Walkabout: Brooklyn and the Fight for Freedom

Read Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4 of this story. Brooklyn was home to one of the largest concentrations of anti-slavery activists in the entire United States. Decades before the Civil War, Brooklynites not only fought the good fight against slavery, but they were the leaders in many of the metropolitan area’s many organizations…

Lewis Tappan’s house at 86 Pierrepont Street. Photo by Nicholas Strini for PropertyShark

Read Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4 of this story.

Brooklyn was home to one of the largest concentrations of anti-slavery activists in the entire United States. Decades before the Civil War, Brooklynites not only fought the good fight against slavery, but they were the leaders in many of the metropolitan area’s many organizations and causes. This was both ironic and just, as Kings County had also been home to the largest number of slaveholding citizens in the North. New York State was the last of the Northern states to abolish slavery, in 1827, long after most of the rest of the North had abandoned the institution.

Slavery just didn’t sit well with the industrialized North, and made little sense, economically or morally. But New York City? Well, that was a different story. It wasn’t that slaves were needed in the city itself, or that state, for that matter. It was, as it always is in New York, about money. Many of the city’s wealthiest and most powerful financiers, merchants, commodities traders and shipping magnates made a ton of money from slavery. They were the bankers to the plantations, the markets for the cotton, tobacco and other crops, and they shipped the goods from Southern ports to destinations in New York, Brooklyn and all over the world. If slavery ended, so did their massive profits and their way of life. It wasn’t personal, it was business.

In the decades after the Revolutionary War, the anti-slavery movement gained ground in New York City and Brooklyn. Many different abolitionist societies were formed, and some of them counted as members some of the most influential men and women in both cities. But in the massive disconnect that the institution of slavery produced, some of these men belonged to the Abolitionist societies while still having slaves, and others joined while still supporting their plantation and slave-owning clients in the South. Some of them had the grace to see the dichotomy, others did not.

Finally, in 1827, New York abolished slavery within its borders. Lawmakers and business interests had placed a large number of conditions on the manumission of slaves up until that point, but that was all over now. All of New York’s slaves were now, and forever free. There was great celebration in the black communities all over the city, and in many white communities, as well. As soon as the celebrations stopped, the work to abolish slavery everywhere in the United States took on a new urgency. If all of the slaves in the United States were not free, could anyone of color feel safe to live his or her own life, knowing that there but for the grace of God, and geography, went they?

Most of us are aware of the great leaders of the anti-slavery movement who lived in Brooklyn. The most well-known is Henry Ward Beecher, the firebrand preacher of Pilgrim Congregational Church in Brooklyn Heights. He may have been the most famous, but he was but one of a great many of Brooklyn’s abolitionist leaders. Many of those leaders were themselves African American.

Black people in Brooklyn in the mid-19th century had a two-fold mission. The first was to establish themselves as equal citizens of Brooklyn and the United States; equal in opportunity, work and commerce, education, social opportunities and citizenship. This was quite difficult in a town that refused to educate Negro children in its public schools, or hire blacks for jobs beyond their “station.” In spite of that inequality, Brooklyn’s black population was also dedicated to working for the end of enslavement for millions of men, women and children who toiled in endless slavery, the masters and mistresses of nothing.

Although they shared many of the same goals, Brooklyn’s white and black abolitionists did not interact all that much with each other. They still lived in separate worlds, and had very different expectations and goals. There were exceptions to this, of course, and as the anti-slavery movement grew in power and influence, all of the leaders found themselves in physical danger, as well.

Two of the most influential of Brooklyn’s white anti-slavery activists were the Tappan brothers. Arthur and Lewis Tappan were millionaire merchants, living in Manhattan in the early 1830s. Both were also very religious men. To a large extent, Lewis’ religious convictions were shaped by his attendance in the church of Lyman Beecher, Henry Ward Beecher’s father, whose religious philosophies also shaped his son. He came to NYC from Massachusetts with a zeal for social justice, and a firm commitment to Christian principles.

