Queenswalk: The Unisphere in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park

New York City has many iconic structures that define it to the world. Some, like the Brooklyn Bridge, the Chrysler and the Empire State Buildings, are state of the art examples of architectural and engineering genius. They are all great in their own right, and are all symbolic in their own ways, so it’s not…

New York City has many iconic structures that define it to the world. Some, like the Brooklyn Bridge, the Chrysler and the Empire State Buildings, are state of the art examples of architectural and engineering genius. They are all great in their own right, and are all symbolic in their own ways, so it’s not surprising that the Unisphere joins this pantheon as a symbol of New York City and American ingenuity, as that was its intended purpose, after all.

World’s Fairs have been with us since the mid-19th century. They were organized basically, to show off each nation’s products, and to highlight the great inventions and emerging technological advances being developed. One of the best of them, the 1893 Columbian World’s Exhibition, in Chicago, introduced the world to the great technological advances of electricity and other modern marvels, and heralded in new innovations in architecture and popular culture. As the 20th century progressed, the focus moved away from just showcasing technology and products to the idea that these fairs could bring the nations of the world together and create a better society.

The 1939 World’s Fair, which was held here in Flushing Meadows- Corona Park, had the optimistic theme of “Building the World of Tomorrow,” an ambitious goal for a world still in the grip of a lingering economic depression, and on the verge of a massive world war. Twenty-five years later, in the same location, an ambitious World’s Fair would organize under the theme of “Peace Through Understanding,” striving to build an international consensus of good will in a far different world. The Unisphere was a powerful symbol of that good will.

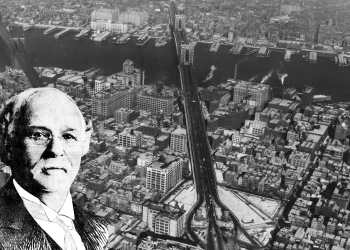

You can’t have a huge event in a New York City park, in the middle of the 20th century without the name of Robert Moses coming up, and he had a large role in both the 1939 and 1964 Fairs. By the 1920s, Flushing Meadows was quite literally a dump. Once a marsh with a creek running through it, it had been filled in during the first decades of the 20th century, with the idea of building a huge industrial park on it. World War I quashed those plans, and the area became a dumping ground.

When Robert Moses became Parks Commissioner in 1934, under Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, he was eager to fulfill a long standing dream of creating a park in Flushing Meadows. It would be part of a grand greensward that would one day stretch the length of Queens, into Nassau County. But the nation was in the middle of the Great Depression, and that dream was going to have to wait. When New York City was chosen as the city for the 1939 World’s Fair, Moses immediately suggested using what was called the “Corona Dump” as the site.

It was a win-win situation. The land would be purchased by the city and leased to the World’s Fair Committee. It would be developed for the fair, and when that was over, a year later, the temporary buildings could be torn down, and the park would remain. Plus, the city would make money from the millions attending the fair, and the rental income would pay for the new park. The city fathers agreed, and the Corona Dump was purchased. The land needed to be graded and improved, and still needed a drainage system, as it was still a swamp underneath all that landfill. Moses chose prominent landscape architect Gilmore D. Clarke to design the new site. It was an ambitious project.

The land had to be graded, trees planted, and an infrastructure of plumbing and power lines installed. Most importantly, a complex drainage system had to be laid, feeding water from Flushing Creek into two large lakes in the park. Gilmore Clarke was the man for the job. He was a New York City man, born in 1892 and educated at Cornell University. He was an Army engineer during World War I, and during the 1920s, served on several city, state and national boards as a landscape architect.

His association with Robert Moses dated from Moses’ position as the head of the NY State Commission of Parks, in the 1920s. Clarke was the landscape architect responsible for the design of a huge new Westchester County project, which included the Rye Beach Playland, the Bronx River Parkway and the Saw Mill River Parkway. In 1931 the Architectural League of New York awarded him the Gold Medal of Honor in Landscape Architecture for this project. He was now the most famous landscape architect for public works in America.

In 1934, Moses hired him as the Consulting Landscape Architect to the New York City Parks Department. In this position his projects included landscape design for the Henry Hudson Parkway, the Central Park Zoo, Orchard Beach in the Bronx and Astoria Park. He also supervised renovations to City Hall Park and Bryant Park. If that wasn’t enough, a year later he became a member of the Board of Design for the 1939 World’s Fair.

Clarke planned a Beaux-Arts design for the 1939 Fair, which featured major and minor boulevards radiating from a central point. At the ends of these boulevards, the attractions, pavilions, temporary buildings, fountains and sculpture gardens would be built. The central point contained the fair’s Trylon and Perisphere, the modernistic symbols of the fair. The Trylon was a tall pyramid shaped tower, reached by the world’s longest escalator, joined to an enormous sphere called the Perisphere, which contained a huge diorama called “Democracity.” Both buildings were designed to be temporary, and were torn down when the fair was over. The Unisphere was built in the same location as the Perisphere, twenty-five years later.

The 1939 World’s Fair was not a financial success, and the World’s Fair Corporation ended up filing for bankruptcy in 1940. Moses was not able to get the grand park he wanted after the fair buildings were torn down, but there was enough work done to open Flushing Meadows Park, in 1941. A generation later, when New York City was awarded the 1964 World’s Fair, Moses, who was still around, and in office, offered Flushing Meadows Park as the ideal site, and it was once again chosen for the Fair.

Robert Moses, who was at the end of his career, and also at the lowest point of his popularity, was chosen as the President of the Fair Corporation. Gilmore Clarke was still around too, and once again, he was picked as the landscape architect for the project. His job was to take the footprint of the 1939 fair and adapt it to the new fair. The theme for the 1964 fair was “Peace through understanding in a shrinking globe and in an expanding universe.” It was an ambitious theme for a world where the superpowers were engaged in a frightening Cold War with nuclear proliferation, and assured mutual destruction. It was also an exciting world with the dawn of space exploration, and a modern world of steel and glass towers, technological advances, and the hope of a brave new world.

Clarke designed the Unisphere as an armillary sphere; a stainless steel globe ringed with three orbital rings representing the flight paths of the Russian cosmonaut Uri Gagarin, the first man in space; John Glenn, the first American to orbit the earth; and Telstar, the first communications satellite. The steel was donated by the United States Steel Corporation, and was constructed by the American Bridge Company. It was placed in the same location as the 1939 Perisphere, and is built on the structural foundation that supported it, as well. The sphere is estimated to weigh 900,000 pounds, which includes the weight of the 100 ton tripod base. It rises 140 feet, and the diameter in 120 feet. It’s the largest global structure in the world.

The globe is an engineering marvel. The steel cage that supports the continents represents lines of latitude and longitude, as well as being the structural elements to hold the thing together. Great care was taken in the choice of steel. Stainless steel was chosen to resist corrosion from the seasons and the elements, including salt water and pollution. Different grades of stainless were chosen too, for reflective and display purposes. To show elevations and topography in the land masses, the steel was built up in plates and contoured. The distribution of weight had to be calculated, as the land masses are not equal in all parts of the globe, and it all had to balance, while retaining geographic integrity. Clarke and his team outdid themselves.

The Unisphere originally had reflective lights that pinpointed the capital cities of the world. In honor of the work of the Mohawk ironworkers who built the sphere, a light was placed at the site of the Kahnawake Indian Reservation, located on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River, in Quebec. The Unisphere is surrounded by a large circular pool and a double ring of fountains. When operating, the jets of the fountains were designed to mask the base of the sphere, making it appear to be floating above the ground. Dramatic lighting at night also reinforced the sphere’s other-worldly quality.

As hoped, the Unisphere was the symbol of the 1964 World’s Fair. Its likeness was used in souvenirs, advertising, and anywhere else it could be utilized. The World’s Fair Corporation got a commission on all of it. The image and the word “Unisphere” were trademarked and copywrited by the Corporation, as well. In spite of everything, the 1964 World’s Fair was also not a financial success, and attendance was well below expectations. At the end of it all, there was enough money in the coffers to bulldoze the bankrupt exhibitor’s buildings, and restore the park back to the basic Beaux-Arts design that Clarke envisioned. Fortunately, they kept the Unisphere, and in the years since, it has become a symbol of Queens.

However, you can’t just leave it sitting there, unmaintained, and expect it to last forever. By the 1970s, when the city was broke and the Parks Department was basically unfunded, the Unisphere suffered. The fountains were broken and shut down, the empty pool was scarred with graffiti, and the sphere was covered in grime. In 1989, the 50th and 25th anniversaries of the two World’s Fairs, a massive multi-million dollar rehab project of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park was undertaken. The entire park was refurbished and restored, and a great deal of work was done on the Unisphere and the pool and fountains.

The fountains were repaired, with new pumps and timers, and the pool repaired and resurfaced. The globe got some well-needed structural repair, with many of the steel reinforcements replaced and strengthened, the cables replaced, and the globe cleaned with a special solution and an inside and out power washing. The new park was re-opened, with the lights shining and the fountains once again jetting upwards on May 31, 1994. The work was all funded by the Queens Borough President’s office.

In 1995, the Landmarks Preservation Commission bestowed landmarking on the Unisphere, insuring its survival, and noting its importance to the City of New York. In 2010, the New York State Pavilion received landmark status as well. Both of those designations came in handy when the Men in Black had to stop a giant alien bug from destroying the planet in 1996. That iconic movie scene only helped solidify the importance of this great monument to world unity and peace, and has become part of the Unisphere’s story. GMAP

(Photo:Ourenglish.com)

What’s in the works for Flushing Meadows park today? It feels like the park could become more of a focal point for the borough as Prospect Park is for Brooklyn and Central Park is for Manhattan. You can’t say the park is underutilized, but it doesn’t inspire civic pride, nor is it a destination. Queens residents, what can we do to make this park a bigger part of our lives?

Great article as always!

I always try to remember (and it does boggle the mind somewhat…) that the Corona Dumps – the site of the park and other edifices like the stadiums – was the “Valley of Ashes” that Fitzgerald described in The Great Gatsby – approximately where Northern Blvd, the way into town from West Egg, met the train tracks and the ash scows in the bay. Quite the change….

The Unisphere has always been my favorite NYC icon (aside from Lou Reed and the Ramones). I moved here pre-“Men In Black” and couldn’t believe there was this cool, enormous, quite neglected-looking thing just plunked in the middle of Queens. At the time, its existence was basically unknown outside the NY area, unlike landmarks such as the Empire State Bldg, etc.

I agree. The UNISPHERE is one of the coolest things in NYC…

The Unisphere is a thing of beauty. I thought so when I first saw it at the World’s Fair when I was nine and I still think so today.

Keep up the great work Brownstoner!