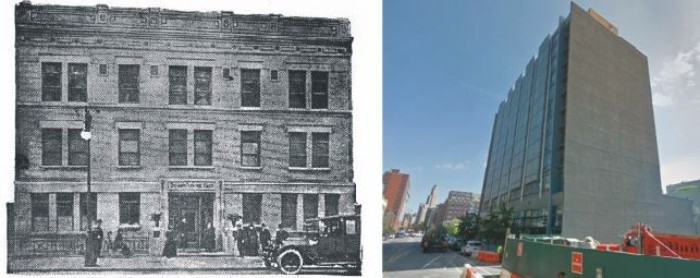

Past and Present: The Slyvan Electric Bath, Good for What Ails You

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. For as long as mankind has been around, we’ve been trying to find ways to alleviate our aches and pains. In late 19th and early 20th century America, advances in science combined with ancient cures had been shown to produce results. Mineral and hot springs baths were one…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

For as long as mankind has been around, we’ve been trying to find ways to alleviate our aches and pains. In late 19th and early 20th century America, advances in science combined with ancient cures had been shown to produce results.

Mineral and hot springs baths were one popular way to sooth aching limbs and calm agitated organs. The resort towns of Sharon Springs, Saratoga and other locations in upstate New York were popular places to get the cure. Fortunes were made by spa owners, and entire towns dedicated to hosting the guests of these spas flourished for many years.

But you had to have time to go there, and you had to be wealthy, or at least well-off. Didn’t everyone deserve to benefit from nature’s cures? And if you lived in New York City, wouldn’t it be great if there was a place in the city itself where you could take a treatment, and then walk back out onto the street and continue your busy day? Some savvy entrepreneurs thought so, and decided to bring the spa experience to Brooklyn.

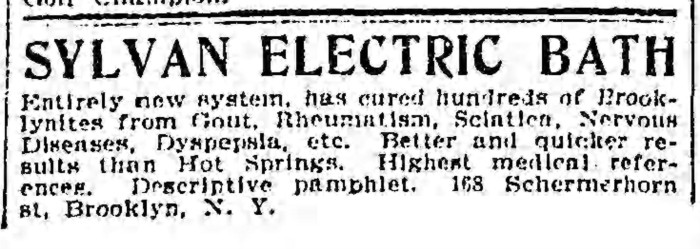

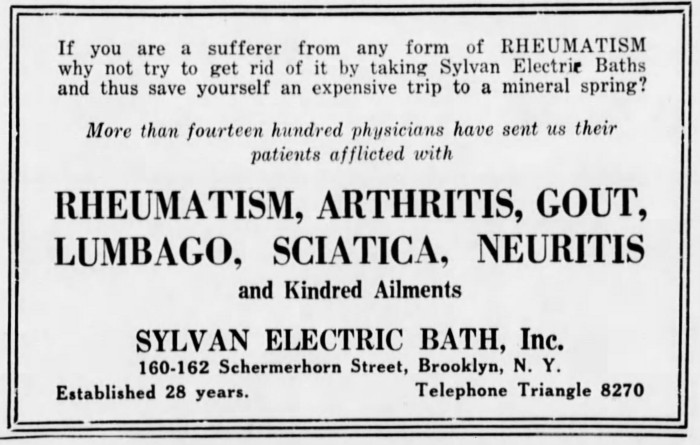

In 1900, the first ads began appearing in the Brooklyn Eagle touting the new Sylvan Electric Baths, located at 168 Schermerhorn Street, in downtown Brooklyn.

The ad said that the baths were better and quicker than hot springs, and could cure you of gout, rheumatism, sciatica and nervous diseases. They were a little vague on what was going on, but you were welcome to come by and see for yourself and get a descriptive brochure.

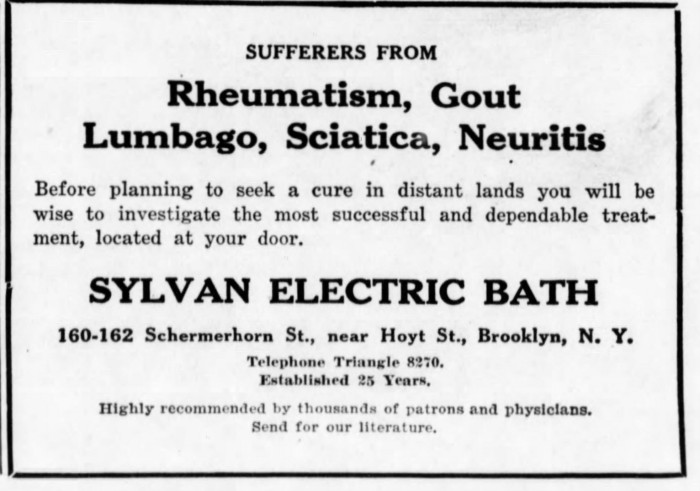

Most people knew that hot springs and mineral baths could be very therapeutic, and having such a facility only a walk or trolley ride away was worth investigating. The Sylvan Baths started to thrive.

Later ads began to explain how the cure worked. The baths were heated and stimulated by electric current. Immersing yourself in them opened up the pores, and flushed out the toxins. The current stimulated the organs back to health. Basically, it was a hot tub.

Like the hot tub craze of the late 20th century, soon everyone wanted to experience the electric waters. In 1904, the State of New York granted a certificate of incorporation to the Sylvan Electric Bath Company of Brooklyn. They proposed to install their unique bath facilities in hospitals, infirmaries and health resorts.

The corporation had half a million dollars’ worth of capital stock. The directors of the company were James H. Lancaster, Z. Taylor Jones and Frank Barritt, all of Brooklyn.

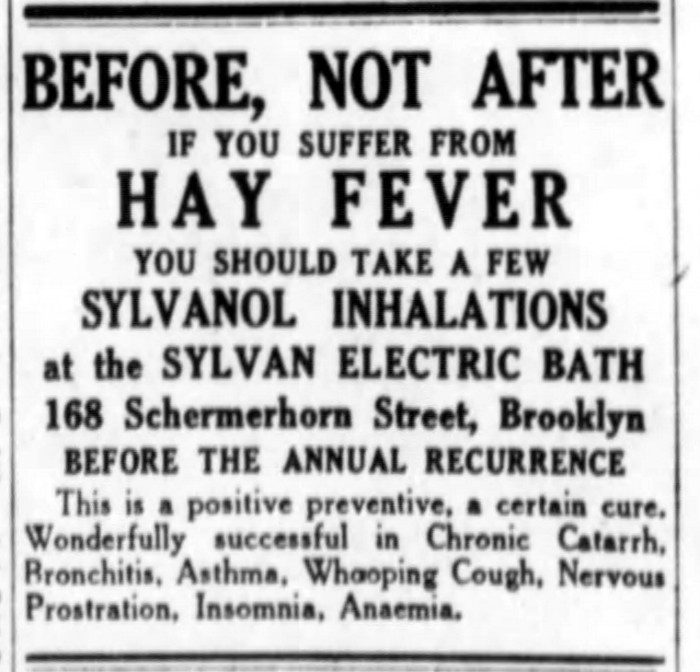

The Baths operated at 168 Schermerhorn for 14 years, during which time they added to the basic bath treatment. They started to offer “Sylvanol Inhalations” to alleviate the sufferings of those with allergies, hay fever, asthma and insomnia.

That treatment could have been nothing more than a steamy inhalation of eucalyptus or menthol, or some other combination of herbs. But to people who suffered from these conditions, it was heaven sent.

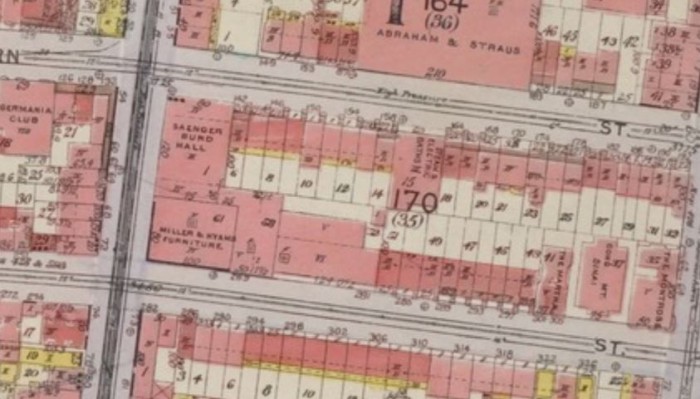

In 1915, the Baths decided to expand. The facilities at 168 were now far too small. They purchased land next door and commissioned architect William P. Tuthill of Manhattan to design a three story bath complex. The new address was 160-162 Schermerhorn Street.