Once in NYC, Lewis joined Arthur’s business, and both were hugely successful. They supported religious organizations such as the American Bible Society and the American Education Society, but soon became caught up in the Anti-slavery movement. Both brother were highly offended by slavery, as well as by the mistreatment of blacks in general, and put their time and money into action.

Lewis and Arthur Tappan were among the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society, one of the most important of the many abolitionist organizations in the United States, founded in 1833. They supported the publication of anti-slavery journals, and helped found Oberlin College, in Ohio, which admitted black students equally with white, male and female. They also supported the crew of the Amistad during their trial in Brooklyn.

The Amistad was the Spanish slave ship that was on its way to deliver new captives into slavery, when those captives took over the ship, which landed in New Haven. Some wanted the former captives returned as “property”; others wanted them to be welcomed into the United States, while others wanted them to be sent back to Africa. That’s a tale for another day, but the Tappan’s were instrumental in getting food, clothing and aid to those on the ship, as it lay in the harbor while the authorities tried to decide their fate. They also arranged for top legal representation, and paid for the eventual reparation of the former captives, back to Africa. In doing so, they met with other white and black abolitionists who lived in Brooklyn.

In 1834, Lewis Tappan opened up the chapel next to his home on Chatham Street, for the annual celebration of Emancipation Day, where New York’s African Americans celebrated the end of slavery in New York. A large group of black and white celebrants gathered at the chapel, which was one of the few mixed congregations in the city, and Tappan read aloud the “Declaration of Sentiments,” the mission statement of the Anti-Slavery Society. That year, a group of pro-slavery white demonstrators crashed the party, and then began trashing the chapel and fighting with the celebrants, sparking a riot that lasted for several days. At the end of it, Tappan’s chapel and home were in ruins, his furniture and possessions taken out and burned, so he, his wife and children moved to Brooklyn Heights.

Six years after founding the American Anti-Slavery Society, the Tappan’s brought a branch to Brooklyn, called the Brooklyn Anti-Slavery Society. The officers and core members of the group all lived in Brooklyn Heights or Cobble Hill. They were all merchants, plus one lawyer, and there were no blacks in their organization. They were also all men. Their wives formed their own societies, with similar goals, but with a different focus, often mixing abolition with general women’s rights. The tales of babies torn from slave mothers’ arms, and the cruelty of men, especially towards women, made these ladies especially fierce opponents to slavery, sometimes even more so than their male counterparts.

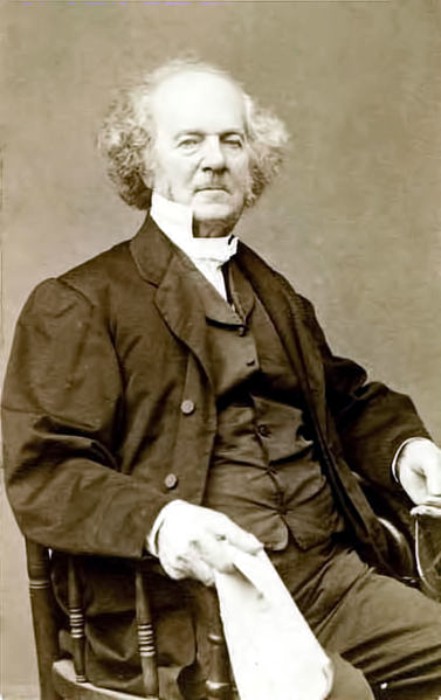

Lewis Tappan lived at 86 Pierrepont Street, a house that is still standing, albeit with great alterations. He and his first wife Susannah moved there after the riots, and Lewis Tappan lived there for the rest of his life. Their daughters were both active in anti-slavery organizations, and became leaders in the women’s abolitionists movement. Susannah died in 1853, and he married his second wife, Sarah, a year later. She was also a staunch abolitionist and participated in anti-slavery organizations. The Tappan’s worshipped at Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Church. Both Tappan brothers lived to see slavery end. Arthur died in 1865 in New Haven, Ct. while Lewis died in Brooklyn in 1873.

Lewis had some views that alienated him from many of the white abolitionists he worked with. He believed that intermarriage between the races was the only long term solution to racism. Only when everyone was the same would hatred cease. He was an “immediatist,” who didn’t want slavery to phase out, but be ended immediately. This ruffled the feathers of those who were still profiting from the labor of Southern slavery. After the Civil War, he donated generously to schools, black colleges, and mission societies that sought to educate blacks, and advance the race in American society, but he didn’t think there would ever be equality, unless is was taken, not asked for. In many ways, he was far ahead of his time, although he didn’t believe in women’s rights.

While the very rich and influential, like Lewis Tappan, could be an organizational and financial boon to any movement, most of the black people involved in the fight for abolishing slavery had far less money and influence in the greater community. Brooklyn’s black population was extremely active in the anti-slavery movement, but in an entirely different manner. The 1830s were a frustrating time for the activists. Slavery was going strong, and all the talking and activism seemed to be going nowhere. They were just preaching to the choir. Meanwhile, the enslaved were beginning to put their feet on the road, and were escaping north with a regularity that disturbed Southern officials.

People like Frederick Douglass were not only escaping north, they were turning around and becoming the slaveholder’s worst nightmare: eloquent and intelligent survivors who were telling their stories and galvanizing the movement in the North. Slave catchers began flooding Northern cities, looking to re-capture escapees. Very often they would just snatch people up off the street, including blacks who had never been slaves, and whisk them down South and into slavery, often gone forever. Many Northern lawmakers did not concern themselves to stop them.

The Abolitionist Movement had to change, and become pro-active. It was called “practical abolitionism,” and it meant getting in the faces of the oppressors, and sometimes physically defending yourself and others. The greatest of these practical abolitionists was a studious looking black man named David Ruggles. His story is next.

David Ruggles, the Tappan brothers, and many of Brooklyn’s known and unknown valiant anti-slavery warriors are part of a ground breaking project called In Pursuit of Freedom: Anti-Slavery Activism and the Culture of Abolitionism in Antebellum Brooklyn. The project was a joint effort of the Brooklyn Historical Society, the Weeksville Heritage Center and the Irondale Theater Ensemble, and represents years of research and investigation into this little known area of American History. There’s a website connected to the project, as well as exhibits and a theatrical production.

Read Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4 of this story.

People in Brooklyn — and indeed across the country — should celebrate the effort of Brownstoner to tell the story of the Brooklyn abolitionists, both black and white people. Almost 150 years ago, they helped bring about the emancipation of enslaved people and the ratification of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the US Constitution.

It is appropriate that the first of a series of articles features Lewis Tappan. He led the committee that financed the defense of the Africans captured on the Schooner Amistad through the successful argument of their case in the United States Supreme Court in 1841.

Tappan’s story is continued in my new book about anti-slavery activities at Plymouth Church before and during the Civil War and through Reconstruction. (Entitled Brooklyn’s Plymouth Church in the Civil War Era: A Ministry of Freedom, published by The History Press in September authored by me, assisted by Lois Rosebrooks, the Director of History Ministry Services at Plymouth Church.) The years covered by the book are from the founding of the church in 1847 through the ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870. The book tells the story of the minister, Henry Ward Beecher, working together with his congregation, including a dozen main characters and another dozen “friends of the church,” both black and white people, who worked with the congregation in the abolitionist movement.

Briefly stated, Tappan was a member of the Plymouth community from its founding by 21 people, including his daughter Lucy and son-in-law Henry Chandler Bowen. Through them, he worked with Henry Ward Beecher, introducing Beecher to the New York abolitionists who were leading the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and holding meetings of the American Missionary Association at Plymouth Church. Plymouth Church member George Whipple and Tappan were leaders at the missionary association and directed the remarkable relief and education project for freed people in the South during the Civil War. When Tappan retired in 1865 at the age of 77, Whipple continued their work until his death in 1876, leading the association in founding eight colleges and universities in the South and founding the theological department of Howard University.

I applaud the efforts of Brownstoner to tell these stories and look forward to the next installment.

Frank Decker