Past and Present: How a Red Hook Company Pioneered Steel-Frame Construction

This month marks Brownstoner’s Steel Anniversary. We’re taking some time to look back at our past, even as we design a new future. A look at Brooklyn, then and now. Modern steel-frame construction dates back to the 1880s. The idea of using iron or steel to support a building had been around for a while,…

This month marks Brownstoner’s Steel Anniversary. We’re taking some time to look back at our past, even as we design a new future.

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

Modern steel-frame construction dates back to the 1880s. The idea of using iron or steel to support a building had been around for a while, but prior to 1885 it was only used for small elements, such as in the framework of an oriel or bay, and only used in structures of only a few stories.

The first tall building to use structural steel in its frame was the 10-story Home Insurance Company Building in Chicago, built in 1885. Even then, it had only a partial steel skeleton, the back of the building was totally brick, it had granite piers and was clad in cast iron, which helped support it.

Still, it was a momentous start that led to the first true completely steel-framed “skyscraper,” also a Chicago building. That one, the Rand McNally Building, was also 10 stories tall, but much larger, taking up two-thirds of a city block.

Auspiciously, it was designed by Daniel Hudson Burnham, who was the official architect of the 1893 World’s Chicago Exhibition and the architect of Manhattan’s iconic skyscraper the Flatiron Building. Steel-frame construction was about to take over the world.

The Rand McNally building was finished in 1890, and in addition to the publishing company, it also housed Burnham’s offices for the World’s Exhibition. Since this was the first major steel-frame building, you’d think it would be a Chicago landmark. It never got the chance, it was torn down for a taller (also steel-framed) building only 20 years later.

What is Steel-Frame Construction?

Steel-frame construction is a given in most large buildings today — we are used to the metal skeletons rising in our urban landscape.

But structural steel, like most innovations, had to be proven to work before it was allowed to be used. Engineers and architects who made up Departments of Buildings across the country wanted to make sure this new technology was sound.

Vertical steel columns and horizontal I-beams make up the complex grid that form a building’s skeleton. The columns are of thicker and wider steel than the I-beams, which have flanges on both ends, all of which distribute the compressive stress on the entire structure.

From there, different methods of construction can be used, including round or square tubes of steel that are filled with concrete. Often sheets of steel are used to create surfaces upon which concrete floors are poured, also with additional steel rebar.

Building materials such as concrete, stone or brick can clad the building, with all kinds of other materials used inside. Steel construction also allows for the material to be used in the interior, as in the case of galvanized steel studs used in building partition walls.

The structural steel is connected to itself by the use of bolts and rivets, as well as welds. Here’s where our story travels to Brooklyn, home to the first welded steel-framed building in New York City.

A History of Electric Welding

Welding is simply connecting two pieces of material using a fusion process, generally heat. Here’s a brief history.

1800: Alessandro Volta discovered that two dissimilar metals connected by a substance become a conductor when moistened, creating what is now called a “voltaic cell.”

1820: Andre-Marie Ampere pioneered in the field of electromagnetism.

1836: Sir Edmund Davy discovered acetylene and developed the first acetylene torch.

1831: Alexander Faraday invented the Dynamo and created electricity from magnets.

1838: Charles Goodyear patented his rubber vulcanization process, enabling later manufacture of hoses for welding equipment.

1856: James Joule experimented with wires in charcoal, welding them by heating with electric current. This was the first internal resistance weld.

1887: Nikolai Benardos and Stanislav Olszewaski got an American patent for the apparatus used in their carbon arc welding process.

1888: Benardos and Olszewaski got a U.S. patent for carbon arc welding.

1890: C. Coffin in Detroit issued a patent for carbon metal electrodes for his patented process called electric arc welding. Two years later, he introduced the bare metallic electrode.

Other discoveries, improvements and innovations by a host of people across America and Europe soon resulted in the welding techniques we are familiar with today, especially acetylene and arc welding, also called electric welding.

The use of this technology in shipbuilding and repair, plumbing and heavy industry is obvious, and was eagerly embraced by these industries. But using welds to support a building? Would that be safe?

This was a harder sell — to the authorities, the building industry and the general public. Someone would have to go first, and a company in Brooklyn did just that.

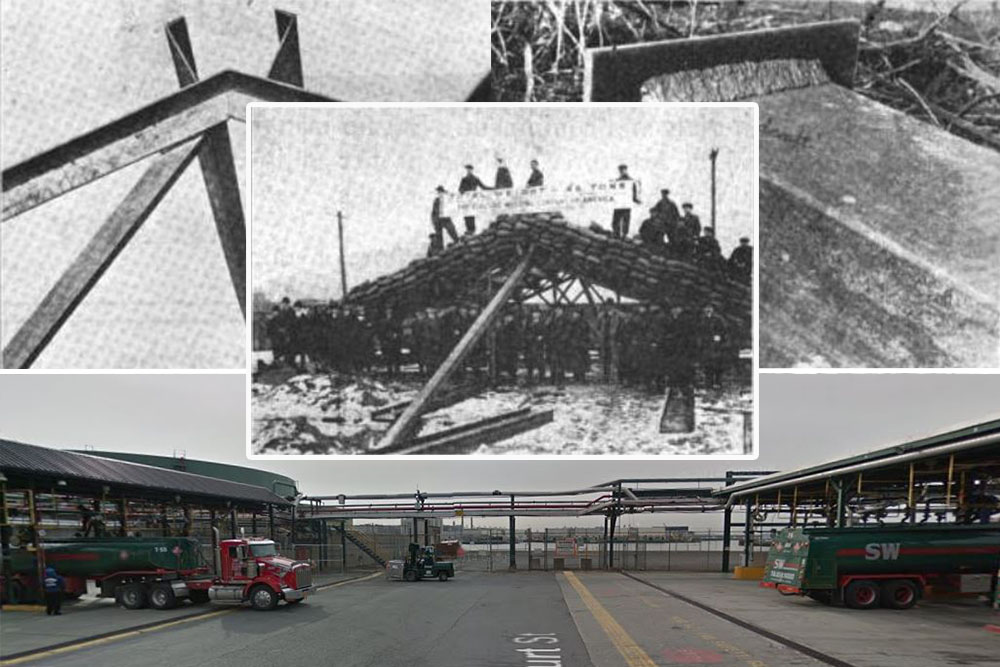

Photos via Welding Engineer magazine and Google Maps

The Electric Welding Company of Brooklyn

The Electric Welding Company of Brooklyn was established in 1908. Its initial work was in ship repair. It was located at the base of Court Street in Red Hook, at the water’s edge.

Early in 1920, it merged with at least 10 other electrical welding companies to form an umbrella company called the Associated Welding Company. The headquarters was at this location in Brooklyn.

Later in 1920, the Electric Welding Company became the first to build an electrically welded steel framed structure in the United States. The steel superstructure of the building had no rivets, only welds to hold it together. The building was built by the workmen of the Electric Welding Company and was used as their headquarters.

Before the Department of Buildings would sign off on the structure, EWC had to submit welds that had to stand up to stress tests.

The company decided to make an event out of it and get a lot of free publicity (and later business, no doubt). Workers set up some of their tests at the Crescent Athletic Club for everyone to see.

They welded the trusses for the roof put them up and ran tests. The welds not only held, but they were able to sustain more pressure than the rivets. The welds withstood 95 pounds per square foot. Riveted trusses tested at only 45 pounds per square foot.

Another weld, which joined two bars with an overlapping lap weld, was tested with direct pressure. It finally snapped, but snapped above the weld.

A set of welded roof trusses was set up, and 48 tons of pressure was piled on the trusses, using bags filled with gravel, which were piled up on wooden planking. A photograph shows the company workers standing on top of the bags.

Various kinds of welds were tested in every way possible and all passed with flying colors.

The engineers from the Electric Welding Company touted their welded steel construction with the following facts:

- Welding was much quieter than riveting in both commercial and residential neighborhoods. Welding could go on 24/7 if necessary, without disturbing people. Riveting is extremely loud.

- The need to fabricate special parts is more or less eliminated. Welds could be used to make special shapes as necessary, saving time and money.

- Welds are stronger than rivets, 100 percent compared to 60 percent.

- The structure weighs less using welds.

- A welded superstructure takes less time to build, uses less materials and is therefore cheaper all around.

The Electric Welding Company was able to build its building. The business remained nautical, mostly repairing ships. They did not go into building construction.

However, they proved that arc welding was the wave of the future, useful in all kinds of applications, including building. Further innovations in arc and other kinds of welding by many others across the country and in Europe made welded steel a viable material. Steel construction today uses both welded and riveted steel.

The Electric Welding Company building is long gone. Its address was 764 Court Street. Today, the site is part of the Coast Guard’s off-limits zone in that part of Red Hook. Court Street ends at their gate.

[Top photo: Wikipedia]

Related Stories

Walkabout: How Reinforced Concrete and the Turner Construction Company Changed the World

Walkabout: Samuel Yellin, Master of Iron

Building of the Day: Boardwalk at 16th Street

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment