

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. Park Slope’s New York Methodist Hospital is much in the news nowadays due to its plans to demolish the row houses and apartment buildings it owns in order to expand its hospital and clinic facilities. But how did Methodist end up being in Park Slope in the first…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

Park Slope’s New York Methodist Hospital is much in the news nowadays due to its plans to demolish the row houses and apartment buildings it owns in order to expand its hospital and clinic facilities. But how did Methodist end up being in Park Slope in the first place? Well, there is quite a difference between today’s modern hospital and the buildings that made up the original complex. There is even a difference in the name; Methodist Hospital was built as the Seney Hospital. It was founded by a man of great philanthropy and generosity named George Ingraham Seney.

George Seney was the son of a Methodist preacher. He began his professional career as a bank teller at the Metropolitan National Bank of New York. In 1855 he was promoted to cashier, a management position, and by 1877, he was president of the bank. He was also an astute stock investor, and actually made the bulk of his considerable fortune by investing in railroads. When one of his companies, the lucrative New York-Chicago-St. Louis Railroad was sold to the Vanderbilts, he had more money than most people could imagine.

A generous and religious man, he gave large donations to his favorite charities, including his alma mater, Wesleyan University, as well as the Long Island Historical Society, the Industrial Home for Homeless Children, the Brooklyn Eye and Ear Infirmary and the Brooklyn Library. In 1881, George Seney read a story in a Methodist magazine about a man who was the organist at the author’s church. The man had come to New York City, where he was struck by a team of panicked horses. As he lay dying in the street, there was nothing anyone could do for him, as there were no local hospitals. The man died.

The author of the story, a Rev. James Buckley, was furious that his fellow Methodists were too busy building churches, and worrying about saving souls, but not doing anything about saving lives. He called for Methodists to put their faith in action and build some hospitals. The story so moved Mr. Seney that he announced to the public via the Brooklyn Eagle that he was going to buy some property in Brooklyn, donate it to the city, and fund the building of a public hospital which would open its doors to anyone, no matter their income, race, creed or color.

In August of 1881, he made good on his word, and presented the city with a large plot of land in what was called “Prospect Heights” at the time. It consisted of sixteen lots on Seventh Avenue to Eighth Avenue, from 6th to 7th Streets. He gave the deed to the city of Brooklyn, along with a check for $100,000. His only stipulations were that the hospital would be run by the Methodist Episcopal Church, with a board of managers who represented the Church; influential and charitable men such as Mr. Seney and other philanthropists, and medical professionals. He asked that it be named the Seney Hospital, after his minister father. The city had no problem with his requests.

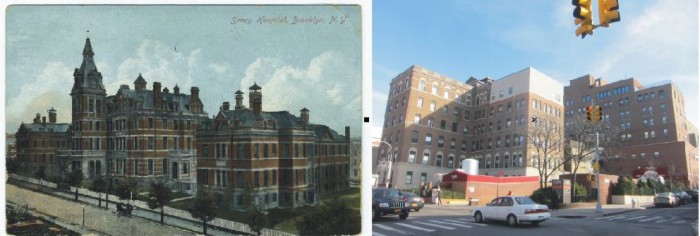

Seney Hospital was designed by a Brooklyn architect named James Mumford, Jr. We don’t know all that much about him, but he was a popular architect in the Park Slope area, and his design won the contest held to pick an architect for the project. The new hospital would be a complex of nine separate buildings, three of which would be started right away. Mumford and Seney got along well, with the elder Seney becoming a mentor and friend.

Unfortunately, as work began, so too did the Panic of 1884. George Seney, as president of his Metropolitan National Bank, was caught up in the resulting financial meltdown, and some of his loans and investments were called into question, causing the bank to almost collapse. Seney resigned his position, paid off all of the bank’s losses from his personal fortune, and had to see his famous art collection and his palatial home on Montague Terrace in Brooklyn Heights sold to pay off the debt.

His creditors took everything he had, leaving his wife and nine children without many options. He also was unable to continue to fund the hospital, which was not even open yet. Fortunately, the Methodist community rallied around the project, and raised enough money to keep the construction going, at least for a while. But the fickle press, which had declared him a saint and financial genius, was now calling him irresponsible and everything but criminal. On doctor’s orders, the Seney family took their dwindling resources and booked a long trip to Europe. Many people thought Seney would never come back. He certainly would never be able to finish his hospital. They were wrong.

The Seney’s stayed in Europe for a few months, and then came back, staying at the family’s summer home in Bernardsville, New Jersey. From there, George Seney began to get his mojo back. Using his old railroad connections, he began a new fortune, and in the course of only two years made back every cent he lost, paid off all of his personal debts, as well as the debts incurred by his bank, the insurance company he was also on the board of, and anyone else he felt he owed money to.

The construction of Seney Hospital had to be shut down for most of the two years he was gone from the scene. Architect Mumford always believed his patron would be back, but he was one of only a few who truly believed that to be true. With Mr. Seney well on his way to amassing a second fortune, the Methodist community raised enough money to finish the Western Wing of the hospital.

It opened to great fanfare in 1887; a modern, state of the art hospital that could treat hundreds in its clinic, and had beds for 70 patients. Before the hospital was finished, George Seney donated at least $400,000 to the hospital. That would be the equivalent of over $9 million today. The complex was finally completed, and began its mission to serve anyone in need.

The revitalized George Seney bought back his house at 4 Montague Street, he regained or replenished his art collection, and he was even wealthier than he was before. In 1890 he was diagnosed with serious heart disease. His course of action was to give away even more. He gave generously to the Brooklyn branch of the YMCA, to Negro education in the South, the Methodist Orphan Asylum, his Methodist Church in Bernardsville, the Seney Hospital, and always to his alma mater, Wesleyan University. George Seney died, surrounded by his family, in 1893.

Methodist Hospital continues to this day. It’s now called officially New York Methodist Hospital. It’s really too bad they didn’t keep the Seney name. A great man like that should be remembered. But the hospital he built and would recognize is gone, anyway. None of the original buildings designed by James Mumford remain. We like some buildings old and venerable. Hospitals do not fall into that category. New buildings represent new technology and new medical advances for most people, even those who love old buildings. The New York Methodist Hospital will no doubt continue to change.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment