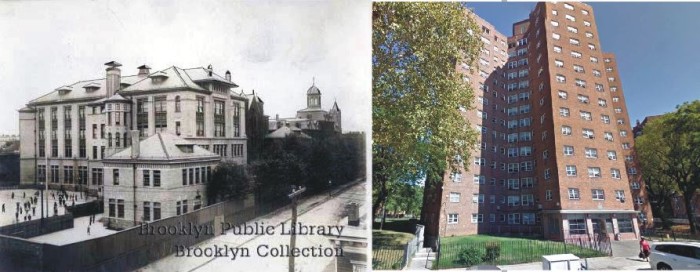

Past and Present: The St. John’s Home for Boys Becomes the Albany Houses

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. In the latter part of the 19th century, the eastern part of Central Brooklyn radiating north and south of Atlantic Avenue became the go-to neighborhood for large charitable institutions. Encompassing parts of the present-day neighborhoods of Bedford Stuyvesant and Crown Heights, this area once teemed with hospitals, old…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

In the latter part of the 19th century, the eastern part of Central Brooklyn radiating north and south of Atlantic Avenue became the go-to neighborhood for large charitable institutions.

Encompassing parts of the present-day neighborhoods of Bedford Stuyvesant and Crown Heights, this area once teemed with hospitals, old age homes, orphanages and sanitariums. There were multiples of all of these facilities, as all were segregated by race, religion and gender. Land was cheap.

The St. John’s Home for Boys was founded in 1868, a part of the Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum Society. It was a time when more and more poor Catholic immigrants (especially Irish) were pouring into Brooklyn, and the need for charitable facilities was on the rise.

St. John’s Home for Boys was located on the block of St. Marks Avenue running to Prospect Place, between Albany and Troy Avenues. Back then, the neighborhood was in Bedford, but today we’d call it Crown Heights North.

1904 Sanborn map, New York Public Library

At its largest, St. John’s was a huge block-long facility, a complex that had a central building, second dormitory, a large chapel, hospital, kitchen and laundry facilities, and a power plant. It also included a large athletic field next door in the block between Prospect and Park Places. The 1904 map gives a great look at the size of the facility.

The home was run by the Sisters of St. Joseph. During the 19th century, all of the boys were of Irish descent, and were joined by Italians and others as the institution continued in the 20th century.

Brooklyn Public Library

The boys were not all orphans; some were placed in the home by the courts because their parents couldn’t care for them, or were in prison or in some kind of care themselves. Many destitute mothers handed their boys over to the home, and came to visit as they were able.

On a cold night in December, 1884, the main wing of the building was engulfed in one of Brooklyn’s worst fire disasters. At least 21 children and five adults died in the blaze, some of whom were never fully identified. The story of that fire was told in a Walkabout piece entitled “The Lost Boys of St. John’s.”

The Home received all kinds of donations after the fire, and was able to immediately rebuild. They expanded their facilities, adding a new dormitory at the end of the 19th century. At the institution’s peak, they were providing shelter and education to over a thousand boys.

All the while, the neighborhood grew up around them. A block from the Home, one of the richest neighborhoods in Brooklyn developed, taking the name of the street – the St. Marks District.

1929 photo: New York Public Library

By the beginning of the 20th century, the blocks surrounding St. John’s and its athletic field were the site of two-family row houses and small apartment buildings. They enclosed the institution and spread eastward towards Weeksville, and on to East New York and Brownsville.

By the Great Depression, St. Marks Avenue between Kingston and Albany was now called Doctor’s Row, as the old mansions became home offices for all kinds of medical practices. The rest of the St. Marks district was redeveloped from mansion blocks to large elevator apartment building blocks. The area was still solidly middle class, and had a large Jewish, German and Irish population.

At that time, African Americans were moving into Bedford Stuyvesant in greater numbers, including here. Lower income folk of all nationalities were settling in east of St. John’s Home. Because of the Depression, everyone was doing badly, and the Home was no exception. Donations declined as more children needed help.

Brooklyn Public Library

Then World War II erupted.

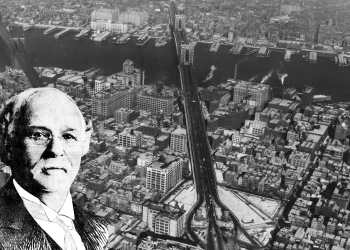

Before the war, the City of New York had embarked on a new housing program, resulting in the creation of the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) in 1934. Under the local auspices of City Planner Robert Moses, new low-income housing projects had been built in several locations around the city, including in Brooklyn: the Williamsburg Houses and the Red Hook Houses.

These were not just single buildings, but entire complexes, some large enough to include new public schools. Many were built on the principles espoused by European planners and architects such as Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier, who were doing their own social building projects in Europe.

The early housing projects were pretty low-rise, mostly 4-6 stories. But as costs for building and land increased, and the need for more units soared, the idea of the housing tower came into vogue. Walter Gropius himself had extolled the idea of housing towers surrounded by parkland.

After World War II ended, New York City needed more housing, big time. Returning soldiers, displaced workers, a lot of new immigrants, and a migration of poor blacks tired of Jim Crow and seeking better jobs, all contributed to the need for more public housing.

The city’s “Master Planner,” Robert Moses wanted massive “slum” clearance and urban renewal in his quest to rebuild much of New York. This part of Bedford Stuyvesant was the perfect place.

St. John’s athletic field was already empty of buildings. And the institution wanted to leave the neighborhood and relocate elsewhere. A deal was struck. The Home for Boys was sold for $400,000. A new “low-rent” — as they called it then — housing project would rise on the site.

The announcement was made by Robert Moses as early as 1947. The boys in the Home would be temporarily moved elsewhere, including downtown to St. Vincent’s Home, and would be reunited when their new facility was completed in Rockaway.

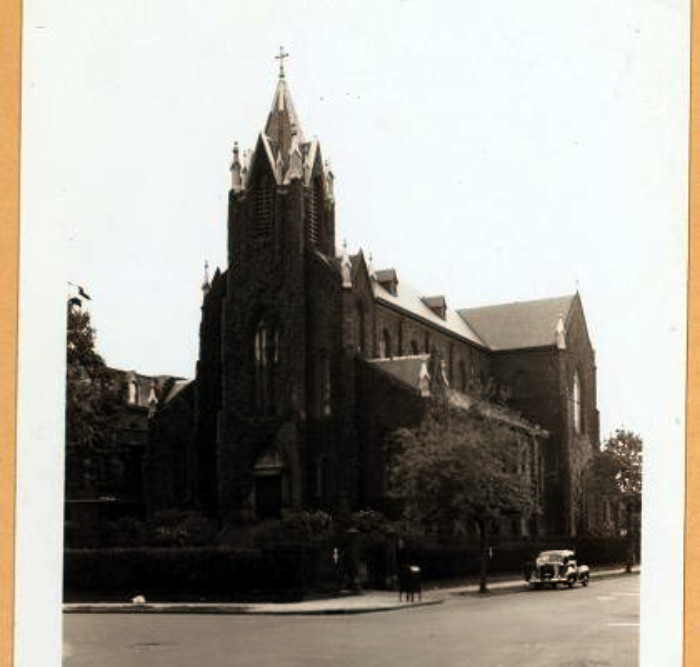

Chapel, 1940. New York Public Library

The last mass was held at St. John’s chapel on June 6, 1948. In attendance were the current residents of the home, as well as a crowd of former residents, some of them senior citizens.

The Home had a final gathering on June 16, 1948. Over 500 men and their families showed up. Men as old as 80 joined their fellows touring the grounds one last time, playing a game or two in the ball field. They had prayers and a bittersweet reunion with staff and friends.

Soon after, the wrecking ball destroyed the entire complex. On November 5, 1948, an official ground-breaking ceremony was held on the site. The Brooklyn Eagle captured the event. Robert Moses himself appears to the far right. He’s joined by elected officials and the head of the Housing Authority.

Ground Breaking, Brooklyn Eagle, 1948.

The Gowanus Houses, further downtown in Boerum Hill, had their groundbreaking on the same day.

The Albany Houses were designed by the architectural firm of Fellheimer, Wagner & Vollmer. They had similar projects under their belt, having built the Farragut Houses in 1942.

Housing models, Brooklyn Eagle, June 1948

Senior partner, Alfred T. Fellheimer had a long career, with several partners over the years. His first big project was Grand Central Terminal, in Manhattan, in 1904. But he also designed several other large train terminals, in Buffalo, Cincinnati and Utica.

In order to save money and time on their new low-rent development, the architects cribbed from other NYCHA plans, primarily from the Bronx River Houses. Loosely referencing the Bauhaus, they designed a 6-building complex of towers rising on a landscaped park area.

Albany Houses in progress, Brooklyn Eagle, 1949

The towers are all alike; pentagonal structures with five wings extending from a central core. The rooms in the apartments would all have light and windows, with all of the utilities and plumbing in the core. Only the bathrooms and kitchens would have common walls with their neighbors.

The Albany Houses were designed to have 824 apartments in four different sizes, housing 3,100 people. The smallest apartment had two rooms, the largest had four bedrooms. There were only 14 of the largest apartments.

Albany Houses, 1950. Museum of the City of New York

The Houses were supposed to open six months before they actually did, on Oct. 2, 1950. But inspections made after the walls were plastered showed shoddy workmanship, with bubbles, pits and craters all throughout the complex. Some walls had to be totally redone, and almost every wall had to be repaired.

More homes were then demolished to build a community recreation center and three more towers. Many of the people displaced by the expansion were selected to live in Phase 2 of the project. They had to wait until 1957, when the next three towers were all completed.

Albany Houses, 1950. Museum of the City of New York

Eight of the nine towers in the Albany Houses are 14 stories tall; the exception is 13 stories tall. Grass and trees were planted on the grounds, and parking lots, mandated by zoning, were built.

The people living in the towers were from all ethnicities and backgrounds. This was considered a “low-rent” complex. Originally, rents were no more than $30.50 a month for two rooms, up to $42 for five rooms.

Applicants for apartments, Brooklyn Eagle, 1949

From the very beginning, there were problems with local gangs terrorizing the women of the complex. The gangs of boys were not tenants, but came from the surrounding neighborhood. They snatched purses and knocked people down.

They rode the elevators and mugged mostly women who were running errands or going to work. There was at least one attempted rape. Children were afraid to go to the Children’s Museum, which was only two blocks away.

One representative of a for-rent furniture company, who had hundreds of clients in the complexes, was mugged in a stairwell, as he went floor to floor collecting rent. The tenants organized to demand more police protection.

But the police were loath to do much about it. They said they had to do a study to see if more patrols were needed. And so it began.

Albany Houses today, Google Maps

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment