Walkabout: Brooklyn’s Amazing Automobile Industry, Part 1

“As Brooklyn goes, so goes the world,” Charles Bishop told the Brooklyn Eagle in 1941. He was referring to the automobile industry in Brooklyn, a world he knew as well as anyone, being one of the pioneers in the industry that once dominated the core of the city along Bedford Avenue in Central Brooklyn. In…

“As Brooklyn goes, so goes the world,” Charles Bishop told the Brooklyn Eagle in 1941. He was referring to the automobile industry in Brooklyn, a world he knew as well as anyone, being one of the pioneers in the industry that once dominated the core of the city along Bedford Avenue in Central Brooklyn. In the space of forty years, approximately between 1905 and 1945, the automobile industry took over Bedford Avenue and its environs, creating one of the most lucrative and far-reaching areas of business, the likes of which we will never see again.

It all begins with the road and the wheel. The road was Bedford Avenue, the main north-south roadway in Brooklyn, stretching the length of the city, a vital thoroughfare connecting the towns that make up the city of Brooklyn, running from Greenpoint, south to Sheepshead Bay. By the end of the 19th century, Bedford Avenue, between Grant Square in Bedford, and Williamsburg, was one of the busiest and most important streets in the city. There were blocks with fine homes, especially in Williamsburg and central Bedford, but it was also filled with large houses of worship, clubs, theaters, schools, restaurants and businesses. The street was connected by trolleys and omnibuses, and the Long Island Railroad stopped at Bedford, near Fulton and Atlantic, but in the mid-1880s, a new mode of transportation had also taken to the streets. No, not the car, I’m talking about the bicycle.

For a more complete look at the popularity of the bicycle in Brooklyn, during the end of the 1800s, please read the two Walkabout articles listed below. It’s like déjà vu all over again, for Brooklyn and the bike today. The bike took over Brooklyn, especially Bedford Avenue, which was a popular street for bike excursions, for the same reason it was a popular street for any kind of traffic. Bicycle stores began to pop up along the route, followed by bike repair shops and clothing stores catering to riding apparel. Restaurants followed suite, and inevitably, so did bicycle clubs. These clubs were popular to all segments of the population, with clubs founded by neighborhood, race, religion and ethnicity, and income. Most of the clubs were for men, but women also found bicycling to be a healthy and for the most part, socially acceptable sport.

The Bedford section of Brooklyn, the central part of what is now Bedford Stuyvesant and northern Crown Heights became home to many of the clubs, especially the one of the largest, richest and most famous, the Kings County Wheelmen. Their expansive headquarters was a four story building next door to the Union League Club, in Grant Square, on Rogers Avenue, between Dean and Bergen Street. As popular as the bicycle was, it was soon to be eclipsed by even better wheels: the automobile.

In telling the history of Automobile Row, Charles Bishop gives a Dr. John B. Zabriskie credit as being the first Brooklynite to own a car, a steam powered Winton automobile he purchased sometime in the 1890s. He also said that the first auto showroom in Brooklyn was on Fulton Street, between Bedford and Nostrand; a Haynes Automobile Company dealership, which opened in 1893, called Perkins, Adams and Hawkins Automobiles. It was soon followed in 1898 by a man named King, who had a showroom on Union Street, near Prospect Park, and in the same year, A.G. Southworth took up a dealership for Waverly Electric cars as an adjunct to his bicycle business. His showroom was on Flatbush Avenue, and he soon gave up bikes, and took on Toledo Steam Cars, followed by Nash Ramblers. The car business was on.

Bedford Avenue’s first showroom opened in 1899, when John Mears opened a dealership for Studebaker and U.S. Long Distance cars. It must not have suited him all that well, because he wasn’t in business very long before he sold out the I.S. Remsen Carriage Company, which had been making and selling horse drawn buggies. Remsen, a familiar Brooklyn name, turned the automobile part of his business over to another old Brooklyn family man, William Kouwenhoven, who managed the business for many years. Eventually, Remsen found his carriage business to be more successful, and he got out of the car business, and Kouwenhoven ended up working for Charles Bishop.

Charles Bishop’s father, Eli, was one of the pioneers of Automobile Row. In 1905, this English immigrant founded a dealership on the corner of Halsey Street and Bedford Avenue, selling cars made by the Dodge Brothers Automobile Company. Bishop already was a rich man, having made a tidy fortune as a real estate developer and builder, with a large swath of nearby Bedford to his credit. After having helped build up the upscale community of Bedford, what better occupation to then sell the people in those houses something Brooklynites would soon find they really wanted – a shiny new automobile, the status symbol of the 20th century.

Bishop’s Dodge dealership, as well as the Mears/Remsen Studebaker dealership, was soon joined by others. Seemingly overnight, the corridor of Bedford Avenue, between Grant Square and Gates Avenue was teeming with auto related businesses. Automobile Row was born. Car dealerships abounded, as well as garages, auto parts suppliers, and service stations. When Bedford ran out of room, the businesses began to spread out along Fulton Street, Atlantic Avenue, and as the “aughts” turned into the ‘teens and 1920s, automobile related businesses began to spread south far past Grant Square, along Bedford, sometimes Rogers, Franklin and Classon, on down to first Eastern Parkway, then Empire Boulevard.

This was possible because there was available and relatively cheap land for sale, especially the further south you went. It was also popular because it was easy for people to get there by public transportation. Many of the bicycle shops had turned into auto related shops, so established businesses were already in place. Bedford Avenue was a promenade street, home to leisurely strolls up to Grant Square and its upscale blocks in what was being called the St. Marks District. It was also a popular parade route, with two armories along the route, and Grant Square itself, a popular place for political rallies and patriotic gatherings under the statue of Ulysses S. Grant.

The term “Automobile Row” began appearing in the press by the ‘teens, and was seized by the industry. Manhattan had a famous Automobile Row too; it was Broadway, in the 50’s, up to Columbus Circle. Brooklyn was not going to be overshadowed again by Manhattan. With much more room to work with, Brooklyn’s Automobile Row soon overshadowed Manhattan’s in the length and scope of its dealerships and businesses. By 1912, there were 25 car dealerships in the area alone, plus auxiliary businesses. And nothing helped establish the Row more than the car show.

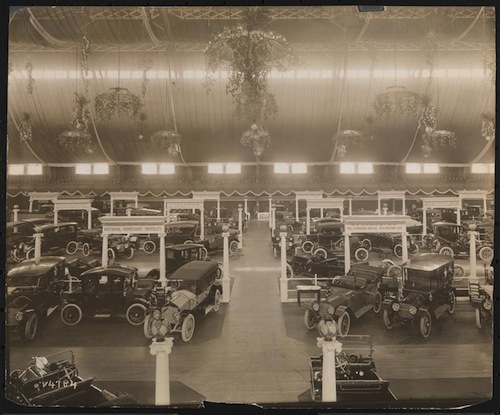

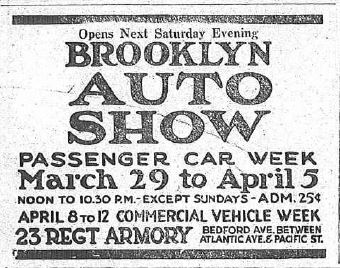

The automobile trade show still draws thousands of people to see the cars of the future and the present. For the price of admission, anyone can come and look at the latest models the car companies have come up with. If you can afford it, the shows are a one stop shopping experience. If you can only look and dream, the auto show allows that dream to be reality, if only to allow a touch for a moment. All of the industries innovations, new makes and models, as well as accessories, are on display, and it is a time for the car companies to shine. Manhattan may have had its Coliseum, but Brooklyn had the 23d Regiment Armory. From 1911 until World War II, the armory was the bi-annual place to be for Brooklyn’s growing automobile industry.

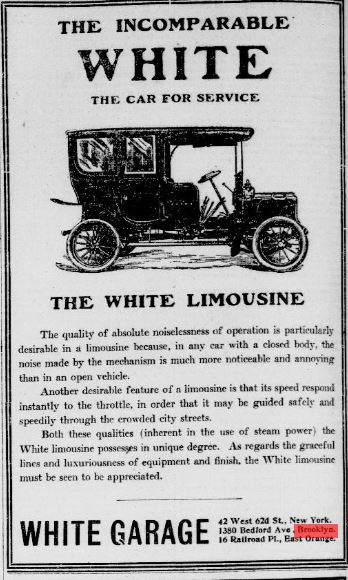

The Brooklyn Auto Show was one of, if not the top, auto show in the entire country. Before the Big Three automakers took over the American industry, over fifty different companies showed their wares at the armory show. The armory was huge, offering plenty of room for the dealers and manufacturers to display their products. They were joined by tire makers, and manufacturers of brakes, horns, accessories and motoring wear. There were high standards at work here, as auto manufacturers seemed to be popping up as fast as weeds. The armory would not allow a company to display their wares in the show if they didn’t have a proven reputation and track record for quality. This was one reason why the show was so popular. Most people didn’t really know anything about cars, but trusted that a car maker, or even a horn maker, had been vetted, and had a quality product for sale.

So who were these auto makers? There were dozens of them represented on Automobile Row, most of which we have never even heard of, unless you are an antique car aficionado. We’ve all seen and heard about Studebaker, Packard, Dodge, Cadillac, Chrysler and Ford. But what about the Cino, the Marmon, the Haupt, Overland, White, Apperson or the Locomobile? We’ll talk about all of them, and conclude the rise and fall of Automobile Row, next time.

(1913 Auto show at the 23rd Regiment Armory. Photo: Museum of the City of New York)

Knights of the Knickerbocker, Part One (a history of Brooklyn biking)

Knights of the Knickerbocker, Part Two

I’m leading a tour of Bedford Avenue’s Automobile Row this Sunday, at 11 am. I’ll be joined by my tour partner Morgan Munsey, and we’ll be visiting the areas discussed here and on Thursday. The tour is sponsored by the Municipal Arts Society, and they still have tickets available. Please visit their Website, and we hope you’ll join us.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment