How Master Builder Robert Moses Transformed Brooklyn as We Know It

More than anyone else in recent history, Robert Moses shaped the physical infrastructure of Brooklyn. We drive on his roads, stroll through his parks, live in his housing developments and are surrounded by his influence at every turn. From the 1920s through the late ’60s, Moses molded New York City like clay, creating a legacy of…

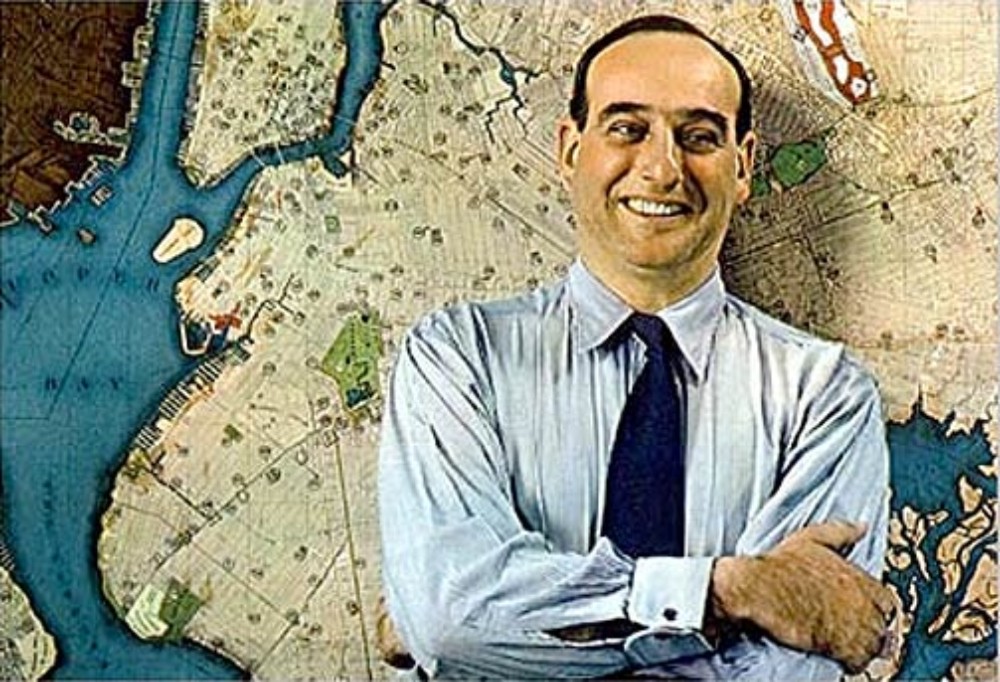

Robert Moses with model of his Brooklyn Battery Bridge. Photo via Library of Congress

More than anyone else in recent history, Robert Moses shaped the physical infrastructure of Brooklyn. We drive on his roads, stroll through his parks, live in his housing developments and are surrounded by his influence at every turn. From the 1920s through the late ’60s, Moses molded New York City like clay, creating a legacy of projects that are greatly used, while being loved, hated and controversial, even today.

Robert Moses was born in New Haven, Conn., in 1888 to wealthy German Jewish parents. When he was 11, the family moved to a townhouse on East 46th Street in Manhattan. Young Robert went back to New Haven to attend Yale, then studied at Oxford and returned to New York for his Ph.D. at Columbia.

After finishing school, he began working for the City. His head-butting with Tammany Hall brought him to the attention of Governor Al Smith, who made him Secretary of State of New York. Moses established and led various public authorities and parks and highway departments for the state — his first big impact on New York.

One of his first projects was Jones Beach, followed by the Northern, Southern, Wantagh and Meadowbrook parkways. The Taconic Parkway, Interstate 87 and others followed.

The public authorities he led were not subject to the same rules of legislation and spending as other agencies. He could draft plans, collect tolls, issue bonds, borrow money — all without the approval of elected officials or the public.

Robert Moses became the most powerful man in the state of New York.

In 1933, newly elected mayor Fiorello LaGuardia asked Moses to join his administration as head of a unified City Parks Department, and lead the new Triborough Bridge Authority. As he acquired new titles and responsibilities, he never gave up the old ones, although he was forced out of his Secretary of State job by FDR’s governorship in 1928.

In the ’30s, the Great Depression was in full swing, and lots of federal monies were available for public works projects. Moses repaired the city’s parks and established new ones. Inspired by his love of swimming, he built 11 massive public swimming pools scattered in poor neighborhoods across the city — including the one in McCarren Park.

He built bridges, housing projects and highways. He worked tirelessly, but with great power and a hand of iron. There’s not a piece of the city that escaped his influence. A catalogue of his individual accomplishments would take volumes.

Moses had an undeniable impact on Brooklyn.

Most people are aware that Robert Moses built the BQE, and chose to cut a trench through the working-class neighborhoods of what was then known as South Brooklyn, separating Red Hook from the rest of the borough and what later became Carroll Gardens.

He would have continued that trench straight through Hicks Street in Brooklyn Heights, destroying that neighborhood as well. But the people in the Heights had more political power than those in Red Hook, and the great compromise that created the Promenade saved the area — at least until Moses wanted to tear more of the neighborhood down for new apartment buildings. The result of that compromise is the high- and low-rise housing on Cadman Plaza and Henry Street. But those are not the only Moses touches in Brooklyn.

Here’s a partial listing:

- Belt Parkway

- Brooklyn Battery Tunnel

- Brooklyn-Queens Expressway/Gowanus Expressway

- Brooklyn Heights Promenade and nearby playgrounds

- Prospect Expressway

- Cadman Plaza

- Verrazano-Narrows Bridge

- McCarren Recreation Center and Pool

- Betsy Head Recreation Center and Pool

- Sunset Park Recreation Center and Pool

- Red Hook Recreation Center and Pool

- Prospect Park Zoo, Bandshell, Wollman Rink, comfort stations and children’s playgrounds — but also the destruction of many important Olmsted & Vaux structures and vistas

- Fort Greene Park: improvements, playgrounds

- Owl’s Head Park in Bay Ridge: improvements, playgrounds

- Coney Island Aquarium

- Public Housing towers: Albany Houses, Walt Whitman Houses, Gowanus Houses, Williamsburg Houses, Red Hook Houses, towers in Coney Island, Brownsville and elsewhere

The “Power Broker” eventually lost his power.

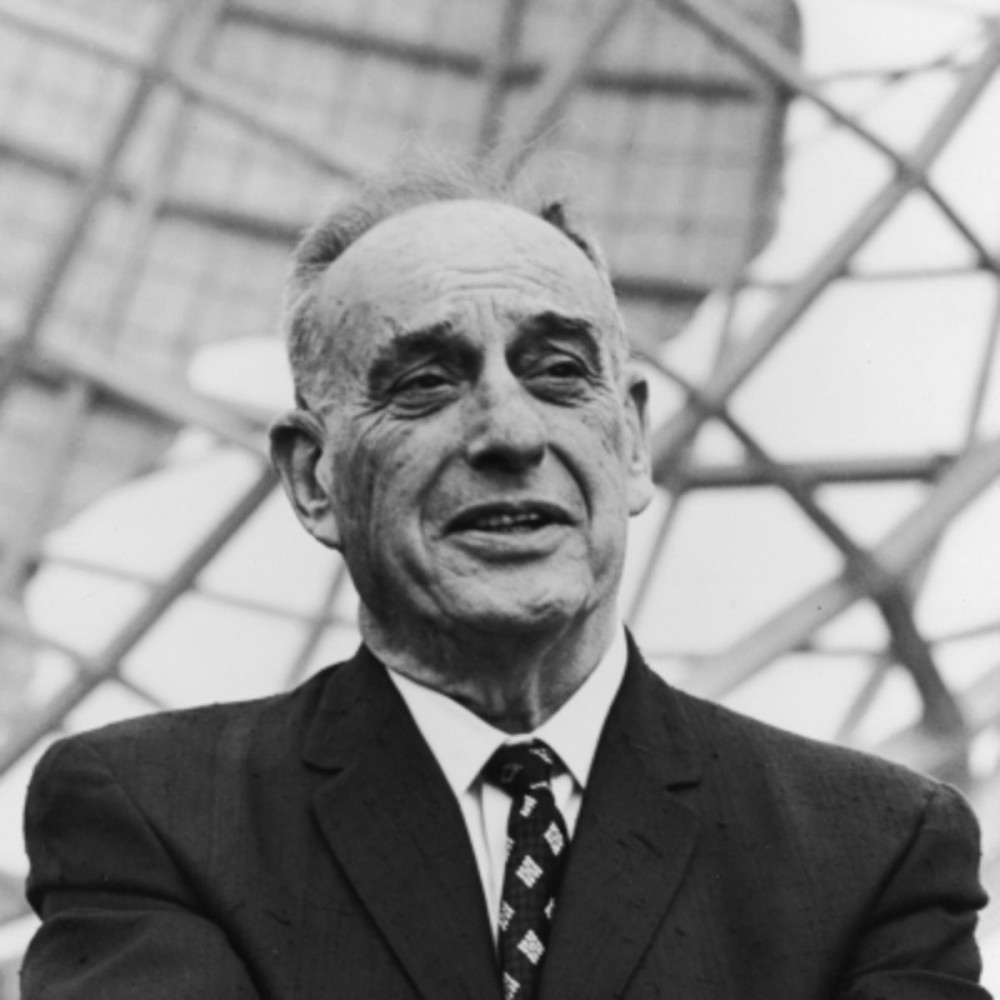

Robert Moses’s influence and reputation waned in the 1960s. His destruction of neighborhoods for highways and housing projects started to alarm people. The idea of historic preservation was taking hold across the city. Neighborhoods began to fight back.

His plan to run a highway through the center of Greenwich Village was met by Jane Jacobs and a host of activists, and was defeated. He started to lose more than he won. His last big project, the 1964 World’s Fair, was not a financial success.

In 1968, the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, which Moses had headed since the ’30s, was folded into the MTA. The new chairman, as well as the governor, Nelson Rockefeller, froze him out. Robert Moses’s power was gone.

His public works and philosophies were a mass of contradictions. He looked down on poor and working-class communities and thought nothing of plowing them under for highways. Yet he built parks and pools in many of those same neighborhoods. He truly believed cars and highways were the future, and their needs superseded the general populace; he spurned most efforts to build up mass transit.

Although Moses loved parks, he wasn’t impressed by the park builders, specifically Olmsted & Vaux. He tore down beloved and important buildings within all of their parks, generally replacing them with banal and utilitarian concrete buildings and facilities. Today, Prospect Park has begun efforts to reverse some of those changes, including the new Lakeside center.

Like many of his contemporaries, Robert Moses operated with a casual racism: “That Moses was highhanded, racist and contemptuous of the poor draws no argument even from the most ardent revisionists,” the New York Times’ Michael Powell wrote in a 2007 story about Robert Caro, author of the iconic Moses biography The Power Broker.

Moses’s housing projects replaced 19th-century neighborhoods, not because of a great regard for the lives of the people in them, but as part of his desire to reshape the environment of the city, and make it look more orderly and modern.

Robert Moses retired to Long Island, and died in 1981 of heart disease, at the age of 92. He’s buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. Thirty-five years after his death, he is still one of the most talked-about figures in New York history.

Related Stories

What Is ULURP? And Why Do We Have It?

Past and Present: Decades of Change for Fort Greene’s Cumberland Street Hospital

The Making of Brooklyn’s Cadman Plaza

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook. [sc:mailchimp-books ]

I was in the Bronx last week. He sure chopped that up with highways. It’s like a series of islands with no crossings except by vehicle.

Moses did not assume control of the construction of public housing until after LaGuardia left City Hall. Accordingly to Caro, the Little Flower just did not trust giving him that responsibility. Thus he was NOT responsible for the construction of such terrific developments as Williamsburg Housing. Once he assumed control of public housing in the late 1940’s, those NYCHA developments that we all love to hate came to fruition.

hey benson. whats up?

It is not. Thanks!