The building was 60×95 feet, and was located in the middle of the block of Schermerhorn, between Hoyt and Smith Streets. The building cost $40,000 to build, and opened in 1916.

The Slyvan Baths were open to both men and women, but they really catered to middle and upper-middle class women, most of whom did not work during the day. The baths were segregated by sex, of course, and probably segregated by race as well, as were most facilities of the day.

The baths’ core clientele was women who suffered from what were popularly called “nervous diseases.” These included hysteria, fainting spells and headaches, depression, hypochondria, and various other neuroses. Popular thought was that women’s delicate natures combined with city living brought these diseases on. Regular sessions at the baths could cure it, or so said their advertising. It didn’t always work.

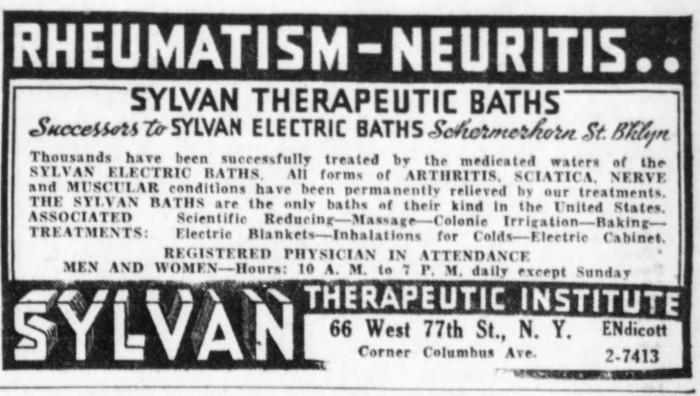

By the 1920s, the Baths were offering all kinds of treatments. You could get the spa baths as always, but you could also be treated for various ailments by being baked, massaged, or wrapped in electric blankets. You could also have a colonic cleanse.

On October 10, 1923, Mrs. Alfred Blye of Sheepshead Bay was found in the backyard of the Baths, dead. She had been suffering from acute stomach problems and had come to the Baths for several months for treatments. Mrs. Blye had been in a room on the second floor, and had gone to the roof from there, still clad in her treatment kimono.

Investigators found that she had slit her wrist before jumping or falling off the roof to her death. She had recently complained that the pain was too much to bear. One wonders if she had gone to the hospital. She could have had an ulcer, cancer, or some other disease that baths would not have cured.

While the baths proved popular well into the 1920s, the opportunities for problems kept their lawyers busy. In 1924, the Baths were sued by Henry Appel of Ridgewood. He had gone there for treatment of rheumatism. They had placed him on the equivalent of a tanning bed and subjected his legs to a heat treatment.

Unfortunately, they had then left him alone too long, and he was burned. The Baths’ lawyers alleged that the treatment was also used in government facilities, and exposure to the heat was not dangerous. His burned legs said otherwise, and he was awarded $2,000.

In 1933, Slyvan Baths closed up shop in Brooklyn. They relocated in Manhattan at 66 West 77th Street, on Columbus Avenue on the Upper West Side. They renamed themselves the “Sylvan Therapeutic Institute, successors to the Sylvan Electric Baths of Schermerhorn Street, Brooklyn.” The Brooklyn ads stop running that same year.

The building is long gone. That stretch of Schermerhorn has had government buildings, parking lots and empty holes in it for a long time. Today, as construction goes up all around it, 160 Schermerhorn Street is a large apartment building begun in 2007, and finished a few years later. Soothing spa baths on Schermerhorn might still be a good idea.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment