Walkabout: A Parade of Champions, Part 1

Read Part 2 of this story. Landmarks aren’t always about great architecture. Sometimes they are great places, because important things happened there, or important people lived or gathered there. Today’s story is about one of those places, an unassuming house on a quiet block of Crown Heights North, called St. Johns Place. It’s a story…

Read Part 2 of this story.

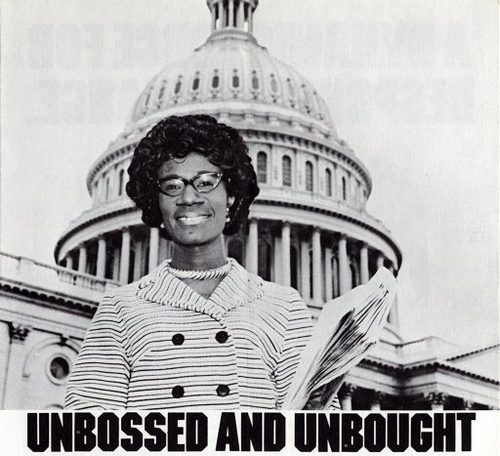

Landmarks aren’t always about great architecture. Sometimes they are great places, because important things happened there, or important people lived or gathered there. Today’s story is about one of those places, an unassuming house on a quiet block of Crown Heights North, called St. Johns Place. It’s a story of a house that is so steeped in cultural history that its legacy runs like a colorful rainbow down nearby Eastern Parkway every Labor Day. That culture is also two-fold, as this house was also once home to one of the most important African American women of the 20th century, Shirley Chisholm. Who would look at it, and think so much happened in this modest home, part of a row of equally modest homes? Ah, but looks can be deceiving.

This little corner of Crown Heights North, surrounding St. Gregory’s Catholic Church, is very interesting, historically, architecturally, and culturally. Architecturally, it represents the turn that residential design takes in the early 20th century, as two family and smaller, more suburban style homes are being built, rather than the grand row houses of only 20 years before. This neighborhood is home to the Kinkos double duplex homes, and rows of these modest, middle-class Tudor Revival bungalows.

1028 St. Johns Place is part of a small group of houses built in 1912. The houses are brick with steep peaked slate roofs punctuated by a single dormer. They are only 16.5’ wide, and 43’ long, with tidy little yards in front, and garages in the back, accessed by a service road. They were built only two years before St. Gregory’s itself was built, when the neighborhood was mostly second and third generation German, Jewish, and Irish.

Surrounding the house at this time were not the mansions of the rich, or even the long rowhouse streets of the upper middle class. This part of Crown Heights was known more for the hospitals, sanitariums, orphanages, old age homes, specialized schools, and other large charitable institutions that once filled this side of the St. Marks District.

Many of the homes in the neighborhood were probably filled with people who worked for these institutions; nurses, secretarial staff, cooks, clerks, medical staff and people filling any number of jobs. The subway came to Eastern Parkway in the first decades of the 20th century, and the area was convenient to trolleys, and of course, the ever-increasing number of cars, many of which were coming directly from dealerships on nearby Bedford Avenue. Ironically, the car would be the first signal of the change in the neighborhood itself.

African Americans began moving to central Brooklyn as early as the 1920’s and 1930’s, literally taking the A train from Harlem, or arriving on a boat from the Caribbean. Harlem’s prices and conditions were no longer favorable for many, especially those better off, and central Brooklyn’s homes were available to rent or buy. They continued to come. After World War II, suburban development and the promise of a new home under the GI Bill, enabled a large number of the white residents of the area the opportunity to leave the city for the suburbs of Long Island and Westchester, enticed by white-only subdivisions like Levittown, as well as the fear of minorities.

The 1950’s also saw a tremendous rise in immigration from the West Indies and Central and South America. The number of Caribbean immigrants to the United States rose from 36,000 in the 1940’s, to 472,000 in the 1960’s. The numbers would have been higher but for quotas set by the US for foreign immigration from certain areas. In the 1960’s, that law was changed, and quotas were abolished, leading up to a record number of 850,000 people emigrating from the Caribbean to the United States in the 1980’s.

By and large, the first wave of Caribbean immigrants from English speaking countries was educated, and motivated. Property ownership was a priority, and through pooling resources, or working long hours in multiple jobs, many became property owners in Bedford Stuyvesant, Clinton Hill, Crown Heights and Flatbush. To our story now come our players, two families from the West Indies, who would change New York forever.

In the early 1920’s, Shirley Chisholm’s parents arrived in New York from two separate islands, on two different boats. Her father, Charles Christopher St. Hill was originally from British Guiana (now Guyana), and her mother, Roby Seale, was from Barbados. Shirley St. Hill was born here in New York, on September 30, 1924. She was sent back to Barbados at the age of three by her mother, who wanted her to receive a proper British-style education. She returned at ten, well ahead of her peers in school.

Shirley went on to graduate from Girls High School, on Nostrand Avenue, and went on to Brooklyn College, and then Columbia, for her Master’s in education, which she received in 1952. Somewhere during this time, she lived in a house on Prospect Place, between Kingston and Albany, with her parents and sister. This block is now one of the “Superblocks,” the 1960’s urban renewal projects of the early Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation.

In 1949, she had married Jamaican-born Conrad Chisholm, and her post graduate career was in education and child care. In 1964, Shirley Chisholm ran for the NY State Legislature, and won. She was a member of the State Legislature from 1964 to 1968, when she ran for the US Congress. During her tenure as a State Representative, she and Conrad moved to a house at 28 Virginia Place, only blocks from Prospect Place. It is a stately corner house, built in 1899, and part of the Hampton-Virginia Place enclave of houses.

Ms Chisholm represented the 12th Congressional District from NY, and won her seat in 1968, the first African American woman to be elected to Congress. In 1972, she launched her historic bid for the presidency by running as a Democratic candidate seeking the party’s nomination. She campaigned seriously and well, while unflinchingly surviving three assassination attempts during the campaign. She won the Louisiana, Mississippi and New Jersey primaries and earned 152 delegates. The 1972 Democratic Convention would go on to nominate Hubert Humphrey, and Shirley Chisholm went back to Congress, the first woman, and first African American to make a serious run for the Presidency of the United States.

Soon after becoming a Congresswoman, the Chisholm’s bought 1028 St. Johns Place, and it was from this house that Shirley Chisholm planned her run for the presidency. Strategy meetings were held in the dining and living room of this small house. Her campaign drew in as many feminists as minority members, with Barbara Friedan and Gloria Steinem campaigning for her, even trying to become delegates for her at the convention.

Shirley Chisholm would remain in Congress until she retired in 1982, after serving seven terms. Her motto and rallying cry was that she was “unbought and unbossed,” and in her Congressional career she would oppose the draft and the Vietnam War, champion child care and education, and would sponsor a bill to provide minimum wages to domestic workers. For the latter, she sought the support of George Wallace, going to his hospital bed soon after he was shot, to the horror of her party members. He never forgot it, and gave her his support. The bill passed. This was typical Shirley, not about to let what other people thought interfere with the greater purpose.

Shirley and Conrad Chisholm divorced in 1977, she remarried in 1978, and her husband, Buffalo businessman Arthur Hardwicke Jr., died in 1986. After leaving Congress, Shirley Chisholm went back to education, her first love, and taught at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, and later at Spelman College in Atlanta. She campaigned for Jesse Jackson in 1990, and was appointed Ambassador to Jamaica by President Bill Clinton in 1993, but she never served, due to ill health. That year she was also elected to the National Women’s Hall of Fame. She retired to Florida, where she died in 2005. Shirley Chisholm is buried in Buffalo, NY, next to her husband, Arthur.

There was, of course, much more to her life in education and politics, and so much about Shirley Chisholm’s life in Crown Heights. She lived most of her life in Brooklyn within a ten block radius, in three different houses. The quiet little house on St. Johns Place must have been humming in 1972, when she dared to dream to be President of the United States of America. How did the neighborhood react to the newsworthy, and history making Mrs. Chisholm?

In 1973, Conrad and Shirley Chisholm sold their home at 1028 St. Johns Place. The buyer was a gregarious and charming machinist for the Transit Authority named Carlos Lezama. He paid $31,650 for the house, where he planned to live with his wife, Hilary, and their children. Carlos Lezama was originally from the nation of Trinidad and Tobago, two of the Leeward Islands, with Trinidad lying just off the coast of Venezuela, the southernmost of the West Indian islands. It is famous for the tintinnabulation of steel drums, the delicious taste of roti, and for the colorful costumed music and dance party that is Carnival. Carlos Lezama was a true Trini, and Carnival would be his legacy. His story, and the further story of 1028 St. Johns Place, will be told next time. GMAP

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment