Past and Present: The Skillman Street Gasholder House

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. There are no more gasholder buildings in Brooklyn. While we still have an example of just about every other kind of industrial building still standing somewhere within our borders, the gasholder houses are all gone. They were the most visible signs of an invisible necessity – gas, the…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

There are no more gasholder buildings in Brooklyn. While we still have an example of just about every other kind of industrial building still standing somewhere within our borders, the gasholder houses are all gone. They were the most visible signs of an invisible necessity – gas, the substance that lit the houses and streets of the city throughout much of the 19th century.

We still use gas now, but now it’s natural gas. The gas of the 19th century was coal gas, a much different substance that needed to be contained in bulk. Coal gas had to be manufactured, and simply put, was the product of baking coal at high temperatures, and capturing the gases released by the process. The gases were then further purified and stored for later use. The coal burning gas plants were close by, if not right next door to, the gasholder buildings.

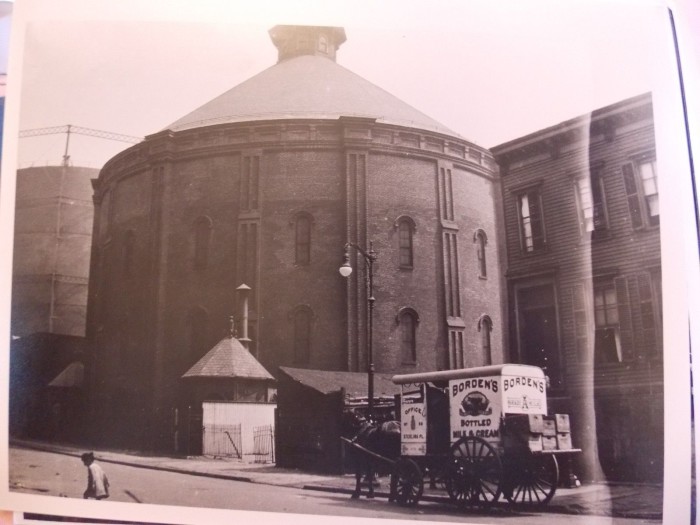

The brick buildings themselves did not hold the gas; they were built to hold the gasholder. This was a huge iron tank that took up most of the interior of the building. It had two pieces that fit together like a telescope. The size of the tank would change according to the amount of gas inside. When it was full, the tank was fully extended, as the pressure of the gas caused the inside half to rise up to its full height.

The weight of the tank kept the gas pressurized, and forced it through the pipes, and on out to customers. As the gas decreased, the tank lowered, still keeping the pressure constant. The base of the gasholder was submerged in water, which prevented gas leaks. Most of the tank, as well as the large pipes that led from and to it, were sunk into the ground. When the gasholder was empty, the top part of the tank telescoped down into the ground, and was at ground level. It was a rather sophisticated, yet simple system.

The brick gasholder house was not necessary to the actual process of storing gas. The earliest gasholder tanks stood out in the open with no building around them. But they were subject to the elements, and had to be thickly plated. Even so, the pressure of the gas was uneven as the tank reacted to sun, wind and snow pressures, and the water on the bottom of the tank often froze, causing problems in delivery.

These round brick structures were built to protect the tank from the elements. Since the tanks themselves no longer had to withstand snow or wind, they could now be built of thinner plating. The brick gashouse also calmed the fears of the public as to the safety of gas and its production. Passing this large, distinctive, and formidable looking building, on the edge of a residential neighborhood, one couldn’t help but think it was safe. It certainly looked safe. And it was a good looking building, too.

As the need for gas increased as the century went on, the gas companies began to build even larger tanks. Advances in tank construction and steel production had resulted in a new kind of gasholder. They were not clad in these wonderful brick houses, but sheathed in a much more utilitarian steel shell. You will often find photographs of gasworks that had both kinds of gasholders. The brick ones are always older.

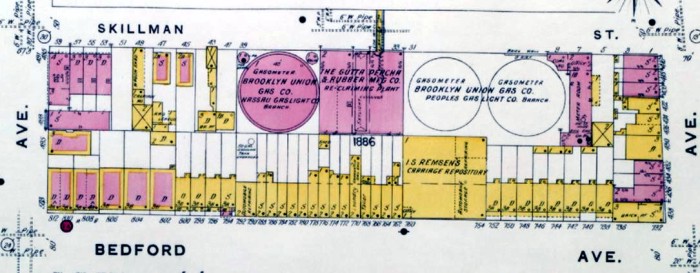

A look at the map of Skillman Street in 1904 shows the gasworks in the photograph. There were two different companies operating on this block. The brick gashouse belonged to the Nassau Gaslight Company, which was part of the Pratt family’s oil business. Down the block were two newer tanks owned by one of their rivals, the Peoples Gaslight Company. Both companies supplied the residents of Clinton Hill, Wallabout and Bedford with gas. In 1895, both companies were part of a much larger merger of many of Brooklyn’s gas companies into Brooklyn Union Gas.

The name “gasometer” on the map is an old word that was used in the early production of coal gas, and it stuck. The amount of gas in the tanks used to be measured by changes to the tank, making it a rudimentary meter. Later technological advances in metering made the name obsolete, but it had already become a part of the lexicon. Most of the gasholder houses of this type were built between 1873 and 1885.

By the 1920s, the gasholder houses began to disappear. Natural gas replaced manufactured coal gas, and the large storage tanks were no longer necessary. The coal burning plants were no longer necessary either, and most of them were torn down. They left all kinds of toxic wastes. The steel gasholders were usually sold for scrap, and the buildings demolished. Today, there are less than a dozen gasholder houses left in the United States. Most of them are in New England, and three are located in upstate New York, including one in Troy.

The photograph dates from 1923. The Skillman site was probably torn down soon afterwards. City records are notoriously inaccurate, but list the rather insipid industrial buildings that replaced them as all dating to 1926, give or take a couple of years. Today, this part of the neighborhood is no longer completely industrial, but home to the growing Satmar community of Williamsburg, which has turned the warehouse space now occupying the site into a catering hall.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment