Walkabout: Alms for the Poor, Part 2

Read Part 1 of this story. In my last post, I introduced you to the Kings County Almshouse, a 70 acre farm complex located in Flatbush. It was established in 1830, as Brooklyn’s population was swelling, and so too were the numbers of poor and indigent people who could not take care of themselves. Aside…

Read Part 1 of this story.

In my last post, I introduced you to the Kings County Almshouse, a 70 acre farm complex located in Flatbush. It was established in 1830, as Brooklyn’s population was swelling, and so too were the numbers of poor and indigent people who could not take care of themselves. Aside from people who were just out and out destitute and poor, the 19th century American almshouse was also designed to take in those who were mentally ill, developmentally slow or impaired, orphans, the blind, deaf and mute, and elderly people who had no families to take care of them.

The first two groups were generally called “lunatics” and “idiots”, and the understanding of their conditions was a long ways away. The understanding of the conditions of poverty was also long in coming, and arguably, we still haven’t figured out what to do with it, or the people affected by it. The Victorians knew, and acted accordingly. The world, after all, was simply filled with the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor. They attempted to help one group. The other one was on their own.

Many of our American social ideas come from our time of being an English colony. The British Isles have had a long history of social institutions that they felt would combat poverty. Prisons were high on this list, and in the case of those who could not pay their debts to their creditors, debtor’s prison was the sentence that was often imposed on entire families.

So were workhouses, where the poor could pay for their room and board by toiling in the many factories that represented the new Industrial Revolution. While we took on many aspects of British society, here in America, debtor’s prison was never popular here. Probably because a large percentage of Americans of British descent had come here as indentured servants and transported felons themselves, shipped to America from those very debtor’s prisons and penitentiaries of London and other cities.

But the social problems of an industrialized country were the same here as in England: what to do with the rising numbers of poor people, who were a drain on the normal levels of charity? The first idea was called “outdoor relief”. The county would auction off the care of the poor to the lowest bidder, who would take the poor person or family under their care, and having them work to earn their keep.

The county would help with small amounts of money, as well as fuel and other necessities. As one can imagine, this system, and the people in it, were ripe for abuse. A central institution giving care was then thought to be the answer.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, social policy towards the poor was centered on the almshouse, or poorhouse. This would continue in some fashion, until the New Deal. The idea was that a central institution, established on a county-wide level, would be the best and most efficient way to help the poor. Ironically, this system was based on the dual policy of both helping the poor and deterring them from asking for that help. Because tax dollars supported the county poorhouse, this also was seen as the answer to private charity.

Most counties throughout the country had a poorhouse. It was usually located far from the general population, and ideally had land around it suitable for farming, so that it could be self-sustaining, and generate income. Farm labor would come from the inmates, giving them the opportunity to help pay for their keep. Larger, and often more urban facilities might have small factories where inmates worked, as well.

The poorhouse was obligated to take everyone that society rejected, yet was seldom given enough resources to do so, especially as America grew in population, and it didn’t take long for these almshouses to be synonymous with hell. Although every child, even today, is told by their parents that they will be the cause of them going there, no one really wanted to go to the poorhouse. And for good reason, they were awful. This contradiction in terms caused any lofty goals in helping people to be mixed, at best.

On the one hand the counties wanted to deter people from asking for help, on the other hand, they were providing that humanitarian help. But almshouses were never able to be self-sustaining. They cost a lot to run, and the capacity of the inmates to pay for their own keep by working at the farm, or working at the almshouse itself, was greatly overestimated. There wasn’t enough staff, and facilities were not kept up. And the poor kept coming.

Remember the “deserving and undeserving poor?” The general societal outlook in the 19th century, and frankly, we still haven’t lost it, is that poverty was the fault of the poor. Helping the widows and orphans, the blind and old was one thing; they were the “deserving poor”. The “undeserving poor,” were another story. It was thought that institutionalizing the poor would rehabilitate them, and train them to be productive citizens.

Their incarceration would teach them discipline, which was obviously all that was lacking and the reason for their poverty in the first place. To this end, once in the poorhouse, children were separated from their parents and put in separate orphanages or sent away, husbands and wives were segregated into workhouses, and not allowed to even speak to each other, and conditions could be so awful that some would rather starve in the street than go to the almshouse. Irish and Negro families were especially targeted for separation and incarceration, as both groups were seen by many in the upper classes to be at the bottom of the social order, and responsible for their own conditions.

In 1857, the Kings County Almshouse in Flatbush, housed 380 people. The almshouse nursery had 350 babies and children, while the hospital was caring for 430 patients, and the attached lunatic asylum had a population of 205. In total, there were 674 males, 691 females, of which 870 were foreign born, 475 native born, including 424 children under sixteen years of age. All of these people were under the care of only one keeper, aided by three male and four female assistants. The sexes were kept completely separated from each other at all times.

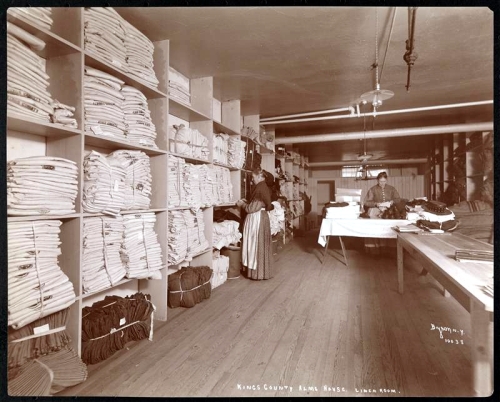

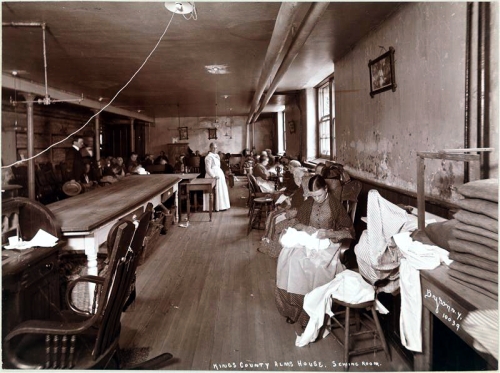

Everyone there was required to work, either on the farm, or on the complex. Children over twelve were bound out by the superintendent, and could be “rented out” to factories or other facilities. Elderly inmates were not exempt, either, unless too infirm to do chores or factory work.

The 1857 report that details the conditions and population of the Kings County Almshouse goes on to admit that the place was overcrowded and understaffed. Yet, as justification of conditions, the report on the facility states that two-thirds of the inmates were forced to accept this public charity because of inebriation, which seems hardly likely, due to the numbers of children and inmates of the insane asylum, alone.

The inmates of the asylum were in especially horrible conditions. The insane were seen by many to be just a burden on society, as well as a danger. At Kings County, they were incarcerated in a separate facility, and either allowed to wander around uncared for, or were placed in various kinds of restraints. There were more women than men here. The facility was designed to hold 150 patients, but in 1857, had a population of 205. As horrible as conditions here were, this report also noted that the asylum was now under a new administration. The previous one had abused the patients, resulted in permanent crippling of several, and obvious marks of chains and confinement on others. The report was happy to state that this was no longer the case.

The Civil War actually began the change in poorhouse policies. As the above report from Kings County and other poorhouse records began to show, the poorhouse model was not working. Almshouses were expensive to run, were not self-sustaining, as designed, and the numbers of the poor were overwhelming the facilities. It was becoming obvious that laziness and drunkenness were not the only contributing factors to poverty, and as deserving or undeserving as the poor may be, there were far too many to manage by incarcerating them in poorhouses.

On top of that, the war produced widows and orphans, parents, grandparents and children without the male breadwinner, and a great deal of temporary and permanently disabled men who were not able to work. Yet very few of these families were put into poorhouses, because the government began to take a hand, establishing pension plans for veterans, and temporary aid to veterans and families by means of direct “outdoor relief”; in the form of monetary payments. Governmental social services had begun.

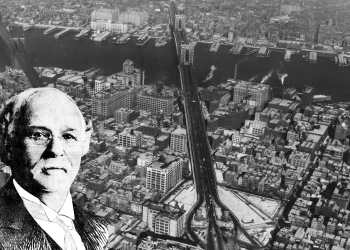

Poorhouses continued into the 20th century, but were changing. By the turn of that century, many large poorhouse facilities had divided into their separate parts. The Kings County Almshouse also changed. Although it operated into the early 20th century, the hospital part of the complex became the nucleus of present day Kings County Hospital. The rest of the buildings were eventually torn down in the 1930’s to expand the hospital, today a huge complex.

The almshouses got out of the mental health field, and separate facilities, generally known as insane asylums, were built, usually as far away from everyone else as possible. Mental health care has a long way to go. Separate orphanages became more expedient for children, which has changed into in-home foster care, and most almshouses became homes for the growing number of senior citizens who could no longer take care of themselves, or had anyone who would take them in.

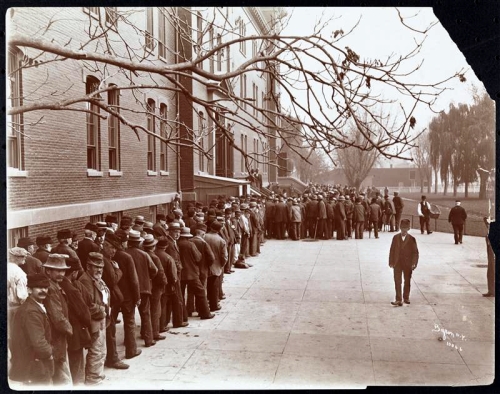

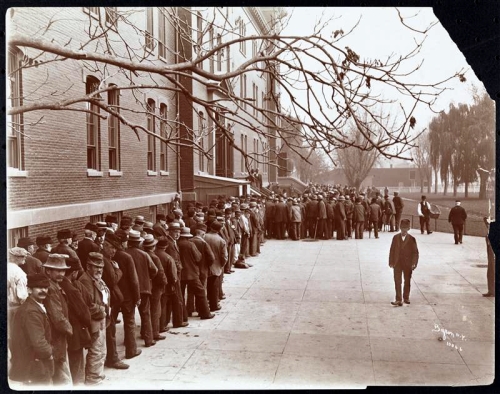

By the beginning of the 20th century, almshouses were old age homes. The Museum of the City of New York has a series of fascinating photos of the Kings County Almshouse taken in 1900. The majority of the inmates are elderly. (Link not functioning. Go to MCNY site and enter Kings Country Almshouse.)

Governmental aid to the poor and elderly changed as well. Social security was established in the New Deal era of 1935, during the Great Depression. Workman’s compensation, unemployment compensation, welfare, and other social safety net programs would follow. By the 1950’s, the last of the poorhouses had closed. The institutions may have closed, but the challenges and resources to deal with the root causes remains. Poverty remains one of society’s largest, most complicated, and most contentious problems. Alms for the poor, unfortunately, are needed more than ever.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment